The influence of social media platforms and technology companies is having a greater effect on American journalism than even the shift from print to digital. There is a rapid takeover of traditional publishers’ roles by companies including Facebook, Snapchat, Google, and Twitter that shows no sign of slowing, and which raises serious questions over how the costs of journalism will be supported. These companies have evolved beyond their role as distribution channels, and now control what audiences see and who gets paid for their attention, and even what format and type of journalism flourishes.

Publishers are continuing to push more of their journalism to third-party platforms despite no guarantee of consistent return on investment. Publishing is no longer the core activity of certain journalism organizations. This trend will continue as news companies give up more of the traditional functions of publishers.

This report, part of an ongoing study by the Tow Center for Digital Journalism at Columbia Journalism School, charts the convergence between journalism and platform companies. In the span of 20 years, journalism has experienced three significant changes in business and distribution models: the switch from analog to digital, the rise of the social web, and now the dominance of mobile. This last phase has seen large technology companies dominate the markets for attention and advertising and has forced news organizations to rethink their processes and structures.

Findings

- Technology platforms have become publishers in a short space of time, leaving news organizations confused about their own future. If the speed of convergence continues, more news organizations are likely to cease publishing—distributing, hosting, and monetizing—as a core activity.

- Competition among platforms to release products for publishers is helping newsrooms reach larger audiences than ever before. But the advantages of each platform are difficult to assess, and the return on investment is inadequate. The loss of branding, the lack of audience data, and the migration of advertising revenue remain key concerns for publishers.

- The influence of social platforms shapes the journalism itself. By offering incentives to news organizations for particular types of content, such as live video, or by dictating publisher activity through design standards, the platforms are explicitly editorial.

- The “fake news” revelations of the 2016 election have forced social platforms to take greater responsibility for publishing decisions. However, this is a distraction from the larger issue that the structure and the economics of social platforms incentivize the spread of low-quality content over high-quality material. Journalism with high civic value—journalism that investigates power, or reaches underserved and local communities—is discriminated against by a system that favors scale and shareability.

- Platforms rely on algorithms to sort and target content. They have not wanted to invest in human editing, to avoid both cost and the perception that humans would be biased. However, the nuances of journalism require editorial judgment, so platforms will need to reconsider their approach.

- Greater transparency and accountability are required from platform companies. While news might reach more people than ever before, for the first time, the audience has no way of knowing how or why it reaches them, how data collected about them is used, or how their online behavior is being manipulated. And publishers are producing more content than ever, without knowing who it is reaching or how—they are at the mercy of the algorithm.

In the wake of the election, we have an immediate opportunity to turn the attention focused on tech power and journalism into action. Until recently, the default position of platforms (and notably Facebook) has been to avoid the expensive responsibilities and liabilities of being publishers. The platform companies, led by Facebook and Google, have been proactive in starting initiatives focused on improving the news environment and issues of news literacy. However, more structural questions remain unaddressed.

If news organizations are to remain autonomous entities in the future, there will have to be a reversal in information consumption trends and advertising expenditure or a significant transfer of wealth from technology companies and advertisers. Some publishers are seeing a “Trump Bump” with subscriptions and donations rising post-election, and there is evidence of renewed efforts of both large and niche publishers to build audiences and revenue streams away from the intermediary platform businesses. However, it is too soon to tell if this represents a systemic change rather than a cyclical ripple.

News organizations face a critical dilemma. Should they continue the costly business of maintaining their own publishing infrastructure, with smaller audiences but complete control over revenue, brand, and audience data? Or, should they cede control over user data and advertising in exchange for the significant audience growth offered by Facebook or other platforms? We describe how publishers are managing these trade-offs through content analysis and interviews.

While the spread of misinformation online became a global story this year, we see it as a proxy for much wider issues about the commercialization and private control of the public sphere.

Click here for a PDF of the full report.

Introduction: Watermelons to Democracy

They are publishers. They control the audience in many ways . . . They’re the gateway to the audience, and they determine what they will allow and what they won’t. It’s their world.

—Kim Lau, Senior Vice President & Head of Business Development of The Atlantic

In April 2016, on a windswept pier in San Francisco, thousands of engineers and executives crowded into the Fort Mason conference center to attend the annual Facebook developer conference. In the Media Track theater there was not a spare seat available. Media executives from America and around the world crammed into the aisles, hoping to hear how Facebook would help them make money from their content.

On stage Jonah Peretti, the founder of BuzzFeed, and Chris Cox, the co-founder of Facebook and the company’s head of product, discussed the best examples of “what works” on the social web. The answer, it turned out, was two BuzzFeed employees placing rubber bands around a watermelon until it exploded on Facebook Live video. At its peak, the watermelon experiment had a live audience of 807,000 simultaneous views. This was presented as a new opportunity for publishers to be enriched by a Facebook innovation. Many in the room likely felt empathy with the watermelon, as their businesses were being squeezed slowly to the point of implosion by external forces beyond their control. One of those forces is Facebook itself.

Seven months later, it was more than watermelons that had exploded all over Facebook. A week after the widely unexpected result of the 2016 US presidential election, BuzzFeed Media Editor Craig Silverman broke a series of stories exposing how misleading news had spread across social media during the election cycle, primarily on Facebook. Websites producing fake stories on an industrial scale were popping up from California to Macedonia. Silverman’s reporting demonstrated that in the months leading up to the 2016 election, the number of likes and shares for posts from sites such as Freedom Daily, on which almost half the content is false or misleading, was on average nearly 19 times higher than for posts from a mainstream news outlet such as CNN.

In the horror movie of journalism’s disappearing business models, the fake news scandal was the equivalent of the phone ringing from inside the house. The hope was that the convergence of social media and journalism would create a superior version or hybrid of both; a rich network populated by useful and timely information, which could be easily augmented, shared, and commented on by a highly engaged population. Instead, the worst elements of both worlds have combined, tainting the old media and the new.

The unchecked viral spread of untrue, exaggerated, and wildly partisan pieces is forcing a long overdue debate about the rights and responsibilities of both news organizations and social media platforms. Safeguarding the independence of good journalism as it becomes a subset of social media is a critical task for both publishers and platforms.

At the end of 2016, battered by the negative publicity for Facebook around “fake news,” Mark Zuckerberg retreated from his rigid position that his creation was “just a technology company,” to acknowledge that it was a “new kind of platform.”

Technology companies including Apple, Google, Snapchat, Twitter, and, above all, Facebook have taken on most of the functions of news organizations, becoming key players in the news ecosystem, whether they wanted that role or not. The distribution and presentation of information, the monetization of publishing, and the relationship with the audience are all dominated by a handful of platforms. These businesses might care about the health of journalism, but it is not their core purpose.

News publishers are struggling to understand how to work with these powerful new forces in the industry. The rapid adoption of smartphones has transformed media consumption, turning technology companies with their apps and operating systems into the new gatekeepers of information. According to 2016 Pew data, 92 percent of young Americans from 18 to 29 own a smartphone, and 77 percent of the population as a whole—higher than the number with broadband connections at home. Over 62 percent of the US population gets news from some form of social media, with Facebook the dominant source. The length of time that people spend looking at their screens and the volume of personal data collected by these companies have created a completely new operating environment in which journalism must now function.

Social media and search companies are not purely neutral platforms, but in fact edit, or “curate,” the information they present. Platforms for their part have started to acknowledge the role they play in news provision. But the exercise of editorial judgment has complicated their commercial mission: to get as many people as they can using their platforms as often as possible. The contradictions inherent in this developing role has led to rapid shifts and reversals in strategy. In August 2016, for example, Facebook fired its 30 editors or “curators,” as it called them, to counter reports that the company was unfairly editing Trending Topics to suppress stories from conservative news outlets. Shortly after this, coverage of “fake news” suggested that the company ought to have had more rather than less direct editorial intervention on its platform.

Even after the “fake news” scandal of the last election cycle, Mark Zuckerberg insisted Facebook “must be extremely cautious about becoming arbiters of truth ourselves.” Instead, the company formed partnerships with several fact-checking and news organizations to flag dubious stories. Its partners were believed to be unpaid.

Journalism and news organizations stand at a critical point in their history as an independent force in democratic society. The opportunity to reach a global audience through the swipe of a finger is here, and it offers tremendous journalistic possibilities that are still not fully understood. But hyper-connectedness through the social web and mobile telephony has created a vast marketplace of information of which journalism is only a small part. The essential nature of journalism has not changed; it is still about reporting stories and adding context to help explain the world. But now it is threaded through a system built for scale, speed, and revenue.

The platforms’ business models incentivize “virality”—material people want to share—which has no correlation with journalistic quality. The architecture that enables news organizations to reach their audiences on social platforms also militates against their sustainability.

Universal access to accurate information is at the heart of a well-functioning democracy, and that access is now shaped by the enormously powerful and largely unaccountable technology companies of Silicon Valley. While the market for information is still evolving rapidly, we have an opportunity to create a more robust and transparent model for journalism.

