Sign up for The Media Today, CJR’s daily newsletter.

Black Lives Matter may be the largest movement in US history, yet as the Justice for George Floyd protests enter their third month, there is a sense that the national news cycle, outside unprecedented events like the federal occupation of downtown Portland, has largely moved on. Likewise, many protesters have also moved on—to social media, where they can stream videos of police brutality on Instagram and TikTok, form neighborhood watches on Facebook, and exchange encrypted information over Signal. I asked protesters, organizers, and citizen-journalists how they’ve been staying informed and informing others, and whether this moment has changed their views on traditional media.

To be honest with you, I’m not even watching the news. They’re going to give you their story. I’m out here—I am the news for our people.

Photo credit: Misha Cohen

Joseph Blake, forty-eight, club promoter and barber. A Portland native, Blake has livestreamed the city’s protests on Facebook for fifty-six nights in a row, since June 1. His videos are viewed by thousands.

When the protests first started, you would hear about them just on social media. They call Portland a city, but I call Portland a big town. Word gets out super fast. Right now, it’s Facebook. People are going live. Twitter, you can put a video on and talk about it. Twitter is popular with celebrities and bigwigs that have the blue check. Regular people like us, we don’t usually get too many Twitter followers. I would say Instagram a little bit, but it’s mostly Facebook, because you can add groups. Just like with the Wall of Moms—they started a Facebook group that I’m a part of. I started a Facebook group called We Gone Be Alright.

My kids are into that TikTok stuff—I can’t get into it. But that’s what got me started in this. I used to be the type who sat on the couch and watch TV and be like, “Them fools is crazy, I ain’t going out there with them crazy-ass fools.” Until I saw my son and daughter’s pages. My son, twenty-three, is a professional photographer. He’s capturing so much stuff, it’s crazy and amazing. And my daughter, twenty-six, is out there protesting, too. So I was like, “Well, let me see what’s going on.” I went and I got the bug, and I’ve been out there every night since then.

To be honest with you, I’m not even watching the news. They’re going to give you their story. I’m out here—I am the news for our people. I’m doing a lot of livestreaming for people who can’t get down there to see. I give it to ’em rough and raw. I’m right in the thick of things. I’m getting shot. I’ve been shot four times by rubber bullets just this week. I come home and I have to take my clothes off outside because there’s pepper-spray dust.

Anything you’ve seen on the national news coverage, man, I’ve seen it with my own eyes.

I never thought in my wildest thoughts I would be down there doing nothing like this. I didn’t know nothing about protesting, only what I seen on TV. But now it’s like I’m an expert.

Photo credit: Ilaria D’Alessandro

Jah’I Bazin, seventeen, rising freshman at Seton Hall and a volunteer with Street Riders NYC, which leads thousands of bike protesters on weekly “justice rides.” Since the killing of George Floyd, Bazin estimates, he’s been to sixteen protests, where, among other things, he has been struck by a van and called a racial slur.

I went to the Million Man March with my dad in DC in 2015. As a twelve-year-old boy, I didn’t see the importance of it until this summer, when I started protesting on my own. When you see that it’s not just people that look exactly just like you, you get a sense of hope because your people aren’t the only ones that hear the struggle or see the struggle. They might not feel the struggle, but at least we have other people trying to help us out in our time of need.

I stay informed—obviously you have the internet, you have Instagram, Twitter. Most of the protests I’ve partaken in have been through Street Riders, through their Instagram. Or else it will be a friend texting me, or their Instagram account. It’s pretty simple. I’ve seen people say, “Oh, I don’t know where to go. I don’t know when things start. I don’t know who to talk to.” When, really, it’s not like the protest organizers are celebrities or gods—they’re regular people just like you. You can talk to them and ask.

Photo courtesy Isabella Moles

Isabella Moles, twenty-one, a founder of Central Pennsylvania Advocates for Justice. I met Moles at a Pride event in Mifflinburg, Pennsylvania, population 3,540. She was wearing several rainbow pins and a yellow shirt that read sounds gay i’m in.

It’s young folks who are coming together. I think we have the gift of technology and social media, even when we are apart, to unify and make sure that we get progress. We see that with TikTok too. I find most of my shit from TikTok, even videos of police brutality. When I talk to my ninety-two-year-old grandpa, whose father was a member of the KKK, when I’m having conversations with him, I use TikTok. These are actual things that my generation was able to record and document as proof of violence and police brutality. And when I show him that, the evidence is right there and he can’t dispute what he’s seen with his own eyes.

