Executive Summary

This research report explores archiving practices and policies across newspapers, magazines, wire services, and digital-only news producers, with the aim of identifying the current state of archiving and potential strategies for preserving content in an age of digital distribution. Between March 2018 and January 2019, we conducted interviews with 48 individuals from 30 news organizations and preservation initiatives.

What we found was that the majority of news outlets had not given any thought to even basic strategies for preserving their digital content, and not one was properly saving a holistic record of what it produces. Of the 21 news organizations in our study, 19 were not taking any protective steps at all to archive their web output. The remaining two lacked formal strategies to ensure that their current practices have the kind of longevity to outlast changes in technology.

Meanwhile, interviewees frequently (and mistakenly) equated digital backup and storage in Google Docs or content management systems as synonymous with archiving. (They are not the same; backup refers to making copies for data recovery in case of damage or loss, while archiving refers to long-term preservation, ensuring that records will still be available even as formatting and distribution technologies change in the future.)

Instead, news organizations have handed over their responsibilities as public stewards to third-party organizations such as the Internet Archive, Google, Ancestry, and ProQuest, which store and distribute copies of news content on remote servers. As such, the news cycle now includes reliance on proprietary organizations with increasing control over the public record. The Internet Archive aside, the larger issue is that these companies’ incentives are neither journalistic nor archival, and may conflict with both.

While there are a number of news archiving technologies being developed by both individuals and nonprofits, it is worth noting that preserving digital content is not, first and foremost, a technical challenge. Rather, it’s a test of human decision-making and a matter of priority. The first step in tackling an archival process is the intention to save content. News organizations must get there.

The findings of this study should be a wakeup call to an industry fond of claiming that democracy cannot be sustained without journalism, which anchors its legitimacy on being a truth and accountability watchdog. In an era where journalism is already under attack, managing its record and future are as important as ever.

Local, independent, and alternative news sources are especially at risk of not being preserved, threatening to leave critical exclusions in a record that will favor dominant versions of public history. As the sudden Gawker shutdown demonstrated in 2016, content can be confiscated and disappear instantly without archiving practices in place.

Key findings

- The majority of the news organizations that participated in this research (19 of 21) had no documented policies for the preservation of their content—nor did they have even informal or ad-hoc archival practices in place.

- In addition to the failure to archive published stories from their own websites, none of the news organizations we interviewed were preserving their social media publications, including tweets and posts to Facebook, Instagram, or any other social media platform. Only one was taking the steps necessary to tackle the problem of archiving interactive and dynamic news applications.

- Digital-only news organizations had even less awareness than print publications of the importance of preservation. A persistent confusion that backing up work on third-party, cloud servers is the same as archiving means that very little is currently being done to preserve news.

- When we asked interviewees why they believe news organizations are not archiving content, they said repeatedly that journalism’s primary focus is on “what is new” and “happening now.” Journalists and their news organizations are more interested in preserving documentation of their reporting and what makes it accurate than preserving what ultimately gets published.

- As a result, platforms and third-party vendors, which increasingly host news content on their closed servers, are in control of the pieces necessary for holistic preservation without the journalistic incentive to enact it.

- Staff at news organizations often cited relying on the Internet Archive, a nonprofit digital library that maintains hundreds of billions of web captures, to preserve their own publications—even though web archiving has limitations around the formats it can capture and and preserves only a fraction of what is published online.

- News apps and interactives, in particular, are at high risk of being lost because often the new technologies they are built on become obsolete before anyone thinks to save them. Newsroom developers and emulation-based web archiving tools under development can be valuable allies in preserving these and other resources in jeopardy.

- There exist a number of other archiving initiatives, by both individuals and nonprofits, from which news managers can learn or enlist services, including PastPages by Ben Welsh, NewsGrabber by Archive Team, and Archive-It by the Internet Archive. According to news organizations, for digital archiving efforts to succeed, the process must be made simple, both in terms of implementation and workflow.

- Partnerships among archivists, technologists, memory institutions, and news organizations will be vital to establishing best practices and policies that assure future access to digitally distributed news content. Collaboration between all parties should begin with two questions: What should be preserved? Who should preserve it?

- Creating robust digital archives will mean grappling with tough questions, like how often to capture a copy of an ever-updating home page, if personalized content and newsletters should be preserved, and what to do with reader comments and social media posts.

- To enact lasting change, it will be key to find opinion leaders in the field to help introduce archiving ideas in a way that makes sense to staff, as well as to those in management positions who must ultimately be convinced of its advantages and compatibility with their priorities.

Introduction

The process of producing print journalism, particularly between about 1950 and 1990, consisted of a set of steps worked out over decades, which began with the reporter discovering a story and ended in distribution to the public. A single media organization handled most of the steps involved in production, including archiving. At a good number of newsrooms, an in-house librarian was a stop in this production pipeline, guaranteeing some level of future access by clipping individual news stories from the newspaper and filing them on-site according to subject keywords in a morgue (a physical space allotted to the clippings).

Back issues of whole newspapers were also frequently kept on-site in multi-story buildings. Librarians at selected news outlets negotiated contracts with ProQuest and other commercial information companies to microfilm their publications. Those—or original print versions if they bypassed the microfilming step—landed with the Library of Congress. Even less systematic and complete, broadcasters kept basic records of past radio and TV news programs, if not entire episodes, on tape along with a succession of other media. News wire services managed printed versions of wire stories based on their own internal criteria.

