Executive Summary

In 2017, we did a deep dive into mobile push alerts, publishing a report in collaboration with the Guardian Mobile Innovation Lab that looked at newsrooms’ push notification usage and strategy. But a year is a long time in the world of push alerts—and, of course, mobile phones.

As the year anniversary of our study approached this past June, we decided to conduct another round of data collection to see what, if anything, had changed. What we found is that while the basic form and appearance of push notifications may not have evolved dramatically in the intervening 12 months, it’s the strategic thinking around newsroom usage that has.

One person from the Chicago Tribune whom we interviewed for this follow-up study emphasized that her outlet’s “approach to push alerts has changed drastically.” Another from The New York Times said it was “a big moment for us as a newsroom to say: push is its own platform. It deserves to have all of the intention and critical thinking that the front page does, that the home page does.”

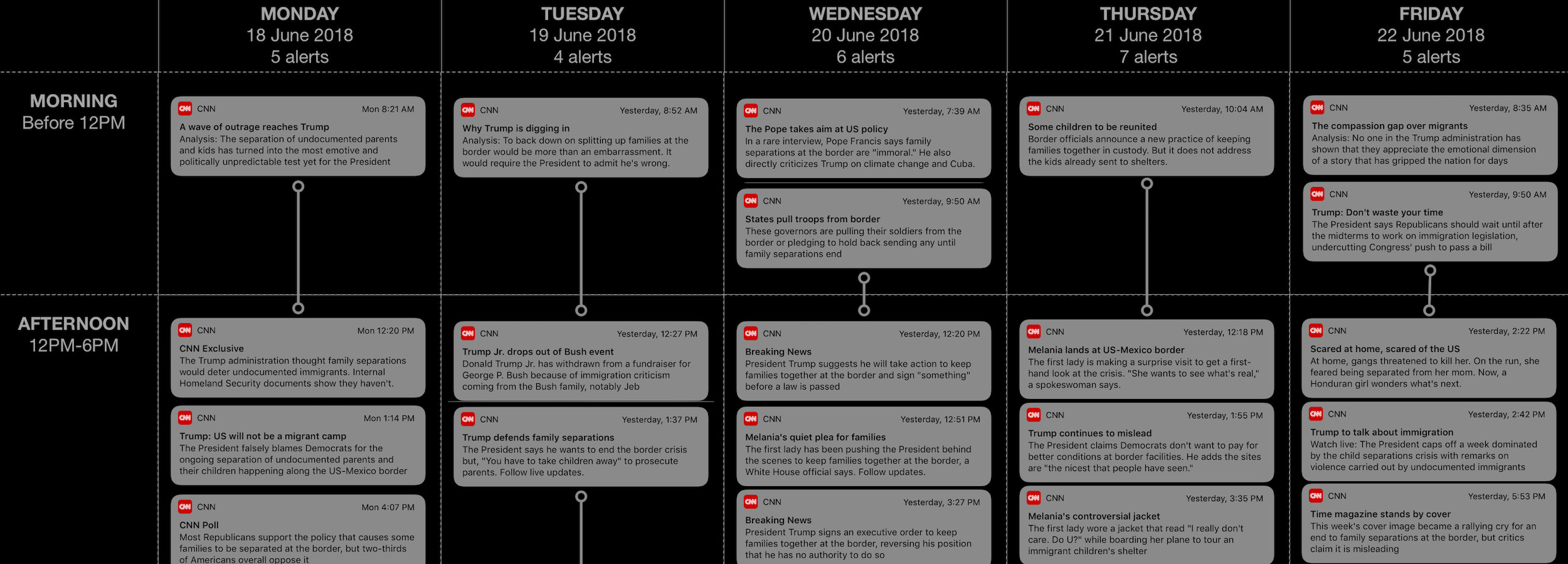

To bear witness to what this shift in thinking means in practice, this study is presented in two parts. The first, quantitative in nature, relies on a two-week content analysis of push notifications sent by the 30 news outlets we also monitored in 2017. Timing for the 2018 data collection, between June 18 and July 1, coincided with the one-year anniversary of last year’s collection period, which involved monitoring alerts for three weeks between June 19 and July 9, 2017.

The second part of this report includes a case study detailing how President Trump’s family separation policy—a story that one interviewee described as “both unique and representative of our time”—played out at the height of its controversy through mobile push alerts.

Key findings from the quantitative analysis:

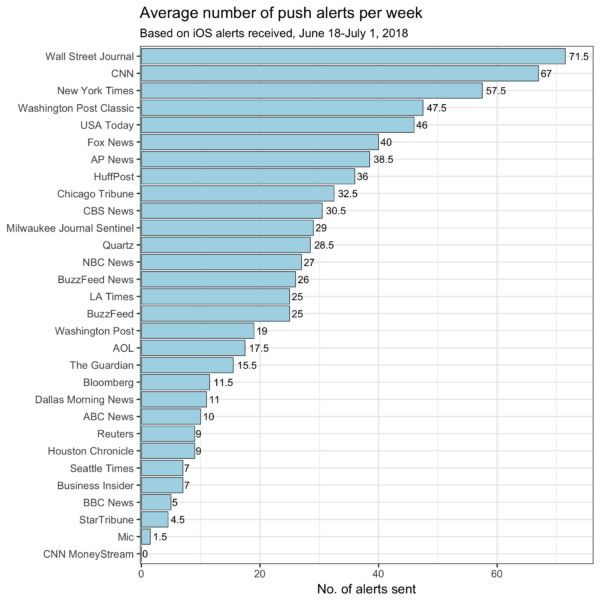

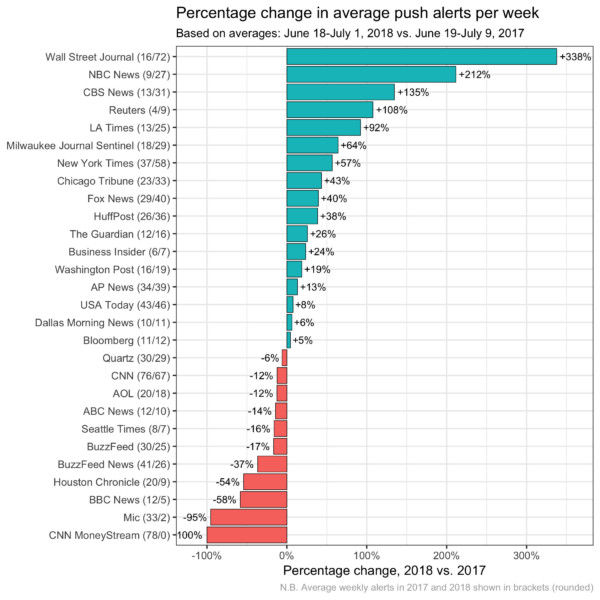

- Among the 30 news outlets in our study, most averaged more push alerts per week this year than last. The weekly average across all outlets jumped up 16 percent from 22.4 per app, per week in 2017, to 26 per app, per week in 2018.

- The Wall Street Journal claimed this year’s spot as the most prolific alerter, averaging 71.5 alerts per week and more than quadrupling its average from 2017 with the introduction of opt-in, segmented alert channels.

- There were, however, a sample of news apps that reduced their use of alerts from last year to this one. Of apps that alerted during both our 2017 and 2018 periods of study, seven sent fewer mobile pushes this year.

- The average length of alerts across the two studies, as evaluated by number of characters, has also grown since last year. Among select outlets, alert length increased by over 30 percent.

- Rich notifications containing images and video continue to remain rare, as does the use of emoji. Just seven outlets used emoji in alerts this time around, four of which were among the six found to be using them last year (Quartz, BuzzFeed, BuzzFeed News, and HuffPost).