Journalism’s Third Wave

The impact of social media on journalism has been as great an upheaval as any other in the history of the industry.

During the first phase of web development in newsrooms—which stretched roughly from the advent of the commercial internet in 1994 to the widespread availability of broadband in 2004—the principal concern among news organizations was how to transfer print products to the internet. In many traditional organizations there was deep uncertainty around this shift, but beyond that there was a hope that a new digital ecosystem could be built on the traditional values and methods of journalism, where a financial model supports, and even innovates around, the core accountability and civic functions of the free press.

In the next decade, the wider availability of broadband and Web 2.0 technologies made it possible to publish multimedia material anywhere. Interactive journalism, comments on articles, podcasting, and crowdsourcing all offered exciting opportunities for journalism. Small sites like Homicide Watch DC won awards for demonstrating the power of using databases to build and tell stories with a team of just two. Journalists collaborated to build completely new tools like the public document hosting site Document Cloud. In 2007 the first iPhone was launched and the opportunities for reaching new audiences grew even further.

The emergence of the internet, and the principles of the open web that initially underpinned it, wrenched control from the few, transferring it to the many. It was, at its core and in its design, a democratizing technology.

An explosion of new websites and services sprang up in the US over this period. From nationally focused players such as Huffington Post, ProPublica, Business Insider, Quartz, BuzzFeed, and dozens of others to local innovators like The Texas Tribune, Patch, Deseret News, and others. Larger legacy organizations like CNN, the BBC, The New York Times, and The Washington Post were in a state of constant revolution, with varying degrees of success.

While this period saw tremendous experimentation, the financials were grim. For much of the twentieth century, journalism had been supported through three main revenue sources, all of which were undercut by the internet. Classifieds and display advertising were upended by Craigslist and Google, respectively, and subscriptions proved difficult to generate for digital products. These three trends exacerbated each other: necessary digital transition and experimentation was stalled by the reliance on slowly declining, but still significant, print circulation revenue.

This didn’t simply reduce advertisers costs and publishers’ revenues. It also broke the vertical integration of the industry, which guaranteed access to audiences through privileged and high-cost distribution systems. In the open web, the attributes that once bound the industry together—the similarity of methods among a relatively small and coherent group of businesses, and an inability for anyone outside that group to produce a competitive product—were no longer present.

While this twin shift—in both the production and funding of news—was highly disruptive to established news organizations, it was also championed by many as a positive evolution in the practice of journalism. The civic design of the internet and the civic purpose of journalism were ultimately aligned.

Now we are experiencing a third wave of technological change. The move from desktop computers to the small screen of the smartphone and the development of a privatized mobile web enclosed and monetized the promise of the open web. The principles of the open web, which held promise for citizens and journalists alike, have given way to an ecosystem dominated by a small number of platform companies who hold tremendous influence over what we see and know. The internet we see today, one largely controlled by two to three companies, is a far cry from the open web of Tim Berners-Lee.

In the past two years alone, the integration between the news business and social platforms such as Facebook, Twitter, Snapchat, and Google has accelerated. Globally there are well over 40 different social media sites and messaging apps through which news publishers can reach segments of their audience. Facebook operates at a scale hitherto unseen. No publisher in the history of journalism has enjoyed the same kind of influence over the news consumption of the world.

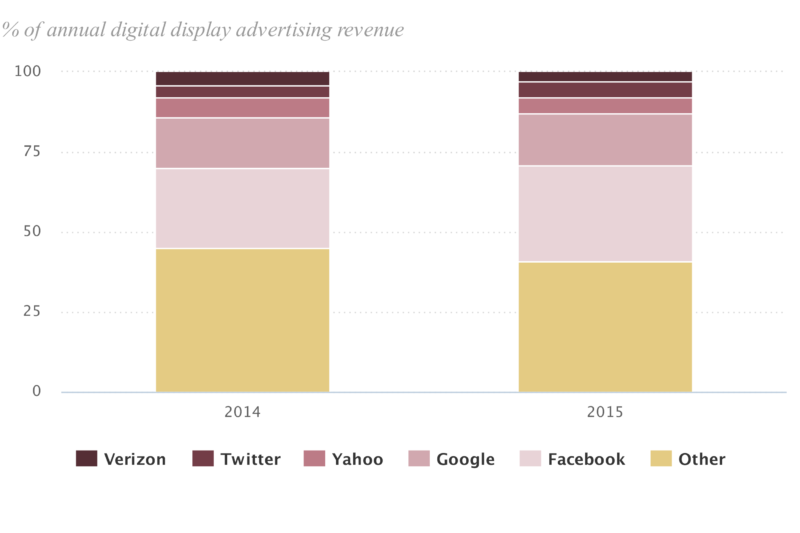

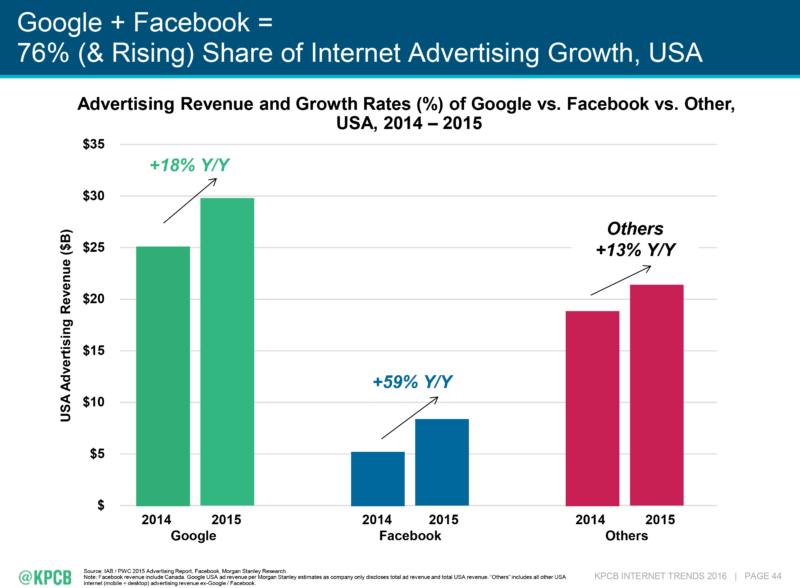

The rebundling of publishing power is arguably responsible for a mass defunding of journalistic institutions. Verizon, Twitter, Yahoo, Google, and Facebook take more than 65 percent of all digital advertising revenue, according to Pew in 2016. Digital Content Next reported that 90 percent of growth in digital ad revenue over 2015 went to Facebook and Google. This change does not encourage confidence in the idea that the closed environment of platforms is beneficial to the long term health of journalism, without dedication on the part of technology companies to make it so.

The influence of these companies over the exchange of information is often dictated by socio-technical systems that are hidden from view, and driven by incentives that are in private, rather than public, interest.

We seek to shed light on the dynamics of the convergence between publishers and platforms, using new findings from more than 70 interviews conducted over the past 12 months, and from content analysis conducted over four one-week periods. (See Appendix I for more on our methodology.) We also hosted two private roundtables, each with more than a dozen participants: one with academics and researchers focused on some aspect of this relationship, and one with social media managers from news organizations with varying business models. We focused our research and this report (and the timeline in the appendix) on the platforms being used most by, and having the greatest impact on, news organizations.

Fake news, filter bubbles, the “post-truth society,” and the decline of trust in the media are dominating the public debate. All of those issues are proxies for the fundamental question of how our world of news and information has been upended by technological change. This report is our contribution to a better understanding of that change.

Major platform launches, announcements, and acquisitions

(See the appendix for fuller list.) The frequency and type of publishing related developments among platforms has accelerated over time as platforms compete to meet the needs of as many publishers as possible. Platforms are more explicit about their relationship to news, formalizing their relationships with publishers, and, in some cases, stepping into editorial territory.

February 2, 2004: Facebook launches as a Harvard-only social network.

July 15, 2006: Twitter launches as Twttr. “Tweets” can only be 140 characters.

September 5, 2006: Facebook News Feed launches, displaying activity from a user’s network.

May 1, 2009: WhatsApp, a mobile messaging app, launches.

October 6, 2010: Instagram launches as a photo-based social network.

September 26, 2011: Snapchat launches as a mobile app for disappearing messages.

October 12, 2011: Apple Newsstand, an app to read a variety of publications, released.

April 9, 2012: Instagram acquired by Facebook for $1 billion.

October 3, 2013: Snapchat Stories, a compilation of “snaps” a user’s friends see, launches.

November 20, 2013: Google Play Newsstand, an app to read a variety of publications, released.

January 30, 2014: Facebook Paper and Facebook Trending launched. Paper was an effort at personalized news. Trending is a list of the platform’s top topics.

February 19, 2014: WhatsApp acquired by Facebook for $19 billion.

