Last June, Report for America (RFA) fellow Will Wright was looking for interviews in Eastern Kentucky. He was standing at a temporary health care clinic where hundreds of people were lining up to receive free medical and dental services offered by the United States Army. He decided to try three men he saw waiting. “I was like, ‘Hey, I’m writing a story for the Herald-Leader,’” Wright told us.

Wright’s RFA fellowship had placed him as a reporter for the Lexington Herald-Leader, where he had interned as a student at the University of Kentucky. But the fellowship put Wright some 140 miles east of Lexington, just outside the town of Pikeville. From here, he was tasked with reopening the Herald-Leader’s Southeastern Kentucky bureau, covering some 13 Appalachian counties.

As Wright was reminded while out doing interviews, he did not enter this region with a clean slate. For some, like the three men he approached at the Army clinic, the Herald-Leader’s reputation preceded him. “They were like, ‘Oh, no. We don’t really want to talk to you,’” he recalled. “I was like, ‘Why?’ …They just said straight up, ‘We don’t trust the Herald-Leader.’”

Wright’s encounter illustrates the current of distrust against which many Report for America fellows can find themselves swimming—after all, the top criteria for newsroom selection, according to Report For America’s site, is that it is aimed at an “urgent need” where “topics, communities, or geographic areas” have been “under-covered.” In Wright’s case, he realized that many people he spoke with saw his news outlet as “‘the liberal Lexington paper, you know, who doesn’t understand Appalachia and who hates the coal industry.’”[1]

Some 500 miles away in Chicago’s West Side neighborhood of Austin, Report for America fellows had to grapple with representing the Chicago Sun-Times, an outlet known in that community primarily for its crime coverage, which many of the residents we spoke with saw as skewed in favor of the police.

Entering communities where mutually beneficial relationships between residents and news outlets may have collapsed—or were never established—where can Report for America fellows begin? Can they build trust? And how do they balance their mission to offer coverage for the communities they are covering with the structural necessity to appeal to the broader audiences of their outlets?

This study looks at a local news capacity-building initiative in two communities where residents have long complained of stigmatizing news coverage: Pike County, in Eastern Kentucky,[2] and Chicago’s Austin neighborhood.[3] That initiative is Report for America, a project that seeks to place 1,000 reporters in local newsrooms by 2022 by paying half the reporter’s salary.

But this study looks at those efforts within the larger communication context of each community. We examine how residents assess outlets that cover their area, focusing on perceptions of three components or factors[4] of trust: accuracy and credibility, respectful and equitable representations, and benevolence of the journalist’s or outlet’s motives. These factors are subjective by nature—they describe community members’ perceptions of their own experience of interacting with the media, both as subjects and as readers. We then examine the RFA interventions in both locations—how journalists pursue ambitious goals with limited resources, what residents make of these efforts, and what residents believe would further strengthen relationships between communities and local news. We end with some recommendations for the next phases of Report for America, as well as others seeking to strengthen the capacity of local news.

Our study sites and methods

Launched in 2017, RFA is a massive project, operated in partnership with some 50 news outlets across 28 states and Puerto Rico. In addition to its start-up funds from Google News Lab and others, it recently received a $5 million cash infusion from the Knight Foundation. Last week, RFA also announced the placement of 61 fellows for their 2019 cohort (positions for which they received 940 applications). This, then, is a moment of expansion for the project, and a good time to examine a couple of the communities selected by RFA for its initial work.

One of RFA’s first fellows, the Lexington Herald-Leader’s Will Wright, now covers Southeastern Kentucky from a “bureau” based in his trailer in Pike County, about two and a half hours from Lexington. The McClatchy-owned Lexington Herald-Leader is the second-largest newspaper in Kentucky, based out of Kentucky’s second-largest city. Our study focuses on Pike County. It is the largest of Kentucky’s 120 counties, spread across 789 square miles, but is only one of 13 counties in Wright’s vast coverage area. Compared to surrounding counties, the estimated 58,883 residents of Pike County, 98% of whom identify as white, have some benefits from the strong economy in the county seat of Pikeville—a regional hub with a university, medical campus, and other businesses that draw residents of surrounding counties. But the county’s median household income still trails state averages—just under $33,000, compared with the state average of nearly $47,000—and nearly 30% of residents are estimated to be below the federal poverty line. This part of Eastern Kentucky, which has a long history of coal mining, is no stranger to unflattering media depictions,from coverage of “Mountain Dew mouth” to JD Vance’s bestselling but controversial memoir, Hillbilly Elegy.[5]

Our second research site is one of the neighborhoods within the coverage area of two RFA fellows reporting for the Chicago Sun-Times, Carlos Ballesteros and Manny Ramos. The pair joined the Sun-Times with the ambitious mandate of covering the city’s majority Black and Latinx South and West Side communities—which, as Ramos explained in an interview, are essentially “two-thirds of the city.” Our study focuses on the Austin neighborhood on the city’s western edge. The second largest community area in Chicago, Austin is home to an estimated 99,711 people, 84% of whom identify as African American and 10% as Latinx. With a median household income of just over $31,000 (compared with the city’s average of nearly $48,000), Austin continues to suffer the consequences of Chicago’s historically racist housing policies, residential and institutional segregation, and economic disinvestment in its Black communities. Likewise, residents of West and South Side neighborhoods are more likely to feel misrepresented by news media than residents of Chicago’s majority-white North Side.

To understand how residents in these two communities felt about local news, trust, and the RFA program, we checked in with 28 residents over the course of six months. In July and August 2018, we held two focus groups in each location, discussing perspectives on local news, using examples from before RFA’s intervention. For half of the people in these groups, we followed up monthly by email with stories from news outlets covering their community (including the Herald-Leader and the Sun-Times). For the other half, we did not, so that we would be able to assess whether residents were finding this material on their own, and whether exposure to materials produced by RFA would affect participants’ attitudes regarding local media.

Then, in February 2019, we followed up with all the groups to discuss any changes in their news habits, their associations with the newspapers housing RFA fellows, their assessment of local news story samples, their notions of what local news should be, and their ideal relationships with journalists. To get the perspective of journalists, we also interviewed 15 reporters and editors from outlets active in these two communities, including journalists affiliated with the RFA project.

Finally, we logged three randomly constructed weeks of coverage coming out of the Herald-Leader and Sun-Times before and after the RFA intervention. We noted the articles’ length, theme, and key points to chart the broader themes being covered about Austin and Pike County.

