Sign up for The Media Today, CJR’s daily newsletter.

Over a 40-year career at The Miami Herald, Tim Chapman covered more than 50 hurricanes, rolled up on thousands of crime scenes and parachuted, figuratively speaking, into wars and coups around the region—though those who know him wouldn’t be surprised if he jumped out of a plane to get a photo. His images recorded the best and the very worst of Miami, Latin America, and the Caribbean.

Now retired, Chapman has donated more than 750,000 photos and negatives—his entire archive—to the HistoryMiami museum, which has launched an exhibit, “Newsman: The photojournalism of Tim Chapman.” More than 300 people attended the sold-out opening on April 15.

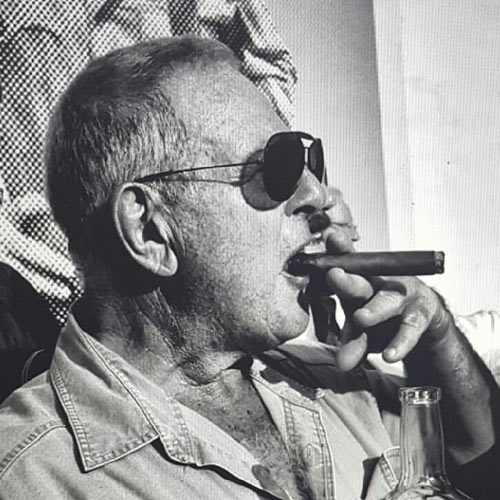

After attending the show myself, I spoke with Chapman, an old friend and former colleague, about the tales behind the pictures. He may be retired, but he hasn’t mellowed—he’s still cantankerous, and he still loves a good story.

Below is an edited excerpt of our conversation, which was less an interview and more just Chapman telling stories. Note: the post contains graphic images and some salty language.

*****

Chapman: I always felt it was historically important to save every image because it represented everything—the history of myself, the history of our town, the history of photography in that period of time, and the region. It’s all I’ve ever done.

I’m gonna light a cigar here.

CJR: Ok. Go ahead.

[After a brief pause.] The whole point of the exhibit was recording the history of everything I covered. Nicaragua for 11 years, Salvador for 10, Colombia. Miami street violence. Miami is the best news town, no doubt.

I was the Everglades guy and the news guy. One section of the exhibit is Everglades. That’s something I did my whole life, trying to show people why they should save it.

The maze of Shark River winds through the largest mangrove forest in the northern hemisphere in Everglades National Park. Photo by Tim Chapman

It was amazing to see all of the stories you’ve covered. The mass suicide images from Jonestown, Guyana, were horrible. Tell me a little bit about going down there.

I was always ready to go. I always kept a couple thousand dollars and visa photos in my locker. That day, I came in around four o’clock in the morning to work on some prints or something. I walked out into the newsroom and they had this wire machine kicking out stuff and all of the sudden it said “reports of shootings” and “possibly several hundred people dead and maybe a congressman.” I said, “Jesus what’s going on there?” It kept going.

I got my money and a couple editors came in and I said look, I’m going. What was fantastic is there were decision-makers at that time. They said, get there any way you can.

The Guyanese military was there and they had some Huey’s, American choppers. I talked my way on. When we landed, the military wouldn’t even walk in. There were hundreds and hundreds of bodies. You could smell it from the helicopter a few hundred feet up. In 80, 90 degree heat, they started decomposing rapidly. You’ve smelled bodies. There’s nothing like it.

I just kept shooting. I realized I had to shoot as much of it as I could. We only had an hour and a half because we had to get back before dark. I knew I had to record it because nobody would believe it. If you didn’t photograph that, who would believe it?

A photographer records victims of the Jonestown Massacre in the jungles of Guyana, November

1978. Photo by Tim Chapman

After covering that, hell it was easy. Nothing ever shocked me ever again.

The Herald was bold enough to run it. I wanted people to get up in the morning and look at the front page of the Herald and see what they needed to see. Not what they wanted to see. I fought that battle a lot.

