Sign up for The Media Today, CJR’s daily newsletter.

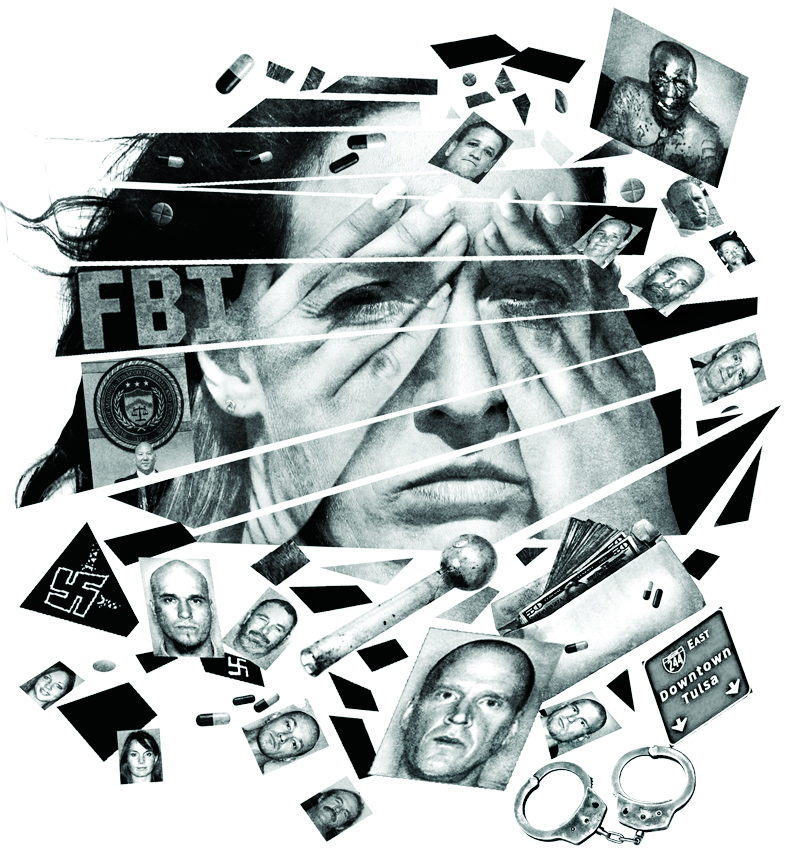

THE DALLAS MORNING NEWS LAST WEEK unveiled “My Aryan Princess,” a seven-part “seat-of-the-pants crime drama” about a troubled FBI informant who brought down a vicious gang of white supremacists while living among them. Carol Blevins helped put at least 13 members of the Aryan Brotherhood of Texas, some of whom she considered friends and even lovers, behind bars. Throughout it all, Blevins nursed a heroin addiction, wowed investigators with her memory for details and aptitude for spy work, and more than once narrowly escaped the fatal consequences of exposure as a snitch.

Morning News reporter Scott Farwell spent the better part of two years unraveling Blevins’s story, a bounty of time most reporters in metro newsrooms can only dream of. In all, over 15 staffers touched this multimedia-rich presentation, from interactive design to audio production to the hours photographer Nathan Hunsinger spent at Blevins’s apartment capturing intimate portraits of a subject who continues to wrestle with addiction and the dangers of her past life.

The mega-popularity of Serial and other multipart true-crime deep dives has spawned no end of interest in the genre, in podcast form and beyond. Last year, the Los Angeles Times published a gripping six-part account of a PTA mom framed by her neighbors. The LA Times opted to publish one chapter at a time online over the course of a week. After much internal debate and weighing of options, the Morning News team decided to drop all seven parts of “My Aryan Princess” at once, Netflix-style, and roll the story out in print in serial form, one chapter per day. The first chapter appeared in print on Sunday.

“We talked about every possible way of doing this,” says Morning News editor in chief Mike Wilson, a veteran of what is now the Tampa Bay Times (who also, as CJR previously put it, “took part in the heyday of long-form literary journalism at The Miami Herald in the ’80s and ’90s.”) His team compared notes with other newsrooms who’ve published serial longform pieces, and Wilson says they learned that some outlets have seen a big dropoff in traffic to the story after the first day. They decided to experiment with interrupting the digital reading experience only once, at the end of the first chapter, with a prompt to register online by sharing an email address to get access to the rest of the story.

‘It’s a statement of our journalistic values,’ says Wilson. He hopes ‘My Aryan Princess’ will encourage more reporters to bring their editors rich, complex stories that only get better the deeper you dig.

Wilson says the strategy was prompted in part by the tremendous increase in subscriptions and other forms of engagement some papers have seen since the election and President Trump’s attacks on the press. “We wanted to capitalize on the growing sentiment out there that journalism is valuable and worthwhile,” he says.

Leona Allen, who co-edited “My Aryan Princess” with Wilson, says the paper’s publishing strategy appears to have paid off, noting that traffic metrics show that a significant portion of readers inhaled the entire story in one sitting. They’ve also seen better-than-expected engagement with an audio version of the story posted online, which has been downloaded over 4,000 times through the Morning News site.

“This is not something the Morning News does everyday,” says Allen, in terms of the depth of reporting as well as its digital presentation. She says bringing folks from photography, graphics, and other desks around the newsroom early on in the process was crucial to the success of the project. “Get buy-in as early as possible so people can start getting creative as early as possible,” she says.

This isn’t Farwell’s first foray into serial longform stories that take months to report. He was a Pulitzer finalist for his 2013 eight-part story of a young woman’s struggle to build a life after a childhood of horrific abuse. Since Wilson joined the paper in 2015, the Morning News has also published “The Long Way Home,” which follows one family trying to put the pieces back together after living in a homeless shelter for a year.

“The investment in stories like this” at the Morning News “is remarkable,” says Farwell. “I spent most of my career lusting after these sorts of stories, and the advice I would have for any reporter who thinks they have a story that needs more is simple really: keep going back.” Farwell says he called and wrote letters to sources involved with prosecuting the Aryan Brotherhood of Texas for nearly a year before getting a bite big enough to merit this intensive reporting. “Put your editors in a tough spot,” he says. “Make it tough for them to say no.”

At the end of the day, Morning News editor Mike Wilson says there’s no question this massive mobilization of resources was worth it. “It’s a statement of our journalistic values,” says Wilson. In fact, Wilson says he hopes “My Aryan Princess” will encourage more reporters in the newsroom to bring their editors rich, complex stories that only get better the deeper you dig. The paper has also expanded its investigative team under Wilson’s tenure. “Of course, the investment is shaped by the strength of the material,” he says. “We want our reporters—and our readers—to see that we are willing to make an investment in great stories, beyond what they can expect to find anywhere else.”

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.