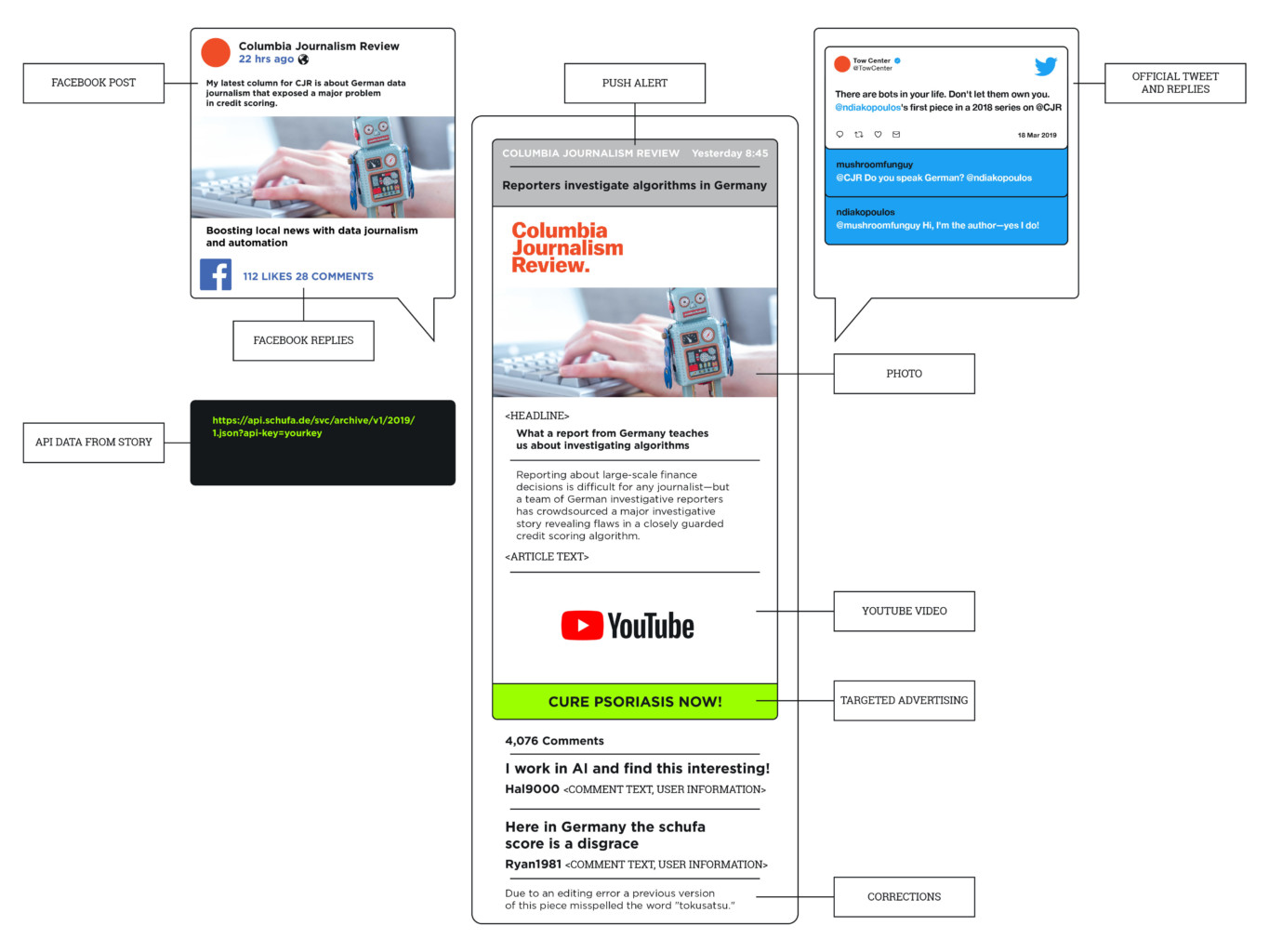

This infrastructure began to break down by the mid-1990s with widespread adoption of the internet and the multifaceted production of online news. Today, a news product often consists of no fewer than a half dozen elements, including a headline, byline, text, and images, as well as comments, interactive features, embedded video, and outgoing links. In addition, a reporter or editor will post links to stories on external sites such as Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and other third-party platforms. While the internet has created a vibrant information infrastructure, very little digital content is archived and former models can no longer guarantee long-term access. Although some news workers recognize the risk of losing content, they continue to rely on a content management systems (CMS) or cloud-based servers to store their work, practices they confuse with preservation and that we argue are not the same.

This report extends previous scholarships and surveys that provide an indispensable context for examining the digital infrastructure which now defines news production, as well as the role the internet plays in archiving practices and policies. For example, having a dedicated person responsible for archiving can be one of the most decisive factors in whether something is saved for the future, according to the book Future-Proofing the News: Preserving the First Draft of History, a formative examination of media preservation efforts over the past 300 years that captures the cultural and systemic issues involved.1

In stark terms, former newsroom librarians Kathleen A. Hansen and Nora Paul detail the infrastructure that makes up news preservation, including digital capture of newsprint on microfilm. While this is a pervasive practice that news organizations and cultural institutions may believe is a good alternative to archiving, the authors note, “the notion of a ‘preservation’ version of anything in digital form is highly problematic.”

In the same vein, “Missing Links: The Digital News Preservation Discontinuity,” connects current challenges to an institutional history that has not prioritized preservation.2 The 2014 report and accompanying survey follows the development and management of news archives from morgue to born-digital repositories, looking along the way for evidence of intention to preserve. Its authors found little, writing, “While the marketplace rewards breaking news, managing previously published news content has historically been someone else’s problem, most often a librarian’s.”3

Together with archivists and preservationists, librarians have been those most concerned with safeguarding the newspaper as a cultural record, the report argues. Librarians were replaced by automated information retrieval systems and services, including electronic news libraries, commercial databases, and “electronic morgues” compiled from newspapers by private companies.4 Computer automation increased in the newsrooms, and with reporters able to access information independent of news libraries and their keepers, the role of librarians diminished, according to this account.

Around this time local papers and some large metros stopped clipping. After successive layoffs and buyouts over the past several decades, few librarians continue to work in newsrooms. Because they no longer oversee the preservation aspects of the news organization, decisions are left to newsroom staffs, including reporters, editors, and executive management who do not often recognize the historical value of news content.

The pace of digital news is fast and stories are continually updated. Journalists are unlikely to slow down to look backwards at what was published yesterday when, in the words of the editor of a daily, “momentum is always forward.” It’s even less likely when they have to figure out which version of the story to save, and whether to include photos, interactives, and databases. This presents an important point of failure.

In best-case scenarios, newsrooms that dismantled their morgues or libraries donated the materials to historical societies or libraries instead of discarding them. However, the collections may be incomplete, as clips have been stolen or mishandled. The content that remains may be available on microfilm, in which case it can be digitized—if funding is available. While we found that it was not uncommon for news organizations to have digitized versions of newspapers covering most of the 20th century and even mid- to late-19th century, they had little or nothing from newspapers published in the 21st century.

While in 2011 the Center for Research Libraries mapped out the ways that the digital environment was affecting news preservation,5 in 2014 the Journalism News Archive Project began organizing a series of forums called “Dodging the Memory Hole” at the University of Missouri’s Reynolds Journalism Institute.6 A collaboration between scholars, activists, archivist, librarians, journalists, and technologists, the project organized forums focused on strategies, models, and ways to raise awareness about the importance of digital news preservation.

Digital archives can easily become obsolete due to evolving formats and digital systems used by modern media, not to mention media failure, bit-rot, and link-rot.

The name of the initiative comes from George Orwell’s 1984, in which photographs and documents conflicting with Big Brother’s changing narrative were tossed into a “memory hole” and destroyed. According to the founder of the Journalism Digital News Archive, Ed McCain, today’s memory hole is largely the unintentional result of technological systems not designed to keep information for the long term. In digital newsrooms, he added, a software/hardware crash can wipe out decades of text, photos, videos, and applications in a fraction of a second. Digital archives can easily become obsolete due to evolving formats and digital systems used by modern media, not to mention media failure, bit-rot, and link-rot. As part of “Dodging the Memory Hole,” McCain organized a series of events that brought together media companies, memory institutions, and other stakeholders committed to preserving, as the site put it, the “first rough draft of history” created in digital formats.7

In her 2015 article “Preserving News Apps Present Huge Challenges,” Meredith Broussard characterized news apps—interactive news applications, pieces of born-digital journalism, or software that has been custom-built to tell a story—as an understudied challenge to preservation, one more ubiquitous and insidious than the fragility of high-acid newsprint.8 She describes them as characteristically stand-alone pieces of software, interactive and exploratory, that create an experience which could not have been built under the constraints of a conventional content management system. These features distinguish them from other born-digital news content and make them especially difficult to archive and preserve. Understanding the scope of the problem is in itself difficult.

Priorities and criteria for preservation are lacking in part because efforts to document the number and nature of news apps, as well as assess how many have disappeared or are in need of preservation, have been incomplete. News apps also present additional and daunting challenges beyond the legal, technical, and financial ones that have dogged preservation of print and online content. This puts many terabytes of born-digital news content at risk of being lost to the “black hole of technological obsolescence,” as Broussard and fellow researcher Katherine Boss have said elsewhere.9 As we detail in this report, the answer is to emulate the environment for which apps were originally created so they can be played back in the future.

Educopia, an institute that fosters collaboration between libraries, museums, and other cultural memory organizations to advance archiving efforts, also contributed to the efforts at facilitating digital preservation with the 2014 “Chronicles in Preservation” project.10 The report provided information about strategies, workflows, and tools that would make news content preservation-ready for a repository, and compared technical approaches MetaArchive-LOCKSS, Chronopolis-iRODS, and UNT-CODA for digital archiving.