At the exhibit, I read that at some point you decided to stop going to Haiti. What happened?

I first went to Haiti in ’79. I saw quite a bit, the despair, the basic rape of the island. I went back many times. I covered coups, counter-coups. I really always loved Haitians and Haiti. I always felt a real bond with them. They had been under the thumb of Duvalier and the tyranny of that. Then they had hope. I went down there during the [1994 U.S.] invasion and there was all this hope again. Aristide was put back in power, taking out the military regime. And yet again, I had hope, just like the Haitians did. Immediately after, there was so much corruption. One of the aid busses that the doctors had raised money for, they got strong-armed for bribe money to bring it into the country.

Haitians celebrate following a U.S.-led invasion in 1994 to reinstate President Jean-Bertrand Aristide. Photo by Tim Chapman

I always had a mission. My mission was not for adventure. My mission was to help change the world. But all the photos I took [in Haiti] started to repeat themselves. Those photos you see, I could have shot them in ’79, or ‘80, or ’82 or ’83, ’90, ’94. And they didn’t make a difference. I had to make a decision—I’m not going back to Haiti ever again unless it’s to rescue somebody who’s kidnapped, you know a friend of mine. I felt that way after a while in some parts of the Middle East because of the religious zealots. I was enchanted with the Middle East. I made the decision to cover things I felt I had a slim chance of helping change. There are many things where I don’t know if photography makes a difference.

You covered a lot of crime in Miami, a lot of crime scenes, a lot of kids killed. Did you ever feel like anything changed or got better?

I actually think we made a difference in the Cocaine Cowboy years. I photographed, I think, like 300 bodies one of those years. I actually do believe that us showing this incredible violence that had come to us because people like to snort lines of coke—we showed society, hey, there’s a cost. I do believe that our coverage, people finally said, you know this is crazy. I do believe that Miami over a period of time changed that. I do believe we made a difference.

A man was shot and killed and stuffed in the trunk of a car that was left in an apartment building parking lot, one of the many victims of violence during Miami’s “cocaine cowboys” era. Photo by Tim Chapman

The scanner is the heart of the city. The best way to get out of a shitty assignment was to say “Hey, you want me to go get that mug shot, or do you want me to shoot this quadruple murder in Medley?” I got out of half the shitty assignments because I found better news.

Tell me about the iguanas falling out of the trees when it got cold.

I dictated a story to Casey Frank, a great editor at the Herald. In that one I got a quote from a ranger who said, ‘Iguanas are falling from the sky like rain.’ And Casey said “what?” I handed him the phone and said, ‘tell him what you just told me.’ Casey made sure. It was just too perfect, the quote.

Because he doubted me, I took one of the comatose iguanas and put him in my camera bag and I took him in and put it on his desk. It was barely blinking its eye. And I said, “don’t ever doubt me again.” It got near the computer and started warming up.

You always had a thing for reptiles.

I used to supplement my income by catching rattlesnakes and selling them to a scientist for $3 a foot. One day, I was running late to work. I had a duffel bag with three of them in it. After work, I got down to my jeep and somebody had taken a box of bolts out of my jeep. They were scattered around.

Then I found the duffel bag. They had dropped it after checking out what was inside. They were only pygmy rattlers. They’ll bite you, but your hand will just swell up—it hurts, but they won’t kill you. Luckily, when they dropped the duffel, the flap fell back over it. The snakes were comfortable enough. I counted. All three were still in there.

Nobody ever broke into my fucking jeep again. Better than a goddamn alarm. But I almost released rattlesnakes in front of the Herald building. I didn’t tell anybody about that for years.

Tim Chapman in his M-38 Willys 1951 Military Jeep in the Everglades, photographed in 1972 catching live rattlesnakes to earn extra money while he worked part-time in the Herald photo lab. Chapman’s first photo in the Herald was of an Everglades fire he shot on one of his snake hunts.

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.