Key findings from the case study:

- Outlets in this year’s study pushed a total of 284 alerts about President Trump’s family separation policy and border controversy during our period of analysis. The extent to which each one covered this fast-moving, extended story as it developed over two weeks varied wildly. Some apps pushed as many as seven border-related alerts in a single day, while others pushed only one over the entire period of study.

- Regional and national outlets face starkly different, but equally tricky, dilemmas when deciding which aspects of a story of this kind warrant a push alert. Brand remains among the foremost consideration in this regard, as outlets are using push to cater to their readership, and differentiate and strengthen their brands.

- In a number of cases, a single app in our sample was the only one to cover a specific development or angle of the family separation story. For instance, the Chicago Tribune alone pushed out an alert about a Chicago nonprofit housing 66 migrant kids who had been taken from their parents. Other regional outlets acted similarly, focusing on regionally specific developments in lieu of pushing every major turn in the narrative.

- This case study further confirms the ongoing shift away from using push purely for breaking news, a movement we had already observed last year. Notifications categorized as “analysis,” “general,” and “first-hand accounts” comprised over a quarter of all alerts during the family separation controversy.

- This trend sees brands actively introducing the use of less formal, conversational voice in their alerts. Once as brief and objective as possible, alert language here notably adopted a more compassionate tone, identifiable through adjectives such as “horrifying,” “disturbing,” and “heartbreaking.”

- In sum, push notifications are becoming yet another platform on which news publishers can find readers where they are, both literally and emotionally, offering a series of bite-size content that begins to construct its own record of journalistic events.

Introduction and Methodology

In June 2018, just as it neared the first anniversary of data collection for our research on newsrooms and mobile push alerts, we thought it might be worthwhile to repeat the basic parts of our 2017 analysis. The initial aim was to put together a simple 1,000-word piece comparing numbers from this year to last.

Then, on June 18, the first day of our data collection redux, both President Trump and Secretary of Homeland Security Kirstjen Nielsen made separate, inflammatory statements denying responsibility for a “zero-tolerance” policy begun earlier in 2018 that referred all adults attempting to illegally cross the US border for criminal prosecution. The policy separated more than 2,000 children from their parents, who were immediately jailed in the US upon arrival. Doubling down the next day, on June 19 President Trump and members of the GOP detailed progress toward passing a family separation bill. As this story continued to swell throughout the two weeks of our quantitative research, an obvious case study emerged for investigating how news outlets negotiate mobile alert coverage around issues as nationally controversial and long-lived as this one.

When all the data from our analysis had been collected, we wanted some explanation for what we had found. So, we got on the phone with a few people at the outlets whose push alerts we had surveyed—people who inevitably had very intriguing opinions about what had just happened from their perspectives.

In other words, the whole thing ballooned. It went from a fairly straightforward numerical follow-up to a standalone research project that aims to evaluate both quantitatively and qualitatively what has stayed static in the mobile alert landscape since last year, what has evolved, and how push notifications on a lock screen are becoming a platform unto themselves.

A note on methodology

For this study, we collected 1,510 alerts from the same 30 news apps observed last year, using an iPhone 6 located in New York City and running iOS 11 between June 18 and July 1, 2018. Where regional options were available, apps were set to receive alerts for the US. Where optional alert channels were available (e.g., politics, sports, etc.), all were enabled. As such, data presented in this study refers to the maximum number of alerts sent from each app rather than the number received by each of its users. All manual coding and categorization were conducted by the report’s author.

On completion of the coding, interviews were conducted with:

- Eric Bishop, assistant editor for mobile, The New York Times

- Phil Izzo, deputy chief news editor, The Wall Street Journal

- Marcus Mabry, senior director of mobile programming, CNN

- Marcus Moretti, VP of product, Mic

- Lydia Serota, mobile editor, The Wall Street Journal

- Elizabeth Wolfe, director of audience engagement, Chicago Tribune

Alerts Have Grown in Number and Length

Most outlets sent more alerts this year than last

As publishers introduce more subject-specific alert channels, or become more relaxed about pushing ever greater quantities of alerts through existing ones, the average number of alerts sent from the 30 news apps in our study increased year-on-year. The overall mean, as measured across all apps, grew, and more individual apps pushed more alerts than in the equivalent period last year—substantially, in a number of cases.

This even as the most prolific alerter from last year’s study, CNN MoneyStream, sent zero alerts during this recent data collection period.

Without a doubt, the overall push alert average from last year’s study—22.4 per app, per week—got a significant bump from CNN and CNN MoneyStream, whose apps averaged 76 and 78 alerts per week, respectively. Both outlets had far outpaced the other news apps, as the next highest weekly alerter was USA Today with an average of 43.

Yet despite the effective disappearance of CNN MoneyStream in the new data, the weekly average for push alerts across all outlets jumped this year to 26 per app, per week. This was up 16 percent from last year’s figure.

Overtaking the top spot as most prolific alerter was The Wall Street Journal, which averaged 71.5 alerts per week.

Four outlets more than doubled (and in certain cases tripled or even quadrupled) the number of alerts pushed via their iOS apps each week—those being The Wall Street Journal, NBC News, CBS News, and Reuters (although it should be noted that Reuters began from the relatively low base of four per week in 2017’s study).

The Wall Street Journal made by far the biggest leap upward, increasing its alerts from 16 per week in 2017 to 72 in 2018. This ambitious jump is largely because the publication introduced a raft of additional, more specialized alert channels in the intervening period. When the original analysis was conducted, users of the Journal’s app had just one option: breaking news. Now, there are eight more optional channels: featured reads, deals, markets, economy, politics, technology, science, and opinion.

Even so, this year’s average of 27.5 alerts per week explicitly labeled as “breaking news” is still a 68-percent increase on the 16.3 recorded in 2017, meaning that even Journal readers who did opt into additional channels have still received considerably more breaking news alerts than they did in the equivalent period last year.

Second to the Journal in terms of overall increase in alerts was NBC News, whose average of 27 alerts per week in 2018 was more than three times the 8.7 recorded in 2017. Unlike with the Journal, this growth cannot be attributed to the introduction of new segmenting channels. The NBC News app has only one setting for alerts—on or off. (NBC News did not respond to questions sent regarding our findings.)

Why might newsrooms be pushing more alerts?

None of our interviewees pointed to a deliberate, strategic decision to send more alerts this year than they did last year. Rather, editors with whom we spoke saw the increases as a byproduct of a range of intersecting cultural factors. Those include:

- the growing consensus that push should not be viewed solely as a platform for breaking news, but also as a means for promoting the newsroom’s strongest journalism and building brand loyalty around exclusive stories, resulting in a broader range of content being surfaced via the platform.

- more people inside the newsroom “thinking digitally,” recognizing the power of mobile alerts, and involving themselves in the process by pitching stories, suggesting push language, etc.

Meanwhile, as last year’s analysis also found, there’s a widely accepted notion that push alerts need not be exclusively reserved for breaking news. The practice has been gradually gaining acceptance among newsrooms and readers for some time now,1 and it appears to be continuing apace.

For Eric Bishop, assistant editor for mobile at The New York Times, this perceived shift in expectations has empowered the publication (whose average weekly alerts increased 57 percent across our two studies) to be more adventurous when determining what is suitable for—or worthy of—an alert.

“As we have more people around the newsroom thinking about notifications, and as notifications that are less purely breaking news become more the norm around the industry, we’ve taken more chances with the types of content we see as push-worthy. I would say that, broadly, we’re becoming more open to a greater variety of storytelling on the lock screen.”

