Sign up for The Media Today, CJR’s daily newsletter.

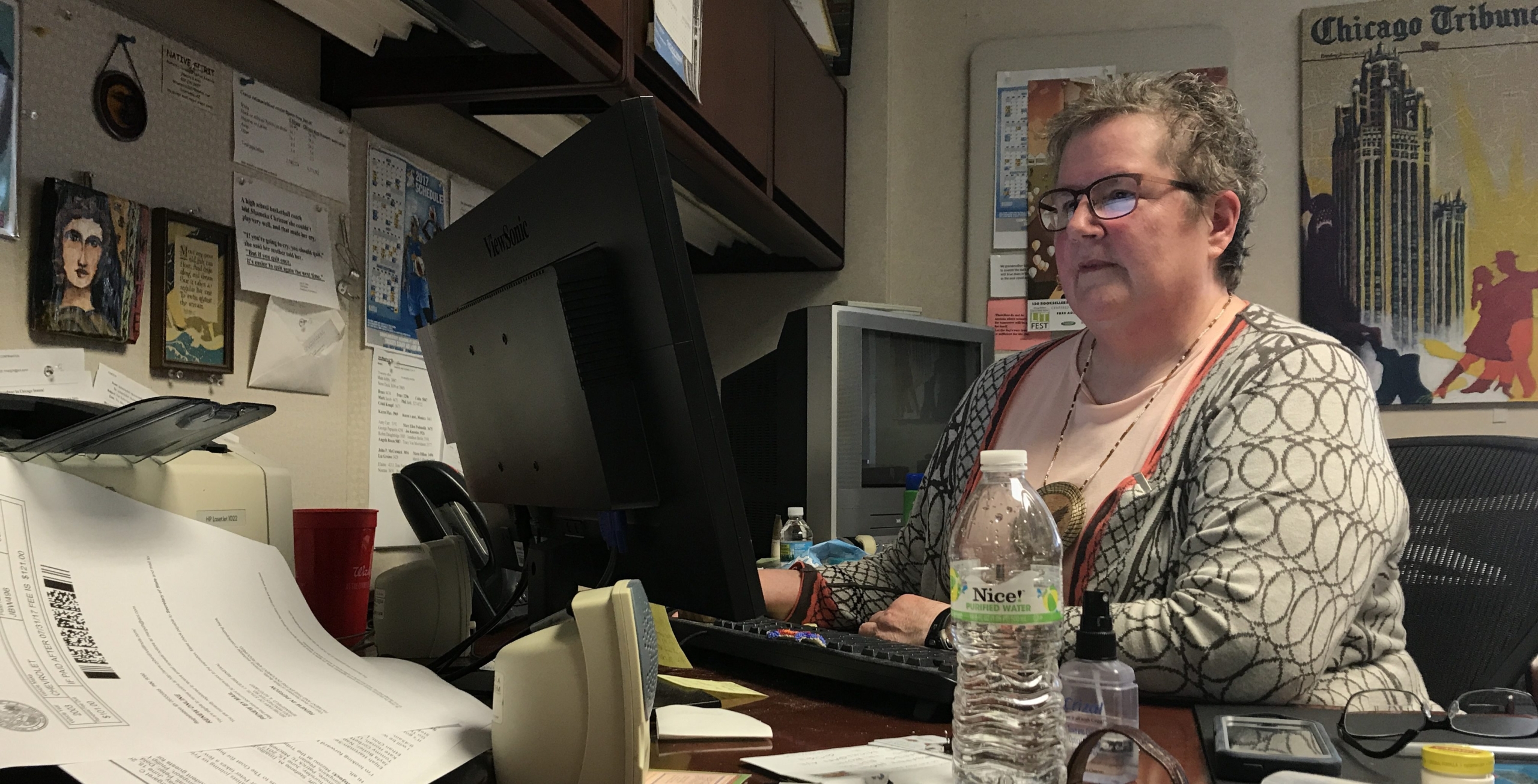

MARGARET C. HOLT JUMPS UP from her chair in her sunny office at the Tribune Tower, a building the Chicago Architecture Foundation calls a “cathedral for journalism.” If the building is a sacred space, then Holt, as standards editor, is its bishop, enforcing the Chicago Tribune’s ethics policy and making certain that mistakes get corrected.