April 24, 2014: Facebook Newswire launches. Publishers could embed newsworthy content from Facebook into own material, and use platform for newsgathering and storytelling.

June 17, 2014: Snapchat Our Story—a public Story aggregating many users’ activity around an event—launches.

January 27, 2015: Snapchat Discover launches. Selected publishers create a daily Discover channel, like a mini interactive magazine.

March 9, 2015: Twitter acquires Periscope, a livestreaming video app.

March 31, 2015: Twitter Curator launches. Publishers can search and display tweets based on hashtags, keywords, location, etc.

May 12, 2015: Facebook Instant Articles launches. The faster loading articles within Facebook on mobile provide a 70/30 revenue share with publishers if Facebook sells the ads against the article.

June 8, 2015: Apple News announced, replacing the Newsstand app; 70/30 revenue share if Apple sells ads against content.

June 22, 2015: Google News Lab launches to support technological collaborations with journalists.

August 5, 2015: Facebook Live launches Live video streaming.

September 23, 2015: Facebook 360 video launches. Users can move their phones for a spherical view within a video.

October 6, 2015: Twitter Moments launches, providing curated tweets around top stories.

October 7, 2015: Google AMP announced. Accelerated Mobile Pages will allow publishers’ stories to load more quickly from mobile search results.

November 11, 2015: Facebook Notify, a real-time notification news app, launches.

November 13, 2015: Snapchat Official Stories launches with stories from verified brands or influencers.

June 9, 2016: Facebook 360 photo launches. Users can move their phones for a spherical view within a photo.

August 2, 2016: Instagram Stories launches, a Snapchat Stories clone.

November 21, 2016: Instagram launches Live Stories for live video streaming.

December 12, 2016: Facebook Live 360 video launches, giving users a spherical view of live video.

December 20, 2016: Facebook Live audio launches, allowing for formats like news radio.

January 11, 2017: Facebook Journalism Project announced to work with publishers on product rollouts, storytelling formats, promotion of local news, subscription models, training journalists, and collaborating with the News Literacy Project and fact-checking organizations.

February 14, 2017: Facebook TV announced: an app for Apple TV and Amazon Fire that will allow people to watch Facebook videos on their TVs.

Platforms Become Publishers

After more than a year of research into the relationship between platforms and publishers, it’s clear that no newsroom is unaffected by the gravitational force of big technology companies. Decisions made by Facebook, Google, and others now dictate strategy for all news organizations, but especially those with advertising-based models. Platforms are already influencing which news organizations do better or worse in the new, distributed environment.

Starting in Spring 2016, through a mix of content analysis and over seventy interviews, the Tow Center started tracking exactly how publishers are using social media to distribute their journalism, looking at a sample of both publishers and platforms. The publishers covered include legacy businesses, new digital publishers, and video-based news organizations, with a mix of business models, from subscription to advertising-based and non-profit.

Publishers remain confused or undecided about how best to leverage relationships with technology companies. A growing number of news organizations see investing in social platforms as the only prospect for a sustainable future, whether for traffic or for reach. But algorithmic opacity makes it difficult for publishers to plan with certainty. What works now is not guaranteed to work in the future.

Relinquishing control of distribution has led to a greater transfer of power from publishers to platforms than anticipated. The single most controversial, influential, and secretive algorithm in the world is the one that drives the Facebook News Feed. While publishers can freely post to Facebook, it is the algorithm that determines what reaches readers; Cynthia Collins, social media editor of The New York Times, said, ”We surrender so much control in terms of what gets read.”

As platform competition increases—Facebook and Twitter are, for example, both pursuing exclusive video deals with publishers—and their publishing tools are refined, news organizations have become more discerning about choosing partnerships. While publishers are publicly skeptical of the value of integrating their journalism with platforms, our data show they are nevertheless still publishing high volumes of articles and videos within proprietary systems or “walled gardens.” Publishers might want to pull away from the system, but few are actually doing it.

Platforms, particularly Facebook, have dramatically altered their attitude toward news publishing in the past six months. Facebook added a Head of News Partnerships in the shape of former journalist Campbell Brown, hosting a series of workshops and hackathons focused on how to make Facebook better for journalists, and engaging in a vigorous program aimed at raising the issue of media literacy in the public sphere. Since the election (when the algorithm was credited, perhaps wrongly, with delivering vast swathes of misinformation and “fake news,” in a way that affected the political process), there has been some investment in third-party services such as fact-checking. But there is no sign yet of a more significant transfer of wealth from technology companies to news organizations. Our research describes the scale of the changes in four areas: distribution and marketing, hosting and production, relationships with audiences, and monetization.

A world of choice—but at a cost

This is the biggest problem of the world: Facebook has bought two-thirds of the new media companies out there without spending a dime because they own a majority of their mobile. That’s great for Facebook, but bad for their platform. That’s why we’re trying to get on all platforms because if we can monetize on all platforms then we can get away from the patrimony of Facebook.

You’re giving another company your manifest destiny. Unless you are on those platforms, you’re dead, but if you are on those platforms then you’re not making money, so therein lies the rub and that’s going to be biggest challenge in media going forward.”

Audiences have moved onto the mobile and social web, and news organizations have had no choice but to follow. Understanding how to reach audiences, how to keep them, and how to thread each piece of journalism through a complex maze of different sites and applications, has fundamentally changed the way newsrooms operate.

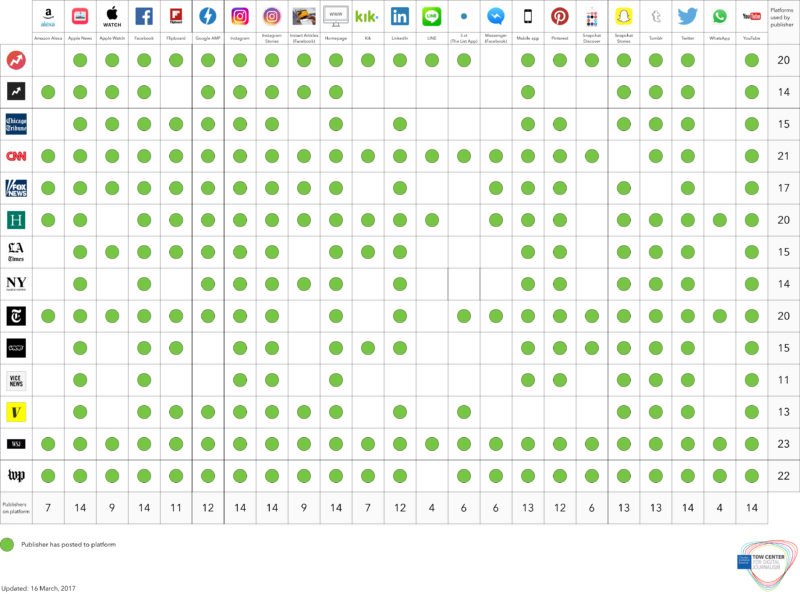

This chart demonstrates just how many third-party options publishers are dealing with. While it might not be as competitive and diverse as it appears from the platform side, Facebook, Instagram, and WhatsApp are all Facebook-owned companies. The options represent a dazzling array of new opportunities to reach audiences. Or from another perspective, they show “everything wrong with journalism in one chart,” as Jessica Lessin, founder of The Information technology newsletter, tweeted:

@morganb everything wrong with journalism in one chart

— Jessica Lessin (@Jessicalessin) February 24, 2017

How the 14 diverse news organizations in our sample use 21 different technology platforms.

Facebook and Google are by far and away the most important external referral sites for news traffic. According to publishing industry monitors Parse.ly, by the end of 2016 Facebook was responsible for 45 percent of referral traffic to publisher sites, and Google 31 percent.