Just as the industry and audiences have started to acclimate to the idea of non-breaking news delivered to their lock screens—and, with the increased adoption of smart watches, their wrists—the Times has taken deliberate steps to formalize strategy for pushing a wider variety of its output to lock screens, even developing a programming schedule for its enterprise journalism.

“We want to send one big enterprise story per day. We want to send a few politics enterprise stories per week, that kind of thing,” Bishop explained. This marks a significant transition in terms of the institutional mindset around push, he said, adding:

“We looked at the non-news pushes, the alerts for enterprise, and decided to put a little more structure around how we send those out, how we program them. I think that was kind of a big moment for us as a newsroom to say: push is its own platform. It deserves to have all of the intention and critical thinking that the front page does, that the home page does. So we put together somewhat of a schedule: enterprise with various buckets.”

At some outlets this broad change in culture has had a major impact on strategy. For the Chicago Tribune, whose average number of weekly alerts increased by 43 percent, it has legitimated the idea of supplementing the need-to-know of breaking news with more nice-to-know alerts. Elizabeth Wolfe, mobile editor at the Tribune, asked, “Why not tell them about news we think they’d want to read, not just need to read?”

As noted earlier, The Wall Street Journal’s vastly increased push output—up 338 percent—can be largely attributed to the introduction of additional alert categories. This has had a great impact on newsroom workflow and process, beyond just creating additional funnels for publishing alerts.

According to Phil Izzo, deputy chief news editor at The Wall Street Journal, new news categories have forced mobile editors to think differently about audience expectations. A user’s decision to sign up for a specific channel is interpreted as a signal that they have an increased desire or tolerance for those specific alerts over that of the breaking news crowd. “We feel like we can have a higher cadence on those categories because people have opted in to them,” Izzo said.“They’ve told us they want those things.”

Becoming more digitally minded

Interviewees at all three legacy publishers described how interest in and involvement with push has increased as more people in the newsroom are now “thinking digitally.” Over the course of the year between our 2017 report and today, The Wall Street Journal has “done a lot more work with [its] digital transition as a newsroom,” Lydia Serota said. “I think people have become much more aware of what we’re doing on the platform team and understand that the success of their story [comes down to] success on digital.”

The Chicago Tribune’s director of audience engagement, Elizabeth Wolfe, who said their “approach to push alerts has changed drastically over the last year or so,” attributed much of this change in strategy to her entire audience team becoming better versed in the audience data.

Bishop described the outcome of this ongoing transition at the Times by saying: “We’re just getting a lot more people who are adept at writing good notifications that work for the medium. It can be really hard, in the space of just 140 characters, to write something that feels satisfying on its own, that draws you in, that feels vivid and evocative.”

Likewise, said Izzo at The Wall Street Journal, with an adjustment toward digital came greater buy-in from the newsroom around mobile alerts. “We went from people never suggesting push language or a push to basically [having to say] to people, ‘Please stop suggesting pushes.’”

If this trend is replicating itself across newsrooms more broadly, it suggests encouraging progress in 12 months. One gripe among many people interviewed last year was that mobile editors were ploughing a lonely road with push, despite being surrounded by people with the knowledge and skills to make valuable contributions.

As one product manager put it last year, “[T]o have the people closest to the story—the writer and the editor, they know the story best, they’re dealing with one to three stories a day—suggesting language, I think would be extremely helpful for us.” For some, there have been positive developments on this front already.

Push can’t be an outlet’s entire strategy

At the other end of the spectrum, our data indicates that a number of publishers in our sample have actually scaled back their efforts around push alerts, or abandoned them completely.

One dramatic withdrawal was CNN MoneyStream. In our 2017 study, the outlet sent more alerts than any other app—an average of 11 per day—suggesting that push alerts were a central part of its strategy.

This year, however, MoneyStream did not send a single alert. (Only after our study’s completion did we received very occasional alerts from CNN MoneyStream, complete with trademark emojis.) According to Digiday, MoneyStream was a casualty of layoffs made at CNN earlier in the year and is now “just an automated feed.”

Another outlet that made a remarkable U-turn with its alert strategy was Mic, whose average number of weekly alerts plummeted from 33 to two. (In November 2018, well after the completion of our data collection, the outlet laid off the majority of its staff just before selling to Digital Bustle Group for $5 million.)

Mic’s retreat from push was particularly striking because its mobile app was initially built entirely around mobile alerts. The company appeared to be a trailblazer, providing news directly from a reader’s lock screen via detailed alerts that negated the need to open the app itself. The app’s page on the iOS App Store promised, “News you actually care about, completely from notifications.” If you were to launch the app, the presenter of an introductory splash video explained that the company had taken this approach because “nobody likes opening apps.”

When the app first launched in late 2016, then-Mic publisher Cory Haik said, “We do think we’ve hit on something with this very frictionless system of consuming the content on the lock screen . . . The idea is that you can quickly get the story without tapping in, so it should be pretty quick to get what you need to get from that notification and move on.”

So why did Mic pulled back from this approach? Partly, it seems, because mobile audiences apparently do like opening apps—or are unaware there is an alternative.

According to Marcus Moretti, VP of product at Mic, the experiment did not resonate with enough of the audience to justify continuation. “We started this experiment with rich notifications around the 2016 election and ran it for about nine months,” Moretti said. “We found that roughly 50 percent of users actually used the app in the traditional way, opening it from the home screen. Our explanation was that for many iOS users, Long Press or 3D Touch is still a novel and even undiscovered behavior.”

Mic’s findings support a hypothesis, which numerous interviewees articulated during our original interviews: that a significant proportion of mobile app users are still not accustomed to—or, perhaps, interested in—expanding alerts.

As we noted last year, “a considerable number of [interviewees] . . . speculated that there may be a general lack of awareness among the audience that alerts can be expanded. If this is the case, then it follows that publishers will not dedicate valuable resources to developing and incorporating this functionality into their products if it is not going to be viewed or deliver any kind of return.”

One mobile editor cited Apple’s design—in particular the way that engagement options and expanded images are concealed behind imperceptible interfaces such as 3D Touch—as a reason why his outlet had resisted being overly ambitious with their alerts. “There’s so much possibility there, but . . . I do think [because of] the way the [iOS] design is right now, I don’t get the sense that a lot of users even know that you can expand notifications.”

The question of how to increase awareness and encourage new behavior among audiences remains unsolved. Last year, we concluded: “There may be a need to educate audiences about the possibilities of push alerts (expanding alerts, viewing video inside alerts, etc.), otherwise at least part of the work news outlets are doing will remain unrealized.”

The outcome of Mic’s experiment suggests this conclusion may not have gone far enough. Mic’s entire app was built around the concept of delivering news via detailed rich notifications. What’s more, Mic’s core millennial audience might reasonably have been expected to be more tech- or mobile-savvy news consumers. This, paired with Mic’s effort in demonstrating the functionality of its app with a detailed onboarding video that walked users through the process of signing up for and expanding alerts, suggests there may be a ways to go before news outlets will be able to fully realize the potential of the lock screen.

In the absence of audience research, the reasons why audiences tend not to expand alerts remain unclear. Among the possibilities are that: (a) the short, unexpanded alerts are sufficient, therefore audiences do not feel it necessary to expand them (i.e., they know alerts can be expanded but choose not to do so); (b) they are not aware that alerts can be expanded; or (c) they are not seeing or engaging with alerts on any level.

