Sign up for The Media Today, CJR’s daily newsletter.

Researchers analyzing media coverage of medications that treat opioid addiction find inaccurate and negatively slanted coverage, especially in states with high mortality rates for overdose.

When the nation’s health is in peril, journalists play a vital role as reliable communicators of life-saving information. But when it comes to covering a public health emergency as complex and intractable as overdose deaths, a new study published in Health Affairs shows, journalists aren’t always reliable messengers.

Researchers at Johns Hopkins University and the University of Minnesota coded 300 news clips and broadcasts published between 2007 and 2016 for accurate and inaccurate messages about FDA-approved medications used to treat opioid use disorder: methadone, buprenorphine, and naltrexone. The sample comprises 171 local news clips from states that had high overdose mortality rates during the study’s time window, such as New Hampshire and Ohio, and 129 clips from national outlets such as the Wall Street Journal and The New York Times, as well as broadcast transcripts ranging from PBS to Fox News.

Related: A dangerous fentanyl myth lives on

Before diving into the study’s results, it’s important to review the science about the medications in question. Medications do a better job at keeping people engaged in treatment than traditional abstinence-based approaches that rely on group therapy, counseling, and the 12 Steps.

Most relevant to the current overdose emergency, methadone and buprenorphine, in particular, reduce one’s risk of fatal overdose by more than 50 percent. Both drugs are considered the “gold standard of care” in the scientific literature, and the World Health Organization lists them as “essential medicines.”

Drugs that so drastically improve survival rates for any other illness would be hailed as a medical miracle. But addiction occupies a bifurcated category of “disease”; it is simultaneously medicalized and criminalized. This duality is apparent in whether news describes the medicine as effective treatments or, per a 2013 New York Times article, another form of “dope.”

While the research is unequivocal, media coverage is a mixed bag. The Health Affairs study found that only a quarter of the 300 news stories sampled describe medications such as methadone and buprenorphine as effective. Their efficacy was curiously absent from coverage, as was the fact of their vast underutilization. Fewer than 40 percent of the articles reviewed made any mention of these medications being inaccessible and under-prescribed, while just four percent of articles identified stigma as a barrier to access.

“As an addiction medicine physician, I would say that stigma and persistent misunderstanding about the role of medication for opioid use disorder is one of the biggest, if not the single greatest, barriers to ensuring people have access to these treatments,” Dr. Sarah Wakeman, medical director at Havard’s Mass General Hospital Substance Use Disorder Initiative, tells CJR.

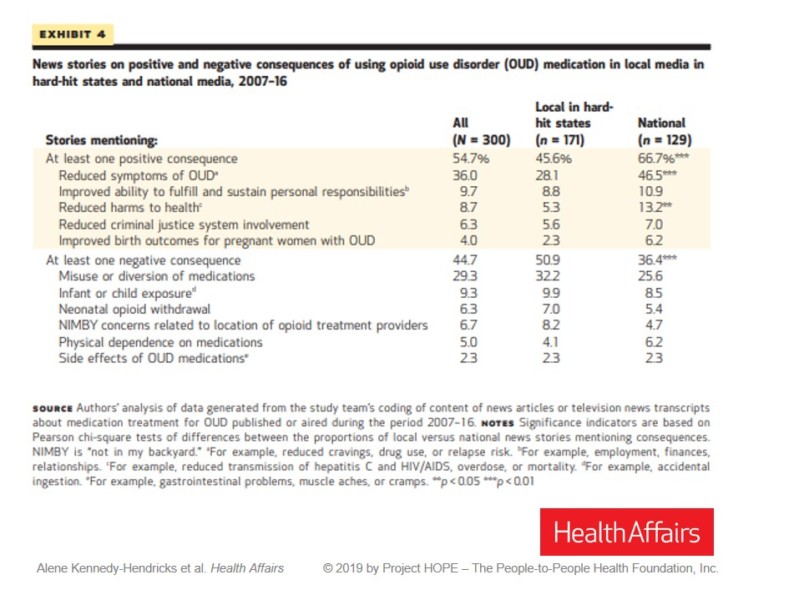

The study found that negative coverage was more common among local news outlets in states with high overdose rates than among national outlets. Of the 171 local news articles sampled, 51 percent mentioned at least one negative consequence of using these drugs, whereas 36 percent of the 129 national articles mentioned negative consequences. Every drug, of course, has side effects, which ought to be reported. But because drug use is criminalized, “negative consequences” are framed as a matter of breaking the law instead of, say, constipation. The most frequently invoked negative consequence, “diversion” to the black market, appeared in 32 percent of local news clips and 25 percent of national clips.

Courtesy of Health Affairs

For issues such as diversion, reporters with a more nuanced perspective can avoid misplaced fears and false equivalence. For example, the research about buprenorphine diversion finds “the most frequently cited reasons for non-prescription use were consistent with therapeutic use.” People seeking out the illicit market for a drug such as buprenorphine are trying to relieve painful withdrawal symptoms rather than “get high.”

When reporters focus on negative consequences, they often step into the realm of misinformation. The most frequently invoked inaccurate message about methadone and buprenorphine is the mistaken belief that patients who use them over long periods of time are addicted. A 2016 New York Times opinion piece with the headline “Addicted to a Treatment for Addiction” precisely captures this inaccurate message. A Times spokesperson tells CJR its coverage of treatments for opioid addiction “has been thorough, comprehensive, and fair,” and directed CJR to “The Treatment Gap,” a more recent series whose concerns include treatment access. Beth Macy, the author of the 2016 Times opinion piece, tells CJR she did not write its headline.

Macy, the best-selling author of Dopesick, worked for decades at The Roanoke Times in Virginia. Such midsized news outlets, faced with difficult budgetary constraints, devote fewer resources to covering rural areas like those Macy has reported on. Harried reporters risk uncritically quoting public officials, from law enforcement to judges to prosecutors, who believe that medication treatments amount to “substituting one drug for another,” Macy says.

Alene Kennedy-Hendricks, lead author of the Health Affairs study and a policy researcher at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, expected the “substituting one addiction for another” concept might appear more frequently than it did. “It appeared in 9 percent of stories, so that was somewhat reassuring,” she says. “It still appeared in more stories than its accurate counterpart–that people getting treated with these medications are not ‘addicted’ to them–so that is less reassuring.” Kennedy-Hendricks notes that this common trope is ideological, and not informed by the science.

Why local news played up negative consequences more often than national news was beyond the scope of the study. “It may be that certain issues like diversion of these medications are more likely to appear in local newspapers covering local crime,” Kennedy-Hendricks says. “Or that NIMBY issues related to medication treatment providers are more likely to appear in local news stories.”

Kennedy-Hendricks also suggests that unlike national outlets, local papers lack the capacity to assign health and science reporters to the opioid beat, which would enable them to develop the nuance and expertise necessary to navigate the minefield of addiction medicine.

Science journalist Maia Szalavitz, who has written about opioid coverage for CJR, says, “While this study accurately portrays some of the media failure regarding these medications, I think it misses how often these stories don’t adequately explain why and how the they work, which leaves the public vulnerable to misunderstanding.”

Dr. Alister Martin, one of Dr. Wakeman’s colleagues at Mass General, leads the “#GetWaivered” campaign aimed at getting more doctors to prescribe buprenorphine. While he’s focused on getting more doctors to step up and play their role, Dr. Martin says that the media has to do better, too.

“The data is clear,” he says. “Medications for addiction treatment save lives and as long as we continue to make it harder for patients to get help than it is to get high, we’ll struggle to overcome this crisis.”

ICYMI: An anti-transparency editorial in The Washington Post

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.