Sign up for The Media Today, CJR’s daily newsletter.

From her office overlooking Frenchmen, New Orleans’s most musical street, Jan Ramsey commands OffBeat magazine, which has reported on the city’s music scene in painstaking detail for three decades, promoting musicians who might otherwise never receive a lick of press. Ramsey, who is 68, has recently let her trademark fire-orange hair go grey, but nonetheless radiates color in her quiet, messy office. Her handicap keeps her immobile; she doesn’t go out to the nightclubs much anymore, and only her three young employees and her husband and publishing partner, Joseph Irrera, see the amazing outfits and accessories she wears to the office. On the day I visit her, musical-note earrings dangle from her lobes, a green scarab ring nearly eclipses her left hand, and a huge ceramic macaw hangs around her neck.

Ramsey gestures out the big windows onto Frenchmen’s typical late-afternoon crowd of tourists.

“I can’t stand the cover bands that play at this restaurant down here,” Ramsey says. When I suggest that OffBeat may be partly to blame for Frenchmen turning into the new Bourbon Street by advertising it as a musical mecca, she surprises me by shrugging the comment off.

“Pretty much everybody in the music business in New Orleans loves Jan,” says Scott Aiges, who later became the Times-Picayune’s first official local Jazz and Pop writer, and today works for the New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Foundation. “But it’s also fair to say that you aren’t really in the music business in New Orleans unless you’ve had a fight with Jan at some point.” It also seems fair to say that, if Ramsey weren’t a fighter, the world wouldn’t still have OffBeat.

Ramsey, right, with husband and OffBeat editor Joseph Irrera. Courtesy of Jan Ramsey/OffBeat

Ramsey studied business at the University of New Orleans, and famously finished her bachelor’s degree from a hospital bed after being hit head-on by a drunk driver—which is why she now depends upon a mobility scooter. In the mid-’80s, Ramsey, a New Orleans music addict since her girlhood, made it her mission to educate everyone she could about the business of music, and how much New Orleans music helped everyone’s financial bottom line. She joined music-advocacy nonprofits, and started a couple others.

“I think I pissed a lot of people in the music community off,” she says. “I was like this outsider coming in, even though I was born here. I was perceived as a dilettante.” Ramsey also felt people minimized her because of her gender. When she met Cosimo Matassa, the producer whose recording studio birthed Little Richard’s “Tutti Frutti,” he regarded her with skepticism, according to Ramsey. “I was wearing a suit and pantyhose and telling people what to do, and people didn’t like that,” she says. Ramsey’s traditional response to sexism in the music and media world? “Just watch me, motherfucker.”

Related: No Depression survives as an ad-free quarterly—nearly a decade after it stopped printing

Ramsey came on the scene after the death of New Orleans’s popular culture magazine Figaro, and just before publisher Connie Atkinson ended her decade helming local music publication Wavelength. Both publications inspired Ramsey’s first edition of OffBeat, through which she hoped to cover music from a business perspective as well as a cultural one. Initially published as a one-off for tourists, OffBeat’s first issue targeted 15,000 conservatives visiting New Orleans for 1988’s Republican National Convention. Ramsey, a staunch liberal, personally distributed OffBeat at the convention and left copies of that inaugural issue—small, black and white on the inside, with a color silhouette of a saxophone player on the cover—in the lobby of every hotel that would allow.

Jan Ramsey with New Orleans musician Davell Crawford at JazzFest in 2012. Courtesy of Jan Ramsey/OffBeat

Deeming OffBeat No. 1 a success, Ramsey ground her heels down, stomping around town selling ads in order to drop a new issue every three months for that first year. In 1989, OffBeat went monthly. “I had no investors, and funded it with my credit cards,” says Ramsey. “I went through several years of real, dire poverty. I lost my car, and my house.”

Two years and a couple dozen issues of OffBeat later, the New Orleans Times-Picayune hired Aiges, whose concerns for music as a business made him something of a competitor for Ramsey. “Until then, music was only covered as a cultural institution that needed to be held up and revered,” says Aiges, who also aimed to cover the business of music, and its financial position in the city.

Shortly after, Ramsey hired her first full-time editor, Keith Spera, who’d returned home to New Orleans from college in Texas. “I was young and willing to work hard for not a lot of money,” says Spera, who later served 19 years as the Times-Picayune’s music editor. “And I saw it as an opportunity to shape this publication about New Orleans’s music world.” OffBeat was produced, at the time, in Ramsey’s living room, with the help of a small computer with a six-inch screen. Spera often fell asleep on Ramsey’s couch while working to meet deadlines.

If New Orleans is still the music capital of the world, you wouldn’t know it from reading most local publications—unless, of course, you read OffBeat.