Summary of key findings: Moving the trust needle

Increasing public trust in news outlets is a tall order, particularly for larger media organizations that have spent years unable to address their reputations for covering communities of readers only when bad things happen to them—or, worse, not covering them at all. The cases of Pike County and the Austin neighborhood of Chicago illustrate what residents mean by “trust”—a messy conglomerate of interrelated factors of accuracy and credibility, representation, and perceptions of the motives of news outlets. Each case demonstrates why anyone attempting an intervention in a local news ecosystem must be mindful of place and power dynamics.

- In Pike County, for example, residents pointed to a history of outsiders—not just “coastal elites” but people coming from other parts of their own state—trying to take advantage of their community. Because of this, participants were finely attuned to notice a range of triggering practices, from overt, clearly exploitative parachute journalism to subtle ways a well-intentioned outsider would emphasize story elements that a local resident would not. In Chicago’s Austin neighborhood, a history of racist misuse of authority left many residents doubting the motives of journalists, particularly when they were seen to include authorities in reporting that left out community members. Participants were critical of news coverage that perpetuated stereotypes connecting their community to crime and crisis.

- In both places, participants expressed a wariness of journalists’ motives, concern that they might deliberately represent the area to conform to stereotypes, and a sensitivity to details that could signal that a story was intended for an external audience.

- Residents in rural Kentucky and inner-city Chicago shared a sense that RFA fellows’ stories were more about their communities than for them, but participants acknowledged that circulating more complete narratives about their communities was not a small thing. While RFA Co-founder Steve Waldman stressed that RFA’s goal was to help communities get better coverage for themselves, RFA came into being at a moment following the 2016 US elections when journalists felt keenly that the outcome of the election would have surprised them less if only they had understood these communities better.

- Given this need, it is natural that RFA would dispatch fellows to report on communities that have been stereotyped or overlooked for large regional outlets. In communities where these outlets rarely sent reporters, or where residents felt that all coverage had been negative, publishing stories at variance with the stereotypes those residents dislike and resent can be a meaningful contribution. Participants suggested that, even if stories weren’t written specifically for them, circulating more nuanced stories about their communities could have a material impact, making it more likely that outsiders might visit or invest.

- We believe RFA interventions in Austin and Pike County offered the potential to contribute to more trusting relationships between news media and local residents. RFA fellows were motivated to share community stories, and to try and represent communities respectfully and accurately. But in Pike County and Austin, these efforts were limited. Because typical reporting focuses on one-way relationships with residents, in which regional outlets connect with them merely as sources for stories intended for their broader readership, or as readers among that broader readership, the ways that community members can see to be involved in the process of journalism are limited. In our focus groups, residents envisioned a variety of additional pathways through which they could be involved in the reporting process. And the structure of the fellowships—where reporters were tasked with covering vast areas, and required to conduct service projects but not community outreach—made it especially difficult to establish deliberate feedback loops that would have served both journalists and the residents in our focus groups. When we told residents about RFA, they responded favorably. But, at least in these early cases, RFA fellows and outlets have not been able to prioritize deep relationships with communities they cover.

In the pages that follow, we share more of our findings, and offer recommendations for ways forward.

Newspaper vending machines for the Lexington Herald-Leader and the Appalachian News-Express side by side

Eastern Kentucky bashing

“If you’re watching MTV, would you rather see them make their own hot tub out of the back of a pickup truck, or would you rather see them do the zip line here in Pikeville?” a participant in one of our focus group discussions asked.[6] In our discussions in Pikeville about media produced prior to Report for America’s intervention, several residents mentioned Made in Kentucky, an MTV reality show filmed in Pike County’s Elkhorn City, as an example of the media’s stereotypical representations of the region. One participant had briefly done work for the show. He found the process revealing: “I asked them, I said, ‘How did you find these people?’ They said they just came into restaurants until they found the rowdiest place and the rowdiest people they could find.”[7]

While most participants did not have first-hand encounters with media makers or journalists, no one seemed surprised by this explanation for how media sought out people to represent the area. Residents recognized that reality television is not the same as news media but considered it context for how outsiders represented their region in general. As another participant said, “Every time I turned around, somebody was bashing Eastern Kentucky with some kind of ill-informed documentary.”[8]

If we break “trust” down into three factors—perceived accuracy, quality of representation, and benevolence of motives—media outlets covering Pike County did not fare well in residents’ eyes. Focus group participants critiqued news stories for leaving out historical context or providing the wrong type of detail—they objected, for instance, to providing lurid details in crime coverage but not context about the broader societal problems that may have contributed to the crime, or resources dedicated to solving it. Participants also objected to what they saw as disproportionately negative coverage. They asked why news outlets didn’t talk about the contributions of the local optometry college, or local tourism initiatives.

When assessing the motives for this coverage, residents speculated that news outlets leaned toward sensationalism and negativity to make a profit. Many talked about the regions from which the journalists reporting and editing the stories came. As one participant, Matt, explained, “If it’s anything written about Eastern Kentucky [that] doesn’t originate in Eastern Kentucky, I’m probably not going to believe it.”[9] Several referenced the Lexington Herald-Leader in the context of coverage by outsiders, suggesting the paper tended to cover Eastern Kentucky unfairly, if at all.

At the same time, local news produced in Pikeville, like the thrice-weekly Appalachian News Express newspaper, also had its critics in the focus group. While several participants noted favorably that the News Express did include coverage of positive developments in the area, like new businesses or youth sports, others lamented that it still ran too many negative stories, especially those highlighting arrests and drug use. As one participant put it,

I would love for there not to be three and four articles every time the News Express is published about the lady wandering in the middle of U.S. 23 blown out of her mind on methamphetamines …I would just like for them to look for the good as much as they look for the bad.[10]

Others suggested the News Express and other outlets didn’t do enough investigative reporting. They saw coverage gaps around local governance, and the positions of candidates in local elections. One participant asked, “What are these people who’re going to be running this county actually thinking? What are their actual ideas?” Another agreed, complaining that they never heard about candidates’ plans and then got unwelcome surprises like 30-to-40% property tax increases.[11]

When the group considered stories produced about their communities before Report for America’s arrival, there was a sense of dissatisfaction among participants, both with the community’s portrayal by outsiders, and also with the availability of in-depth community news and information within Pike County.

Mr. Wright goes to Pikeville

When Will Wright arrived at his Southeastern Kentucky post in January 2018, John Stamper, his editor at the Lexington Herald-Leader, admitted he had some concerns. “Plopping a 22, 23-year-old down in Pikeville and saying, ‘Go to it!’” Stamper said. “I mean, that’s, there’s a big learning curve there.”[12] But Wright hit the ground running. Within weeks, he reported a major story about the residents of Martin County going days without running water due to a combination of freezing temperatures, years of slipshod management, and neglected infrastructure. His reporting prompted action at the county and state levels, and RFA used this impact as proof of their case for reporting on the ground in areas where there had been no locally based reporters.[13]

Since that first series of stories, Wright has gone on to file about four stories a week on a range of topics, including water and environmental issues, economic development efforts, and the local schools. Wright has 13 counties to cover, but many of his stories were about Pike County, where he is based.