One of my main sources has been through grassroots journalism like Unicorn Riot. I know for a fact that they are reporting the closest thing to the truth.

Photo courtesy Ma’iingan Sherritt-Stone

Ma’iingan Sherritt-Stone, twenty-one. During the curfew, Sherritt-Stone volunteered with a Minneapolis-area nonprofit working to provide protesters with assistance and information in real time. Working sixteen- to eighteen-hour days, he followed police scanners, helped to encrypt organizers’ information, and created Facebook groups that became neighborhood watch groups. He also assembled a lengthy, encrypted Google document on known white supremacist activity in the area. The list included known plate numbers, people, and how to recognize when there might be an imminent attack. He described “a bunch” of school alarms and domestic violence calls before “things really hit the fan.”

One of my main sources has been through grassroots journalism like Unicorn Riot, which has done a really good job reporting things from not only Minneapolis, but across the US. I know for a fact that they are reporting the closest thing to the truth.

ICYMI: How Unicorn Riot covers the alt-right without giving them a platform

A big problem that I had, especially with my own family members—I have some relatives in Florida—was with people believing that we were destroying our own businesses. When I was covering police scanners, I was reporting on white supremacist activity and the tactics they used. It was very clear, hearing on police scanners, who was doing the damage. There was a lot of bait-and-switch. Somebody would set the alarm off at a school. And because it’s a school, the police have to respond to that, and then there’d be nobody there. And then while they were doing that, other buildings that were known Black- and Brown-owned businesses were being targeted. Things like that weren’t being reported on whatsoever. So it was almost a battle having to explain what was happening to people outside of Minneapolis. A big part of that was the lack of media coverage and what the media painted from just hearing reports and then spinning their own stories.

So I have a lot of mistrust with media. I don’t follow many bigger outlets because I and other nonprofits reported to some journalists at the New York Times and I don’t think they really did anything with that information.

I definitely sit down and watch some Fox. I like to see how the same story is played out in very different ways.

Photo courtesy Khadija Ahmed

Khadija Ahmed, thirty-two, restaurant manager. Two days after George Floyd’s killing, Ahmed pivoted from batching cocktails to providing food, water, and supplies to protesters through Inbound NYC, a mutual aid group she cofounded.

There’s three forums that you go through. One is the people you’re messaging, that you already have the numbers of, that you’re close to. Then there’s Signal chat, the different groups that are talking together. And there’s Instagram, the groups that post schedules for protests every day. Protect Protesters and Justice for George NYC are the main ones that I’ve seen. Everything is Instagram. Instagram is the one where you can catch the most age range, from eighteen to sixty.

I grew up in DC. I had a political job, and I left because I hated it. I need all sources of news. I watch CNN and MSNBC, but I definitely sit down and watch some Fox. I like to see how the same story is played out in very different ways. I still read articles. I read the Washington Post and the New York Times. I read The Guardian and The Independent. I’m definitely a three-sources girl. Watching non-American news is really interesting lately. When you’re watching Al Jazeera or the BBC, it literally looks like America is a war zone. The way we used to judge all these other countries, we’re being judged in that way now‚ with video footage.

Photo credit: Brian Davidson

Christine Rossi, twenty-nine, server and volunteer with Street Riders NYC.

When my roommate and I came home every night from the protests, we would watch Fox News and CNN. Not because we believed their narrative, but because we needed to see what it would become. We know we’re in our own bubble, and we just needed to see what the other bubbles are like out there. They’re not covering protests. The people in our inner circles are out there, taking photos, taking videos, and I’m seeing all of that raw shit on Instagram. But it’s nowhere on the news. So Ronald Weaver II, Mel D. Cole, Nate Brown, Budi—that’s who we’re getting the news from now. They’re not news anchors, they’re photographers, videographers.

It’s almost like going home and watching a fantastical movie that’s been falsely made about everything that’s going on. It feels like another world. I’ve felt like this for probably the past decade, but right now it’s being exposed to its fullest, seeing what a sham the media has become, along with everything else: the cops, the media, our government.

We will still watch Democracy Now! I do think it’s a good general way of getting news. But I think whatever news you watch, you should be in contact with all different kinds of people.

Jack Duren, left, and James Carthel. Photo credit: Rick Simpson

Jack Duren, eighty, a retired art teacher, makes signs for weekly protests at Rose Villa, a retirement community just outside of Portland.

