Sign up for The Media Today, CJR’s daily newsletter.

IN BUSTED, A 2014 BOOK based on their Pulitzer Prize-winning investigation of police corruption, Philadelphia Daily News reporters Wendy Ruderman and Barbara Laker offer ample anecdotal evidence of the distinctive jadedness and intense professionalism of their editor, Gar Joseph.

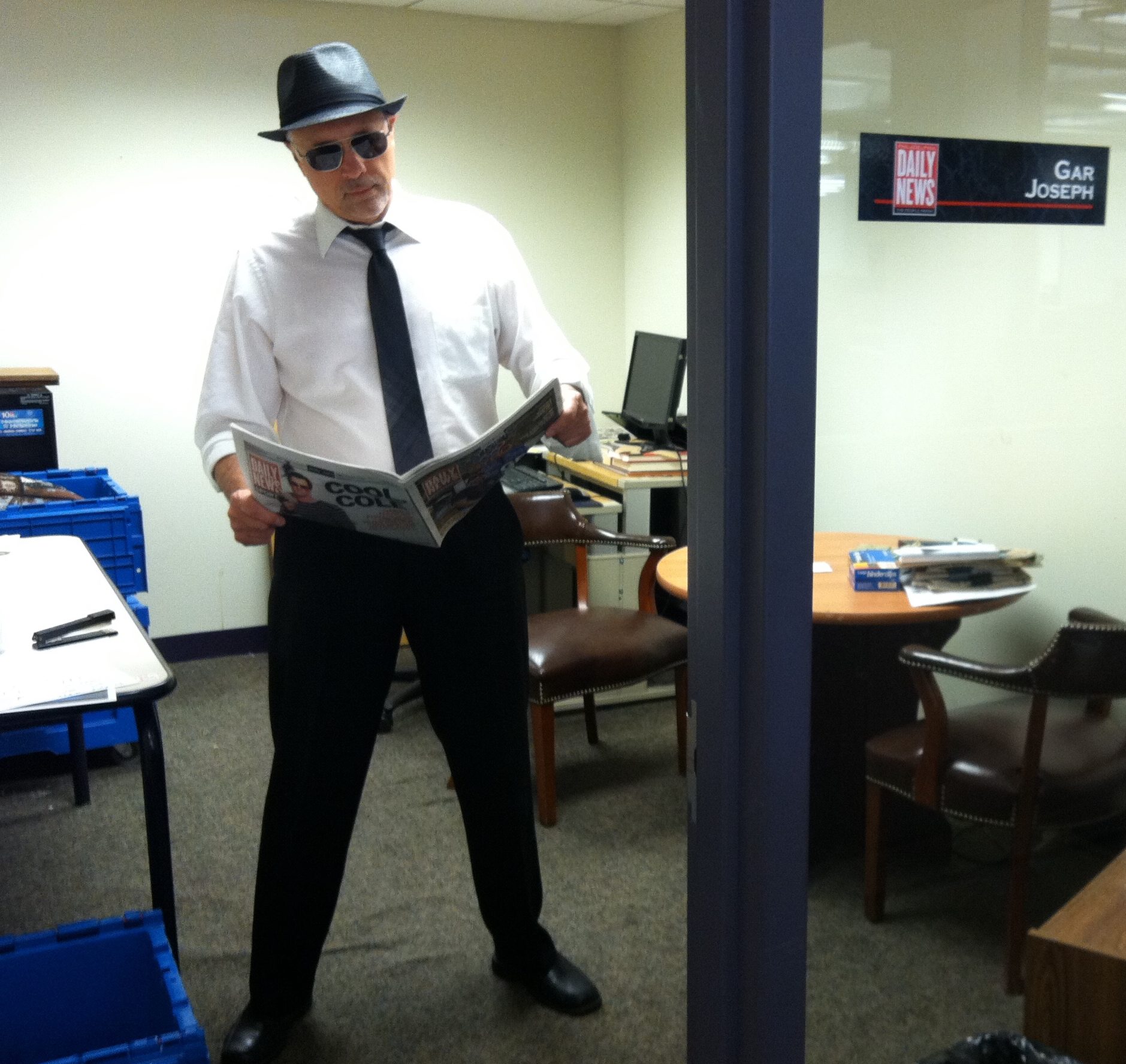

“Gar had declared our first version ‘a fucking mess,” write Ruderman and Laker about Joseph’s early response to their investigation. “He wasn’t the type of editor to tiptoe around reporters’ fragile egos. He got impatient, sometimes unapologetically rude, with reporters who couldn’t pitch a story idea in one sentence or less.’’ Joseph, who left the Daily News in 2015 after being diagnosed with a rare, fatal form of brain cancer, kept a poster in his cubby hole office that read: “Despair. It’s always darkest just before it goes pitch black.”

ICYMI: Two dozen freelance journalists told CJR the best outlets to pitch

Later in the book, however, another side of the 36-year veteran of Philadelphia’s combative print journalism world emerges. “Gar had a love-hate relationship with his job,” Ruderman and Laker write. They quote Joseph on the topic of his work: “It’s very manic-depressive. I’m either so fuckin’ depressed that I want to quit or I feel on top of the world because I’ve got a great story.”

They recount the time that Joseph disappeared into his office early one evening to edit the latest installment in their series. He didn’t emerge for a while, and they were nervous. Then came an email: “This might be the best story I’ve edited in my entire career.”

The Daily News was scrappy and sharply written, but had never won a reporting Pulitzer in its turbulent 90-year history until Ruderman, Laker and Joseph came along.