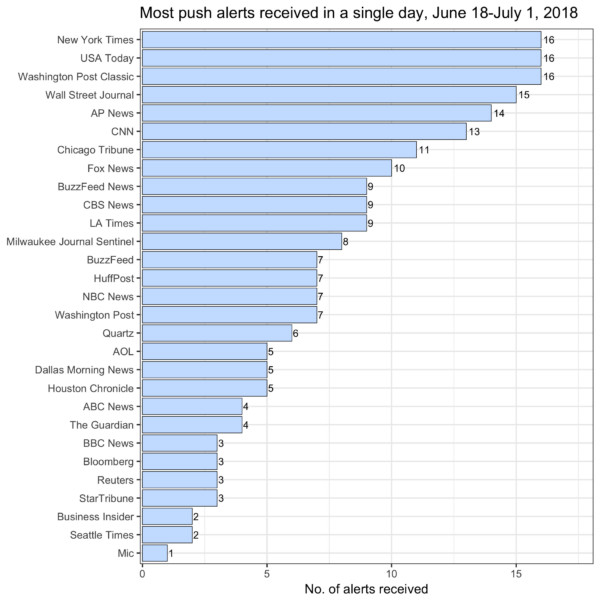

Multiple outlets pushed as many as 16 alerts in a day

A review of the most alerts sent out in a single day highlights how central push is now to newsroom practice and the extent to which many outlets have become more relaxed about pushing notifications more frequently.

Eight of the publishers in our sample sent 10 or more alerts in a single day—AP News, Chicago Tribune, CNN, Fox News, The New York Times, USA Today, The Wall Street Journal, and The Washington Post.

The average app user will not typically receive all of these alerts, of course. In the majority of cases the notifications we tracked were spread across multiple, topic-specific channels, a number of which the average user probably hasn’t enabled. Across the outlets that pushed 15 or more in a single day, The New York Times’s app has seven channels, USA Today’s has six, The Washington Post’s has 10, and The Wall Street Journal’s has nine.

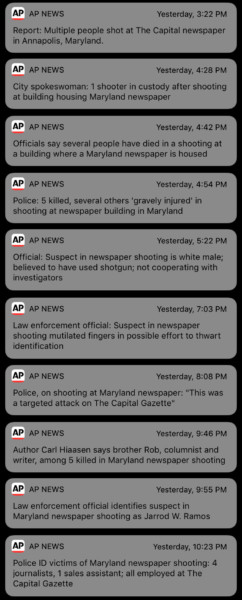

One notable exception is AP News, whose app has only an on/off toggle for alerts. The AP app did send out 14 alerts in one day—Thursday, June 28, the day of the shooting at The Capital Gazette newspaper in Annapolis, Maryland. The mass shooting was the subject of 10 of these alerts.

Ten AP News alerts about the shooting at The Capital Gazette, pushed over seven hours in June 2018.

Alerts are getting longer

Push alerts have come a long way since the days of pithy headlines designed to tempt readers into opening a publisher’s app. One audience manager interviewed last year said his outlet had moved away from this approach, primarily because they felt it “doesn’t provide voice, often it doesn’t provide enough context, and it seems very robotic and soulless.” Consequently, when we coded our original 2017 sample of 2,085 iOS alerts into distinct categories—“headline,” “additional context,” “teaser,” “round-up,” and “other”––those with additional context accounted for 55 percent of all alerts.

Over the course of our research, many editors have described a desire to deliver as much value as possible from the lock screen, ensuring their audience does not feel it necessary to tap through to grasp the importance of a story. As one mobile editor said in our original report:

I think a successful push notification is one where somebody opens their phone, looks at it, says, “That’s interesting,” and puts their phone back in their pocket. All I want is for our readers to feel like they’re informed or they’re interested. If the pushes do that, to me that’s success and that’s fine . . . We do measure success based on how many people tap on the notification, but that’s not the be all and end all to me. The be all and end all to me is: did users find this useful or not?

Between 2017 and 2018, the average length of alerts increased by 11 percent, jumping from 101.9 characters to 113.4. At the highest end of the scale, there were three outlets whose alerts increased by over one-third:

- Milwaukee Journal Sentinel (+41 percent)

- CBS News (+39 percent)

- Chicago Tribune (+36 percent)

The average alert from the Chicago Tribune jumped 36 percent from 86 characters to 116.

The Tribune also sent the second-longest iOS alert recorded in this year’s analysis—186 characters:

Supreme Court Justice Anthony Kennedy announced he is retiring after more than 30 years on the court, giving President Trump the chance to cement conservative control of the institution.

(Chicago Tribune, June 27, 2018)

The longest alert, clocking in at 198 characters, was sent by AP News:

Prominent members of the religious right are downplaying excitement on a potential Roe v Wade reversal as Supreme Court conservative shift looms. That underscores the delicate politics of the moment.

(AP News, July 1, 2018)

According to Elizabeth Wolfe, director of audience engagement at the Chicago Tribune, this increase in length is not a coincidence and has reaped rewards. “We’ve seen a noticeable increase in our direct open rate, which suggests—as we speculated—that readers prefer more in-depth alerts. We’ve also been A/B testing more conversational alerts, which are naturally longer, and have seen higher open rates there, too,” she explained.

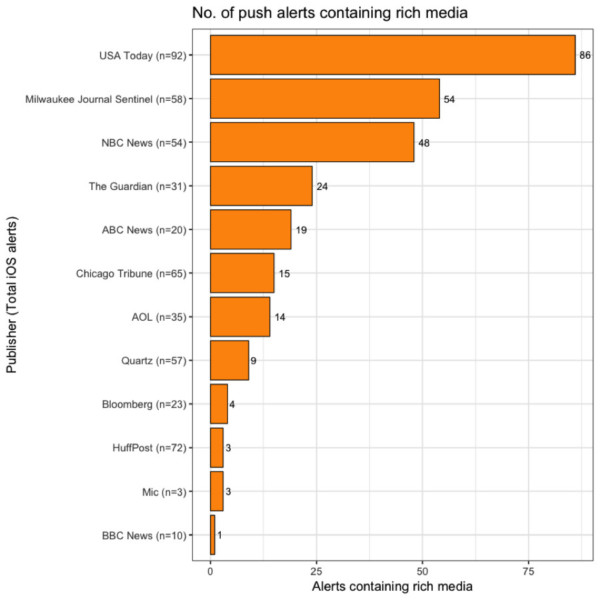

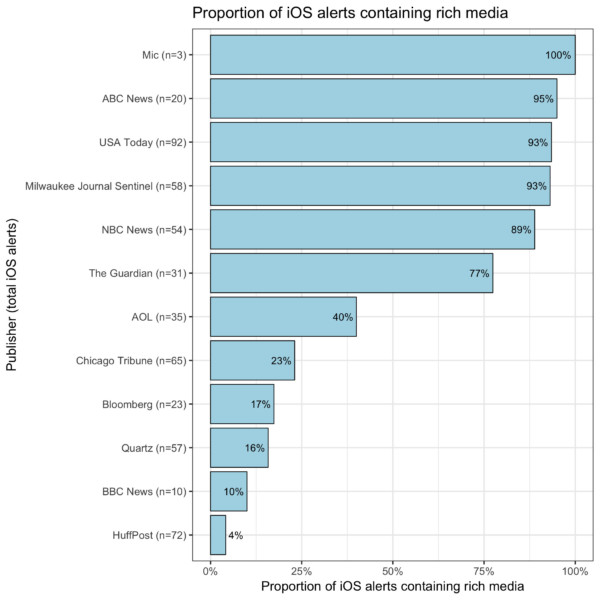

Rich notifications don’t appear any closer to taking off

The number of outlets using rich media in alerts remained static at 12, albeit with a few comings and goings as BBC News, Bloomberg, and the Chicago Tribune replaced BuzzFeed, CNN MoneyStream, and The Wall Street Journal.2

This low engagement with rich media may simply bear out Mic’s observations about tepid reaction to its rich alerts. As Izzo of The Wall Street Journal put it, “If people who have been onboarded like that aren’t expanding Mic’s alerts, what chance do we have?”