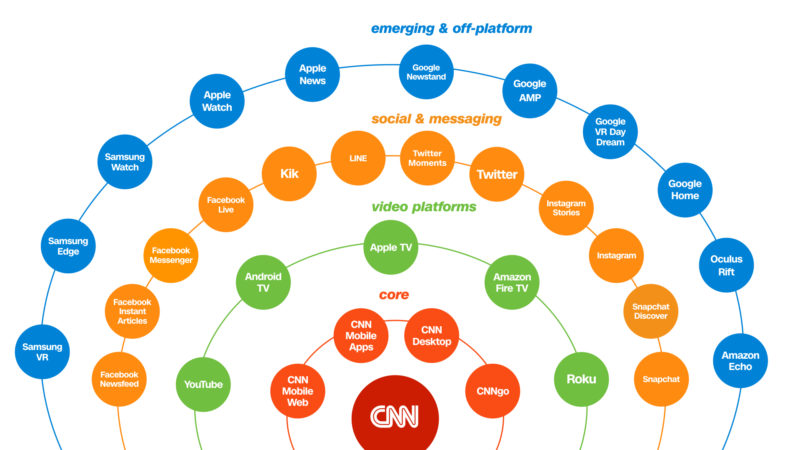

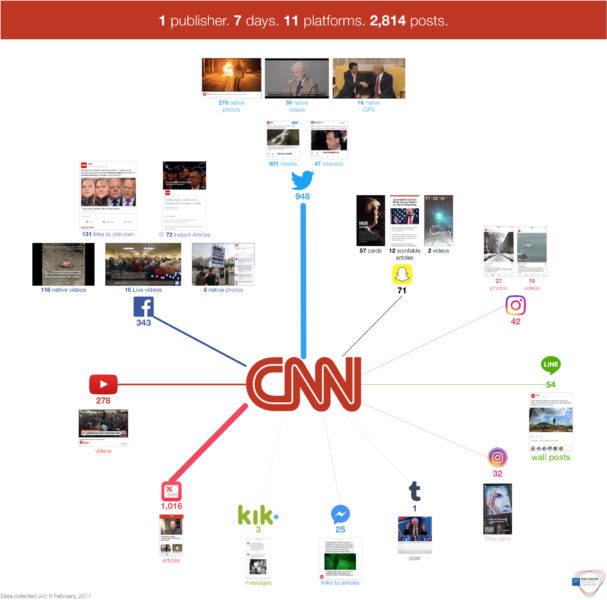

A sense of how this looks for publishers, and affects their editorial decisions, is provided by the chart below, which was shared by Meredith Artley, the editor-in-chief for digital at CNN.

Her point was to show the complexity of the choices available to publishers. At the center of the chart sits CNN, and on the inner ring the numerous different brands and proprietary platforms the news network publishes on digitally—mobile web, mobile apps, desktop and CNNgo. Beyond that is a layer of new video platforms—YouTube, Android TV, Apple TV, Amazon FireTV, and Roku. Then the social and messaging layer—Facebook Live, Facebook Instant Articles, Facebook Messenger, Facebook News Feed, Instagram, Twitter, LINE, Kik, and Snapchat. And then an outer ring of “emerging and off-platform” services, which stretch the idea of a social platform: virtual reality, Apple and Samsung watches, Amazon Echo, and Google AMP.

Beneath each one of those colored circles, there is a set of different decisions about what to publish, when, and how. Sometimes it is just part of one person’s job, sometimes it is a whole team,” said Artley, who has a global team of over 50 dedicated to fashioning stories for distributed platforms. “Our aim is to be number one in video news for mobile—everything is oriented around that goal.”

Organizational editorial product chart. Courtesy of CNN Digital.

Balancing the opportunities of social distribution against investing in a proprietary platform is a key strategic question for news organizations. “You have to do both,” says Mark Thompson, chief executive of The New York Times, which has staked its sustainability on reaching large numbers of potential subscribers. To develop loyal readers, the Times plants what they call growth editors across desks and sprays social platforms with Times links. Even BuzzFeed, which started from the premise that it would live on social and would not spend much time worrying about the presentation of its own website, has adjusted its course, and relaunched its homepage in 2016. Editor in Chief Ben Smith, talking at a panel on fake news in 2017 said that, contrary to expectations, “homepage traffic kept going up, as people liked what they saw, liked our brand, and went to the homepage.”

However, a high proportion of many news organizations’ content is designed to be consumed natively, on platforms including Apple News, Facebook Instant Articles, Instagram, and Snapchat, rather than driving audiences back to publishers’ websites. Native publishing products, including Google AMP pages, Facebook Instant Articles, Twitter Moments, Apple News, Snapchat Discover, Instagram Stories, mean that a reader might look at a story from The Economist on Google without ever touching The Economist’s own app or site.

This chart shows the total number of pieces posted to native pages on social apps, compared to the number on social media with a link back to their home site.

[visualizer id=”66346″]

Total number of native (residing on platform) and networked (driving audiences back to websites) posts made by 14 publishers in our sample, the week commencing February 6, 2017. See Appendix I for full list of publishers.

While publishers all need to have a presence across a broad range of platforms, how they distribute their content—and, in particular, the amount they “give away” to platforms in the form of native content—differs considerably.

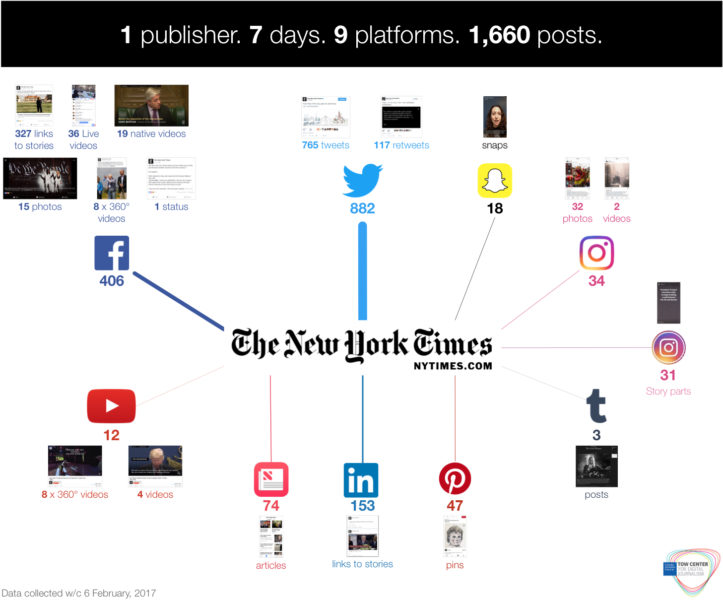

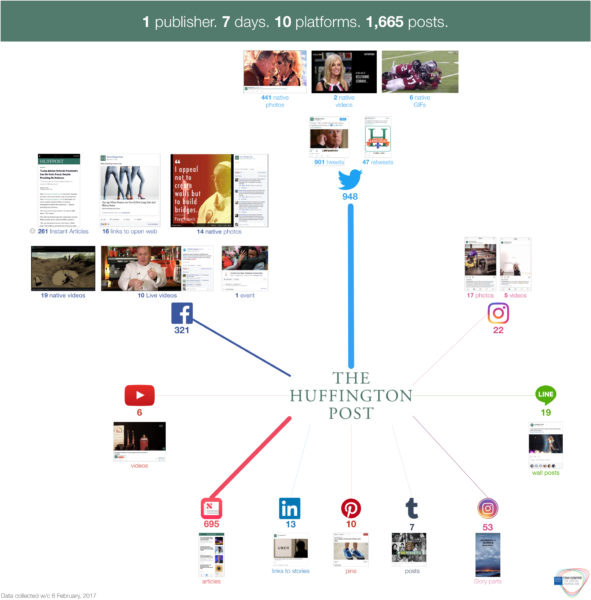

Compare, for example, The New York Times, The Huffington Post, and CNN during a week in February. All three publishers were active on 10 different platforms over the course of the week. During the period, The Huffington Post and the Times made an almost identical number of posts across platforms (1,655 and 1,673, respectively).

Posts made to platforms by The New York Times during the week commencing Monday, February 6, 2017.

Posts made to platforms by The Huffington Post the week commencing Monday, February 6, 2017.

However, there were sharp differences in their use of native and networked content. While native content means pieces entirely hosted on third-party platforms such as Snapchat Discover or Apple News, networked content means links posted to media that send the reader to originator’s own site. Two-thirds of posts from The Huffington Post (66 percent) are in native formats, including 695 articles on Apple News and 305 pieces of native Facebook content (Instant Articles, live video etc). These native Facebook posts also represent 98 percent of Huffington Post’s total Facebook posts. By contrast, just 16 percent of the Times’ posts across platforms were native; the remaining 84 percent were designed to drive audiences back to nytimes.com, where they can consume a small amount of the Times’ journalism for free before being required to pay for a subscription. Having since abandoned Instant Articles, just 79 of the Times’ 406 Facebook posts (19 percent) at the time were native to the platform. And only 74 articles were posted to Apple News, the lowest number we have recorded for the Times in four rounds of quarterly data collection.

A third approach is visible in CNN, with its generous smattering of posts across platforms. While the proportion of native (59 percent) content is broadly comparable to that of The Huffington Post, what stands out about CNN’s strategy is the sheer volume of posts made across platforms of all kinds. The total of 2,811 (around 40 percent more than both Huffington Post and the Times) includes 1,016 articles on Apple News, 948 tweets, and 278 YouTube videos. CNN’s concerted effort to reach younger audiences is also evident in its Snapchat Discover channel, on which we saw a shift away from scrollable articles repurposed from cnn.com to more bitesize news cards, and its ongoing commitment to chat app LINE.

Posts made to platforms by CNN during the week commencing Monday, February 6, 2017.

Taken to the extreme, the strategy of emphasizing distribution produces NowThis News, a video news service which tells readers (on its landing page) that there is no homepage: “HOMEPAGE. EVEN THE WORD SOUNDS OLD. WE BRING THE NEWS TO YOUR SOCIAL FEED.” The embrace of platforms is shaped by the business model of the publisher, in the case of NowThis, ads and scale.