We held our first set of local focus groups in Pike County in Summer 2018. Then, a year into Wright’s fellowship, we returned to check in with the same groups of local residents. For six months, we had been sending one of the groups monthly emails with links to stories from both the Herald-Leader and the News Express. We had not communicated with the other group. When we invited participants to share further reflections on both outlets, there was no significant difference between the two groups’ reactions. Most participants said they appreciated that they could go to the News Express for local stories and possibly see their child in the paper. But several complained the News Express tended to be opinionated, and few were willing to subscribe to get past the paper’s online paywall.

Regarding the Herald-Leader, most participants expressed some variation of the following sentiment, similar to the attitude of the men Wright met at the health clinic:

I think they’re biased. They’re untrustworthy, and they don’t care about East Kentucky. All they want is the sensationalism of news. This is my humble opinion, and I believe that they have a tendency to down the area and try to make us seem like the hicks that everybody thinks that we are, anyway.[14]

One participant in the group to whom we had been emailing stories said she had bought a digital subscription for the Herald-Leader since we last met. She said that, mostly, she appreciated the paper’s statewide news. “I think the articles are more in depth,” she said. “While there is negative press, I’m not sure it’s negative because it’s not true.”[15] A few other participants said they liked the Herald-Leader for its state and national news, and its University of Kentucky basketball coverage—though some of these residents also noted that the paper was much thinner and had less news than in the past. “You’d pull it out of the machine, and you’re like, ‘Wait, somebody has taken the inside!’” said one. “No. That was all.”[16]

But “Is he a local boy?”

Wright said that, when he met skeptics of the Herald-Leader as he was reporting, he would sometimes tell them, “Maybe after this story, you’ll change your mind.” But the skeptical participants we met either were not reading these stories, or, if they had read them, didn’t know they were written by someone based in the area. None of our focus group participants had heard of Report for America or Wright.

Wright attributed this to the fact that the credit for RFA is positioned at the bottom of the story. “I don’t think people will read that. I mean, they barely read the byline,” he said. The Herald-Leader’s Pike County bureau also was effectively invisible. Wright had opted to take a stipend for working out of his trailer rather than renting an office. A year in, Wright admitted to having second thoughts about the decision.“It would be really valuable to have an office with a sign to show people when they’re driving through town that’s like, ‘Hey, we’re here!’” he conceded.

When we told our study participants about Wright, both groups asked the same question: “Is he a local boy?” In one group, there was considerable speculation about Wright being a local name and participants tried to figure out if he might be related to anyone local. As one said, “We are clannish.” But they all agreed there were legitimate reasons for the question:

Bob: Really and truly, when you think about it, that goes way back, because outside people come in, and didn’t do the ethical thing.

Randy: Take advantage of us.

Allison: Yeah.

Bob: People coming in, but if they’ve got roots here, you feel more comfortable with them.

Randy: Because they know the values and whether there’s a foundation there for them.

The skepticism is warranted. As recently as March, the News-Express ran an open letter from its editor to CBS’s 60 Minutes, condemning what he called the show’s shoddy reporting about the area in a segment following Hillbilly Elegy author and venture capitalist JD Vance around the country with billionaire Steve Case; Pikeville was one of the story’s stops. 60 Minutes has not corrected any of the mistakes he mentions.

In the other group, Bruce cut to the chase: “Where is he from? I mean, what I’m asking is basically, ‘Does he have ties to Eastern Kentucky? Is he going to be biased against us or what?’”

Wright, who is originally from southwestern Pennsylvania, was aware of the sensitivities Eastern Kentucky residents had about outside reporters:

I think people here are probably especially sensitive to reporters from the outside coming in and telling their story for them…A lot of those outside reporters who come in, it’s like they’ll come here and see, write a story about, like, “This is my value; how do these people feel about it?” rather than being, like, “Hey, what do you care about what matters to you?”

Wright said he tried to account for this by listening to people, treating them with respect, “having a sense of the history of the place, and knowing about how extractive industries have helped and hurt the economy.”

When RFA was first announced, many raised concerns that it would perpetuate parachute journalism.[17] Rather than hiring reporters who already lived in an area, the project would send outsiders in to marginalized communities for limited periods of time. Kevin Grant, the vice president of RFA, said that the program was open both to journalists who were from communities they covered and journalists who were not: “As long as the journalists have the proper time to deepen relationships with their communities, they don’t have to be from the place,”[18] Grant said. Grant also said that, during their training, RFA fellows were suggested strategies for developing connections with local residents:

Maybe you become a bit of a fan of the local sports team, or maybe you make a bit of a show of the fact that, if you’re working in a rural area, that you are into hunting or fishing, if that’s true—just other ways to make yourself more relatable and accessible as a journalist in parts of the country where people can be really skeptical of journalists.

Wright did hunt and fish, and he must have internalized this advice, as he mentioned how he’d talk about those hobbies to establish common ground. But is a one- to two-year contract long enough to deepen these necessary relationships? A year in, Wright said it would probably take about five years to have really deep contacts, and that it had already taken him eight months to gather a “solid small network of people I could call and have their cellphone numbers.” He said that, even after that first year, “I’ll still meet people that I should know and should know me, and they’re like, ‘Oh, you live in Lexington,’ you know?”

Wright was given a second one-year contract, so he had some time after that first eight months of relationship-building. He seemed doubtful that he would be able to stay in the area past the two-year mark, though he said he hoped the Herald-Leader would continue to cover the region.

In terms of building relationships with communities, Wright’s only structured opportunity for community engagement outside his newsgathering duties was the service project RFA required him to perform. He worked with a class of students, helping them edit narrative essays about working to overcome stereotypes. RFA did not require Wright to crowdsource story ideas, convene pop-up or public newsrooms, or otherwise create “feedback loops” of communication with residents. The program has included training modules that emphasize social journalism, and RFA suggested they might consider additional training or other ways to incentivize community engagement in the future.

But, if Wright’s experience is typical, it seems unlikely that RFA reporters will be able to undertake this work, unless it is built into the project design. “I just think of myself as a reporter first and foremost—that’s why I came here,” Wright said. He explained that, while he thought community engagement work sounded valuable, he didn’t really think of it as part of reporting. He already struggled to find time for RFA requirements like his service project or mandatory essays about his RFA experience. And, a year in, there were still counties in his coverage area where he had not spent significant time and in which he had not yet built a strong network of contacts.