There are two retirement communities side by side here. We’re putting maybe a hundred people out on the street in front of both. We only do it for about an hour, because we’re old farts. But these are very active retirement communities. People are not sitting on their porches in rocking chairs waiting to die.

I have three primary news sources: one is The Oregonian. There’s also Willamette Week, which is much more independent and subscriber-supported, and a third one called Bridgeliner. We watch the local news as well as PBS NewsHour. I’m skeptical of a lot of stuff online. I had to bail out of Facebook because it got too awful. I don’t like going to bed mad at this age.

A lot of people here use NextDoor. A couple posts on there were like, “Doggone it, can’t they move their protests down the street, so I don’t have to listen to cars honk?” The thing is, it’s one hour a week. Gimme a break. The person said, “Why do they have to encourage the car-honking?” Then there was one employee of Rose Villa that posted, “We think they should be honking more.” I liked that one.

There’s a sense of narrative structure and narrative construction that doesn’t seem to reflect what you are watching happening in real time, where there isn’t one narrative.

C.J. Holmes, thirty-three, a sales director who was laid off at the beginning of April. When he got in touch, Holmes described himself as a “medium” protester, attending about a dozen actions in Chicago.

When I read mainstream coverage, it feels very delayed. I have a friend from college who lives in Portland, and she was posting and reporting about it, being a citizen, about a week before it broke more broadly. Sometimes I’ll read to get that official view, that language, to see how it was articulated, but it’ll be more about fact-checking and understanding what people who are not in my headspace are saying. I’ll occasionally learn a nugget, but it’s deeply unsatisfying. It’s not a place I go to feel informed, because it’s so slow. Also there’s a sense of narrative structure and narrative construction that doesn’t seem to reflect what you are watching happening in real time, where there isn’t one narrative. As we know, there’s never one narrative—it’s intersectional, it’s constantly changing.

I check every box of privilege. Every single one. I’ve been recognized as a leader probably since I was ten. So entering these spaces and trying to do the quote-unquote right thing, it’s very difficult until you decenter yourself. Because when you are centered, you can’t listen or learn. Even if you’re allowed in the room, the way that you experience that room is going to be untrue, or filtered, or affected, or prevented.

Photo credit: Nicholas Page

Mahadi Lawal, twenty-six, graphic designer, event planner, and an organizer of Occupy DC, which has occupied Black Lives Matter Plaza and is currently hosting yoga sessions in the space.

May 29 was the first day that the protests got violent—tear gas and everything in front of the White House. I went home after that day realizing how serious things were, and I formed a Signal group chat with friends and acquaintances that I knew were interested. For the next few weeks we used that chat; I called it “America.”

Instagram has been the key tool. When I got arrested on the morning of June 24, there was a huge campaign all over Instagram and Twitter. There were videos of my arrest, and all my friends were like, “Free him.” So I gained a lot of followers like that. I started to use my account more to be informative. After the sit-in, we made the Occupy DC Instagram. We gained one thousand followers in a week. That’s been our main way of getting the information out, that and Signal.

I probably spend 80 percent of my time scrolling through Twitter. I get most of my news through Twitter, just because of how fast it is. When I need information on protests, I’ll go on the Instagram pages of accounts like DC Teens Action.

I feel like the city leadership has come to a consensus that they’re just not going to respond or acknowledge the protests and the violence committed by the police, that it’s just going to go away. The only DC media that’s been consistently covering these things has been the Washington Post.

I went from throwing parties to now having protests. This is way more fulfilling.

Photo credit: Kavi Peshawaria

Etienne Maurice, twenty-eight, actor, filmmaker, activist, and organizer of Walk Good LA. Each week the group hosts a 5k run for justice and yoga for restorative justice.

I started out by making my own flyer on Adobe Spark. I made the flyer, I posted it on social media, and I also texted a lot of friends that live in my neighborhood. I made it grassroots. Then I started finding out about other Instagram profiles that had a huge following that became an online bulletin for protests in the neighborhood. One Instagram called In This Together LA have been a major help—they have over 100K followers—and they have short blurbs about what each protest is focused on. I can’t tell you how many new people have come to my protests because I submit to that account. Also, a big help is to continue to post the photos and video recaps of what took place that day. That next day I hit the ground running, I get on my computer making those one-minute recaps of what took place that day, so that people stay engaged, they see it happened and will continue to happen.

It’s important to be of service in our fight for justice. That’s been the biggest lesson for me. I went from throwing parties to now having protests. This is way more fulfilling. I’m using the same organizational skills getting people together in one place that believe they’re going to have a transformative experience.