Despite differences in their methods and focus, such initiatives identify a lack of policy in the United States. Currently, the centerpiece of US policy for the preservation of newspapers primarily revolves around copyright of print newspapers. Otherwise, where policy exists, it is variable and selective. Overall, very few back issues of the nation’s newspapers can be obtained in digital form except for a few large metro dailies such as The New York Times and national magazines that provide access through their websites.

Otherwise what is available is dispersed across newsrooms, heritage institutions, and commercial providers including, increasingly, Google. This leaves out a vast range of publications, including reporting by communities of color and LGBTQ groups, alt-weeklies, and newsletters that newsrooms are now using to circumvent the platforms’ influence on distribution. Interestingly, we spoke to one alt-weekly that carefully managed print content but paid no attention to preserving stories it published online.

In his 2018 book, Networked Press Freedom: Creating Infrastructures for a Public Right to Hear, communications scholar Mike Ananny examines how news organizations may work against preservation by taking advantage of the very features that put digital content at risk.11 He describes how U.S. News and World Reports deleted much of the content it produced before 2007 after switching to a new content management system. Likewise, he notes that BuzzFeed erased more than 4,000 articles in 2014 that no longer matched new editorial standards. Both incidents set off public concerns over a news organization’s attempt to alter its past and, by extension, the public record.

News workers we interviewed frequently cited the case of Gawker, which we discuss elsewhere, as a cautionary tale illustrating the precarity of digital news. Gawker’s shutdown12 prompted an effort by the Freedom of the Press Foundation and the Internet Archive to collect at-risk news sites in a repository called “Threatened Outlets.”13 But news preservation has long bedeviled the industry and cultural heritage institutions. As a consequence, the findings in this report are consistent with previous scholarship highlighting the institutional, organizational, political, and technological facets of news preservation. We build on previous work by examining the growing role of platforms in the news publishing infrastructure, as well as the changing infrastructure of the web as APIs (application programming interfaces) become commonplace, further loosening publisher control over their content and prompting the question of how to preserve that which is dynamically accessed from an external site.

Previous Tow Center research identified an uneven power balance between publishers and platforms, noting that “platforms increasingly weird more power over formats and data, including publishers’ editorial strategies, distribution strategies, and workflows.”14 Google provides one example of this trend as the platform continues to expand into journalism with deals between Google Cloud Platform and Telegraph Media Group,15 as well as manage millions of photos for The New York Times.16 However, the ways in which this affects the long-term historical record has not been addressed, and it continues to evolve.

Social media presents a highly unstable form of news that is poorly understood by news workers, who rarely can account for the breadth of what they publish on platforms. They also overlook that, while its news value will continue to be debated, social media belongs to the platforms. Tech giants can simply flip the switch, causing all traces of platform-centric, strategic publishing agreements—which no doubt shape priorities and editorial values17—to vanish. Of course, some news organizations might prefer that state of affairs; meanwhile, historians, scholars, and researchers will lose evidence of how audiences once engaged with news organizations online.

In short, newsrooms are currently doing very little to nothing to preserve digital news. That being said, our jumping-off point begins with the acknowledgement that newsrooms are still adjusting to digital news (albeit badly), and that digital-born content is not simply ephemeral, it is multifaceted, unstable, and malleable. Rather than a crisis that can be solved by technology, we understand the problem to be structural. Although technology can assist in digital preservation, human action is the first imperative. We devote, for this reason, the first section of this report to the perceptions of preservation that the news workers we spoke with expressed to us.

The section following then outlines the intricacy of digital news preservation, while the one after discusses those people and collectives making active progress in the field. Finally, the appendix provides additional archiving resources for newsrooms. In this spirit, we also offer this report as a tool for discovering new ideas about maintaining news in any medium for the future.

Methodology

This news archiving research project began in November 2017 at Columbia Journalism School and was conceptualized at the Platforms and Publishers: Policy Exchange Forum IV at Stanford University, hosted by the Tow Center for Digital Journalism and the Brown Institute for Media Innovation. The one-day conference entitled “Public Record Under Threat: News and the Archive in the Age of Digital Distribution” discussed the importance of news preservation in the digital age and included audience members from the journalism community, as well as archivists and librarians.18

The main research questions that drove our work herein sought to examine the practices and policies of archiving at news organizations. Along this line of inquiry, we asked questions such as: How are news organizations saving content including print, digital-born, social media, multimedia, as well as video, images, and sound recordings? What is their workflow? What technologies are they using, if any?

Another line of examination focused on the decision-making process. Who are newsrooms consulting about archiving strategies, and how do these consultants shape strategies/models? How do they perceive the importance of preservation, and what technology do they use for the preservation? What are policies for preservation within and across platforms? Where do the responsibilities of journalist, publisher, programmer, and consultant begin and end?

For the purpose of our research, we created a list of US-based media outlets that represented a variety of scale and formats, and which was far larger than what became our pool of willing interviewees. We then added to the list professionals and experts in digital preservation, in general, and news preservation, in particular. For example, we included the Internet Archive because of its central role in preserving news content. We also included private companies and vendors which offer services for newsrooms that include preservation and archiving features.

In March 2018 we started to schedule interviews. We introduced ourselves as researchers from Columbia University and fellows at the Tow Center for Digital Journalism. Between March 2018 and January 2019, we conducted interviews with 48 individuals from 30 organizations. Of those, 21 interviews were with staff members at news organizations, three interviews were with memory institutions (such as libraries), two interviews were with tech companies offering archival services for news organizations, and five interviews were with professionals working and studying the issue of news preservation. For the majority of the news organizations in our sample, we interviewed more than one staff member. In some cases, we interviewed as many as four staff members together, at the same time.

We asked them to tell us about the challenges and opportunities related to preserving news content. Finding the right person at the news organizations was difficult. We started by asking if there was a position for a news librarian at the organization. If there wasn’t a news librarian, we asked for help locating a suitable person to tell us about archiving and content preservation at the organization. In many cases, this person turned out to be someone in a high editorial position. In other cases, we were referred to the research department or to the person in charge of what was left of the morgue and clip files. Since we asked all of the participants to meet us in person, in many cases they asked for initial contact by phone.

We promised the participants anonymity. When anonymity was not feasible, as in the case of the Internet Archive, we asked permission to use the name of the organization. Otherwise, all names and identifying information were anonymized and kept confidential, and their responses are not identifiable in the report.

The majority of the interviews we conducted were in person. In the cases when this was not possible, we conducted video or phone interviews. Interviews lasted between one to three hours. The conversations were semi-structured and centered mostly around preservation and archiving practices and policies. With the consent of the participants, all the interviews were recorded and transcribed. We preserved all copies of the recordings, encrypted on our own personal computers. We analyzed the data with thematic analysis qualitative research methods. First, we read transcripts of the interviews and identified several themes that appeared in the majority of the interviews. Perceptions about the value of news and its preservation, which we discuss in the following section, was a major one.

Perceptions of News Preservation

In this section, we discuss some of the common perceptions regarding news content preservation and news archives as reflected in the interviews we conducted with the staff of news media outlets, libraries, and archive initiatives. Identifying these common ideas can be the first step toward raising awareness around both perceptions and misconceptions about news archives and the preservation of news content.

“If it’s in a Google Doc, it’s sort of there forever. Right?”