At the moment, Holt is looking for a book. She uses her finger to scan the shelves until she finds it. “Have you read this?” she asks, holding up a copy of Jack Fuller’s News Values: Ideas for an Information Age, a 1996 book about the ethical issues confronting newsrooms. Fuller, a Pulitzer Prize-winning Tribune journalist and former publisher and chief executive who died last year, helped bring Holt to Chicago from the South Florida Sun-Sentinel in 1993, setting her on the path to become one of the most influential women at the paper and a powerful voice across the industry for tracking errors. In 2015, Holt, a Native American from Missouri, was added to the Tribune’s masthead—a recognition of her and the importance the paper places on her job.

ICYMI: ‘Thank God the brain cancer waited for the Pulitzer’

Holt is not an ombudsman or reader representative. She does not write public columns. The Tribune folded its public editor position into the standards editor job in 2008, in a move reminiscent of many made in newsrooms around the country. “I am just the standard bearer,” she says.

At a time when the president of the United States wages war against the news media and social media has amplified the haters, Margaret Holt’s dogged belief in standards and doing right by the community it serves is a lesson that others should heed. A 2017 survey by Cision, a media analysis company, polled more than 1,500 journalism professionals and found that 91 percent believe “that the media is somewhat or much less trusted than they were three years ago.” Even if you roll your eyes (or take a drink) every time someone uses the term “fake news media” to describe the press, mistakes—even ones that were not made intentionally—chip away at the news media’s credibility.

At the Tribune, Holt safeguards that credibility.

“I know more about errors,” she says, “than anyone in Western civilization.”

AS STANDARDS EDITOR at the Tribune, Holt created and oversees a system for tracking editorial mistakes. The errors are entered into a database, with information about how they occurred. Holt tracks them to find patterns and offer solutions to prevent them from happening again

Perhaps more impressive, Holt encourages an environment of self-reporting in which staff members essentially tell on themselves when an error occurs, even in the absence of a complaint from a source or reader. Her job isn’t to shame people for making a mistake, Holt says. “We own our mistakes, we correct them and we move on,” she says. “People want to do good work.”

That self-reporting culture defines Holt’s legacy as a leading advocate for accuracy in media, says Carol Nunnelley, an Alabama journalist and editor who developed the National Credibility Roundtables Project and the Associated Press Media Editors’ NewsTrain program. But the same culture is not necessarily ubiquitous among news organizations. If you work at one, you probably know that.

TRENDING: Why an NBC reporter left his job to become a Lyft driver

“I think that hardly anybody else has bought the concept of having accuracy as a set-aside program and process that is used by itself, and has, as a main component, recruiting your staff to like this program and feel proud of it as a special way of behaving with your audience,” says Nunnelley, co-founder of the Birmingham Watch investigative news initiative, where she currently works as an editor. “That’s very distinct” at the Tribune.

Our main product is our credibility. It’s our main asset. It’s not something to be frittered. It’s the most important thing we have to offer.

Inside the Chicago Tribune newsroom, Holt is known as a brilliant, quirky editor. Her pertinacity has, at times, irritated some colleagues: She is willing to confront managing editors, and got rid of the TV sets in the sports department when she first arrived. (They were not returned while Holt was sports editor.) But it also has made allies of others who share her belief that news organizations should promptly admit when they are wrong.

“Inside the newsroom, there are differing opinions about her likability and about her accomplishments,” says James Janega, former Trib Nation manager who considers Holt a mentor. “But I think there’s general agreement on her effectiveness and what she adds to the newsroom.”

Janega, a former war correspondent who left the paper in 2015 and is now a management consultant in Chicago, quotes Holt like she quotes Winston Churchill. He’s visited her hometown in Missouri and remarks on her humble upbringing.

“What motivates her is truth and community and that is a force in a lot of her career,” he says. “I think this is a particularly timely inflection point in American journalism, which is coming to grips with trust and at a base level reducing errors, increasing accuracy, increasing relevancy. You concentrate on engagement in a community to create that relevance through that broader truth, through more connections. It’s done with influence and not authority.”