Platform strategy varies with news organizations’ business models. Jim Brady, founder and CEO of Billy Penn, a Philadelphia mobile news platform, said that when it came to Instant Articles, “I can afford to be a little bit more agnostic about it than someone whose revenue is tied to where the page view lies.” Gabe Dance, former managing editor of the not-for-profit news organization the Marshall Project said their resources were focused on “impact” because that’s what funders care about. And, after an unsuccessful experiment with NPR to host audio natively on the platform, Wright Bryan, senior editor for engagement, walked away wondering, “Does audio really fit a format like Facebook?”

While overall it was clear how business models shaped platform strategy, there are outliers, like Vice, which like NowThis News, depends on ads and scale:

I think because there’s a continuous debate as to the very question: ‘What do you need to control, and what things do you not?’ Going all in, solely on the platform to support your entire ecosystem in every way, is a big gamble.

—Sterling Proffer SVP, Head of Business Strategy & Development of Vice

We also saw dramatically different patterns of use over time. The chart below shows what some of the major players were doing on Facebook’s Instant Articles as of February 2017:

[visualizer id=”66359″]

Proportion of Facebook links posted as Instant Articles, during the week commencing Monday, February 6, 2017.

- The Washington Post (96%),The Huffington Post (94%), Vox (92%), Fox News (91%), BuzzFeed News (90%), and BuzzFeed (85%) have fully embraced Instant. (The Washington Post is no surprise; it decided to go all in on Instant Articles as early as September 2015.)

- The Wall Street Journal, which relies on subscriptions, posts a tiny proportion of their links as Instant Articles (3%).

- The New York Times, Chicago Tribune, Los Angeles Times, and Vice News are not using Instant articles. The New York Daily News (20%) and CNN (35%) are striking a middle ground.

But for smaller and local publishers, choice—about which platforms to use, and how far to go in on them—feels like a luxury. “We are outsourcing our core competency to third parties. We simply don’t have a choice,” said David Skok, a digital media executive who has worked for among others, the Boston Globe and Toronto Star. “I feel as if we are collateral damage in the war between these platforms. They’ll give some publishers a chance to play, but not others. They’ll give favorable rates and treatments to some and not to others. They are already picking winners.”

Take Snapchat for instance: Snapchat Discover is only available to a limited number of publishers. The platform decides who to offer contracts to, and publishers must commit to performance terms. Discover, the most resource intensive of the social platforms, is serviced by newsroom teams of up to a dozen or so people that produce and redesign stories to fit the platform. What was once a healthy size of team for a small website is now managing a mix of original and repurposed journalism for one social app. Many publications do not have the right brand to be attractive to Snapchat, or the resources to service its requirements. Overall, resource was a concern in smaller newsrooms when it came to platform distribution. “Their pitch to us is [that] it’s totally free to [use these tools],” said one local publisher about Instant Articles. But it’s not free in that it takes a staff member’s time to to it.

Still, when a platform introduces a new format, publishers tend to adopt it quickly. Instagram Stories was only one week old when we collected data in August 2016, but many publishers were already showing a willingness to use it. During the week of our analysis, we recorded 151 stories across five accounts. (CNN in particular used it extensively in coverage of the Rio Olympics.) During election week, that figure jumped to 253 stories from eight accounts, dropping only slightly during our February collection to 228.

The efficiency with which platforms reach far larger and more targeted audiences is the single largest benefit to news organizations and individual journalists. The scale is addictive. With 1.86 billion active monthly users on Facebook, 313 million on Twitter, and 1.2 billion on WhatsApp, and 160 million daily active users on Snapchat, the connective power of platforms is only growing. Innovation now surfaces on services such as Instagram, where there are seamless opportunities for creating new offshoots or verticals for publications.

Billy Penn, a local, mobile-first site serving Philadelphia, is the type of business that would not exist without the new distribution structures. While its revenue comes primarily from events, and therefore it is not as dependent on platforms like Facebook for ad revenue, it still relies on Facebook to reach audiences about those events. “To be a site going after an 18 to 34 audience and say we’re going to sit out these external platforms—it’s just like opening a restaurant in St. Petersburg [Florida] and not being open for the Early Bird Special,” Jim Brady of Billy Penn, a veteran of digital publishing, said. “We’re fine to subsume the brand to Facebook if it helps us get in front of more people.”

Brady’s sanguine approach to the trade off between brand and reach touches a key source of anxiety for many. Pew found that only 56 percent of online news consumers who had clicked on a link could recall the news source (2016). And the American Press Institute’s Media Insight Project (2017) found that on Facebook only 2 of 10 people could recall the source, while far more trust was placed in the sharer. “If we’re out here for branding and nobody even recognizes it, if our brand is related to the Snapchat brand then . . . maybe it’s not worth it,” says one magazine publisher.

Another local publisher interviewed for our report notes that, in the embrace of a larger news environment, their local readers feel distant:

I think when our content is removed from the context of our own sites and placed in a different display, such as Facebook, it’s natural to assume that some of the branding will be lost to the new host. We have to work harder now to build that brand recognition and loyalty.

Now, scale is everything, from number of likes and shares to ultimate reach; social platforms have leveled the playing field for content, prioritizing shareability over everything else. Newsrooms were chasing traffic and shares before the advent of Facebook, and have themselves played a large role in defining the metrics that have shaped the current ecosystem. Many of the tricks of making fake news perform virally are taken straight from the historical playbook of tabloid or yellow journalism. The popular items often have headlines that promise more than the piece delivers, sensational or aggressive opinions that grab attention and stir controversy, or endlessly repeat already popular stories.

We are telling stories that other outlets aren’t telling, which is almost to our detriment in the world of viral news. When it comes to the way Facebook and Twitter currently surface trending content and breaking news, it’s not about the story that no one has. It’s about the story that everyone has.

—Delaney Simmons, Director of Digital Content and Social for WNYC

Back in 2013, AllThingsD reporter Mike Isaac wrote a piece entitled, “Facebook Wants to be a Newspaper, Facebook Users Have Their Own Ideas,” which laid out the vision Mark Zuckerberg and Facebook’s Chief Product Officer Chris Cox had for the platform and News Feed that it would be a paragon of “useful”-ness. The reality, however, was that users wanted to see cat videos, and memes and jokes—they weren’t looking for Facebook to be “useful.”

As Isaac noted at the time: “The gap between these two Facebooks—the one its managers want to see, and the one its users like . . . —is starting to become visible. Earlier this year, Facebook users rejected a redesign that Zuckerberg announced with much fanfare. Now Facebook is adjusting its algorithms to emphasize content that it thinks readers should see, which will push down some of the stuff that’s currently popular. Which version of Facebook will win out?”

Building your house on someone else’s land

When you launch on a new platform, you connect with new audiences that may be different in some ways from your typical readership. For us, it’s important to ask ourselves how do we stay authentic and maintain our voice in order to publish in a way that makes sense on that platform.

—Carla Zanoni, Executive Emerging Media Editor, Audience Development, of The Wall Street Journal

The integration of journalism within the fabric of the social web started a long time before any of the smart new publishing formats and tools came into being. In 2009 Facebook launched a plug-in option to host comments from websites on its platform, alleviating news organizations’ need to tangle with the expensive and difficult business of moderating comments. Publishers who adopted the idea of Facebook hosting their comments were relieved and delighted that the part of their universe they found the least rewarding—reader interactions—were given to an expert hosting community. But it also meant that the shape of social conversations was controlled by Facebook rules—real name policies, and of course a Facebook profile.

Facebook allowed publishers to launch “social reader” apps in 2011, and it was adopted by publications including The Washington Post and The Guardian. The social reader was a forerunner to Instant Articles in that it hosted the journalism within a Facebook app, and drove enormous traffic to the pieces featured. Two problems dogged the experiment however: Traffic patterns were unpredictable—an early manifestation of the News Feed algorithm problem—and it spooked users by showing people in their social graph what they had been reading.

Since then, platforms have been developing exponentially more tools to move publisher content onto their sites. It is not a surprise that social platforms are better at hosting social content and conversations; after all, it is their core business. While news companies had tried to retrofit community and engagement into their monolithic websites for a decade, social media started from the proposition that the environment created was for everybody, to allow everybody to publish.

The tools for publishers to help them produce material on specific platforms—such as Facebook Live video, Instagram Stories, Snapchat Discover, and Twitter Moments—serve the dual purpose of allowing journalists and news organizations to produce stories directly onto a platform, and allowing platforms to incentivize the type and format of the journalism they host. Video is a more expensive advertising medium, and Facebook has prioritized it. When Facebook introduced its Live video product for publishers it took the unusual step of paying publishers up to $5 million each to use it.

The incentivizing of publishers to produce certain types of content is driven by the demands of the advertising market. Video and images are more powerful for advertisers than words. Mark Zuckerberg in 2015 said that much of the content on Facebook, “fast forward five years, it’s going to be video.” This is a reflection of economic realities for an advertising platform.