Focus group participants in Pike County, however, had a number of ideas for new modes of communication that could improve relationships between journalists and residents like themselves. These ranged from town meetings about civic issues, to journalism literacy classes, to open office hours, to simply visiting senior citizen centers. Participants also suggested that reporters create opportunities to crowdsource story ideas via text messages, and take polls via social media. One group suggested a weekly feature highlighting which local resources were available and to whom, covering everything from going back to school to post-prison reentry, by collaborating with people involved in various community organizations and initiatives.

Balancing local and state-wide audiences

One primary question remains, both for RFA and for other projects like it: How can newsrooms both meet the information needs of communities they cover, and simultaneously appeal to the outlet’s general audience? As Herald-Leader editor John Stamper put it, “The audience does need to be broader than just one particular community. How does this impact the region?”

Wright said there were occasionally stories he had to drop because they were too hyperlocal. “We’re not the daily paper in Pikeville,” Stamper said. Both men agreed they were not trying to compete with the Appalachian News Express. But, for the stories that met the Herald-Leader’s threshold, Wright said he still works to consider both local and statewide audiences. “I try to write the stories in a way that makes sense for both and, like, matter to both,” he said.

In our discussion groups, we gave participants a Herald-Leader story by Wright and a story by a reporter at the News Express without providing their bylines or the names of the outlet. Wright’s piece was about a major effort to clean up trash at an area lake. Several participants, including Ray, expressed surprise that the Herald-Leader “ would actually care about what’s going on at an East Kentucky lake” when we told them which paper had printed each story. He was impressed that the story didn’t say “anything derogatory about Eastern Kentucky.”[19]

In the other group, however, two participants argued that it actually wasn’t surprising because Wright’s story was negative “It’s still talking about our horrible pollution problem here in Eastern Kentucky,” one said.[20] The other participant, Bart, said he saw stylistic difference between Wright’s piece and a News Express story about a recent fiscal court meeting that the group also read. Bart suggested the Herald-Leader piece was more well-written, but that it seemed to come from an “outside perspective.” “It would be a little bit different if it was written by someone who lives here,” he said. “Like when I read this, it doesn’t feel as personal.”[21] Others noted that the story focused on details that might concern outsiders who visit as tourists and would be troubled by the aesthetics of the trash, rather than locals, who were more concerned about the trash’s potential to cause flooding.[22]

When RFA first planned to come to the region, it considered partnering with the News Express to help to ensure strong ties with the community, and act as a kind of exchange program with the Herald-Leader. RFA officials explored having Wright work out of the News Express office and share his stories with the Herald-Leader. Jeff Vanderbeck, the publisher of the News Express, says he told RFA, “If you want to talk about the good things, and you want to dig deep enough and get the true story, I’m all about it.” He was not happy about RFA working with the Herald-Leader:

I said, “Here’s my concern. Every time the Lexington Herald-Leader writes and editorial about Eastern Kentucky, it’s bullshit.” I said, “I’m tired of dealing with these guys.”…They write crap about this region, and they lie about it.

For Vanderbeck, the News Express was part of the community, playing a critical role in holding local authorities to account, but also highlighting positive local developments. Perhaps because of this tension with the Herald-Leader’s perceived attitude about the area, there has been little progress toward collaboration since Wright arrived. Wright did note, however, that he has made efforts to link to News Express stories in his writing after talking with representatives of the outlet about the perception that outside stories often used the paper’s reporting without proper attribution.

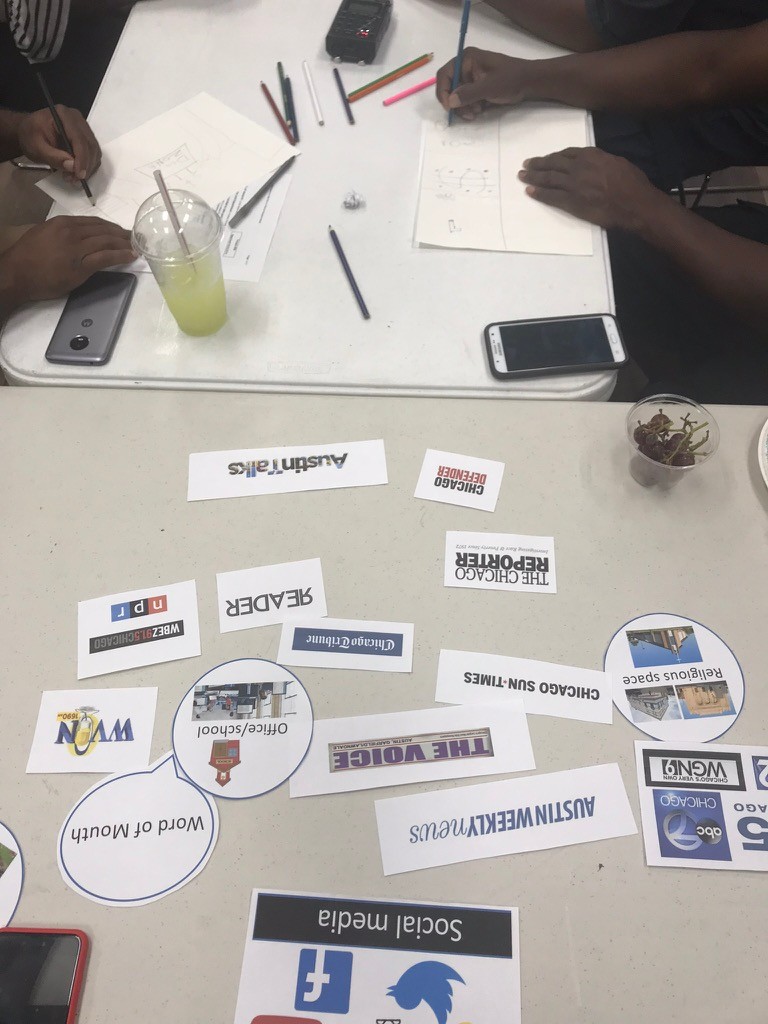

Focus group participants discuss their local communication ecologies

Black Chicagoans ask, The news according to whom?

“I found a lot wrong with this story,” Austin resident Kianna said, responding to a 200-word article in the Chicago Sun-Times about the police shooting of a man in the Austin neighborhood of Chicago’s West Side. “They heard gunshots, gunfire near this address. This young man [the victim] was sitting on his porch minding his own business.”[23] Most participants in our focus groups agreed that there were many gaps in the Sun-Times story. “The story jumps right into, ‘The officers found the man on a porch, and then he ran from them.’ Who knows what the officers did to provoke that?”[24] Another participant, Amber, argued that if the newspaper wanted to run a story like the brief shooting write-up, its editors should make room for more details. Otherwise, readers were left to make assumptions based on “what you’ve already represented us to be”—“you” being the mainstream media, “us” being Black residents of the neighborhood.

