Sign up for The Media Today, CJR’s daily newsletter.

Veteran Venezuelan reporter Elyangélica González’s 20-year career in journalism came to an inflection point in late March, when covering her country’s ongoing crisis unexpectedly turned her into the story. González, a reporter for Univision and Colombia’s Caracol Radio, was covering a protest in Caracas where thousands of students had gathered in front of the Supreme Court, calling on the government to respect the constitution. The National Guard began pushing the students away, and a group of pro-government civilians, known as colectivos armados, started attacking the students.

At that point, González received a call from her radio station asking her to go live on her cell phone to cover the attacks on the students. A female National Guard officer overheard González reporting and started screaming at her to leave.

RELATED: NYT reporter on getting barred from Venezuela amid chaos

What happened next was captured on a video that quickly went viral across Latin America. The footage not only showed a fearful González being surrounded and manhandled by the Venezuelan military simply for trying to do her job, it revealed the dangerous escalation of violence against Venezuelan press covering weekly (sometimes daily) mass protests that have left more than 100 people dead in a country teetering on the brink. The situation has gotten so dire that the Committee to Protect Journalists published a special report for Venezuela with a comprehensive list of specific threats and precautions for media covering the disintegrating state.

The recent rise in attacks on local and foreign press is an ominous sign. According to the National Press Workers Union, in the first four months of this year, there were more than 200 attacks on journalists in Venezuela. And that doesn’t even include the four journalists recently detained and arrested, and several other journalists who were attacked during the controversial installment of the National Constituent Assembly on July 30.

“I explained that I had press credentials, and that I was on air, but another officer came and ripped the phone from my hands,” González recalls. “The female officer grabbed me by my hair, knocked me to the ground, and began kicking me repeatedly.”

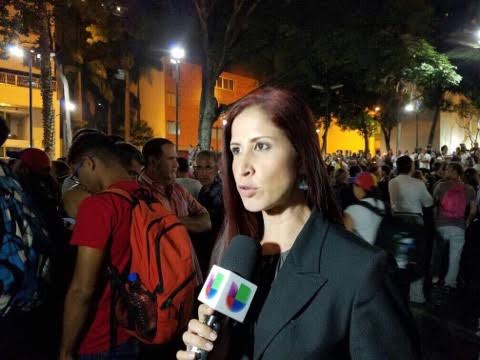

Reporter Elyangélica González covers a vigil organized by students after a protester was killed in March 2017, at Plaza Bolivar de Cachao, Caracas. Courtesy photo.

Another officer approached and whispered, “This is what you wanted,” González says. Then, at least 12 other guards arrived. They grabbed her and violently dragged her on the ground several feet from where she had been standing, hitting her and pulling her by the hair, and then threw her down again. She was briefly detained, and before they released her, one of the female officers threw her phone at her and screamed, “Here’s your phone, whore.”

If the physical attacks and threats weren’t enough, González says the government has also waged a propaganda war against the media, repeatedly discrediting their work and encouraging violence against journalists by citizens who support the government. The foreign press is routinely referred to by Venezuelan officials as “media scoundrels” and “fake internationals,” which may sound familiar to reporters working under the Trump administration.

Many international TV stations in Venezuela, like Argentina’s Todo Noticias, Colombia’s El Tiempo, and CNN have been banned or had their broadcast signals blocked under President Nicolas Maduro’s reign. A New York Times reporter was blocked last year from reentering the country. Private Venezuelan TV stations ceased any critical reporting on the government years ago, and a slew of radio stations and websites that once challenged government policies were shuttered by the National Telecommunication Commission.

According to González, President Hugo Chávez started the war on the media, and it escalated rapidly under President Nicolás Maduro.

“Controlling communications was a priority for Chavez’s government,” González says. “What’s different now is that all these control methods have been radicalized, regularly changing facts in their favor, and converting victims into aggressors.”

ICYMI: “I don’t tweet. I don’t care.”

And while some of the Venezuelan press corps is fighting back, battling censorship in creative ways like holding up cardboard TV cutouts on buses to provide uncensored news to wary travelers, others have chosen to leave. The exiles now practice their journalism independently, amassing massive social media followings to inform fellow countrymen from abroad, hoping to still have some impact. Carla Angola, now living in Miami, and Maibort Petit, now living in New York, are two such journalists thriving outside the country’s borders.

The day after González was attacked while reporting live on air, she started to get anonymous phone calls. “Why haven’t you taken the girls to school yet?” a soft male voice inquired on the other end of line. She felt a streak of terrible panic, and immediately hung up. The anonymous caller rang again and again. The calls came at least five times a day. For a while, González stopped answering.

Then, one day, she received a call in late June from her daughters’ school saying that someone was looking for her children to pick them up.

“I went immediately to the school to speak to the principal to tell her that I had not authorized anyone to take the girls,” González says. “I asked her to be vigilant about this. Coming into the school, I got another one of those calls. I remember it exactly: ‘We are near Sofia and Camilla. Next time, we take them.’ I panicked.”

She called her husband and told him she did not want to test whether these threats would materialize. They had to leave.

González covers another protest. Courtesy photo.

“If my vocal cords get torn out, I will write,” González says. “If paper is taken away from me, I will do hand signals; and if stopped, I’ll send smoke signals. Shutting up isn’t an option for me.”

González would rather not say where she is these days, fearing for the safety of her family. The radio network she collaborates with, Caracol, just gave her a weekly news show, Venezuela Without Borders, to continue covering what’s happening back home.

Since leaving Venezuela, she’s had time to reflect on what happened. Amid all the difficulties of moving somewhere new, the one saving grace is her daughters’ happiness. They can play freely now. “My circumstances sometimes make me feel irascible or drive me to tears,” González laments. “And my country’s condition—which I follow every minute—isn’t helping at all.”

But, she says, she vehemently believes in the Venezuelan people and their capacity to overcome this situation.

“Maybe it’s a romantic idea, but I think that people want to live in that prosperous Venezuela, a country that once had guarantees, democracy, and development,” González says. “I want to tell that story of Venezuela’s return.”

ICYMI: After North Korea threats, Twitter turns to dark humor

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.