The problem for publishers is again the cost of production. Video is both more difficult and more expensive to produce than text. But Facebook has been clear that mid-roll ads would play at 90 seconds, pushing publishers toward longer videos, and says longer videos will be prioritized by the algorithm. And, unlike with Instant Articles, Facebook always gets a cut of video ad revenue.

All publishers in our interviews saw the allocation of resources and the creation of work on third-party platforms as a daily reality.

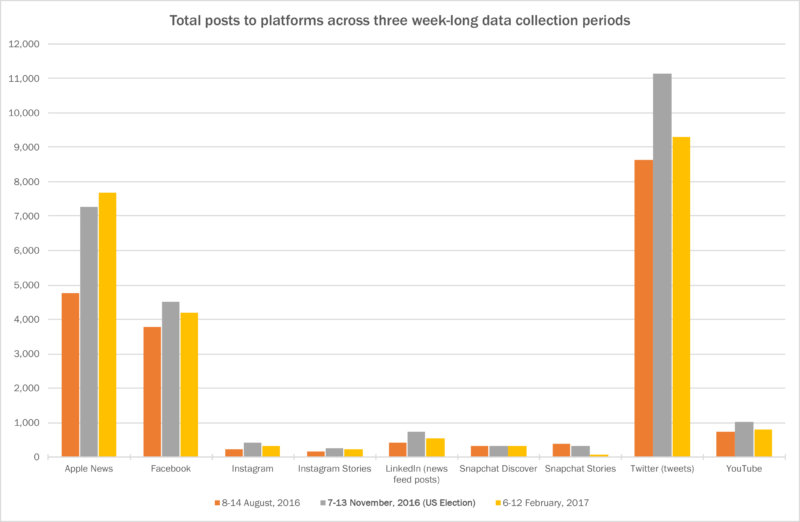

Total number of posts made to major platforms during our three most recent phases of data collection, 2016 and 2017.

While at one time internal technology teams at news organizations were developing formats and products within their own platforms, they are now likely to also be focused on how to develop products that integrate with a third-party platform.

At platform companies there is a great deal of clarity that they believe they can create far better publishing tools and environments than publishers, just through scale and expertise. Virtual reality, artificial intelligence applications like Amazon’s Alexa, and Google’s Home, augmented reality, are all difficult to develop within individual newsrooms.

But with these new tools come new costs. News organization structures, workflows, and resource allocation are increasingly dictated by platforms, according to our interviews. Where publishers once had social media managers, increasingly there are staff dedicated to managing specific platforms, creating content for those specific platforms, and managing the consequent relationships, and increasingly these teams are central to the newsroom. Cynthia Collins of The New York Times jokingly referred to regular check-ins with Facebook during the early days of Instant Articles as “the state of our union together meetings.”

And while platforms may not have a say in the editorial choices of newsrooms, in hosting their work, they undoubtedly shape those choices. Some of the accommodations publishers make are minor, and more in service of user behavior on a platform than the platform itself. For example, people were muting videos on Facebook, so publishers moved toward a text-on-screen format. Others, like Snapchat, require a sort of mini-newsroom. But in some cases, our research showed a more direct influence. In one case, Snapchat commenting on a publication’s logo; and in another, it asserted the genre of content a publisher should focus on.

Publishers are making micro-adjustments on every story to achieve a better fit or better performance on each social outlet. This inevitably changes the presentation and tone of the journalism itself. Publishers might say that metrics are only one indicator of performance, and that the core values of a news organization are not shaped by them. However, the central role of audience strategists and social platform editors in deciding which stories are commissioned is increasing. One publisher said that if their audience team doesn’t think a story will perform, it may not be assigned.

In other cases, the way platforms build new products is becoming more editorial. Twitter has a team of curators who package together fragments of stories into Moments. This represents a form of editing for social platforms. Snapchat created a Story for the San Bernardino shooting. Facebook employed editors to curate its Trending section. YouTube and Instagram work with individuals to help them craft content for the platforms. Growing partnership teams in each of the platform companies are in constant contact with the editorial and social teams within news organizations.

“The relationship between newsrooms and outside businesses is brand new. Especially within the newsroom, it’s a new experience for us to discuss with an outside party what content mix performs well on which platform and work within the constraints of having someone direct us in some way,” said Carla Zanoni, Executive Emerging Media Editor, Audience Development, of The Wall Street Journal.

Whose audience is it anyway?

What do we claim as our audience? And how do we monetize that? When we go to an advertiser and they say, ‘We’d really like to know what’s on your dot com,’ . . . it’s like, do you have any understanding of how people consume content?

—A magazine publisher

With hosting, distribution, and monetization all being handed over to platforms, the critical advantage they gain is the capture of data about the audience. The billions of active users all leave data trails within the proprietary systems of the companies. Every time a user logs on to a site using Facebook’s very efficient universal login, more data is gathered about the user. Facebook can track its users both on and off its site, and this matching of large data sets enables much finer grain targeting by the bigger companies, and therefore potentially higher revenue from advertisers. The data helps platforms configure products and algorithms that adapt instantaneously to user behavior.

The process for buying an advertisement on Facebook or promoting an editorial post is the same: as the advertiser you are asked to create a targeted demographic, depending on location, profile information, and even affiliations Facebook has collected from both the direct input and the wider behavior of users. Once the audience parameters are set, the post or advertisement will be targeted at the select individuals. As long as the material is compliant with Facebook’s terms of use, almost anything can be promoted through payment, and often is.

Understanding that profile information—the accrual of data around the behavior of those who use the platform—is essentially the way that Facebook and other social platforms interpret their relationship with the user, and is critical to understanding the business engine of social media. When Facebook says it has listened to its users, it has not only literally listened to its users through surveys. It has also interpreted behavior from data.

When the Tow Center hosted a conference on the subject of the relationship between Silicon Valley and Journalism in November 2015, Facebook executive Michael Reckhow, who at the time was in charge of the launch of Instant Articles, referred to Facebook users as readers, saying “we think of our readers as the customers that we want to serve with great news.” Mark Thompson, the chief executive of The New York Times, referred to Times readers on Facebook as the Times’ readers. How that relationship with news brands develops—whether we discuss Facebook users reading the Times or Times readers on Facebook—is of overwhelming importance.

The biggest change across all outlets we monitored and interviewed over the past year has been the acknowledgement that their brand and destination are important. The New York Times, The Washington Post, and even nonprofit ProPublica saw surges in subscriptions or donations after the US election. This idea of a direct relationship with readers is critical for all subscription or membership businesses, and as the faltering advertising drives publishers into direct payment models the ownership of that relationship is essential. Data in many cases is a proxy for “relationships.”

Success, says Carla Zanoni of The Wall Street Journal, “hinges on the nature of the platform and your ability as a publisher to engage with that audience and build a long-standing relationship that extends beyond the platform.” But, the development of a new audience on a platform, and strategizing how to market to and monetize that audience, raises the question of “who owns the relationship with the user,” says Cynthia Collins of The New York Times, and “who controls that relationship and that data?”

Further, access to data is essential for publishers to measure the success of their distribution strategies and to evaluate their relationships with platforms. Platforms provide a promise of potential performance, not a guarantee, but publishers never have a crystal clear picture. Data access and clarity were a repeated concern from publishers throughout our interviews.

Haile Owusu, Chief Data Scientist at Mashable, said this creates limitations for even well resourced newsrooms to properly test the performance of Instant Articles. There is a “technical impediment to actually establishing just how much upside or downside there is,” he said. “Facebook gets to retain all the information. So, from a data perspective, our ability to assess the long-term value is explicitly cordoned off by Facebook.”

For years news publishers were drowning in customer data but had no ability or motivation to imagine what they might do with it. As data science has become an integral part of successful publishing, media companies are realizing they have lost something as valuable as money itself. Platforms, which are rooted in the use of data to build, launch, refine, and monetize products are by their construction always going to be at an immense advantage simply by dint of their vast scale. As one annoyed publishing executive put it: “They know more about our readers than we do—and can sell it back to advertisers in ways we can’t.” The platforms of course would contend the user is theirs in the first place.

Follow the money

The problem is not fundamentally Facebook or Google, it’s the internet . . . obsessing about how things would be fine if it wasn’t for Facebook and Google misses the point. The widespread hope that digital advertising revenue generated by vast numbers of unique users would be sufficient to pay for quality journalism was always illusory. Advertising revenue goes principally to those who control platforms. In print and TV, that has been news publishers, but in digital the platforms are technological: search, social networks and devices. Digital advertising is a useful supplementary revenue stream but, to successfully maintain high quality newsrooms, publishers need to attract paying customers.

—Mark Thompson, President and CEO of The New York Times Company

For those expecting the new swathe of integrated relationships and publishing on social platforms to increase their revenue, 2016 was a disappointing year. The news organizations we interviewed felt that return on investment goals for fashioning their journalism on different platforms was difficult to define, and, in the more recent interviews, that the monetary returns were low.