As of last year, the two Gannett apps—USA Today and the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel—were among the most consistent users of rich notifications. They were also the only outlets to use video—USA Today in 71 of its 92 alerts and the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel in 13 of its 58.

Overall, of the 12 outlets using rich notifications, only six seem fully committed to the idea. The others attached media to fewer than half of their alerts. HuffPost included photos with just three of its 72 alerts, two of which related to the border crisis (discussed in the coming case study), while just one of BBC News’s 10 alerts contained a photo.

The case for rich notifications

The Chicago Tribune is among the outlets that have introduced rich notifications in the last year, attaching photos to 15 of the 65 alerts we received over our two-week period of study.

According to Wolfe, the decision over when to use photos largely comes down to journalistic gut, but rich notifications can deliver increased engagement:

We’re including photos in roughly a third of our push alerts now, and have seen consistently higher open rates for those alerts. The alerts that would benefit from a photo usually jump out at us, so the decision doesn’t require much thought. We only add photos to alerts that actually merit a photo, because we don’t want to dilute their effectiveness.

. . . and the case against

The New York Times was among the many outlets that did not push a single rich notification during the period we observed, even though the publication has been known to do so from time to time.

As at the Chicago Tribune, the Times’s Eric Bishop said tentative A/B testing showed that alerts with photos often achieved higher engagement than those without, particularly in the Times’s earliest tests when they carried a degree of novelty value.

Despite this, Bishop gave numerous reasons why the Times has remained reluctant to make regular use of rich notifications. First, in keeping with a common complaint from our interviews last year, the Times’s production tool makes the process overly cumbersome, the result of which, Bishop said, is that they haven’t been able to develop an efficient workflow for including rich media in their alerts just yet.

Second, he questioned the value of the tiny preview images used in iOS alerts—a particularly important point if audiences are reluctant to expand alerts. This, he said, creates too many headaches for mobile editors, except in rare cases. “It’s hard to find a photo that will work at that size, that will read,” Bishop said.“Faces tend to work. If you zoom in on a face and it’s expressive, then I think that is usually pretty good.”

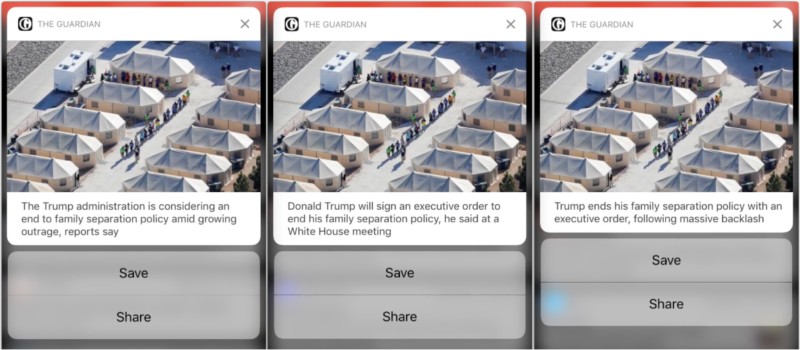

The Wall Street Journal’s Izzo also raised this point, agreeing that “rich notifications are not a great experience” in their current form. He added that compelling images are often simply not available when stories first break, and that consistent use of photos risks repetitiveness, potentially leading to alerts that are indecipherable from other outlets’ or even others of their own.

“We write about President Trump constantly,” Bishop noted. “Do you want to just see his face on the lock screen every time we send an alert on him? I’m not sure how much that adds.”

In fact, during coverage of the family separation crisis The Guardian used the same photo in three alerts pushed over the course of four hours, each covering a development in the same story:

- The Trump administration is considering an end to family separation policy amid growing outrage, reports say

(11:26 a.m.) - Donald Trump will sign an executive order to end family separation policy, he said at White House meeting

(12:32 p.m.) - Trump ends his family separation policy with an executive order, following massive backlash

(3:26 p.m.)

Three Guardian alerts received in the space of four hours, all containing the same photo.

Impediments to using photos in alerts

- Clunky newsroom tools make the process too cumbersome.

- Preview images on unexpanded alerts are arguably too small to add any value. Publishers can do little to change concerns like this in environments mostly controlled by Apple and Google.

- Sizable chunks of the audience may be reluctant to expand alerts or be unaware that they can, meaning that full-size photos may go unseen and unappreciated.

- There is always the risk of repetition when using too many similar-looking photos in subsequent alerts about the same developing story.

Case Study: Covering Trump’s Family Separation Policy with Push

The biggest story to emerge during our two-week data collection period centered on President Trump’s family separation policy.

This was a major, multi-faceted, and rapidly evolving story—one that Marcus Mabry, senior director of mobile programming at CNN, described as “both unique and representative of our time.” It generated a seemingly endless swath of newsworthy—that is, potentially push-worthy—angles and developments. Over multiple days it forced mobile editors to grapple with many of the questions they usually face, just not at the level of the individual story:

- Which developments warrant a breaking news alert?

- Is there a risk of over-alerting the story?

- What’s the correct balance between what audiences need to know about the story and what they want to know?

- Which features/analysis should be pushed and why?

- Would rich media add value to the alert? If so, which photo/video and why?

Given the decisions at play, the varying perspectives that different outlets have when covering this story via push provides a prism through which we can examine different strategies in microcosm.

Through the course of the following case study, we consider the approaches of 27 news apps. Scattered throughout are insights from four outlets, each of whom has a different approach to pushing stories such as this, mostly due to differences in their respective audiences and/or business models:

- A free, general-interest news outlet (CNN)

- An international, subscription-based, general-interest news outlet (The New York Times)

- A regional, subscription-based news outlet (Chicago Tribune)

- An international, subscription-based, specialized news outlet (The Wall Street Journal)

