Sign up for The Media Today, CJR’s daily newsletter.

“GOOD NEWS” HAS A BAD REPUTATION in the news business. Good news isn’t serious journalism, the thinking goes. Good news is soft, boring. People need journalism to tell them what’s wrong in the world so that they can set about making it right.

If that logic applies to anything at all, it certainly does not apply to coverage of disaster—something that journalists would do well to remember as they cover Hurricane Maria.

People affected by a disaster have urgent questions: Are my friends and family alright? Is my home in one piece? A “yes” to either of those questions is at least as newsworthy to the asker as a “no.” Yet disaster coverage—particularly on cable news—tends to focus on the bad to the exclusion of the good. To tell your audience that some people are not alright, and that some houses are not in one piece, is not enough.

ICYMI: The telling difference between captions for two Hurricane Katrina photos

Last week, my mother, father, niece, and sister-in-law, after fleeing their homes in the lower Florida Keys ahead of Hurricane Irma’s arrival, huddled around CNN.com in my living room in Georgia. (The Macon Telegraph interviewed them about their decision to evacuate.) Cable news, the most immediate source of information about the fate of their community, was pretty much only giving the bad news—which, by itself, didn’t tell them much about what they really wanted to know.

Here’s a particularly ridiculous example: CNN’s Bill Weir reported on-camera from the scene of a bar on Key Largo that had been leveled by Irma. “It’s all gone, it’s all gone,” he said in the breathless tones typical of his medium. “The storm surge shoved everything.”

Tweeting a video of Weir’s stand-up, CNN’s Meg Wagner wrote, “Storm annihilates bar in Key Largo: ‘It’s all gone.’”

Storm annihilates bar in Key Largo: "It's all gone." https://t.co/BXV1rwrzPv

— Meg Wagner (@megwagner) September 11, 2017

Both of those micro-reports are flawed, but that’s not even the most ridiculous part. As you can see in the video, the bar was not “all gone”—it was reduced to rubble. The most powerful hurricanes to ever hit the Florida Keys have been known to wipe islands clean of even the topsoil. The fact that most of this building’s pieces appeared to remain on-site was actually an indication that forecasters’ worst fears about Irma had not been realized.

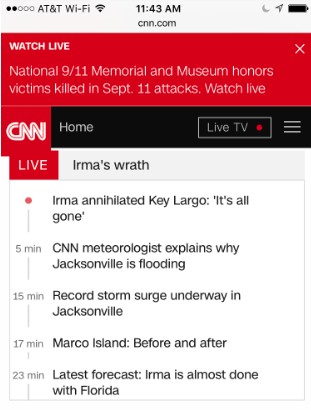

Here’s where it gets ridiculous: Based on Weir’s reporting on the destruction of a single structure on Key Largo, someone wrote the following CNN.com homepage headline: “Irma annihilated Key Largo: ‘It’s all gone.’”

Screenshot courtesy of Adam Ragusea

The whole 33-mile island is just “gone,” huh? Funny, I could see at least four or five structures in the background of Weir’s shot that seemed intact. Not surprisingly, local media offered a more nuanced assessment of the situation.

ICYMI: An interactive timeline of developments at Facebook

I’ll admit that this demonstrably false headline is an extreme example. And, as a journalist myself, I know there’s a good reason why people like Weir, Wagner, and me focus on bad news: The “bad” is what’s different, and what’s different is what’s news. Most days, most people can count on the sky not killing them or wiping out everything they own. That is the norm, and the norm is not news; it is the baseline. We report deviations from the norm, because the norm is otherwise assumed. (Likewise, I assume that CNN headlines are essentially accurate, which is why I consider this hugely overstated headline to be newsworthy.)

Cable news crews with satellite uplinks were the only eyes on the ground that my family had, and all those eyes ever seemed to look at were scenes of devastation.

Some journalists may also feel an obligation to help authorities impress upon people the seriousness of the situation so that they will flee or shelter accordingly. But in a situation like Irma, the fact that some buildings appear relatively unscathed is just as newsworthy as the destruction of others—at least, if one of those buildings is your home.

My family drove up I-75 to my house expecting that they might never see their own houses again. Most people they knew followed the evacuation orders as well; those who stayed quickly lost phone, power, and internet. Cable news crews with satellite uplinks were the only eyes on the ground that my family had, and all those eyes ever seemed to look at were scenes of devastation.

A few days later, NOAA uploaded aerial imagery showing that my family members’ houses, along with most others in the Keys, were—at the very least—still standing. If journalists want to better serve people affected by disasters, they should remember that sometimes a shot of an ordinary, intact streetscape can be the biggest news of all.

ICYMI: Reporting from “the most dangerous place to be a reporter in the entire Western Hemisphere”

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.