Sign up for The Media Today, CJR’s daily newsletter.

I’ve lately been losing myself in The New York Times archives, scrolling through front-page coverage of World War II. Days with no landmark battles, such as January 23, 1943—when, as the paper reported top-right, Allies made progress in Kharkov and Tripoli, but the Nazis built two U-boats for every one the Allies sank. Center bottom, as always: “War News Summarized.” Below the fold, a Netherlands crown princess gave birth on “Dutch soil” in safe Ottawa. The pages portray a United States facing down an existential threat. On such days, even gossip stories were stories about the war.

Today, the climate crisis is no less an existential threat. To limit the worst effects of the climate crisis, we have under eleven years to decarbonize our economy, mobilizing, as Bill McKibben and others have urged, on the speed and scale of WWII. One might expect to see that mobilization effort in the US media more often; climate change, after all, frames every beat. A threat of such breadth, teen climate activist Greta Thunberg once said, should preclude us from talking, writing, or reporting about anything else.

ICYMI: Transforming the media’s coverage of the climate crisis

Yet my news feed tells a different story. Scrolling through my Apple news feed on a Sunday in April, climate coverage was hard to come by. I saw stories about a rabbi shot at the Poway synagogue, who had delivered an inspiring sermon; Trump rallying supporters with calls of “fake news”; and a teen whose hepatitis may have been induced by green tea. Other top stories included a piano prodigy turned viral sensation and an American tourist charged with killing a Dominican national in Anguilla. The “Science Section” led with UFOs from The Atlantic, followed by the oldest tree, dark matter, the FCC’s SpaceX plans, wondrous volcanos, someone eating a live rattlesnake, and research indicating the world is sadder and angrier than ever before. At last, I hit a climate piece, from Wired: a story on plants genetically modified to absorb more carbon dioxide.

I repeated the exercise with the Times’s news app: three articles on Biden’s run, Barr’s Congressional testimony, the Sri Lanka Easter attacks, the California synagogue shooting, and, finally, a three-day-old story, “Can Humans Help Trees Outrun Climate Change?” To be fair, the Times had that week run an ambitious slate of climate stories around Earth Day, as well as a climate-themed issue of its magazine.

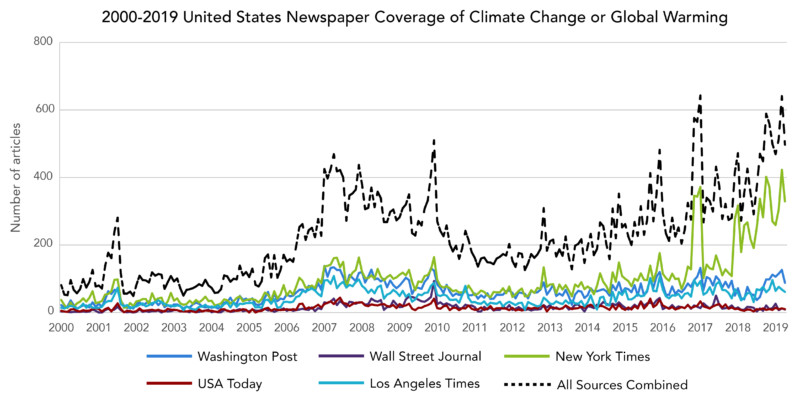

In fact, the Times leads US popular newspapers in climate coverage, at arguably our best climate-coverage moment ever. A recent study of five major US newspapers counted more climate stories in March 2019 than almost any month since 2000. Of those stories, more than half—a grand total of 423—came from the Times.

Image courtesy of CIRES Center for Science and Technology Policy Research, University of Colorado Boulder

Still, there’s a widespread sense that, per a recent headline from The Guardian, “the media is failing on climate change.” When it comes to an existential crisis, what does sufficient coverage look like?

While many leading climate journalists concur newsrooms are not covering climate enough, several told CJR that more climate stories does not necessarily equate to quality coverage. “Growth is not measured in the number of stories, but in the kind of stories we tell,” Hannah Fairfield, the Times’s climate editor, says. We need creative, personalized stories that engage readers, which might depend in part on form. Fairfield, who has a background in data visualization, says she works to tell stories in phone-friendly ways that are “new and creative and form-changing.” Such efforts by the Times include striking visual pieces showing Yellowstone’s climate-wrought changes, and solutions-oriented coverage of Costa Rica’s Green New Deal.

And, if we are keeping score, then some stories certainly win more points with readers. The Times climate desk’s top-read story last year was an interactive feature that invited readers to learn how many more days of extreme heat their hometowns experience now, compared to their birth year, which drew readers to look up data from more than 18,615 cities and towns. Last August, the New York Times Magazine devoted an entire issue to a 30,000-word recent climate history by Nathaniel Rich that he adapted into his dramatic book, Losing Earth.