The brief may have seemed to be a straightforward accounting of relevant facts to the Sun-Times editors who signed off on it. But, for residents of a community historically stigmatized in media portrayals and mistreated by a police force accused of abuses of power, the set of facts seemed to rely too heavily on the perspective of the police, as another resident, Ayesha, pointed out:

I found myself counting how many times, ‘the police said, police said, police said, police said’ or ‘officers,’ or, you know. So this is Austin according to the police. And, more often than not, the police, they don’t live here. So it’s not really reflective of the community at all. I mean, it’s just about this instance that happened in Austin. And it’s as if there were no one else there but police and the people who they were engaged with.[25]

In our focus groups, Austin residents’ reactions to crime coverage illustrate how such coverage can undermine key factors of trust—how people perceive a news outlet’s accuracy, fairness of representation, and motives. First, participants spoke not only of stories seeming incomplete, but also being inaccurate. Lee complained that television outlets were so eager to be the first to break a story that they didn’t devote adequate time to verifying details: “A young man’s life was taken. He was three different ages. He was 27, 32, and 42 if you listened to three different news.”[26] Participants also complained that local news did not represent Austin fairly, as reporters “always get the worst person to represent the community,”[27] like “Pops on the street that … you know, had a few drinks or missing a few teeth.”[28]

Finally, even more than in Pike County, participants were skeptical of the motives of news outlets. Several suggested news media had intentionally omitted information, such as details that could have cast an unfavorable light on the police. Some also suggested that journalists attempted to manipulate their audiences. A few attributed these transgressions to racism toward the Black community. “The news and the media, for whatever reason, does not want to shine the light on us, you know,” said one participant, Gloria. “[It’s] racism, [or] whatever you want to call it. At the end of the day, they don’t want to shine the light on us, and this is just another way of doing it.”[29] Others believed that reporters were being directed by their outlets or editors to skew coverage in a negative direction. Often, this was connected with an assumption that sensational negativity sells:

You know, I think that the journalists write good stories. I think the editors don’t always allow the story to get out because…if you’re in the system that says, ‘This is what we want to see;’ ‘This is what’s selling’ ‘This is what’s grabbing attention,’ then you could have good stories but those get pushed back to the last two minutes of the newscast, right?[30]

Beyond crime coverage

RFA fellow Manny Ramos did not deny that negative crime coverage sells. “Crime reporting is very important to the papers, right? Like, it drives in revenue, a lot of page views,”[31] Ramos said. But, he added, the problem came when crime stories were the only coverage a community received. He recalled that being the case when he grew up on the West Side, on the border with Austin. As an RFA fellow, Ramos and his colleague Carlos Ballesteros have been assigned to write more nuanced coverage of the city’s majority Black and Latinx South and West Sides.

The pair are rarely, if ever, assigned to breaking crime stories. “We can’t just send them to the crime scene,” Chris Fusco, the Sun-Times Editor-in-Chief said.[32] Because of their agreement with RFA, the two fellows covered a range of community issues—economic development, immigration, educational initiatives, health disparities, demographic trends—anything but crime. Because the Sun-Times had gone through layoffs and ownership changes,[33] reporting manpower was stretched thin. “There’s days, believe me, you would love to take the warm body that’s in the newsroom and dispatch it to whatever crisis that is going on,” Fusco admitted. “But we can’t do that.”

This is not to say that Ballesteros and Ramos don’t occasionally get sucked into second-day crime stories. When that happens, Ramos said he tries to humanize the community and the people involved: “It’s still not ideal for me. I would rather not cover that at all. But at least I’m doing something that is not just taking the account of the police.”[34]

The difficulty with their mandate was the size of the task, as both reporters pointed out. “It’s a massive beat to cover,” Ramos said.[35] Ballesteros said it could be difficult to prioritize given the scope: “I’m glad it’s my job, but it is kind of gargantuan,” he said. “I wish we had a whole team.”[36] Just as in Eastern Kentucky, because of the size of their coverage area, the work the RFA fellows produced could feel like a drop in the ocean.

Comparing three randomly constructed weeks prior to the beginning of their fellowship with three randomly constructed weeks six months in, we found fewer stories directly referencing the Austin neighborhood (from 44 stories down to only 10). These numbers may be explained in part by the times of year we compared. It was spring heading into summer (April-May) at time one, but time two was during winter (in Chicago crime tends to spike with warmer weather). But noticeably, crime coverage was dominant at both times—40 of the 44 stories before the RFA intervention were about crime, as were 10 of the 10 stories from six months after (none of those 10 stories were written by the RFA fellows). So for Sun-Times readers, the odds of coming across crime coverage about Austin were higher than happening across a feature by RFA fellows.

Missed connections

Each time we met Austin residents—first as the RFA program was beginning, and again about six months later—we asked how residents saw local news outlets, paying particular attention to the Chicago Sun-Times and the neighborhood’s community paper, the Austin Weekly. When we first talked to residents, several articulated a variation on Keisha’s perspective: The Sun-Times and its rival the Chicago Tribune both seemed “cold.” “It doesn’t seem like it’s for the minority group. It’s like the, maybe more elite or upper class,” she said. “ …‘I’m on my way to work. I want my news really quick.’”[37] Keisha contrasted the rushed quality of the major papers’ writing with the writing in the Weekly, which she considered “warm,” “because it has a stake in the community, so it cares about what the community is doing.” These views did not seem to shift six months in. Most participants considered the Sun-Times a source for city-wide news, and remained concerned about negativity and coverage that favored the viewpoints of police or politicians.

Despite this, when we shared a Sun-Times article Ramos wrote about a community initiative in Austin in focus groups, without identifying the outlet or byline, participants responded favorably. One participant, Lee, said the article “let you know that, if you lived in Austin, that there is someone working to help revitalize Austin.” He appreciated that the article “informed me of where I can go to get some more information if I wanted to see my community look better.”[38] Some participants deliberated about which outlet the article came from. Some thought its positive focus on the community meant it likely came from the Austin Weekly, though Lee guessed it was from a city-wide outlet: “Because what they normally talk about is the murders over here in Austin, every now and then, they’ll do a story that says, ‘Hey, this is what else is happening.’”

