Sign up for The Media Today, CJR’s daily newsletter.

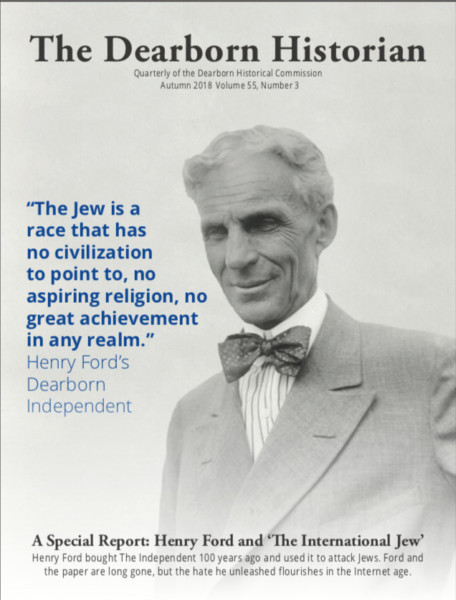

One hundred years ago, Henry Ford bought a newspaper in Dearborn, Michigan, and used it to publish an anti-Semitic 91-part series called “The International Jew.” The centennial for Ford’s stint as a media mogul cued a local magazine to put together an 11-page package that re-examined Ford’s bigotry and traced its influence to modern-day white nationalist media forums.

But before it could reach readers, Dearborn’s mayor censored the magazine and then fired the editor.

ICYMI: Headlines editors probably wish they could take back

“100 Years Later, Dearborn Confronts the Hate of Hometown Hero Henry Ford” was slated as the cover story of The Dearborn Historian, a quarterly published by a historical commission appointed by the mayor. It has no online presence and its subscriber list includes about 230 museum members. A courtesy copy of the newly printed issue was delivered to Mayor John “Jack” O’Reilly in late January.

O’Reilly first disputed an incendiary quote from Ford’s newspaper, the Dearborn Independent, that appeared on the cover of the Historian alongside a portrait of Ford. The magazine was reprinted with a new cover that removed the quote. Then on January 28, the mayor ordered that it not be distributed at all, with or without the quote.

The planned cover for the Autumn 2018 issue of The Dearborn Historian, which has not been distributed.

“We want Dearborn to be understood as it is today—a community that works hard at fostering positive relationships within our city and beyond,” according to part of a statement by Dearborn’s public information officer that was delivered on Friday afternoon in response to CJR’s request for comment. “We expect city-funded publications like The Historian to support these efforts. It was thought that by presenting information from 100 years ago that included hateful messages—without a compelling reason directly linked to events in Dearborn today—this edition of The Historian could become a distraction from our continuing messages of inclusion and respect. For this reason, the Mayor asked that the distribution of the hard copies of the current edition of The Historian be halted.”

Bill McGraw, the part-time editor of the Historian, said that he received a phone call from the museum’s chief curator, the liaison to the mayor, on Thursday afternoon and learned that he’d be removed from his position. The move came after news of the mayor’s action broke on an online news site, Deadline Detroit, which also ran his full article. McGraw co-founded the site in 2012 with Allan Lengel, who, as it happens, is the son of a Holocaust survivor. While McGraw is no longer involved with its day-to-day operations, he had long planned to run his Ford article there, with credits to the Historian. He thought this would be a way to bring in a wider readership.

The first thing I thought of, and I’m not kidding, is that January was the anniversary of Henry Ford buying the Independent…I was thinking of this issue from day one, literally.

By effectively pulping the magazine—as far as McGraw knows, the hard copies are still at the print shop—the story has gotten even more attention than expected. McGraw said he knew this would happen, as did David Good, his predecessor and a former Detroit News editor.

“We begged them, myself and David Good, we literally begged the curator of the museum, ‘Don’t mess with this because it will blow up in your face,’” McGraw says. “We literally were almost on our knees. We knew what would happen, but he didn’t get it. The two people who spent their lives in journalism knew.”

McGraw received the call about his job hours before an emergency meeting of the historic commission (where he says he intended to resign anyway). At the meeting, the commission passed a resolution that reads:

The Dearborn Historical Commission endorses the efforts of the editor of the Dearborn Historian, in the best traditions of journalistic integrity and historical accuracy, to analyze and report on significant events from the City’s past, even when the publication of such reporting may not reflect favorably on actions taken by local institutions or individuals, including City officials. The Commission further expresses its strong objection to efforts to stop publication of such reporting – as exemplified by Bill McGraw’s “Henry Ford and The International Jew.”

The Dearborn Historical Commission, in an effort to save the city’s current reputation as a community open to all without concern for ethnicity, strongly recommends that Mayor Jack O’Reilly, Jr. direct Jack Tate to release the most current issue of the Dearborn Historian.