In order to understand this atmosphere, one needs to understand the rapidly changing nature of online advertising.

Digital advertising soars—for Facebook and Google

Over the past 10 years, advertising technology (adtech) has shifted power from publishers to advertisers. Adtech broadly refers to a set of digital tools that give advertisers both far larger audiences and more targeted audiences than before.

Google came to dominate the digital advertising market by building an end-to-end stack of software that provided all of the services that an advertiser (from a major brand to a local restaurant) would need to place an ad to a targeted group. This system was far more efficient than what publishers had historically offered (advertisers did not need to negotiate and purchase ads through human salespeople), far more targeted (there was no guess-work in the demographic that was seeing the ads), and infinitely more scalable (the market size was exponentially larger than any one publisher could offer). In so doing, Google replaced the core revenue driver for journalism. And, by capturing a large segment of a rapidly growing digital ad market, they emerged as the world’s most profitable media company.

Facebook was later to the advertising game than Google, but whereas Google dominated web advertising, Facebook focused on mobile. The problem for advertisers was that the cookies used to track user movement on the internet did not transition well between desktop and mobile devices. Because users were often logged into Facebook across their devices, their Facebook ID was able to more effectively track their behavior than cookies. In addition to this ability to track users more effectively, Facebook’s other advantage in advertising was the amount of data it had on the lives and behaviors of its 1.9 billion users. Not only data that users shared willingly, but also data collected by observing their behavior on the platform and eventually across the internet. With all of this data, ads could be targeted at specific user groups and inserted directly into their News Feeds.

Percent of annual digital display advertising revenue, 2014 and 2015. Source: Pew.

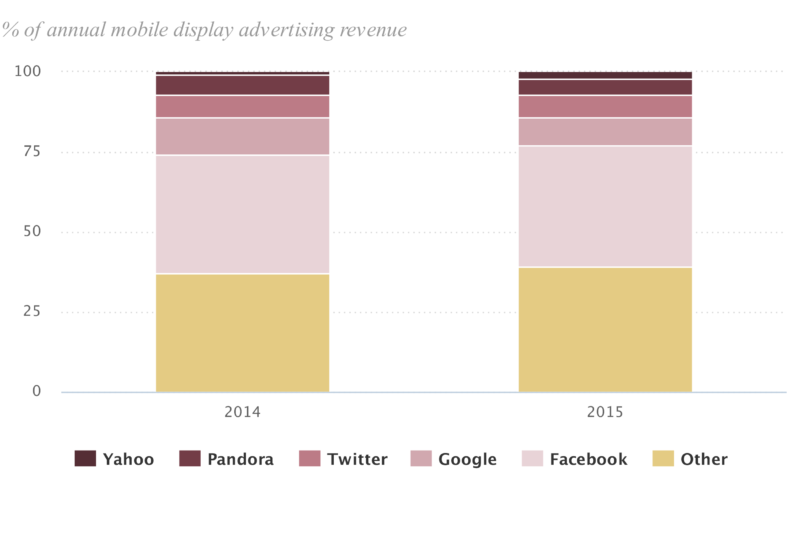

Percent of annual mobile display advertising revenue, 2014 and 2015. Source: Pew.

This upending of the advertising model has had serious financial repercussions for publishers, and is, in part, why many were willing to consider platform products like Instant Articles that allow access not only to new users, but new advertising opportunities.

Publishers could no longer claim the privilege of their demographic access nor the reach of their hyped-up circulation numbers. On the internet, an adtech company knows who is viewing the sports page and who is reading the in-depth reporting—and it can target ads directly to those individuals. In digital advertising it generally does not matter where an ad is displayed, only who sees it.

Because there is so much content on the internet and the adtech software is so efficient, the value per impression is very low (fractions of a cent and on a downward trajectory). In response, adtech networks have very low thresholds for participation, and Google and Facebook place few limits on who can participate in their ad products and the news products like Instant Articles against which those ads are placed. This leads to an environment in which scale dominates. This need for scale pushes even journalism publishers to create viral and click-bait content. While BuzzFeed produces remarkable works of journalism, it is the viral content that drives their revenue, and many legacy publishers have imitated aspects of BuzzFeed’s approach.

Digital advertising revenues soared in 2016. In the third quarter, digital ad revenue was 20 percent greater than the same quarter in 2015, according to International Advertising Bureau figures and the total for 2016 is expected to be over $70 billion. During the same period there was a dramatic drop in money spent on print advertising—over 8 percent for most publishers, the largest decline in print advertising since 2009. Large news publishers, even those like The New York Times and The Wall Street Journal, with healthy digital subscriber numbers, found themselves restructuring and losing staff. The problem for news publishers—outside the cable TV channels—is that digital advertising revenue is not growing fast enough.

Advertising revenue and growth rate of Google and Facebook versus the rest of the market. Source: KPCB Internet Trends.

Publishers determined to monetize audiences on their own sites, rather than on platforms, face an increasing threat: ad blockers. On mobile phones the kinds of data-heavy, intrusive ads that publishers traditionally hosted on their sites became not just more irritable but actually cost users time, and money—by chewing through their phones’ data plans. In 2015 Apple rocked the publishing world by listing ad-blocking software in its app store. It seemed as though even the minimal revenues from mobile advertising would be choked off.

As a result of adblocking and the limitless amount of available inventory, native advertising has become the only advertising format that works for most publishers in a digital environment. It has enabled organizations like Vox and BuzzFeed to disrupt the traditional agency business as their understanding of how to reach consumers through social is far more adept than most creative agencies. In addition, the footprint of their social traffic enables native advertising to travel down the same path as their editorial lists, quizzes, hot takes, and stories. After numerous requests from publishers, the ability to publish branded content as an Instant Article was added nearly one year after Instant launched, and just one week before it was opened to all publishers.

One magazine publisher said, of the importance of this advertising format, “They very much control the monetization piece and while it’s in their interest to allow us to do branded and native contents on their platform . . . they could change an entire industry overnight.”

Platform Opportunities

As the advertising market has become increasingly difficult for publishers they have looked to platforms for more significant revenue streams. Monetizing on platforms can mean several things. First of all in advertising, it can mean selling advertisers expertise and content of the type that performs well on social media. In other words, platforms offer media companies the opportunity to disrupt advertising agencies. BuzzFeed is the most obvious exponent of this approach. Its lifestyle verticals, such as the wildly popular food channel Tasty, are effectively all native advertising. But the language and presentation of what works on social has been learned from many experiments with editorial content (like, for instance, the gripping business of blowing up a watermelon).

With platforms also able to sell advertising more effectively, new options exist for revenue sharing. For instance on Google AMP—Google’s fast loading mobile page product—publishers keep all the revenue. On Facebook Instant Articles, the revenue for Facebook-sold advertising is 30 percent, unless the publisher sells the advertising themselves in which case it is 100 per cent. Snapchat strikes deals for revenue with publishers for upfront payment, though the terms of these deals do not seem to be consistent or standardized. Perhaps the most eye-catching of the platform opportunities was the direct incentive to publishers by Facebook to use its trumpeted Facebook Live video product. Here Facebook paid a small handful of publishers money to produce videos and paid news organizations up to $5 million each. The experiment came to an end at the end of 2016 and Facebook said it would no longer pay producers directly for live video.

Many publishers see opportunity for lasting revenue in using the greater reach of social platforms to help drive users and readers “down the funnel” towards becoming subscribers on a publisher’s own site. We notice a large uptick in the use of Apple News for instance after the release of iOS10 allowed news organizations to integrate subscriptions.

[visualizer id=”65847″]

Publishers: Too Little, Too Slowly

Digital Content Next, the body that represents digital publishers, published a survey at the beginning of 2017 that showed that the average publisher received $7.7 million, or, 14 percent of their overall revenue, from native platform experiments. To go from zero to 14 percent of revenue in a two year period suggests that this could become a very significant part of news organizations’ revenue if it grows at a reasonable rate. However, the revenue does not account for extra costs that can be very significant, particularly for producing a Snapchat Discover channel or a large number of Facebook Live videos.

Of all the products released by technology companies to help news organizations publish through their technologies, the most anticipated was Facebook Instant Articles. By the end of 2016 many publishers in our interviews were disappointed with the return on investment from Instant Articles and some, like The New York Times, abandoned them altogether.

“I’m in the same place I was before,” says Kim Lau, Senior Vice President & Head of Business Development of The Atlantic, describing her hope that more than a year on Instant Articles would yield some clarity on its value: “We have no reason to believe that Instant has been bad for us, but we still have no reason necessarily to say that it’s been a positive” (though she is more optimistic with the recently announced Facebook Journalism Project). She added, “Part of what I’m giving up is the ability to do the recirculation efforts . . . to try and get readers to sign up for other things, to sell them subscriptions.”