As in Pike County, none of the participants had heard of Report for America, or Ballesteros or Ramos. And, as with the RFA fellow at the Lexington Herald-Leader, community engagement and outreach efforts in Chicago had been limited. Ballesteros co-hosted a bilingual candidate forum in the electoral ward where he lived, and planned to participate in another forum organized by the Sun-Times. Other than that, the RFA fellows were unable to find time to organize community outreach outside their reporting duties. . They were already trying to cover an impossibly vast region and considered outreach and engagement as extras or nice-to-haves, rather than core reporting functions. When asked about community engagement, Fusco suggested that he associated these efforts with other departments, like marketing.

Ballesteros, Ramos, and Fusco were all enthusiastic about the value of community outreach, however. Fusco suggested that the Sun-Times’ shrinking pool of reporters made it necessary to seek new ways to engage communities:

I think in general, whether it’s the South and West Sides or other Chicago communities, we need to figure out better ways to do that, you know. It used to be the way you connected with the community is you had reporters in those communities, and they were on the street. Those days are kind of done.

Ramos explained that he was already trying to take small steps to build relationships with the community members he quoted in stories by inviting them to give feedback on his work and explaining the process he went through to make stories. He said he saw this as “putting some power into their hands,” and suggested it not only helped him to grow as a reporter, but also “allows them into your world a little bit as well.”[39] He said he’d welcome opportunities to do additional community engagement, such as holding regular public meetings to talk about story ideas. He suggested that, in contrast with the RFA-mandated service project, those sorts of activities might be easier to do and lead to more stories.

Austin focus-group participants expressed a desire for these kinds of relationships. Participants wanted to hold journalists accountable. When one participant said she had been interviewed by a journalist who she believed misquoted her, another participant suggested it would be helpful to have a way to lodge a complaint: “She didn’t have nobody to go to, to say ‘Hey, retract.’ Because some people can make you retract stuff, but some people have no power to make you retract stuff.”[40]

Participants also offered ideas for community outreach, including “office hours” held by journalists at local churches or libraries on a rotation of topics, open forums, and weekly community-journalist meetings. One group suggested journalists or editors host sessions to work on the production and editing of a story (or the layout of a paper) with community members, “So the community learns how this is done.”[41] As in Pike County, there was an emphasis on providing actionable information, such as directions to resources on health, land ownership, and finances. Finally, there was an emphasis on the need for reporters to spend time in communities even beyond coming in for an hour to get story ideas. One participant indirectly mentioned a proposal by Cook County commissioner Richard Boykin to give city employees—police officers, emergency medical technicians, teachers—free homes in “endangered communities;” he wondered if there were similar advantages for journalists. “Not saying they have to move here, but they have some stake in it, not just, ‘I’m getting the story,’” he said. “They get to know the young people in the community. They build relationships.”[42]

A hyperlocal alternative

The Austin Weekly was already meeting some of the focus groups’ demands, though they were doing so on a shoestring budget. The community newspaper’s only staff was one part-time editor, Michael Romain. But the paper collaborated with other groups like Austin Talks, a student journalism project at Columbia College Chicago; and the nonprofit civic journalism lab City Bureau. Through these collaborations, the Austin Weekly occasionally hosted community forums, such as an event with City Bureau to release the Austin People-Powered Voter Guide, which the paper produced in advance of the City Hall and aldermanic elections. In focus group discussions, several participants, including Ayesha, expressed appreciation for a story from the Weekly’s Voter Guide on candidate positions related to Austin’s Black-owned businesses:

I did feel like it was good to have a piece like this to sort of bring up other dimensions of the community, whereas I think that a lot of the mainstream, so like Sun-Times and the stations where they just have these two notes about Black communities, and particularly when it comes around election times, they’re probably hitting at those two notes. Maybe schools. Maybe crime. There is a lot of things in between, and this is an opportunity to say, “There are business owners in our communities who are looking to take advantage of the same resources that other communities have.”

Another resident, Dwayne, said the reporting was so local it made him feel directly connected to the newsroom: “What is really funny to me is that I know a nice amount of these people, and I was like, ‘What? He said what?’” Dwayne said the story showed “how people are affected by decisions made in the community,” and that it felt close to home.

Austin Weekly editor Romain says his newspaper may lack brand recognition, but it fills a gap in what was the largest community area in Chicago until 2017: “There are no real news publications or outlets that service those local community needs like we do,” he says. Romain explains the paper thrives at a “granular level.” This includes city meetings hosted by aldermen or the police, but also extends to lighter fare:

There’s value to having somebody, a local newspaper reporter at a national night out event, or, you know, local basketball tournament, so that people see more perspective about their community rather than just what’s reported on the TV news or in the large newspapers.[43]

Romain says the Weekly rarely covers crime. But he acknowledges that the Austin community has been stigmatized: “My goal is not to really change the overarching narrative, because that’s like trying to change the weather.” He says he understands why community members see “the media” in a negative light, but it makes him feel invisible. At a press conference, one resident said the press never wrote anything positive about the community. “They’ll say, ‘Look, there’s no media here.’ I just, I’m standing looking at you,” he said. Romain said people approached him after these events to apologize and explain they hadn’t realized he was there.

The people’s perception of the media in general, we get tarnished by whatever that is, you know, good, bad, or indifferent. It’s just what it is. So, at this point …I just try to do our job. You know, it’s a quiet, thankless task.

Though widespread negative attitudes toward news outlets in general reflected onto his own work, Romain said he was pleased to hear about other efforts to cover the South and West sides of Chicago. He said he welcomed new initiatives in the area and was open to exploring ways to collaborate with them.

Playing a long game

Given public perceptions of the Sun-Times and mainstream news media more broadly, was it possible for RFA to shift perspectives in Austin? Ballesteros and Ramos said they would not be surprised if residents were unfamiliar with their work. “Chicago media has done a disservice to certain communities for a long time,” Ramos said. “You can’t expect to see…the change in perception in just five to six months.”[44]

RFA’s stated goals include “help[ing] people better understand their own community, and feel better understood themselves.” But the job of changing attitudes, particularly when it comes to feeling understood by journalists, has been complicated by resource limitations. RFA’s model spread two journalists across a large region, making it difficult to cover any one neighborhood, let alone conduct community outreach. As Ballesteros pointed out, RFA fellows were operating within a larger context of resource constraints:

It’s one thing to have reporters assigned to these areas, but it’s another to really have the staff and the capability of molding and creating stories that only can come together when people have time and are, you know, not overworked.[45]

Despite these limitations, residents expressed appreciation for the small number of stories about Austin written by the two RFA fellows, once those stories were brought to their attention . But the lack of outreach and the ratio of these stories to others in the Sun-Times made it less likely for the community members in our focus groups to be aware of RFA’s efforts. When we told Austin residents that this program existed, they were enthusiastic about it—even if the reporting ended up being more about their community than for it. As Ayesha put it:

I think that’s really good, particularly because, if there’s the opportunity for people who don’t know anything about Austin to find out about Austin, if they’re picking up a Sun-Times, it’d be nice that they can have a bigger picture, a more sort of fuller picture of Austin.[46]

Because Chicago is so segregated, Ayesha reasoned that, for some residents, coverage in the Sun-Times might be the only impression they get of Austin. These representations mattered to many residents; the stories had the potential to affect outsiders’ willingness to visit or even move into Austin, to invest financially in the area, or to start a business there. So the reporting of RFA fellows, which included stories about a range of constructive community initiatives, made an intervention in the local news ecosystem by offering narratives about the South and West sides beyond terse crime reporting. RFA’s Waldman suggested the Sun-Times was playing a “long game.” To him, the responses of residents suggested that, “if other newspapers small and large invested the time in covering under-covered communities better, it would pay dividends; it would be appreciated.”[47]

Recommendations

More and more studies emphasize the critical need to strengthen local news ecosystems in order to support healthy and civically engaged communities. At the same time, interventions like Report for America and ProPublica’s Local Reporting Network have grown, partly as a result of increased philanthropic attention to local news needs. This, then, is an important moment to reflect upon what has been tried so far, and to improve upon those efforts, when possible.

Wright’s reporting on the Martin County, Kentucky water system clearly demonstrates the effect individual news stories can have when reporters are being hired to tell them. Here, though, our recommendations focus on the larger, ongoing relationship between host news outlets and the communities RFA’s fellows cover. Our study examined two very different places where RFA—and others—attempted to contribute to local news capacity. We do not offer a comprehensive assessment of RFA as a whole, but, based on themes that have emerged from these cases, offer some lessons learned and suggestions for RFA and others:

- Support coverage for communities. Offering an alternative to harmful stereotypes circulated about communities is an important contribution that projects, like RFA, already make. But those communities also need robust coverage of hyperlocal issues, and their primarily local implications, intended primarily for them. RFA is moving in this direction; the selection of fellows announced last week includes a reporter who will work exclusively on the Austin and North Lawndale neighborhoods for Block Club Chicago, a city-wide non-profit online news outlet. RFA told us they have also begun to encourage community papers and weeklies to apply. If RFA aims to reach outlets that serve marginalized communities, it will need to tell outlets about the program and its process. Otherwise, outlets that are not already looped into the circuit of journalism conferences and collaborations may not learn about it; or they may not believe that the fellowships are being offered to them.

- Balance concerns for scale with ability to demonstrate impact. For newsrooms already facing significant resource constraints, the impulse will understandably be to assign reporters to cover a wide range of communities, as is the case for the Pike County and Chicago fellows we interviewed. All the fellows interviewed expressed concerns about how to balance coverage across such large areas, particularly given limited time to build source relationships. Furthermore, our focus groups in Austin and Pike County demonstrated an almost complete lack of awareness among residents that RFA’s fellows were assigned to their region. Since improving the coverage both about and for participating communities is a goal of RFA beyond the impact of individual stories, enough sustained reporting should occur that local residents notice. For communities where trust in the hosting newsroom may already be low, it seems especially likely that if they do take notice, those communities will question the depth of the outlet’s commitment.

- Find additional opportunities to support collaborations. Collaborations offer another pathway to strengthen local news ecosystems. In Chicago, residents expressed comparatively greater trust in the Austin Weekly and a sense that it was closer to their community. If the Sun-Times wanted to deepen its connections to neighborhoods, it could collaborate with such community-based outlets through community outreach or discussions, or sharing content. While such a collaboration would be challenging in a place like Pikeville, where there is a history of bad blood, in a place like Chicago there is already a history of collaborations among news outlets. Projects like Resolve Philadelphia’s Broke in Philly or the Charlotte Journalism Collaborative suggest a growing interest in and appetite for collaborations that more holistically support local news ecosystems. RFA already informally encourages collaborations and has given outlets that apply in collaboration multiple fellows. Taken a step further, the work of encouraging collaboration could include building a robust asset map of local news and information resources throughout a fellow’s coverage area, or positioning fellows as liaisons between a single regional outlet and one or more hyperlocal outlets across the communities the fellow is covering. Of course, different locales will necessitate different strategies, and RFA is wise to retain some flexibility, as they told us, by avoiding a blanket collaboration requirement.

- Source reporters locally. Reporters coming from outside a community can bring fresh perspectives, and contribute valuable coverage for the duration of their time in an area. However, if sustainability is a priority, as it arguably should be given current challenges in local journalism, it may be advisable to look for reporters who have established connections to an area. Often, local news outlets struggle to retain local talent, particularly in smaller and more rural markets. Supporting talent already living in an area (or motivated to return to one) would likely extend the benefit to the community, because locally based fellows may be more likely to stay in an area than reporters who come in for one- or two-year fellowships. In the two RFA cases we examined, the fellows from Chicago were more likely to continue contributing to the Chicago news ecosystem than the fellow from Pennsylvania, who is likely to leave Eastern Kentucky after the fellowship ends. Locally based fellows are also more likely to draw from existing networks, which is critical when project durations are short. As focus group discussions demonstrated, community members are likely to be less skeptical of reporters from the area than fellows they perceive to be outsiders. In its 2019 class of fellows, RFA announced a new fellow for the Lexington Herald-Leader who is originally from Kentucky, and the fellow for Block Club Chicago grew up on the city’s South Side. They state, however, that only one-third of the fellows will be “reporting in a place they call home.”

- Consider supporting communities over time. One- or two-year fellowships pass quickly, especially given the time it takes new reporters to get their bearings. For initiatives that prioritize the communicative health of communities, supporting newsrooms in the same geographic region over time offers a better chance for building trust in local journalism and a culture of participation and engagement. When new fellows cycle into an area, RFA or other projects could establish transition plans to introduce new fellows to their predecessors’ work and networks. This plan could include: overlap time for outgoing fellows; a mentorship stipend for previous fellows to act as a part-time resource to their replacements; and/or the creation and maintenance of a guidebook for the local “bureau.”.