The majority of the participants we interviewed reported that they rely heavily on cloud services, particularly Google Docs and Gmail in their daily work. The adoption of platforms in the newsroom aligns with previous studies, which conclude that platforms and tech companies are involved in every aspect of journalism.19 While the nature of the relationship between publishers and platforms has been widely discussed with regard to the distribution of content, advertisement revenue, and the need to optimize search engine performance, these studies overlook the ways in which newsrooms rely on the tools and services provided by digital platforms for backup and content storage.20

Some of the participants we interviewed expressed their concerns about relying on Google or Amazon, sharing that the decision to use these services had been discussed and reviewed in editorial meetings. For example, one issue that came up in our interviews was that when reporters leave a news organization, they retain ownership of those Google Docs they created and can thus revoke sharing privileges, making content inaccessible to others in the newsroom.

Despite these concerns, most interviewees focused more on the productivity allowances of these services, mostly ignoring the implications of relying on platforms to store news content and those around the control of data.

Since most correspondence in newsrooms is conducted through digital platforms, and news content is published mostly in a digital format, the reliance on cloud services seemed almost natural to editorial staffs. The practice of actively archiving news content to ensure that it will be available for the long-term future, practices once performed by news librarians, seemed redundant to interviewees because, “if it’s on Google Docs, it sort of there forever.” This response, which we heard from many participants, reflects not only the organizational changes of a news industry that’s seen news librarians and archivists let go during successive rounds of layoffs,21 but also how staff at news organizations perceive their own personal responsibility (or lack thereof) in preserving the stories they publish.

When we asked about the news content published on social media, the most common response was that it is being preserved by Facebook, Twitter, or Instagram. One person affirmed, “We’re not archiving our own tweets or anything like that. If Twitter decided to go out of business tomorrow and shut down their databases, we’d lose all that.”

Although very few worried that Google might not exist 10, 20, or 30 years from now, almost all of the participants shared with us personal stories and experiences of losing information. In one interview with a nonprofit news organization, the publisher described losing access to an old email account as profoundly traumatic. A magazine editor trying to access stories written a decade earlier said they had just “disappeared.” Another editor cited concerns over interactive content published five years ago that did not work anymore.

Even though the experience of losing content came up in nearly all of our interviews (and in some cases multiple times during a single interview), when we asked what the participants had done to prevent information loss from happening, few had an answer. In other words, they had not taken any steps to minimize the loss of news content in the future despite a keen awareness that digital news is inherently challenging to maintain.

In one interview, an investigative editor working for a digital outlet described detailed efforts to painstakingly document as evidence all the steps involved in their reporting, including paid tracking software and documenting devices. In the end, they did not save the published story. When asked why not, they said because“it’s been preserved on the website.” Likewise, none of the content creators we spoke to made an effort to download the stories they wrote (or edited) and preserve them in a separate file on their personal storage devices. Instead, the majority rely on their news outlet websites, a CMS, or Google to retrieve old articles.

The challenge of preventing digital content loss was raised only in relation to personal experiences and not as an organizational obstacle that needed to be addressed. This disconnect between the understanding that, absent active preservation efforts, digital information is prone to disappear stood out in all the interviews we conducted.

“News is about what is new and now, in the present, and not about the past”

Given the lack of preservation policies in place at the majority of news organizations that participated in our research, finding the right person to interview posed a challenge. Out of the 21 news organizations, only six employed news archivists or librarians. None of the digital-only outlets had a news librarian or archivist on staff. When those positions did exist, they included additional responsibilities, taking the focus away from the work required for preservation. Furthermore, most people we talked to associated archiving with print news.

Digital news outlets think differently about preserving content than organizations that are still publishing print editions. As an editor at a digital-only outlet explained, “The difference between digital-only and print organizations is that we try to keep everything in circulation. We don’t [have] to preserve things for the record. We have to keep the record publicly available.” In this editor’s view, the primary job of digital-only news organizations is to get fresh news content into circulation on the internet, where it can be found by anyone looking.

While those outlets that publish a print edition seemed more attuned to preservation and the stewardship of the news, digital-only publishers often conceived of their companies as content-generators whose work had limited long-term value and life span. As an editor at a leading news organization told us, “In the worst-case scenario, we will always have our papers as evidence.” Those companies that produced print editions were also more likely than digital-only outlets to cooperate with third-party vendors such as NewsBank, a database company that provides archives of media publications as reference materials to libraries.22

It quickly became clear that staff at news organizations did not believe it was their responsibility, as reporters or editorial staff, to preserve content for the future.

When we asked why news organizations are not preserving digital content, we heard the same answers from most: reporting and producing news is about what is happening now, while archiving and preservation was perceived as an act of the past. “Archives are all about old news,” one person said.

It quickly became clear that staff at news organizations did not believe it was their responsibility, as reporters or editorial staff, to preserve content for the future. One editor explained it to us this way, saying: “Who cares what existed 10 years ago? I need my thing now. And so, for better, for worse, if there was some value in [archiving], I probably got a better value out of the new thing.” In other words, journalists’ time is better spent working on short-term needs and news cycles rather than ensuring access to historical content in the future.

The addition of data science professionals in the newsroom and the influence of Silicon Valley startup culture on the journalism profession has no doubt informed this attitude. One data editor told us:

I just think that it is part of the ethos that things are disposable, sites are disposable. If I didn’t treat some of our sites as disposable or our apps as disposable, I would kill myself. I mean trying to keep this stuff running . . . we do have to just let stuff go. Don’t get me wrong, I love history but it’s not on my priority list.

One significant outlier in the digital news archiving arena is The New York Times, which is currently working on building out its own web archive at https://archive.nytimes.com. Its aim, the site notes, is to preserve “the original web presentation of articles” and interactive projects “for posterity” by hosting “a copy of the HTML of NYTimes.com pages from when they were first published.”23 This is an effort, it should be emphasized, that has required careful consideration among staff around defining specific goals for archiving.

In 2018, when the newspaper moved to a new version of the system that had long powered its website, senior product manager Eugene Wang told Nieman Lab: “There was one path we could’ve taken where we’d say: We have all these articles and can render them on our new platform and just be done with it. But we recognized there was value in having a representation of them when they were first published. The archive also serves as a picture of how tools of digital storytelling evolved.”24

Archive versus Backup

Multiple participants reported having backups of story versions, though they are not available to the public. Many interviewees, however, were unable to distinguish between these backups and an archive, or note the difference between storage and preservation. This confusion stood out in the majority of our interviews. It was evident that participants perceived Google Docs, Amazon cloud servers, or their company’s content management system as equivalent to archives, rather than as mechanisms for storage. Given the focus we heard about the present—about what is new—combined with the Silicon Valley emphasis on iteration now increasingly common in newsrooms, the lack of distinction between backups and archives did not surprise us.

However, the difference between the two is an important one. As the literature about digital preservation for archive libraries and museums illustrates, backups maintain continuity of an organization and the ability to recover and restore information, rather than ensure long-term access. Backup strategies do not take into account potential future hazards such as obsolescence of hardware, outdated data formats and storage media, or obsolete software. Therefore, while backup and recovery strategies are a key component of adequate archiving, backing up information is not enough to ensure ongoing access and cannot be considered an archiving policy.25

The confusion means that not only is very little being done currently to preserve the news, but also that the prospects for the survival of some of the most significant reporting published online today are shaky. In the past, people had faith that paper or microfilm copies would survive, even if a news organization did not. In contrast, when asked what digital content they believe will still be available in 20 years, few interviewees were optimistic. In the words of one chief editor, “I am not sure we are prepared for the day that [name of the news organization] is no longer a thing.”

