Sign up for the daily CJR newsletter.

Earlier this week, the Nicolás Maduro regime detained and expelled journalist Jorge Ramos, one of the most famous news anchors in the world, along with the rest of his crew because Maduro didn’t like the questions Ramos was asking. If a journalist as well-known as Ramos and a network as large as Univision can be expelled from the country, what will be the fate of the local press in Venezuela?

The Chávez and Maduro regimes have managed to eliminate most of Venezuela’s independent media by shutting it down, imposing censorship, blocking their digital presence, or having government sympathizers acquire the media companies.

At least 60 private media outlets have closed since the rise to power of Chavismo in Venezuela, according to the Venezuelan union of journalists (SNTP in Spanish). In 2007, Hugo Chávez shut down Radio Caracas Televisión, one of the most important TV networks in the country, replacing it with TVes, which is managed by Winston Vallenilla, a friend of the regime.

In 2009, 34 independent radio stations across the country lost their broadcast licenses and were forced to end their transmissions due to “legal procedures” established by CONATEL, the equivalent of the FCC in Venezuela. This was just the beginning.

Channel 8, previously a public broadcasting service, is now VTV, the official network of government propaganda. The newspaper El Universal, which was owned by the Mata family for generations, was acquired by an opaque Spain-based company called Epalisticia. Últimas Noticias, the newspaper with the largest circulation in Venezuela, was said to be sold to an English company, but its real owner is unknown and the people who manage its day-to-day operations are close to the Maduro government. Miguel Ángel Capriles López, who used to own Últimas Noticias as well as a sports and a business newspaper, now lives in Spain. Globovisión, a fierce critic of the regime previously owned by the Zuloaga family, was bought by Raul Gorrin and Gustavo Perdomo in 2013. Gorrin has been under investigation by the Department of Justice for corruption and money laundering. All of these outlets changed their editorial line in favor of the regime after the buyouts.

The Camero family, which owns the TV network Televen, has tried unsuccessfully to sell the channel. As a result, they exercise a healthy dose of self-censorship. Venevisión, the most highly rated channel in the country, does its best to appear impartial, but no doubt engages in self-censorship as well.

All this censorship has spawned a diverse digital ecosystem. New independent voices have emerged, combining the expertise of veterans such as Nelson Bocaranda Sardi with a younger generation of journalists.

But digital players like El Pitazo, Runrunes, Armando.Info, and LaPatilla.com have been selectively targeted by the government with hacks, as well as blocked by CANTV, Venezuela’s state-run phone and internet service provider.

The judicial system has become complicit in this state policy against the media. Most recently, four journalists from Armando.info’s team were forced into exile. After they published an investigative report about corruption by a friend of the Chavista regime, they were subject of a private libel lawsuit and judicial persecution by the state. They now manage the site from abroad.

What hasn’t been shut down or forced to sell by the government has been severely hit by the economic recession. In December, El Nacional, Venezuela’s last national anti-government newspaper, published its final print edition after years of functioning with a skeleton crew and dwindling resources. The business of importing newsprint paper is also controlled by the chavista government, an additional strategy for censorship. At least 40 regional and local newspapers have shut down because of lack of newsprint.

But Maduro’s regime hasn’t limited itself to the targeting of local media; it has censured the foreign press as well. The German journalist Billy Six has been held in custody by the Venezuelan government since November 2018 without access to a lawyer or any contact with family members or anyone else. He is held in a prison cell without any daylight. On February 25, he went on a hunger strike to draw attention to his case.

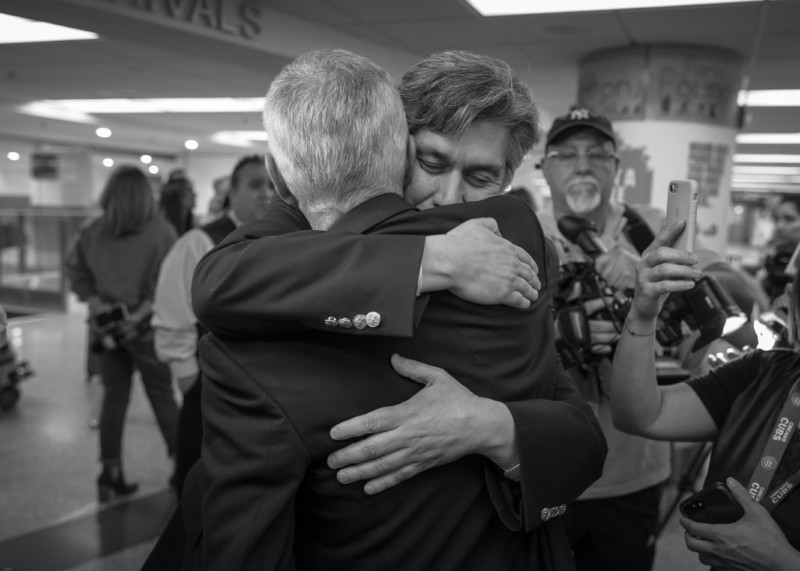

As for the Univision team, thankfully they were eventually released, though they were expelled from the country. They brought two of Univision’s local Venezuelan journalists back with them because they no longer felt safe. I used to be president of news at Univision, and I worked closely with Ramos for eight years. It warmed my heart to see my former colleagues, led by my successor Daniel Coronell, give him a hero’s welcome when he returned to the newsroom. It was inspiring to see people celebrating those who are willing to ask the uncomfortable questions that others are afraid to ask.

Venezuela is in crisis. This is a dire moment, and a free press is more important than ever.

ICYMI: Reuters publishes ethically questionable story

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.