- Focus on adequate communication and mentorship support. Fellows are intended to fill a gap in the newsroom, not to help overtaxed colleagues with their current responsibilities. This can present challenges for young reporters who need strong mentorship and regular access to more senior colleagues. These challenges are particularly acute for fellows embedded in communities a long distance from the main newsroom, making strong communication key. In Pike County, Wright is fortunate to have the support of not only his editor, but also a veteran reporter based in Somerset, Kentucky, who had previously covered Wright’s 13-county area as part of a much wider swath of Eastern Kentucky. Still, the newsroom is two and a half hours away, and the regional veteran is two hours away. For RFA, it’s vital to ensure partner newsrooms have specific plans in place to support remote fellows, especially if the fellows are embedded remotely in a community that has a strained relationship with its news outlets.

- Incentivize engagement. Local news capacity-building initiatives cannot build trust when communities do not know they exist. Sustained community outreach is key to reaching residents who are not already part of core audiences and residents who use the outlet but are not aware of these initiatives. Waldman expressed reluctance to force RFA news outlets into engagement practices, though he noted that RFA has given preference to outlets that use solutions journalism training from the Solutions Journalism Network (SJN) in the Intermountain West. He told us that they might consider a similar initiative for community engagement practices in the future. While projects like RFA may find value in encouraging engaged journalism through these specialized calls with particular local partners, these initiatives might also consider how connecting with communities is positioned as a standard reporting practice across their programs, rather than a specialized addition. To that end, Waldman indicated RFA might consider engagement as a criterion for selection in the future. However, he cautioned, “I think we can do the best we can, but we also have to pick the news organizations that are doing it, and reward the ones that are thinking about it in the right way.” RFA may also benefit from considering how the service project portion of fellowships might better align with primary reporting by focusing on community engagement around the reporting itself. The service projects of the fellows in the regions we studied, largely focused on youth outreach, are undoubtedly valuable, but the fellows we interviewed had difficulty arranging and juggling these along with their other duties. Building on recommendations from residents in our focus groups, more effective opportunities might include: having visibility at existing community events; directly hosting meetings about local civic issues; establishing clear digital avenues of communication (such as texts and social media polls) between locals and the RFA fellow; working in a space with “office hours,” whether rented by the outlet or at community gathering spaces like senior citizen centers; and collaborating with local community organizations and initiatives on stories that highlight local resources available to residents—among other ideas. Regardless of approach, reporters will need time and resources to implement engagement practices.

Our study participants were eager to offer their visions for more constructive relationships with local journalists, and those visions often included direct communication to and from journalists themselves, or feedback loops, at their core.

Without additional research outside these two communities, we cannot make any claims about whether the reporting of RFA fellows has shifted narratives circulating about the communities themselves. Likewise, we are limited in our ability to make claims about the effect of reading RFA stories over time because we did not know whether study participants read the stories we shared, or if they read them but didn’t remember where they came from. And, of course, our study can only speak to the experiences of two newsrooms in two communities in what is now a much larger national project. RFA has expressed an interest in learning from these early experiences and adjusting accordingly. They seem to be doing so, notably in their recent efforts to support newsrooms offering community-level coverage, and by hiring fellows connected to their area of coverage. We are interested to see how they proceed as they train and launch a new larger cohort of fellows. Additional research into other models, like ProPublica’s Local Reporting Network, or City Bureau’s model, which combines fellows, public newsrooms, and citizen documenters, would offer valuable insights into how design and output shape community perceptions of trust in and connection to local news.

In the meantime, residents’ perspectives in Austin and Pike County illustrate the value of breaking trust down into component factors—considering how assessments of accuracy, representation, and motives can blur together, and how place and power dynamics influence these factors. As initiatives seek to strengthen local news, limited resources could be more effectively stretched by considering these factors and how they can contribute to strengthening not just newsrooms, but the communication health of communities.

Endnotes

[1] Interview with Will Wright, 7/27/18

[2] For a perspective on coverage of Eastern Kentucky: https://www.scalawagmagazine.org/2018/03/telling-tales-how-the-media-fails-appalachia/

[3] See, for example, this study which found South and West Side residents (Austin is a neighborhood on the West Side) perceived news as overly negative: https://mediaengagement.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/CME-Chicago-News-Landscape-Report.pdf

[4] Mayer, Roger C., James H. Davis, and F. David Schoorman. 1995. “An Integrative Model of Organizational Trust.” The Academy of Management Review 20 (3): 709-734.

[5] For a range of critical responses to J.D. Vance’s memoir: https://www.amazon.com/dp/B07NBJ6PL2/ref=dp-kindle-redirect?_encoding=UTF8&btkr=1

[6] Focus group-7/28/18

[7] Focus group-7/27/18

[8] “Bruce” Focus group-7/27/18

[9] “Matt” Focus group-7/27/18

[10] “Linda” Focus group- 7/28/18

[11] Focus group- 7/27/18

[12] Interview with John Stamper, 7/27/18.

[13]https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/the-crisis-injournalism-has-become-a-crisis-of-democracy/2018/04/11/a908d5fc-2d64-11e8-8688-e053ba58f1e4_story.html?utm_term=.9132aeff02c8

[14] “Bruce” Focus group 2- 2/9/19

[15] “Brenda” Focus group 1- 2/9/19

[16] “Linda” Focus group 1- 2/9/19

[17] For a discussion of RFA and other initiatives and concerns around parachute journalism: https://www.cjr.org/united_states_project/appalachia-propublica-report-for-america-nieman.php

[18] Interview with Kevin Grant, 11/10/18

[19] Focus group 2- 2/9/19

[20] “Linda” Focus group 1- 2/9/19

[21] Focus group 2- 2/9/19

[22] Focus group 1- 2/9/19

[23] Focus group-8/15/18

[24] Focus group, 8/14/18

[25] Focus group-8/15/18

[26] Focus group-8/14/18

[27] Focus group- 8/14/18

[28] Focus group- 8/15/18

[29] “Gloria,” Focus group- 8/14/18

[30] “Lee,” Focus group- 8/14/18

[31] Interview with Manny Ramos, 8/15/18

[32] Interview with Chris Fusco, 8/17/18

[33] https://www.nytimes.com/2017/07/23/business/media/chicago-sun-times-ownership.html

[34] Interview with Manny Ramos, 8/15/18

[35] Interview with Manny Ramos, 8/15/18

[36] Interview with Carlos Ballesteros, 8/17/18

[37] Focus group- 8/15/18

[38] Focus group 1- 2/16/19

[39] Interview with Manny Ramos 2/15/19

[40] Focus group 1- 2/16/19

[41] Focus group 1- 2/16/19

[42] “Lee,” Focus group 2/16/19

[43] Interview with Michael Romain, 8/15/18

[44] Interview with Manny Ramos-2/19/19

[45] Interview with Carlos Ballesteros, 8/18/18

[46] “Ayesha” Focus group 2- 2/16/19

[47] Interview with Steve Waldman, 3/18/19.

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.