Different outlets used push in markedly different ways

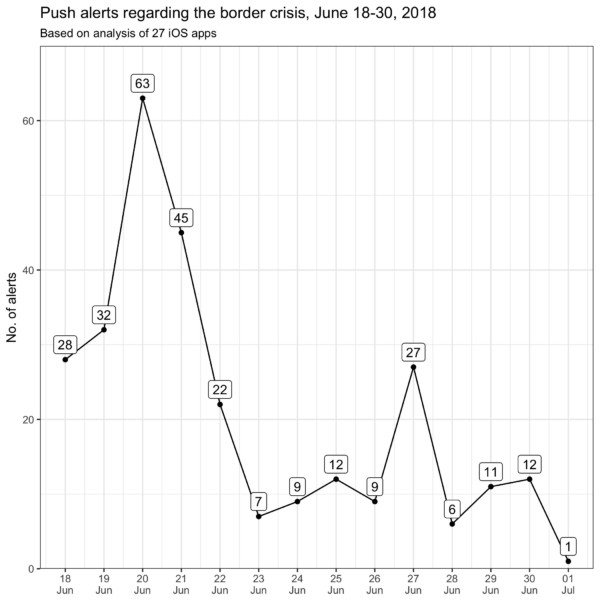

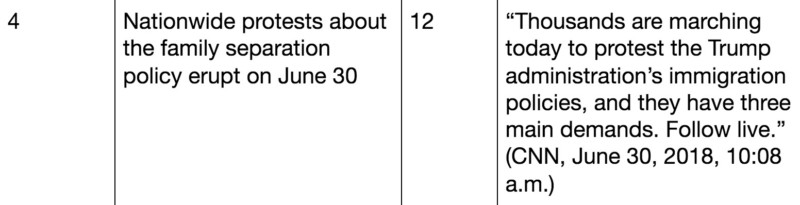

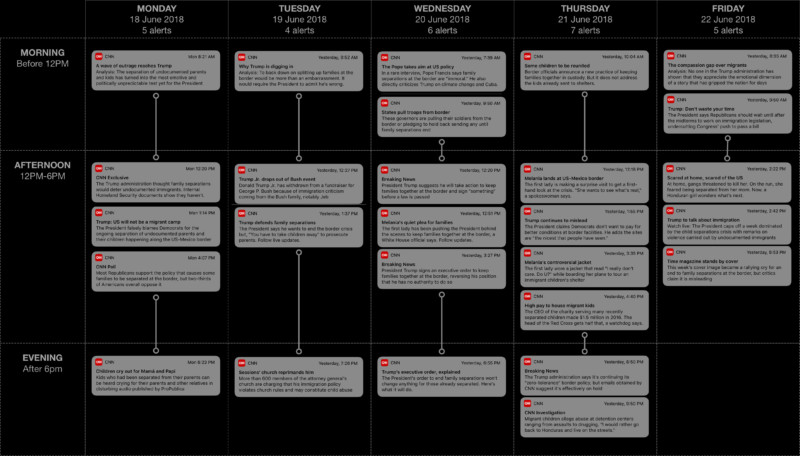

During our two weeks of analysis, a total of 284 alerts about the border and family separation crisis were pushed out, ranging from a high of 63 on June 28 to a low of one on July 1.

The first four days—Monday, June 18 to Thursday, June 21—were particularly hectic, thanks to:

- Separate, inflammatory statements from Donald Trump and Kirstjen Nielsen about the dire situation at hand (June 18).

- Trump and GOP statements about progress toward passing a bill to keep families together, and Fox television network stars speaking out against Fox News’s coverage (June 19).

- Reports that the White House was preparing the bill, an update that Trump was expected to sign the bill, and the eventual signing (June 20).

- Melania Trump’s first visit to an immigrant children’s shelter, and the fallout from her choice of jacket, which said, “I REALLY DON’T CARE, DO U?” on the back; and the postponement of a vote on new immigration legislation (June 21).

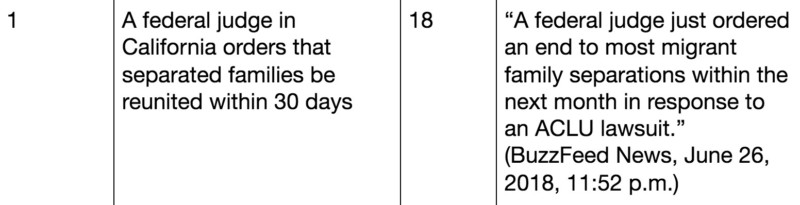

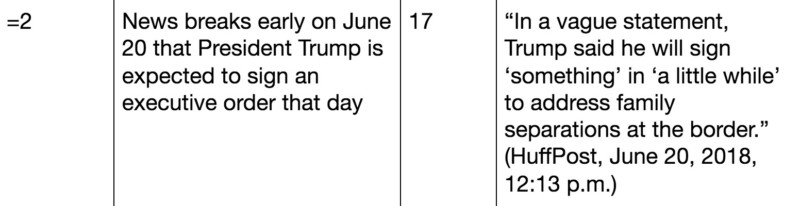

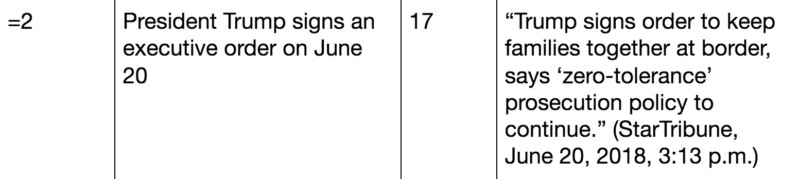

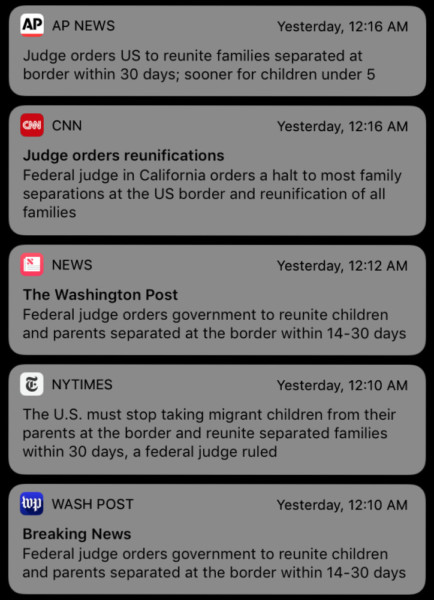

Another spike occurred on Wednesday, June 27, when a federal judge in California ordered that separated families be reunited within 30 days (the earliest alerts for which landed late on June 26), and the House rejected a revised GOP immigration bill endorsed by President Trump.

The extent to which different news outlets covered the various aspects of the border crisis via push varied greatly. Some only pushed alerts about the very biggest developments, such as when Trump signed the executive order keeping families together on June 20. However, a significant number were far more prolific, providing something akin to a running commentary on developments directly from the lock screen.

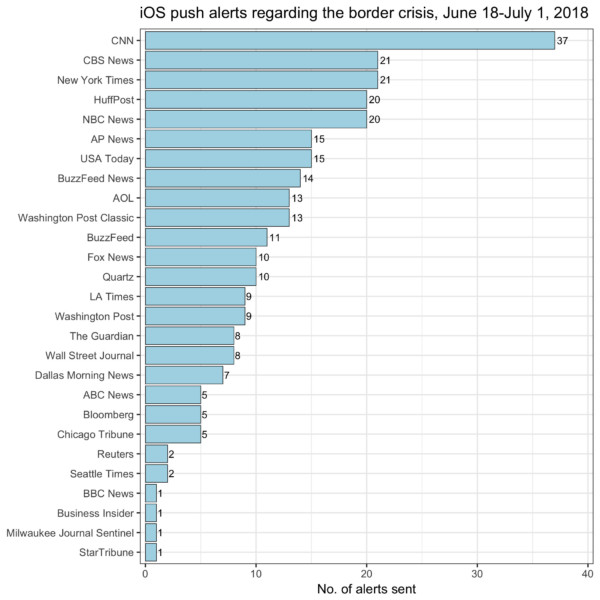

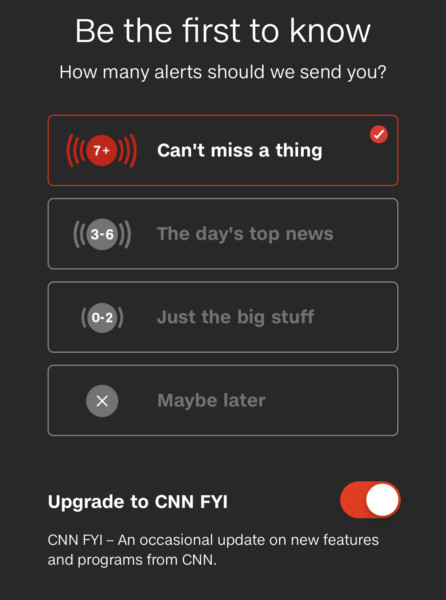

CNN pushed by far the most alerts regarding the border crisis—37 over the two weeks, at an average of over 2.6 per day. Seven other outlets averaged at least one per day—CBS News, The New York Times, HuffPost, NBC News, AP News, USA Today, and BuzzFeed News.

The remarkably high number of alerts from CNN is not surprising, given that the main alert setting on its iOS app pertains to volume/frequency. With the highest setting enabled—“7+ Can’t miss a thing. All news alerts”—it stands to reason that this high-profile, multi-faceted, fast-moving story would be the focus of numerous alerts.