In crafting a relationship with news publishers, it is not surprising that the largest areas of contention are those over return on investment. Interviewees in publishing are still unclear whether the efforts to share revenue with them are worth the long-term trade-offs of losing control of brand, of audience data and relationships.

There is a range of benefits publishers can derive from using social platforms, but these vary between platforms, making the strategic approach to adoption a more complicated equation. As one local publisher said, “sometimes what optimizes to one platform goes against what would optimize for another one.” Our research showed we are seeing the end of singular social media strategies in newsrooms, as multivariate approaches increase. In our interviews, for example, it became clear that Snapchat is understood by publishers to be a resource-intensive way to build a brand recognizable to young audiences, and that Instant Articles are a way to reach wider audiences easily, but not profitably.

Whitney Dawn Carlson, the former social media editor for the Chicago Tribune, spoke of the struggle for news organizations to not only define but agree on what represents return on investment. “It’s building community, that’s what social media is. And the higher-ups just don’t get it, because [some platforms are] not bringing pageviews and money,” adding, “it’s a very print mentality.”

While the costs of producing high quality journalism for distribution cut into publishers’ platform profits, distributors of fake or misleading content can make tens of thousands of dollars on stories that take seconds to churn. At the benign end this means human-interest stories—or these days more often animal-interest stories. But at the other end of the spectrum, it means stories can be successful by playing on fears or partisan allegiances, and exaggerating or even fabricating for effect. Jestin Coler is a 40-year-old father of two living in California who set up Disinfomedia.com as a shell company through which to proliferate fake news sites, like Denverguardian.com. What started as an exercise by a registered Democrat to expose and “infiltrate the echo chambers of the alt-right” with totally fabricated stories ended with the same false stories spreading like wildfire. They were adopted as true by partisan groups who did not care whether the stories were true or not, and Coler could earn between $10,000 and $30,000 in advertising in one month.

The mechanics and architecture of platforms such as YouTube and Facebook have provided a rich breeding ground for these types of cheaply produced content. Facebook and Google have both shown concern about how much trashy automated or deliberately made up content is being generated by random individuals because of the financial incentives attached to them. But the same financial system that incentivizes low quality, sensational, or made-up pages in exactly the same way it incentivizes serious reporting is inevitably going to find itself overrun by the former.

The Publishers’ Dilemma

The opacity of the markets within all of the platforms, the unreliable metrics and the possibility that the rules for compensation might change at any moment without warning, are all reasons for publishers to be investing aggressively in finding revenues that stand apart from the technology players. However, we did not see the desire many publishers articulated to be more independent from platforms demonstrated by a wholesale withdrawal of their articles from social distribution. There was a glimmer of possibility that extra revenues might be available, for instance through Apple News, but the opposite was the case.

For companies such as BuzzFeed or NowThis News, there is no possibility of withdrawing from the platform distribution model, not least because it is intimately tied to their business models. The companies that live or die by the value of social media relationships are almost as vulnerable as those with a suboptimal media presence. The introduction and withdrawal of incentives, and the uncertainty of how distribution might continue to work, makes it particularly important for these organizations to be able to influence platform decisions.

Privately two views were expressed as to how some kind of equanimity might be achieved: The first would be a more coordinated approach to negotiation; the second that the platforms’ own competition will prove fruitful for news organizations. But the most popular content is not often the most expensive. In this environment serious news organizations have only one route open to them and that is to try and increase subscriptions or fees directly from readers. The native advertising model might work for some publishers, and a handful of business sites, like Quartz are confident they can remain profitable without relying on platforms for advertising revenue (Quartz is not on Instant Articles).

The development of a three-tiered support model—advertising, subscription, and not for profit—has seen high quality journalism become more reliant on non-advertising based models.

There are incidents of the pendulum at least temporarily swinging back towards news organizations wanting to redefine and consolidate their publishing status: the proliferation of membership and subscription services is both a route to solvency and independence for many. Exceptional brands in American journalism, The New York Times, The Washington Post, The New Yorker, BuzzFeed, and even CNN (although there are many who might balk at including cable news in this section), are far better placed in terms of safeguarding their own audience relationships and keeping their brand awareness intact within a fragmented market for attention. They can also invest in the technology and expertise to make better advertising products, and to keep pace with the platform developments too. Very few publishers have the resources that allow them to do the same.

The “pay to play” nature of the walled gardens of the mobile web is making it harder to start businesses in the “traditional” way for digital start ups, with writers, editors, technologists, and commercial staff. It is not impossible to build a new publishing enterprise, as experienced innovators like Mike Allen and Jim VandeHei of Axios have shown. It is still possible for new models to build ground-up businesses largely free of the influence of platforms. Examples such as the Silicon Valley subscription-only newsletter The Information, the stripped-down newsletter service TinyLetter, or podcasting businesses like Gimlet Media, are all fringe examples of innovative businesses which are creating products away from the control of social platforms. Many see a bifurcation of the market, between those businesses able to grow at scale, and those who are small enough to operate in niche markets.

Can Platforms Fix It?

The disappointment of digital ad revenue is pushing both platforms and publishers to rethink their relationships with subscription and membership payments. Social platforms and Google architecture were predicated to some extent on free or cheap information flows, without the impediment of subscription or paywalls. However, with increasing evidence in the market that subscribers are willing to pay news organizations for digital subscriptions, the attitude is changing. Even within companies like Google for which subscription has been anathema, there is an acceptance that developing subscription products might be the only way for news providers to earn adequate revenues.

The shift towards more controlled environments away from the highly dynamic world of distribution is a trend in platforms as well as publishers. Snapchat’s $24 billion IPO is essentially supporting a more traditional media model, of very restricted access to certain formats, an advertising platform that is more linear and a mitigation of publishing risk by making sure everything disappears without trace once it has been published.

The Snapchat formula is unproven as a sustainable business model, it has not yet shown a profit, but it points a much clearer way in which platforms might pick the winners among publishing brands, only allowing those that it favors onto its closed, exclusive platform, dictating publishing frequency and setting performance targets. In effect, Snapchat Discover shifts the powers associated with publishing entirely under its own control.

In early 2017 Facebook announced it would recalibrate the way Instant Articles worked in order to deliver more revenue back to publishers. At the time of publication, there were few details on what this might look like.

When Facebook launched Instant Articles in 2015, Michael Reckhow, the then product manager, described a utopian way forward for publishers to work with Facebook—to offload the costs of advertising sales and production tools and just concentrate on editorial. Publishers who need to be self-sustaining are looking at how to slash costs and restructure their newsrooms. If the financial incentives were adequate, Facebook might see the ambitions for their publishing product realized more quickly.

Time and again in interviews with platform executives, there was a genuine enthusiasm about how to elevate better journalism. Uncertainties aside, publishers throughout our interviews spoke positively about new storytelling opportunities and the ability to reach new audiences or engage existing audiences in a new way.

The platforms are also changing the way that newsrooms think about the work they produce, which, despite its problems, is not always an unwelcome change:

One of the good things about the Google and the Facebook changes is that they forced everybody to start thinking about speed where nobody was thinking about it before. And page performance and user experience, like those are things that are becoming fundamentally part of the core way that publishers are thinking about growing and presenting their content and then a couple of years ago we rarely talked about the user and how much we wanted them to think about their needs versus our own.

—Kim Lau, The Atlantic

At the outset of the research there was a cautious optimism if Facebook could really sell advertising more efficiently, then that would be welcomed.

But there is also a strong sense of disconnect. Publishers have existential anxiety about the migration of audiences to larger platforms that deliver all manner of things more efficiently.

After all, one of the elements of journalism that the platforms do not do, and say they will never do, is reporting. And social platforms have vastly aided in the resources available to reporters. Some of the most effective reporting in the 2016 campaign came from reporters like David Fahrenthold of The Washington Post who was able to use his social following to help him investigate the use of Donald Trump’s Foundation funds, or Craig Silverman, media editor at BuzzFeed, who has uncovered the prevalence of fake news and changed the political agenda as a result.

But good reporting is not currently algorithmically privileged on many platforms. Not on Facebook, not on YouTube, not on Instagram, not even on Twitter—although its open environment does allow it to be elevated within informed groups. If the political events of 2016 and the concurrent and subsequent reporting on the issues proved anything, they proved that the failure of platforms to ‘edit’ themselves could lead to widespread damage. The plausible deniability of platform companies that they are not in the business of publishing is at an end.

The evolution of this relationship points to a critical question for news organizations. Is publishing going to remain a core activity that supports journalism, or will it over time, migrate more fully into the fabric of technology and hosting companies?

It is entirely possible that what it means to be a news organization might be increasingly defined in terms that stand apart from monetization, hosting, and even the development of formats, and is expressed instead in terms of the tone, content, and community around reporting.

The present anxiety is that for the rest of journalism, this will not be possible, and that any level of sustainability that serves every segment of the market with at least some durable and useful news, particularly in smaller markets, will shrivel or perish. In mid-sized and small local markets this is already happening.