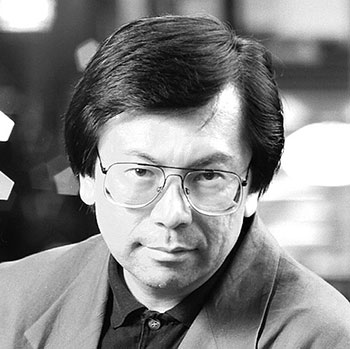

Photo courtesy Corky Lee

Corky Lee, seventy-two, activist and photo documentarian. Lee, a Queens native whose business card describes him as the “undisputed, unofficial Asian American photographer laureate,” told me he’s gone to more than a thousand protests over forty-nine years.

Before they had the internet, there was something called a phone tree—you ever hear that term? This was the sixties. If you wanted to organize a protest, at the end of a public meeting, or teach-in, everyone would get a list of phone numbers, and you would call, let’s say, twenty people, and hopefully each person would call twenty people. This to find out what’s going on and where it’s going to happen.

With Occupy Wall Street, in 2011, it all happened in one location. That was great for the NYPD—they knew if anything was going to happen, it would be in Zuccotti Park. Now the NYPD has to monitor social media more than ever before. It’s not going to be in mainstream news or people putting up flyers. A lot of stuff will happen spontaneously.

Another thing about Occupy Wall Street, there weren’t many leaders, so the news media couldn’t figure out who was representing the people. Pretty much the same thing is happening here. Mainstream media doesn’t know who to go to speak to, so they’re grabbing anyone who’s willing to speak to them. But those people may not necessarily be the organizers or the leaders. This was something that wasn’t learned from the civil rights movement of Martin Luther King, Malcolm X, and so forth—those guys were well organized. Without some identifiable leaders in the current George Floyd situation, I think that the general public is in a bit of a quandary and they don’t know what’s happening.

Hammad Ahmad, twenty-five, business analyst, Atlanta. In early June, Ahmad and his sisters raised over $2,400 for local bail bonds and to deliver a van full of water and snacks to protesters.

I’m not on Twitter. Just seeing the things people tweet makes me angry. But if you were to talk to any other person who would be going to these, I think they would say that Twitter is what they would rely on. There was one Twitter account called Where Is the Protest in Atlanta? Literally every day they would post and then pin where they would have protests in the metro Atlanta area, even in the suburbs. There were a few Instagram accounts that I followed that posted regular updates. In terms of finding out where we could drop things off, whenever we would find out about a protest over the weekend—it was kind of hard to go during the weekdays, just because of work—we would reach out to the organizers and go from there.

Honestly, I don’t really look at the news, because it just angers me. It doesn’t really make sense to me to go somewhere that isn’t covering it well enough. I don’t share these types of news sources. I don’t share CNN.

Photo courtesy Tiana Rawls-White

Tiana Rawls-White, twenty-three, hospitality industry. Rawls-White went to her first protest on June 28 and spoke at the recent Rally for Justice, organized by the group If Not Us, Then Who?, in Williamsport, Pennsylvania.

On Facebook, you have the opportunity to see what other people are saying and how they’re reacting to these things, and it really shows people’s true colors. It also gives you the opportunity to have conversations.

I try my best to watch Fox, even if it’s something I won’t agree with. It’s like going to war with somebody and wanting to know what the other side is thinking. The best way to do that is to listen to what they’re saying. Because you’re not going to be able to inspire people to do better and to change if you don’t know where their head is at to begin with.

There was a woman that I had reached out to. She had said, “If you support BLM, then you’re a racist,” or something like that. And I was like, “Hey, do you think I’m a racist? I don’t think you’re a racist—you’re one of the nicest people I know. But sometimes the things that you post really upset me and it scares me to think that you would think this way. And I get very disappointed in you, and honestly if you were anyone else I probably would have unfriended you by now. Why don’t we talk, let’s get lunch, you hear me, I hear you, and let’s go from there.” Because nothing’s going to get resolved if people don’t talk.

She’s my ex’s stepmother. After he and I separated, she and I kept in contact. She never responded about getting lunch—she saw it, but she didn’t say anything. I’m like, “Okay, I’ll just let it go. If she wants to talk, she wants to talk.” But I at least put it out there that I’m willing to hear her out.

THE MEDIA TODAY: A mammoth explosion, tears, and resilient journalism in Beirut

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.