The city, meanwhile, says in its statement that “the Mayor did not ‘fire’ Mr. McGraw.” It points to the contractor status of the role and puts the onus on the historical museum’s chief curator, who is the one who called McGraw to tell him the news, for “the decision to terminate the contract.”

McGraw is an esteemed Detroit journalist who has been inducted into the state’s Journalism Hall of Fame. He wrote for the Detroit Free Press for 37 years and reported for Bridge Magazine, a nonprofit news outlet. He also produced and co-wrote the documentary “12th and Clairmount” about the 1967 uprising. (Disclosure: McGraw and I are acquainted and he once wrote me a letter of recommendation for a journalism fellowship, but we have not worked together.)

McGraw has also been a Dearborn resident for more than 30 years. When he was asked to edit the historical magazine this summer—“the perfect retirement gig,” he said—he knew he had an opportunity to examine the reach of Ford’s anti-Semitism. “The first thing I thought of, and I’m not kidding, is that January was the anniversary of Henry Ford buying the Independent…I was thinking of this issue from day one, literally.”

When Henry Ford died in 1947, his industrial innovations like the assembly line and the $5-a-day wage were praised not only for turning his namesake auto company into a global behemoth but for ensuring an Allied victory in World War II. It wasn’t until the 39th paragraph of the Associated Press’s obituary of Ford that his tenure as the publisher of the Independent was mentioned, along with his role in the spread of anti-Jewish hate.

‘I was totally blown away by how active Ford is’ in online white supremacist forums, McGraw says.

For two straight years, every issue of the Independent attacked Jewish people with, among other things, stereotypes about financial control. With Ford’s power and money, it had a big influence. Ford auto dealers were compelled to run subscription campaigns, which helped the Independent’s circulation to reach 900,000. That made it “one of the biggest periodicals in the country,” according to McGraw.

“Showing the marketing expertise that had catapulted Ford Motor into one of the world’s most famous brands,” McGraw wrote in his article, “Henry Ford’s lieutenants vastly widened the reach of his attacks by packaging the paper’s anti-Semitic content into four books.” They were translated into 12 languages and distributed across Europe and North America in the years before World War II, where they “influenced some of the future rulers of Nazi Germany.”

Hitler himself spoke to a Detroit News reporter in Munich in 1931 from an office that featured a large portrait of Ford. As McGraw recounts, “I regard Henry Ford as my inspiration,” Hitler said.

The paper’s recurring anti-Semitic coverage prompted protests, a boycott, a lawsuit, Ford’s lukewarm apology, and its closure in 1927. The Ford company has since renounced those views and affirmatively supported a number of Jewish causes. But copies of the “The International Jew” were distributed long after, and McGraw ties Ford’s legacy to the present-day hate that has been exposed in Charlottesville, Pittsburgh, and beyond.

“I was totally blown away by how active Ford is” in online white supremacist forums, McGraw says. The industrialist is mentioned “hundreds of thousands of times.” McGraw noticed that people who appeared to be “new to the movement” were encouraged by Ford’s status, which they saw as giving legitimacy to their views. “‘Hey, look at this incredible American, this global celebrity: he thinks like us,’” is how McGraw summarizes the posts.

Dearborn is still home to Ford Motor Company, but the city of nearly 100,000 people also has the nation’s largest proportion of Arab Americans and is adjacent to the biggest mosque in North America. Its African American community is also steadily growing. In 2017, Mayor Jack O’Reilly was re-elected to his fourth term with 57 percent of the vote. Under his leadership, a statue of Orville Hubbard, an arch-segregationist who served as mayor from 1942 to 1978, was removed from the grounds of city hall and put in a less conspicuous place, with signage that contextualizes is discriminatory policies.

But Ford’s flaws are still a prickly point for the city. Good, the former Detroit News editor who ran the Historian for seven years, recalls that he was largely given a free hand with the magazine—except one time, about two years ago, when he was set to run a package about Ford’s long-rumored illegitimate son, cued by a new book that examined the story. Good says that word of the magazine’s forthcoming feature somehow made it to Edsel Ford II, Henry’s great-grandson, who, Good was told, made a few phone calls that “threatened legal action and financial repercussions” if it ran.

“I was told we would hold off on doing this package,” Good says, until the heat “quieted down.” The piece has never run. McGraw, who was recruited by Good, took over the editorship last summer.

Ford’s anti-Semitism is not exactly breaking news, although McGraw’s article brings a big spotlight and a wealth of detail to the story—much of it researched from the robust collection at Dearborn’s Henry Ford Centennial Library. So, “yes,” McGraw says, “the strength, the velocity, the amplitude of the reaction was really surprising. I thought maybe there’d be a little blowback,” like a request to get a heads up when stories like this are coming. And indeed, three times over the previous fall, he was truthful when asked what he was working on—though he wasn’t asked for details, and he didn’t offer them.

ICYMI: Massive layoffs hit news outlets: BuzzFeed, HuffPost, and more

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.