When asked to conceptualize what archives should be, participants were unsure and conflicted. One editor described archiving as the “preservation of editorial intent or preservation of fidelity.” That is, it’s more than a technical feat, but is rather a challenge to maintain the integrity and context of the publication. In a different interview, an editor of a digital-only news outlet referred to the question of archiving content on the internet as philosophical, asking if it’s even possible to preserve an experience. For them, the web is so much more dynamic than television or print is to news consumers.

Our interviewees are not alone in their estimations about the significant issues associated with archiving from the web. As Hansen and Paul told us, “It’s like nailing smoke to the floor. No one can do it, and they are not even sure they want to or need to do it.” But just as web archiving raises theoretical, philosophical, and methodological challenges, the first step in tackling the process is the intention to save content. Most news organization not only lack the interest, but are unsure if archiving digital content is even possible.

Archive.org

The majority of the participants mentioned using archive.org, also known as the Internet Archive (IA) or the Wayback Machine,26 to find content that was no longer available through a search engine or on a publication’s website. When we asked about a specific story or content that had disappeared, the common answer was: “It is probably available at archive.org.”

Some interviewees cited the Internet Archive not just as a tool that they use in their journalistic work, but also as a model for how to archive online content and preserve the news. We repeatedly heard, “Thank God for the Internet Archive.” This reverence was certainly in part a result of a recent series of attempts by high-profile people and publications to delete websites and social media, raising the profile of the Internet Archive for journalists and casual internet users alike.27 But the organization is also the recognized industry leader in digital preservation, dwarfing other initiatives. Founded in 1996, the Internet Archive envisions itself as a modern-day Library of Alexandria, providing “universal access to all knowledge.”28

The organization’s founder, Brewster Kahle, was an early proponent of digital preservation and started the organization to, in his words,“archive the internet.” As a result, the majority of what the organization collects is digital. The main mechanism for that collecting is a procedure called crawling, similar to the way Google “crawls” and indexes the web.

The Wayback Machine is the main tool that researchers and journalists use to retrieve information, including content taken down, whether intentionally or accidentally. It was even referenced in Congress during Mark Zuckerberg’s recent testimony when North Carolina Senator Thom Tillis called it a “history grabber machine.”29

The significance of the IA for online journalistic work cannot be underestimated. Newsrooms are not only relying on the organization to preserve evidence for their reporting, but also to preserve their own published content. This is engendering a dangerous and false sense of security. First, as scholars point out, the Internet Archive does not follow traditional archival practices such as standards for description and organization of archival materials.30 Second, and more importantly, the IA does not preserve everything.

For one, preserving the entirety of digital news content is an immense responsibility that no single organization or technology can meet. An IA staff member told us, “People ask me all the time, ‘did you have a backup of my site?’ And I say, ‘I have no idea. I can tell you what I backed up from your site, but I can’t tell you how that relates to everything that’s on your site, because I don’t know everything that’s on your site.’”

Even if the IA has captured a website, what it collects may be limited to the first level of content and could exclude links, comments, personalized content, and different versions of a story. Also, although the Internet Archive actively crawls sites, the nonprofit relies heavily on voluntary, non-staff contributors. As a manager put it, “We are actively looking for people to work with . . . we know we can’t do it by ourselves.”

Corrections and Versioning

Another issue that emerged in our interviews relates to article corrections and the publication of multiple versions of a story on the web. Corrections (such as a street name or more substantive information) to a news story are routine but tend to be limited. All interviewees reported that with every correction to a published story, they make sure to add a note specifying the change, always trying to make the process as transparent as possible for their readers.

Meanwhile, dozens of versions of a single story may be published in one day. Since most news organizations that participated in our research did not have a policy or procedure to ensure that their content is archived or digitally preserved for the long term, many interviewees expressed concerns regarding the evolution of stories and the ways in which it is difficult to retrieve previous versions. One person mentioned that in the case of a lawsuit, being able to access these versions would became important.

Some participants were confident they could access old versions from their CMS or server, even if the content was not made visible outside of the newsroom. Even so, nearly universally everyone admitted having lost content during the migration from one CMS to another, or because of a server crash. And in one case, content from an old-version CMS could no longer be accessed at all, emphasizing again how long-term preservation and archiving are not the same as backups and storage.

Deletion

Deletion is the opposite side of preservation. News organizations, in certain cases, actively remove content from the public record31—an act that raises questions about the role of journalism in society.

While interviewees reported deleting emails sent to the newsroom or phone messages left by readers for reasons ranging from cleaning space on their computers to protecting sources, most said that deleting published content is abnormal behavior in the newsroom. Receiving requests from readers to delete stories is, however, common. An executive editor at a digital-only organization said the issue has been exacerbated by a move from print to digital. “In the past, if your name was mentioned in the newspaper, then everybody read it. But later it was folded and forgotten or preserved on microfilm that people actively need to go and search for.”

Today, when people are searching for someone’s name on the internet, the editor said, “this article is the first thing they see,” adding, “and then again, the internet doesn’t forget.” News organizations generally reply to those requests by saying that they cannot remove content from their site, the editor told us.

Some participants did, however, report that they delete tweets. On Twitter, compared to other social media platforms, there is more of a tendency for deletion. “When the text was changed or misspelled, we delete it,” one person said But in cases of a more significant error, the majority of participants explained their efforts of transparency around any correction or mistake that was made. Another person said, “Our concerns are primarily with the here and now. We are more interested in making sure that misinformation is not being spread [on Twitter], or our reporting is not being used to further kind of disinformation. We’ve been known to correct a tweet or two.”

The Case of Gawker and Gothamist

Naturally, the story of Gawker and Gothamist drew a lot of attention in the journalism community. In August 2016, after losing in a lawsuit filed by former wrestler Hulk Hogan and filing for bankruptcy, Gawker.com shut down. Then in November 2017, after employees at Gothamist voted and won the right to unionize, billionaire owner Joe Ricketts announced shortly thereafter that they had all lost their jobs and that the site would cease to operate.32

Many participants talked to us about realizing right then that 10 years’ worth of work could disappear, as if it never existed. The fragility of digital content became apparent. In the days of print, one of the interviewees said, if a newspaper closed down, reporters could still access hard copies of their work. The case of Gawker and Gothamist highlighted how easily digital reporting can be made to disappear.

As of today, the Gawker website (including old stories) is still available,33 and in April 2018 Gothamist was relaunched thanks to funding from a consortium of public radio outlets.34 35 Even so, interviewees described the ability of a single person to effectively erase history as terrifying. The Gawker and Gothamist cases both scared reporters who don’t personally archive their own work, just as it demonstrated the role of news archives in democratic societies and the need for preservation policies that ensure the public with a faithful account of history.

The Intricacy of Archiving Digital News

Whereas news was originally received as a finished product, delivered or broadcast to audiences, production now continues in a seemingly never-ending cycle. Instead of on industrial printing presses, news is produced in bits and bytes in content management systems like WordPress and distributed on the internet. News is increasingly dynamic, interactive, and personalized. In comparison, the newspaper seems almost frozen.

“The web, however, is not,” one news librarian told us. “It’s constantly changing and being updated.” But while the internet is often implicated in the troubles of today’s news industry, many of the developments discussed here transcend media formats, affecting both print and digital-only publishers.

Control and Care

Since the 1980s, newspapers have been contributing to searchable commercial databases, eliminating conventional clip files and the personnel hired to maintain them. Those automated information retrieval services have expanded over the years. The most prominent vendors include ProQuest,36 NewsBank,37 and Gale38—and nearly every news organization interviewed had a contract with one of them. Many used their services as a commercial database. A select number of newspapers also contract with one of these vendors to receive microfilm or e-print (i.e., PDF) versions of newspapers that are then distributed to the Library of Congress according to regulations and/or for copyright purposes.