The willingness among outlets to push a number of alerts about the same story should also not be too surprising. During our original interviews, there was a groundswell around the idea that audiences now have an increased tolerance for frequent alerts and a busy lock screen. This capacity allows publishers the freedom to be more liberal with their alerts without fear of causing alert fatigue. In short, if the news is relevant enough, then it warrants an alert, regardless of how many have come before.

One mobile editor described this changing mindset to us last year, saying:

We’re no longer scared of inundating people with alerts because we think we’re going to annoy them. I think we’re moving away from that. People are using so many other apps, whether it’s Snapchat or Instagram or WhatsApp, for communicating. Everybody always has a million notifications on their phone.

This viewpoint comes into even sharper focus during fast-moving stories. Indeed, five different outlets sent five or more alerts about the family separation story in a single day—CNN (four times), CBS News, HuffPost, NBC News, and The Washington Post.

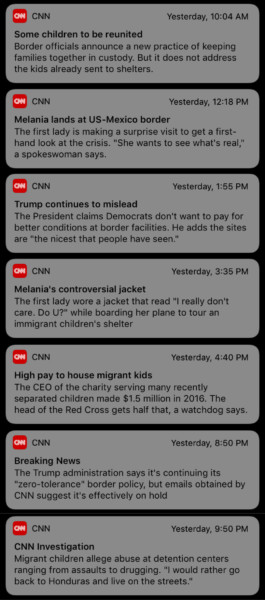

CNN sent five or more alerts about the border crisis on four of the five days between June 18 and 22, peaking with seven on June 21. On June 20, CBS News, CNN, HuffPost, and NBC News all sent five or more alerts relating to the border policy.

Seven CNN alerts about the border crisis pushed on June 20, 2018.

In the not-so-distant past there would have been considerable handwringing over whether this level of coverage constituted “over-alerting,” thereby risking users unsubscribing from alerts, uninstalling the app, or disengaging from the story. However, as noted before, this is an area where many newsrooms have become much more relaxed.

And if ever there was a story that warranted frequent alerts, it was this one. Not only were there a seemingly endless barrage of twists and turns to report, but the complex nature of the story, a convoluted puzzle comprising numerous interlocking narratives, generated ample opportunities for explainers, analysis, and opinions—the best of which would become prime candidates for push alerts.

The sheer variety of relevant output from the newsroom warrants the attention, said CNN’s Mabry, recalling:

A number of elements came together in the family separation: spot news developments, enterprise that happened to land those days, and alerting to our own live blog of the daily story. If you look at the alerts that we sent, you’ll see that there are news points that we felt were so important we had to alert them: the public outrage reaching a level that reached the president; Trump’s comments on the crisis; our own poll; our exclusive reporting on the DHS documents; the ProPublica audio. And that was just one day.

The breaking news

As was expected from any major story, there were numerous developments in the border policy and family separation narrative that received push alerts from multiple outlets.

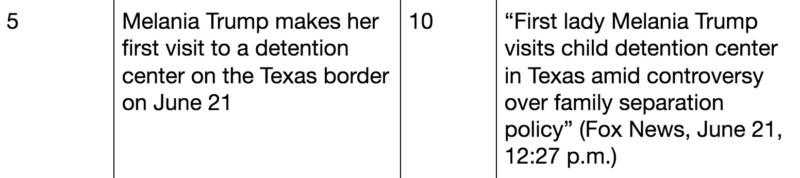

The top five most alerted developments between June 18 and July 1, 2018, were:

A flurry of breaking news alerts about the family separation crisis in the early hours of June 27, 2018.

In addition to those widely pushed breaking news events, there were a significant number of notable deviations among outlets, especially instances where some opted to push more left-field stories they felt suited their brand and would resonate with their audiences.

This was not a one-size-fits-all story. The experience of following the border policy story from the lock screen was, in many cases, markedly different from one app to the next.

Some of this may have been simple branding, catering aspects of the story to targeted readership. One way this manifested itself was regionally. For example, the Chicago Tribune and The New York Times were the only two outlets, respectively, to push the following developments:

Chicago nonprofit confirms it’s housing 66 migrant kids separated from parents under Trump’s “zero tolerance” policy: “These children are scared when they arrive at our doors.”

(Chicago Tribune, June 22, 2018)

The crisis at the southern border has reached New York, as children separated from their parents are quietly being sent to shelters here.

(The New York Times, June 20, 2018)

Elsewhere, HuffPost frequently sought to highlight the plight of the detained children, and was the only outlet to push the story of border officials stripping detained children of their possessions and an exclusive about detained children reportedly being forced to take drugs.

Kids at the border are being separated from more than their parents—officials are taking their toys too.

(HuffPost, June 20, 2018)

Shocking documents obtained by HuffPost allege that detained migrant kids have been“compelled” to take psychotropic drugs without parental consent.

(HuffPost, June 20, 2018)

CBS News was alone in alerting its audience to a public appearance from Paul Ryan:

Lawmakers are scrambling for a way to end the controversial family separation policy at the border. Speaker Paul Ryan is speaking with reporters.

(CBS News, June 20, 2018)

Meanwhile, only CNN pushed an alert about reports of Melania Trump’s “quiet” influence on policymaking and highlighted a piece about resistance from governors in border states:

The first lady has been pushing the President behind the scenes to keep families together at the border, a White House official says. Follow updates.

(CNN, June 20, 2018)

Governors won’t keep National Guard on border: These governors are pulling their soldiers from the border or pledging to hold back sending any until family separations end.

(CNN, June 20, 2018)

Not everyone went push crazy

While many outlets pushed a substantial number of alerts about various different facets of the border crisis, plenty of others did not. In fact, four outlets pushed just one alert during the entire two-week period—BBC News, Business Insider, the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, and the Star Tribune.

All four pushed their only alerts on June 20, when news broke that Trump would, and eventually did, sign an executive order. These outlets did not push stories about any other other aspects of the story during the period of our analysis.

Trump says he will sign executive order soon to “keep families together.’’

(Business Insider, June 20, 2018)

BREAKING: President Trump is expected to sign an executive order that would keep migrant families together at the border.

(Milwaukee Journal-Sentinel, June 20, 2018)

Trump signs order to keep families together at border, says “zero-tolerance” prosecution policy to continue.

(Star Tribune, June 20, 2018)

Breaking News: President Trump caves in to public pressure signing order to stop separating migrant children from parents entering US illegally.

(BBC News, June 20, 2018)

The role of brand in identifying push-worthy developments

Many of the regional outlets in our sample were among the more conservative in terms of the number of alerts pushed around the border crisis.

The Chicago Tribune (five), The Seattle Times (two), the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, and the Star Tribune (one each) all sent five or fewer over the two weeks.

As Elizabeth Wolfe of the Chicago Tribune explained, regional outlets face a quandary when deciding how extensively to push alerts about major national or international stories:

As a regional news outlet, it’s always felt like kind of a crapshoot alerting national news. We don’t know how many other news apps our alert readers receive. Are we sending them the same news they’re getting from CNN or AP? Or are they counting on us to tell them everything that’s going on in the world? From looking at our uninstalls, it’s pretty clear that people prefer to get regional news from us.

Obviously, there are some national stories that are so important and universally relevant, we’re going to alert them no matter what, though we do try to localize such news as much as possible. That, however, is an effort by the entire newsroom that begins at story ideation.

For bigger general news outlets, whose audiences want to be kept abreast of developments in major national or global stories, dilemmas over what to push carry different considerations.