OffBeat has since published work by almost every New Orleans music writer and editor of note—’60s protest-poet icon John Sinclair, nutty historian Ned Sublette, renowned authors Tom Piazza and Michael Tisserand. The OffBeat morgue contains the world’s most thorough and detailed documentation of New Orleans’s music over the past three decades, starting with Sinclair’s 1988 feature on underground Mardi Gras Indian culture, and stretching through modern day cover stories on local breakout acts like Tank and the Bangas and The Revivalists.

“We put rapper Mystikal on the cover when he was still doing indie stuff,” says Spera. “They let me do a 6,000-word Q&A with Snooks Eaglin. I interviewed Alex Chilton a bunch. OffBeat still reviews every single record that comes out in New Orleans. And now, all that is part of the historical record.”

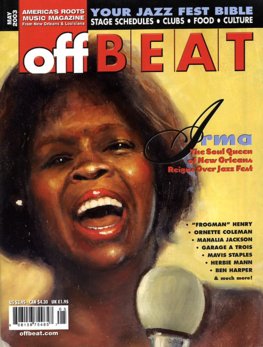

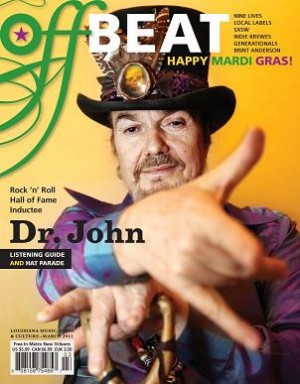

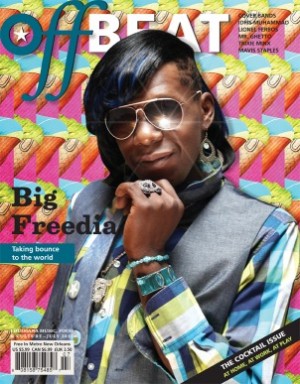

OffBeat covers featuring, clockwise from the top left: Irma Thomas, Dr. John, Jan Ramsey on OffBeat’s 25th anniversary issue, and Big Freedia. Images courtesy of OffBeat.

Joseph Irrera, now Ramsey’s life partner and OffBeat’s editor in chief, first came into the office in 1995 to buy ads to promote the bands he managed. He says he’s brought stability to the magazine. “I am better at the business end,” says Irrera. “Jan keeps the magazine alive, but I am the one who keeps it running.” Ramsey, in turns, says Irrera is “the person I yell at most.”

Irrera has had to make many hard decisions in order to keep OffBeat running. “Music clubs mostly advertise via social media now,” grouses Irrera, who emphasizes the stress of sustaining a magazine on life support. “Let’s just say it’s good that both she and I are on social security now, so we don’t need our salaries,” he says.

Ramsey and Irrera have also kept OffBeat afloat by publishing extras like the yearly Jazz Fest Bible and the thick Louisiana Music Business Guide, which for 16 years listed the name, phone number and address of almost every musician and music-related business in New Orleans—an effort that ended with Hurricane Katrina. Ramsey still coordinates an annual Best of the Beat Music Awards and hosts a yearly Music Business Awards. “She’s the only one who does that…recognizing the bookers and promoters as well as the artists,” says Scott Aiges. “She goes above and beyond to make sure everyone gets recognized.”

When digital doom first came knocking for print publications, Ramsey proved quick on her feet, commissioning one of the first websites of any Louisiana media entity. OffBeat’s digital newsletter launched 12 years ago, a move that put it ahead of many peer publications. “Though I’ve had to stomp my feet and throw tantrums to get the staff and Joseph to commit,” says Ramsey.

Post-Katrina, New Orleans’s Gambit Weekly scaled back its regular music section in favor of intermittent coverage. Not long after, the city’s paper of record, The Times-Picayune, liquidated its music writing position, and handed over all cultural coverage to one overwhelmed art critic, former OffBeat scribe Doug MacCash. (Spera says the paper told him his beat would change, to include topics such as education and healthcare. “And I was like, ‘What? Why would I want to do that?’”) The New Orleans Advocate scooped up several orphaned Picayune music writers, but underuses them. If New Orleans is still the music capital of the world, you wouldn’t know it from reading most local publications—unless, of course, you read OffBeat, which today offers around 70 glossy, full-color pages for free each month at around 600 New Orleans hotels, restaurants and other businesses. OffBeat is also mailed to another 4,000 out-of town subscribers.

Ramsey admits she has ruffled many feathers over the course of 30 years, and says her impatience has “probably worked against the magazine and the revenue that we could generate.”

Current and former colleagues, though, are quick to defend her. “It’s a tough business, and she has to be tough to keep it going,” Spera says. “Fact is, she has kept an independent music magazine alive for 30 years. And that is just miraculous.”

ICYMI: Detroit’s game-changing sportswriter on a half-century of work

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.