Another database with a growing role in maintaining historical collections, including news,39 is Ancestry.com, the largest privately owned genealogy company in the world. In addition to acquiring Archives.com and its digitized collection of newsprint in 2012,40 the company began hosting the content on a stand-alone site it owns called Newspapers.com, which claims to be the largest online newspaper archive with more than 11,000 newspapers and 43 million pages from the 18th century to today.41 It adds new pages (millions each month according to company promotional information) by scanning publications accessed through partnerships with libraries, publishers, and historical organizations for free, bypassing the Library of Congress and other public programs.

Newspapers.com provides the archived news content to subscribers for family history research and to its partners, including the New York Public Library42 and Brooklyn Public Library.43 The closest competitor is NewsBank.com, which news outlets use to host articles behind a paywall. Staff, including newsroom librarians we spoke to, welcomed the arrangement because it provided otherwise expensive digitization services for free. “It’s the last place that funding goes. So, it’s always kind of a struggle to keep these systems going,” the sole news librarian at a mid-sized newspaper said, referring to digitizing newsprint and photographs.

But scanning and digitization, and storage in a database, are not alone adequate for long-term preservation. True archiving requires forethought and custodianship. To be fair, the tools for the preservation we need are not well developed yet. In the interim, these relationships accomplish specific goals within particular financial realities, but they do not account for the potential impact on long-term preservation and access. While they are expanding to encompass sophisticated access systems under the umbrella of private sector activities, they are also affecting the relationship between user and record on a fundamental level.44 Commercial companies are now the largest stewards of digital news with the potential to affect findability, since standards for metadata and indexing are inconsistent, variable, and based on commercial priorities rather than ubiquitous access.

Platforms

Facebook, Google, and Apple possess considerable news discoverability and delivery power.45 But the boundary between what belongs to the platforms and the news outlets is blurring. In early 2018 Apple News invited the three largest national dailies, The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, and The Washington Post, to contribute to its new digital magazine distribution app, Texture.46 Now the app is home to over 200 magazines.

By and large, media outlets and historical institutions also willingly participated in the Google News newspaper archive, which scanned millions of microfilmed newsprint pages and added them to already digitized content absorbed through acquisitions.47 The project abruptly discontinued service in 2011, however, due to copyright claims by newspaper companies and the complexity of archiving newsprint layouts.48 The content was added to Google News, meaning that another commercial company controls about 2,000 historic newspaper titles, all indexed according to Google’s standards.

In February 2019, Telegraph Media Group switched from Amazon Web Services to the Google Cloud Platform in a deal that expands Google’s reach deeper into the news organization’s publishing infrastructure.49 The Telegraph already distributes digital versions of its news stories using Google Play.50 Soon its digital publishing systems and public-facing digital products will all run on the Google Cloud Platform (GCP). Newsroom staff will be trained to use Google discovery tools to find content and to help develop personalized content for audiences.

Google Cloud also signed a deal with The New York Times near the end of 2018 to turn a collection of about five million printed photographs into digital high-resolution scans.51 Google is providing the Times with an asset management system. Metadata, including information commonly included on the back of a print photo, is assigned and stored in a PostgreSQL database running on Google’s Cloud database. How the metadata is categorized to make the information discoverable is largely based on Google products.

For example, according to Google, the Cloud Natural Language API identifies Penn Station as a location and classifies it (and the entire sentence it was embedded in) into the category “travel” and the subcategory “bus & rail.”52 Media coverage of the deals revolved around increasing productivity and user engagement. Nothing was said of the consequences for relying on a proprietary platform for care and control.

Monetizing the archive

The journalism industry has been monetizing the news (beyond subscriptions) for decades by reselling access to third parties, including commercial information aggregators like NewsBank, ProQuest, and others. These vendors do the work of microfilming and digitizing print, and otherwise making content discoverable. NewsBank, for instance, is a fee-based database of digital articles that acts as a paywall would for content on the live website. In return, the vendors receive a share of what users (including researchers access the content through university libraries) pay for access, and news outlets get a cut as well. Some news outlets license photos of celebrities and sports figures, charging film companies wanting old articles or footage. Local papers, in particular, may attract local historians and genealogists.

Many of the news professionals we interviewed said they saw more of an opportunity for monetizing past content from newspapers than digital-only publications, although noted that how lucrative deals are depend on the terms of the contracts. Beyond money, it’s worth noting that these third-party deals take care of a service that news organizations want (digitalization, microfilming, fee-based information retrieval systems) but see as ancillary to their primary focus, namely publishing news and not preserving it.

Social media

Despite their pervasive use of platforms to publish and promote news content, none of the organizations interviewed said they had practices for saving Twitter, Facebook, and other social media communications. Tweets, Facebook posts, and the like are regarded as “inherently self-preserving” but not of inherent value. This attitude was informed by an acknowledgment that social media is controlled by commercial firms with potentially limited life spans. One data editor said that most reporters take access to platforms for granted until they can’t find something and suddenly realize, “Oh, Twitter might not be forever. It could be gone in five years.”

Tweets, Facebook posts, and the like are regarded as ‘inherently self-preserving’ but not of inherent value.

Despite a recognition that social media posts will have historic worth for future researchers studying the sites, the news workers we interviewed did not consider newsroom posts on the platforms to be news per se. Instead, they perceived news to be fixed on a website or in print, and they regarded social media as a tool they could use to direct audiences to that content. Therefore, they considered saving their social media as unnecessary. “The pointers to the content we don’t worry about,” one person said.

Neither the executive director who said this, nor any other staff we spoke to, initially considered the value of social media for understanding the strategic relationships that have developed between newsrooms and social media platforms. Archival evidence will likely be necessary to examine how these relationships affected reporting and publishing, including headlines, sourcing, or push notifications. Complicating matters, social media companies control access to the content on their platforms. Facebook makes it particularly difficult to crawl its News Feed, even for the account owner. Downloading content from the site when permitted is often the only way to capture it and does nothing for discoverability and long-term access.

Content management systems

Newsrooms rely on content management systems for news production but rarely consider the ramifications of their relationships to them in terms of custody, even though the connection to preservation is critical. It’s an important consideration because the content largely exists in no other location. The majority of newsrooms said they had experienced a loss of content during transfers, which might occur once every three to five years during upgrades, or as the result of a merger or purchase of one news organization by another.

Archivists and newsroom librarians agreed that CMS migrations are one of the most important points of failure. Most news organizations can only estimate the gaps that exist after migration, because the IT departments supervising them run sample searches rather than produce exact file counts. Moreover, they define a certain level of loss as acceptable.

Generally speaking, management systems are not designed for preservation and are vulnerable to server crashes. They are, at best, short-term storage with limited capacity for keeping content in a stable way over time. Worse yet, they struggle to keep track of the various pieces that make up a news story. In this context, several interviewees mentioned ARC, a content management system developed in-house by The Washington Post that brings together the multiple components of an online news story including web print, video, and social media.53 This helps wrangle the moving parts that make preservation different than print. However, ARC is not an archival system. It is useful for production—getting the news published, as one interviewee said—“but what is useful for production is not necessarily the thing that’s useful for history.”

Partnerships

Beyond the platforms, news organizations have experimented with a variety of partnership models that bring print newspapers, public radio and TV outlets, magazines, and web-only producers together in collaboration. Media outlets considered the collaborations necessary in the context of financial constraints attributed to the collapse of print advertising income. One unique form of partnership also involved accepting contributions by non-paid bloggers and special initiatives. A trend that has mostly passed, organizations moved on to new strategies and mostly forgot about these contributions. The blogs have been deleted or neglected.