Rich, while calling for more climate coverage, raises a conceptual problem he sees with fixating on frequency. Climate change “shouldn’t be thought of as one item on the menu of issues discussed by the press” such as healthcare or immigration, he says, but rather as “a framework for how we understand all of them,” likening climate change to a “connective tissue” and “the fabric of our life.” There should be an understanding, he says, that you can’t write about all of these other issues—and extreme weather, in particular—without mentioning climate change. He calls the failure to interweave climate into general coverage “one of the failures of our time.”

Similarly Sara Peach, Senior Editor at Yale Climate Connections, says that climate change needs to “be infused across all the beats.” As a thought experiment, she asks, what if reporters were tasked with covering a change not to climate but to gravity, another force that sets the terms of reality? The dearth of climate stories—and, beyond that, climate change’s unacknowledged role in stories on immigration, healthcare, and weather—signals, in part, a news media at odds with reality.

We didn’t fight WWII purely out of hope and optimism, we fought it because we were really scared… If we really need that type of mobilization now, I suspect we’ll need messaging that draws on fear at least as readily.

In 1943, everyone agreed the war was a real, immediate, universal threat that demanded front-page coverage. In today’s scattered media landscape, there is no ready equivalent to Page One, and the existential threat we face doesn’t always feel so immediate or intertwined with our daily lives, even to readers who don’t doubt climate change’s reality. “We’re not where we need to be with climate journalism, but we’re not where we need to be with climate policy, either,” David Wallace-Wells, New York Magazine’s deputy editor, and author of The Uninhabitable Earth, says. While journalism is a public service, Wallace-Wells says, “it’s also a business, and it’s also a leisure activity for most of the readers that consume it.” The same media that shape public understanding of climate’s pervasive reach also cover movie openings, the NCAA tournament, and Meghan Markle.

Still, we can learn from the coverage of WWII. We must do our best to make climate change the mainstream news’ central narrative by making the connections Rich and Peach describe. Practically speaking, reporters should ask whether their beat is affected by climate change, veteran environmental reporter and Editor of Yale Climate Connections Bud Ward says. “When it’s a yes— and I really think virtually every beat gets to a yes pretty easily— they should consider whether climate change is a worthwhile angle in that story.” This doesn’t mean climate needs to be in every story, Ward clarifies—“just that it should run through reporters’ and editors’ minds.”

We need to make sure that climate change coverage is everywhere. News outlets must find ways serve local news deserts, David Sassoon, founder and publisher of the Pulitzer Prize-winning InsideClimate News, says. InsideClimate News now leads a National Environment Reporting Network, supporting local reporters to “engage their own audiences at a local level, free of the national polarization.” They recently published a series on climate solutions for the Midwest, the fruits of a collaboration by 14 newsrooms. Elsewhere, Yale Climate Connections’ short radio segments appear on nearly 500 mostly public radio frequencies.

Some publications may rewrite their very identities, asking tough questions about journalism’s essential role. In 2015, as then editor-in-chief Alan Rusbridger prepared to leave The Guardian, he rallied his team to revolutionize climate reporting, leading the paper to spearhead a fossil-fuel divestment campaign, “Keep it in the Ground,” and report on this fraught process in a podcast, The Biggest Story in the World. Such foundational changes continue today: recently, aligned with the call of activist group 350.org and others, The Guardian replaced the term “climate change” with “climate crisis or emergency or breakdown” in their house style guide.

“We want to ensure that we are being scientifically precise, while also communicating clearly with readers on this very important issue,” editor-in-chief Katharine Viner said in a story announcing the change. “The phrase ‘climate change’, for example, sounds rather passive and gentle when what scientists are talking about is a catastrophe for humanity.”

There is a longtime convention among climate scientists and communicators that panic is counterproductive. But Wallace-Wells, who wrote a New York Times op-ed called “Time to Panic,” says, “We didn’t fight WWII purely out of hope and optimism, we fought it because we were really scared… If we really need that type of mobilization now, I suspect we’ll need messaging that draws on fear at least as readily.”

Should the tenor of our climate coverage always recall the Battle of Midway? “The climate desk isn’t urging readers to panic,” Fairfield says. Instead, for readers, “our focus is to bring revelation and surprise.”

The bigger point, journalists say, is that climate stories require a range of tenors and narrative modes, given its complex reality. Both Wallace-Wells and Rich attribute their books’ success, in part, to what Wallace-Wells calls “storytelling opportunities left on the table.”

And, as with the Times’ front-page war coverage, the climate crisis should always be emphasized in prominent places. Along with its recent terminology changes, The Guardian started running daily atmospheric carbon-dioxide concentrations, which recently hit a record 415 parts per million, on their weather page. At least one reader told the paper that such information belonged front-and-center:

“It’s great that the Guardian will publish a daily record of carbon dioxide levels, but the place for this is not the weather page,” the reader wrote. However, “weather is outside our control. Carbon dioxide levels are our responsibility—the inexorable rise should be (daily) front-page news.”

NEW: Will Michael Wolff’s Siege stand the test of time?

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.