IT’S HARD TO OVERSTATE Joseph’s impact as an editor, just as it’s hard to overstate the significance of editors like Joseph to their newsrooms and their cities. Joseph’s passion for his highly competitive profession largely defined his life; he was a “newspaperman,” a dated designation that invokes a journalistic world eclipsed by the digital era. If journalism’s practices and platforms have evolved, then one hopes there are still editors with Joseph’s tenacity at work behind the stories produced by American newsrooms.

Print’s journalistic hegemony faded significantly during Joseph’s time at the Daily News. The stylish and feisty tabloid was a study in financial fragility long before the digital revolution began to jeopardize print’s foundations: The paper barely survived the Depression, and over the years several owners threatened to kill it unless unions agreed to staff and pay cuts. In the past 60 years, the Daily News has had seven owners, including five during a nine-year stretch of digitally related upheaval. Its newsroom merged with those of the Philadelphia Inquirer and Philly.com in 2015.

Joseph’s career spanned decades of competition between the Daily News and the Inquirer, which won Pulitzer after Pulitzer during the 18-year reign of revered editor Gene Roberts. The Daily News was scrappy and sharply written, but outmanned and frequently outclassed. It had never won a reporting Pulitzer in its turbulent 90-year history until Ruderman, Laker and Joseph came along. (The paper’s previous two Pulitzers were for editorial writing in 1985 and editorial cartooning in 2014.)

Joseph grew up in a blue-collar family in northern New Jersey – he was born in Paterson – and read the New York Daily News from age 12. In 1965, Joseph graduated from Midland Park High School and moved to Warrensburg, Missouri, where he attended college and became the first in his family to receive a degree.

Joseph began his time in print with a brief reporting stint at the Sedalia Democrat in Missouri. From ’71 to ’75, he was a reporter at the Kansas City Star, then theAsbury Park Press. After working for three years as assistant metro editor at the Wilmington News Journal, he joined the Daily News in August 1981.

Joseph, left, in 2013, with Wendy Ruderman and Barbara Laker, the reporters behind the Philadelphia Daily News’ Pulitzer Prize-winning investigation of police corruption in the city. Photo courtesy of Gar Joseph.

IN PHILADELPHIA, Joseph was thrown into the fire fast. Two major strikes—in the Philadelphia public schools and the metropolitan area transit system—required strong, savvy reporters like Joseph to compete against the Pulitzer-chasing shock troops of the Inquirer. Joseph remained a reporter until 1985, when he moved up to assistant city editor, and then to city editor in 2001.

His tenure in that job was the longest in the paper’s history, and included his work on the Pulitzer-winning project that defined and validated—perhaps even vindicated—his career. When his brain tumor forced him into retirement in 2015, at age 68, Joseph was assistant managing editor.

“My head said what I wanted to say, but my mouth wouldn’t say it,” Joseph said. At the hospital, someone held a pen in front of Joseph, “and I couldn’t say what it was.”

JOSEPH IS ABOUT AS DAPPER a 69-year-old cancer patient/retired editor as you’ll find. We met for lunch in late May, and sat together in a booth near the back of a Philadelphia diner. Joseph wore his trademark gray fedora to cover his partially shaved head; his minimalist gray beard was carefully trimmed. In a raspy voice, he summarized his own story with an editor’s precision: “Thank God the brain cancer waited for the Pulitzer.”

That cancer—glioblastoma, a one-in-10-million shot, Joseph said—didn’t assert itself dramatically until five years after the Pulitzer. Joseph said he’d had occasional memory problems before while editing, but attributed them to aging; there was no cancer of any kind in his family. Then, on a September day in 2015, while editing a Ruderman story, Joseph suddenly couldn’t speak. “My head said what I wanted to say, but my mouth wouldn’t say it,” Joseph said.

At the hospital, someone held a pen in front of Joseph, “and I couldn’t say what it was,” he explained. The initial tentative diagnosis was a stroke, but x-rays revealed a large growth at the top of his brain. “Worse than a stroke,” Joseph said—a catastrophic, career-ending illness.

TRENDING: Headlines editors probably wish they could take back

“I was one of the biggest losers,” said Joseph about his medical odds, “but a total winner as an editor toward the end of my career.” This September, Joseph will reach the average survival level for someone his age with his diagnosis: 24 months. If he can beat the odds for an additional six months, then he’ll have a 50 percent chance of survival year after year.

For now, Joseph is planning a trip to Tuscany with his wife, Martha Woodall, a long-time Inquirer reporter. “It’s the kind of thing I won’t pass up,” Joseph said.

IN 2014, JOSEPH, RUDERMAN AND LAKER seemed on the verge of a journalistic trifecta: Pulitzer, book, and a TV series. A production company, Sidney Kimmel Entertainment, bought the rights to Busted. David Frankel, who directed The Devil Wears Prada and who is the son of former New York Times editor Max Frankel, was positioned to direct. Sarah Jessica Parker expressed an interest in the project. Parker visited Philadelphia and had lunch with the two reporters and Joseph, who all found her likeable. “Not snotty or pretentious at all,” Joseph said.

But Parker eventually had to withdraw from the project because of a commitment to an HBO series. Since then, Busted has been in development limbo, although Ruderman said she and Laker still have a contractual agreement with the production company. “We get checks,” said Ruderman.

The production company “has the money to make the show,” Ruderman added. “I don’t think it’s dead in the water.” A spokesperson for the company said, “Nothing is happening. Development takes a lot of time.”

Speaking about the possible series, Joseph said, “I hope I’m still alive, but when it will happen I don’t know.” Ruderman shared her editor’s hope in the face of uncertainty. “It would be horrible if Gar didn’t live to see the film,” she said. “I want to pass the popcorn to him.”

ICYMI: The surprise 2017 Pulitzer winner

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.