Furthermore, no long-term plans for keeping the content produced by the other partnerships and initiatives have been established. By way of illustration, Digital First Media founded a project called “Thunderdome” to provide multimedia reporting to a network of local newsrooms.54 Management and former “Thunderdome” journalists said they were unaware of where to find the reporting, noting that it had probably vanished “down the memory hole.”

Shared productivity software

Many of the news organizations interviewed primarily employed Dropbox, Box, and Google Drive to manage content in the pre-publication stages. Each is a cloud-based application that allows users to store and share data online at a relatively low cost without the need for training or in-house troubleshooting. The applications allow multiple users to collaborate regardless of where they are. Story elements can be handed off from a reporter to a copy editor, then a designer, a printer, and an online editor. This flexibility not only makes the system flow but also fits with the nature of dispersed staff and the increased reliance on freelancers. On the flip side, editorial staff members are now very accustomed to using private accounts that ultimately give the user control, meaning the power to delete it and its contents altogether. In the case of Google Docs and Sheets, the user who creates the document controls its accessibility. That removes custody from the newsroom.

These systems also carry with them capacity limitations that can influence decisions about what to keep and what to discard, as well as affect the stability of the system. Those we interviewed from small newsrooms tended to use Dropbox or Box to store image, graphic, and text files. There are several reasons why a newsroom may prefer one over the other, but, either way, news outlets keep content based on the storage capacity they can afford. In addition, they face the possibility of losing content to server crashes or hacks. One newsroom has begun to move staff onto a shared, on-site storage system that centralizes media assets that can easily be backed up at the end of a project. Convincing editorial staff to give up some of the convenience of shared productivity software has not been easy.

Code

Without the computer code in which they are written, the future of newsroom apps is an open question. Much of that code can be found on GitHub and other web-based code management systems, whose popularity is expanding beyond developers to text production. GitHub is loosely equated with an archive in the sense that news developers expect their content to be saved and available in the future. Beyond this, even the largest outfits we spoke to were not archiving their code. However, code management systems cannot provide long-term preservation. In fact, Microsoft acquired Github in June 2018,55 placing the content under private, third-party commercial control. Without access to code repositories, there would be no key to unlock software design and functionality. We might as well be staring at a puzzle without all the pieces.

Comments

By the mid-2000s, online news sites routinely and actively encouraged comments by the public. Visitors to the gender, politics, and culture site Jezebel, for one, prized and encouraged audience comments, a trend that helped shape a culture of commenting that would go on to influence interactions on social media sites. Over time, media outlets began to employ third-party commenting software from Disqus and even Facebook to facilitate this input.56 Outlets, however, began to phase out website comments about a decade ago when they proved susceptible to hijacking by trolls, anonymous contributors, and offensive and inappropriate submissions.57

Interviewees included in this research reported experiencing these problems, and while some shut down their comments, others continued to allow them. Neither group made any provisions for saving comments, though. The sites that opted to shut down their commenting systems could not account for what had happened to their contents. Those who continued to allow comments do not save them.

Microfilming the Internet

In the past, newsrooms, including wire services, preserved the last edition of the day to be published—or, in broadcast terms, aired. But given the atomization and personalization of content and software today, deciding on a final version is anything but straightforward.

One way of thinking about the contrast is the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. The New York Herald printed multiple versions of the April 15, 1865 shooting, some of which can still be found for sale. Today the story might arrive as a breaking news story that would be updated more than a dozen times throughout the day, maybe with video, a photo slideshow, or an interactive timeline written in JavaScript.

As one data editor put it, “I always feel like we’re running our press 24 hours a day every time someone clicks on our site.” Metaphorically speaking, the printing press could break at any moment.

Moving parts

The move online not only required rethinking the nature of content (and producing more of it), but also necessitated changes in staffing. Most media organizations employ IT workers necessary to keep content management systems and websites operational. In addition to these positions, some news organizations invested in specialized divisions of digital news content producers.

Large and medium-sized news organizations produce a variety of data visualizations, tools, and personalized audience applications.58 59 Few organizations we spoke to were actively saving these applications, which are complex in terms of preservation because they are dynamic, atomized, and depend on software that is likely to be outdated in a matter of years.

Subscribers increasingly receive distinct news items personalized to their interests and delivered to them over a variety of devices. It’s difficult to begin imagining how an archival effort would tackle personalization of this kind.

Meanwhile, radio and TV news are also producing news content online and for broadcast. Video and photographs, especially, are often stored on drives maintained not by a newsroom but by individuals. This again introduces the question of ownership and access, all before considering that these materials will always be susceptible to loss if the formats in which they are stored become obsolete and the content cannot be displayed. What’s more, some online sites publish as many as 100 articles a day. “There’s so many pieces,” an editor of a high-volume online site said, “and they’re always moving forward.”

The addition of APIs introduces yet another layer of complexity and external control. APIs enable software programs to communicate with each other via applications that are made up of a series of instructions written in computer code. These applications are common elements in stories, often experienced by users as dynamic interactives that draw on Google location data, tweets, or United States Census Bureau American Community Surveys.60 61 62

Because APIs define how to access that data, when Google, Twitter, or the Census Bureau change instructions, the code no longer works correctly and the application breaks. Developers have no control over these changes, which occur relatively frequently and sometimes without notice.

A similar dynamic occurs with web add-ons that newsrooms adopted but which proved to be short lived. The tool producers were either startups that failed or stopped supporting them. This occurred recently when Google decided to cease its support for Fusion Tables, its map visualization tool.63 Additionally, many newsroom developers noted the current difficulty of playing interactive projects using Adobe Flash software, which Adobe announced it will phase out and ultimately stop distributing by 2020.64 Newsrooms invested heavily in the early 2000s in Flash-based content.65 But now, in the recent words of one editor, “Anything in Flash is dead.”

The pace of software and hardware development is so fast-paced that newsrooms are swapping out both every few years. This leaves little time to think about preservation, which requires advance planning and practices. Instead, media outlets may use up to four systems for handling digital-born news, including both a digital management system such as SCC MediaServer and a content management system, such as Drupal or WordPress.66 67 68 On the web, stories change all the time; they don’t stay static, a newsroom librarian said describing the instability they experienced, adding that, “You can’t microfilm the internet.”

Figure 1: Characteristics of News Publishing, Pre-Internet and Today

Approaches to Preservation

Few newsrooms expressed confidence in their archival practices, or could say that they were taking any steps to make sure that what is published today remains available in, say, 20 years. Rather than a crisis, it may be more useful to think of this as part of a continued transition to a digital infrastructure—one still in flux, with which newsrooms are struggling. While it is true that short-term thinking defines much of the current space, practices for saving content have evolved since the early 1990s. Back then, very few newsrooms were thinking about how to save web files, the result of which meant that news organizations lost early home pages and story posts.

Organizations with the capacity to do so have begun to conceive of in-house systems for saving digital content. The slogan “Lots of Copies Keep Stuff Safe” (known by the acronym, LOCKSS, after the general-purpose digital preservation program of the same name)69 has helped to integrate into newsrooms the idea that keeping multiple copies of stories and story elements distributed via a peer-to-peer architecture, in which no one participant controls all the copies, provides some assurance against server crashes and CMS migrations.