Mark Jacob, the Tribune’s associate managing editor for Metro, says he and Holt are “philosophical allies” in their efforts to identify, analyze and avoid mistakes.

“Fairness and accuracy go hand in hand,” says Jacob. “We are in a really weird period in journalism. We have multiple platforms. We’re doing video. We’re doing online stories. We’re doing all kinds of things. When I’m talking to reporters, I always say our main product is our credibility. It’s our main asset. It’s not something to be frittered. It’s the most important thing we have to offer. You can’t waste it with sloppiness.”

You have fact checkers catching politicians in lies. That creates these high standards. We have to live up to our own standards.

News organizations will make mistakes, he notes. The way to maintain credibility, according to Jacob, is to own up to it, explain what’s right and “just make it right as much as possible.”

He says news organizations are hypocritical when they don’t hold themselves to the same standards as others. “You have fact checkers catching politicians in lies,” he says. “That creates these high standards. We have to live up to our own standards.”

The job of enforcing those standards at the Tribune falls to Holt.

Holt and I do not talk about Donald Trump or his Twitter account. We talk about the tiniest of errors—the little things that readers notice, which are also the big things that matter.

DURING MY VISIT to the Tribune Tower this summer, Holt reads aloud from page 13 of the Fuller book. “The quality techniques used in other industries should be applied in the newsroom, beginning with the elegant idea that obsession with quality saves time and effort and that excellence comes most reliably as people first do the work, not through elaborate fail-safe mechanisms.” The section concludes: “It is as dull as making sure the doors on automobiles open and shut properly. And just as vital to the continued success of the enterprise.”

Each book on Holt’s desk is feathered with colorful sticky notes to mark the points she wants to make about accuracy during a surreal and occasionally perilous time in American politics. But this is not Washington or New York. This is Chicago. Holt and I do not talk about Donald Trump or his Twitter account or the White House press briefings. We talk about photo captions and the tiniest of errors—the little things that readers notice, which are also the big things that matter.

Holt rarely uses social media, except to post benignly about sports, the arts and Chicago life. She lives what she sells, which is old-fashioned objectivity and fairness

Bruce Dold, the publisher and editor-in-chief of the Tribune, declined to comment on Holt’s role in the newsroom and the paper’s commitment to the standards editor position. “I’m glad you connected with Margaret,” he tells me. “She’s going to speak for us on this story.”

Tim McNulty, the last public editor at the paper, says he isn’t sure that the role of public editor is as important anymore as having a standards editor. When The New York Times eliminated its public editor position a few months ago, it left its standards editor in place. Most smaller news organizations do not have a public editor or ombudsman, and many that once did have eliminated the position.

“In the last nine or 10 years, you can get feedback and you can generate lots of feedback to the newspaper through social media and other places,” says McNulty. “I don’t know if the public editor is essential anymore or important to have. But standards is important. Here is someone who can enunciate or articulate what a newspaper expects. It’s good to have someone who is keeper of standards.”

Nunnelley, who wrote a guidebook for editors called Building Trust in the News, says it’s a shame more news organizations haven’t adopted the culture that Holt and the Tribune have created.

“I do believe having a voice like Margaret’s in the newsroom is extremely important to the culture,” says Nunnelley. “That, however, is for ourselves because that’s what we want to do.” News organizations should also be modest about the responsibilities they have to their communities, says Nunnelley. “We have to have humility about how hard it is to do what we promise to do, which is to be accurate and truthful and fair.”

When I contact Holt to verify a couple of things for this story, I apologize for bothering her. “I hate errors,” I tell her. She laughs and says, “Welcome to my world.”

“Errors in and of themselves are not necessarily bad,” says Holt. “What’s bad is when we don’t learn from our mistakes and persist in making the same ones over and over and over.” She emails me Portia Nelson’s “Autobiography in Five Short Chapters,” about learning to walk around a hole instead of continuing to fall into it—an apt metaphor for just about everything right now in journalism.

ICYMI: “I don’t tweet. I don’t care.”

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.