Along these lines, suggested solutions we heard from reporters, data journalists, publishers, editors, and developers were technology-focused endeavors. Although engineering will be an important part of coming to terms with production and preservation, technology is not the only answer or even the best one. Some strategies are further downstream and involve creating policy and preservation standards, for example, around what kind of news content should be preserved and who should have access to it. There is a diffusion of norms that will be required to encourage new thinking about preservation, from the newsroom to the boardroom.

This section considers the benefits and disadvantages of the technology that will underpin digital archiving, and the new models for thinking about digital preservation, from regulation to workflow, that it will force us to confront.

Upstream

Blockchain

Blockchain startups have marketed the software as an archival solution based on the premise that copies of digital files distributed and stored on multiple servers can prevent against deletion and undetected changes to data. One such startups is Civil,70 which caters directly to the journalism industry, using Gawker as a cautionary tale. But marketing strategies do not translate into long-term preservation practices. While blockchain software stores information about articles, it is not well equipped to store actual articles, photos, videos, or other data.

The InterPlanetary File System (IPFS), a peer-to-peer, distributed network protocol that pairs well with blockchain, seeks to overcome the storage limitations of blockchain applications by adding actual files rather than limited metadata to the datastore.71 This does, however, slow operations and increase storage costs. Still, marketing efforts around blockchain technologies have opened the door to a discussion about the need to have strategies for keeping digital content accessible.

DWeb

An alternative decentralized network, referred to as the decentralized web or DWeb, is being developed in response to perceived weaknesses of the current internet structure, including central control and capture of data by Google, Facebook, and other platforms.72 In the decentralized scenario, software breaks files into smaller bits. They are then encrypted, distributed, and stored on a network of laptops, desktop computers, and smartphones.

The plan capitalizes on unused storage capacity on users’ computers. At this point, enlisting smartphones in the plan is more aspiration than reality, although supporters see the gap narrowing with the availability of 5G wireless networks. Moreover, the DWeb rationale rests on surveillance, censorship, and control. Archiving is conceived of as the storage of bits of data broken into pieces and dispersed across multiple computers. While redundancy does protect against deletion and helps to identify that a change has been made (albeit not the actual change), decentralization as imagined by its supporters does not easily reconcile with long-term institutional models for preservation unless the system can be adapted to their controls. For example, the Library of Congress could develop its own decentralized system that would be able to track the location of bits of information.

Better links

In the world of the web, article links are not robust.73 Broken links that return a 404 error message can damage the credibility of news organizations, and some have invested considerable staff time to confront the problem. Several strategies can help make sure that content, including versions, remain available over time. The Associated Press Style Guide recommends including in a URL (uniform resource locator) the same elements, in the same order, as would be done for a reference to a fixed-media source.74

Permalinks and digital object identifiers (DOI) offer options for providing more stability. DOIs are part of a system relatively common among scientific and academic publishing in which a registration agency (the International DOI Foundation) assigns an object (i.e., an article) a unique alphanumeric identifier to content.75 If a URL changes, the DOI can be redirected to continue to identify and locate the article or other digital object.

Ally archivists

In the meantime, collectives are filling the gap by saving digital objects that would otherwise slip through the cracks and become obsolescent before their value can be recognized. For example, NewsGrabber, developed by Archive Team (“a loose collective of rogue archivists, programmers, writers, and loudmouths dedicated to saving our digital heritage”)76 seeks to enhance the Internet Archive’s efforts to preserve news content.77 A member of Archive Team also launched an effort to preserve and manage as many Flash games as possible before they’re no longer playable.

These initiatives are not all specific to journalism—and they can be a bit tech-heavy—but the resources offered by these groups can be relevant to saving digital news products, especially interactives. This will likely not only include Flash-based games, but the new applications being built today, such as ProPublica’s “Dollars for Docs,”78 whose formats will one day be obsolete.

Emulation

Consisting of multiple parts, games and interactive news applications (usually custom-made) pose a particularly vexing challenge to preservation that migration and distributed copies fail to fully address. To preserve not only the content, but also the purpose and functionality of dynamic, interactive applications, Katherine Boss, librarian for journalism, media, culture, and communication at New York University, and Meredith Broussard, assistant professor at the Arthur L. Carter Journalism Institute of New York University, are developing the first emulation-based web archiving tool. The package would save the entirety of a news app while also providing a digital repository to preserve it for future use, thereby facilitating the look and feel of the original interactive experience.

While other emulation projects are being developed—at Rhizome, the Internet Archive, Carnegie Mellon, Yale, Deutsche Nationalbibliothek, and the British Library, among others—what distinguishes Broussard and Boss is not only an institutional infrastructure that takes into account long-term preservation and access by integrating librarians into the system; their project also formally addresses emulation-based web archiving.

Workflows

Data journalists and developers told us that news preservation starts with changing attitudes, but also emphasized that incorporating strategies into workflows would be necessary for success.

My feeling is if you can’t have the archiving built into the production workflow, then it’s not going to happen because people are going to move onto the next thing . . . As soon as their things are published, they don’t care anymore. So unless you can get them to do it on the front end, it’s always going to be killed.

With developer workflows in mind, Ben Welsh, data editor at the Los Angeles Times, has developed the PastPages software toolbox to assist in saving digital-born news by making content easy to save—or, as he calls it, “archive ready.”79 By way of example, the plugin Memento for WordPress can send preservation requests to third-party institutions like the Internet Archive upon publishing each time content is modified.80

Another application, Save My News, helps individuals save URLs in triplicate distributed across multiple servers.81 Welsh describes it as a personalized clipping service that empowers journalists to preserve their work in multiple internet archives. These can be integrated into a web browser, similar to the reference management software Zotero: users click on an icon located in the upper corner of the web browser to save content.82

Welsh also recommends configuring web pages and software so they’re easier to archive. HTML headers can include a message that permits third-party organizations to collect the web page or site. Software can be designed modularly to integrate easily with “snap on tools” like Memento for WordPress and content management systems. In this way, organizations like the Internet Archive becomes a sort of platform that allows users to curate collections and store them on third-party servers.

PastPages has won an innovation award from the Library of Congress and praise from the Nieman Journalism Lab, The Wall Street Journal, Journalism.co.uk, the Poynter Institute, and other organizations.83 But uptake faces obstacles within news organizations. The software is open source, lacking the institutional support necessary for the kind of development requisite for long-term integration in news organizations. Also, newsroom managers may have reservations about using non-enterprise software. When we asked if this points to the need for an infrastructure involving government support and regulation, a newsroom developer said, “We need some institutions to step up—if they can.”

Downstream

Regulation

The centerpiece of US regulations for mandatory deposit of news content revolves around print newspapers, and is administered by the the US Copyright Office and the Library of Congress. But no mandatory deposit regulation exists as of 2019 for digital news content made available on the internet, although initiatives and rule-making discussions regarding digital-born news continue (see the Appendix of this report for more).

The United States is not alone in its absence of mandatory deposit regulations, but it may be unique in the considerations that will be involved: mainly the scale at which news is produced in the United States, as well as the rate of change in news layouts and content that challenged even a well-funded, technologically equipped project like Google News Archive. The result is a patchwork of participants in the commercial, nonprofit, government, and public sectors with a variety of needs and capacities.

Even if legislation did exist, the Library of Congress alone is not yet equipped for the volume, complexity, cost, and technical challenges that digital-born content presents for meaningful preservation.

They vary by region and some states are working with their local press associations, while the Library of Congress has hosted multiple stakeholder meetings with news organizations to discuss the preservation of digital news. Even if legislation did exist, the Library of Congress alone is not yet equipped for the volume, complexity, cost, and technical challenges that digital-born content presents for meaningful preservation.

Integrate news production teams