Rather than concerning themselves with whether their audience is getting alerts from elsewhere, larger outlets have to try and strike the fine balance between (a) informing the audience about developments that editors feel are need–to-know and (b) providing the depth of coverage they think their audience wants to know about, while ensuring that (c) they don’t annoy people by over-alerting.

This comes into sharp focus when an ongoing barrage of potentially alert-worthy material is pouring into the newsroom. The New York Times’s Bishop admitted that this is a nice problem to have, but said:

One challenge with a story like this that is that sometimes you have so much. Sometimes that means that you’ve got the metro desk with their story saying, “The border crisis has come to New York,” the national desk has a great on-the-ground reported piece from the border, the DC bureau has an exclusive on the inner discussions of policy in the White House, and we have to make decisions about,“OK, which of these do we think is the biggest priority for an alert?”

A number of inputs factor into that decision. The first, said Bishop, is “classic, old-fashioned news judgement”—calls that can involve input from multiple parts of the newsroom because they are “often reflecting the judgment of the top editors at The New York Times.”

Another factor is the front page, which while “certainly not the only input,” he explained, is “a signal that the highest echelon of this news organization has said that this is what they think is important for our readers to see. So sometimes we use their judge as a proxy for what we should be notifying our readers about.”

CNN’s Mabry emphasized the collaborative nature of this decision-making process, breaking down the CNN programming team’s key considerations as follows: How big is the news? Is it breaking? Is it surprising? Is it big enough to lead our home pages? Our competitors? Our television shows? Our competitors? Print font pages? Is it a story of national or international importance?”

Alerts that perform well among one segment of the audience (e.g., those that have opted-in to the highest volume of alerts) sometimes also get re-posted to another, Mabry added.

There’s also the question: to whom do you push?

Another consideration for mobile editors conscious of over-alerting aspects of a major story is deciding whom to push alerts to: for which segments of the audience are they relevant? Which ones are most likely to appreciate them?

This is particularly relevant to outlets with large national and international audiences. To address this precise issue in its coverage of the border crisis, The New York Times implemented a degree of geo-targeting, with some alerts “only go[ing] to our readers in the United States, where this was a much bigger story than it was abroad.” Likewise, the developments regarding New York were targeted only to the New York audience.

Alternatively, the CNN mobile app’s settings help create audience segments based on users’ self-identified appetite for alerts, which helps the programming team appropriately cover evolving stories like the border policy crisis. “The challenge is that we want to alert every important turn in a major story,” said Mabry. “At the same time, we don’t want to overload audiences, especially audiences that are less engaged with the story. The high-frequency alert category allows us to meet that first demand and not overload other audiences.”

Even with this flexibility, there still remains a big question mark over which category—and, by extension, audience segment—a piece of news gets placed into. Addressing this is also a group effort, Mabry said.

On the importance of brand

As we noted in our original report, it is difficult to overstate the role of push alerts in building and maintaining brand loyalty. And branding is a key consideration when contrasting the decidedly different approaches outlets take to covering the same news event. The priorities and expectations of The Wall Street Journal’s audience—many of whom will primarily subscribe for coverage of core topics such as markets, finance, and business—are reasonably very different from those of more general news outlets like, say, the AP or CNN.

Establishing the sweet spot for alerts on big stories that fall outside the realm of an outlet’s core areas can be challenging for specialist news outlets. From this perspective, it is perhaps unsurprising that the number of alerts about the border story—eight—sent out by The Wall Street Journal was more comparable to the number sent by more specialized outlets like Quartz (10) and Bloomberg (five) than to its traditional print rivals, The New York Times (21) and The Washington Post (13).

Phil Izzo, mobile editor at the Journal, said of the border crisis story:

It’s a tough one for us. It’s obviously important. It’s one of the most important stories in the country, but it’s a little bit less of [interest to] our core readership than, say, […] Time Warner/ATT merger in some ways. I don’t want to sound callous when I say that, because we do care about it deeply, and our readers care about it deeply, but it was not necessarily the top story on our site every day. We were consciously not alerting on every single development—we were looking for the opportunities where something major happened that changed the debate: […] moments where Trump said something, [or] Kristjen Nielsen made a statement that reversed something. We tried to do it at major turning points as much as we possibly could.

Alerts about the border crisis pushed by The Wall Street Journal.

As with CNN’s volume-based audience segments and the Times’s geo-targeting, here is another instance where audience segmentation came into play. Of the eight alerts pushed by the Journal, three went to the main breaking news category and five went to people subscribed to the politics channel. Serota called this “the perfect example of our strategy in these situations, where the big developments everyone needs to know about go to the breaking news category, and the smaller, more incremental developments go to just the politics list, for people who are really going to want to follow all the twists and turns.”

Themes and trends across push coverage of the border crisis

1) Looking a long way beyond breaking news

A notable theme to emerge from the slew of alerts about the border policy was outlets’ willingness to push a broad variety of content extending far beyond the latest breaking news.

Overall, more than a quarter of alerts were categorized as either “analysis,” “general,” or “first-hand accounts” (27 percent between them).

The relatively large proportion of alerts dedicated to analytical pieces and other features about the border crisis shows publishers’ willingness to use push for the purpose of promoting a wider variety of core output, particularly content that draws upon their institutional strengths.

In many cases alerts were explicitly labeled to indicate that they linked to analytical pieces, rather than breaking news:

ANALYSIS: The Art of No Deal: Why Trump doesn’t want an immigration bill.

(NBC News, June 22, 2018)

Why Trump is digging in. Analysis: To back down on splitting up families at the border would be more than an embarrassment. It would require the President to admit he’s wrong.

(CNN, June 19, 2018)

Trump cranks up the rhetoric. Analysis: When an executive order and blaming Democrats failed to end the worst crisis of his political career, Trump returned to a familiar tactic.

(CNN, June 25, 2018)

Fact Checker: Breaking down the Trump administration’s claims on why families are being split at the border.

(The Washington Post, June 19, 2018)

Other examples, not explicitly labeled, included BuzzFeed’s linguistic analysis of 11 discursive techniques Trump used to depict immigrants:

“Infest,” “rapists,“ “shithole”: Trump has frequently used language that dehumanizes or vilifies immigrants.

(BuzzFeed and BuzzFeed News, June 19, 2018)

2. First-hand accounts

One type of non-breaking news alert notable for its prevalence were those we categorized as first-hand accounts (so named because they were deliberately crafted to foreground interviews with people directly affected by the crisis). Nineteen of these alerts were identified.

Within this sub-group of alerts, one stylistic trope stood out due to its frequency and the striking number of outlets that employed it: the two-part alert beginning with an emotive quote from a person directly affected by the crisis. This formula was utilized in eight of the 19 alerts categorized as first-hand accounts.

“I just came to this country to protect my children.” Migrant parents, some separated from their kids, face an uncertain future at the border.

(CBS News, June 18, 2018)

“I can’t go without my son.” The problem of separating immigrant families gets worse, as some parents are being deported without their children.

(The New York Times, June 18, 2018)

“If they take my son from me, I would die.” Trump’s family separation policy has asylum-seekers fearing for their children.

(BuzzFeed and BuzzFeed News, June 19, 2018)

“He’s all I have left”: Immigrants crossing into the US are unaware and stunned by family separations.

(USA Today, June 20, 2018)

“He was just howling and he wouldn’t move”: A foster mother takes migrant kids into her home.

(NBC News, June 20, 2018)

“I feel like I’m going to die. I feel powerless.” Many migrant mothers separated from their children have no idea how to get them back.

(The New York Times, June 22, 2018)

“I thought I’d never see them again.” Watch the reunion of a Guatemalan mother and her children, separated at the border 40 days ago.

(The New York Times, June 29, 2018)

Another variation of the same involved highlighting the first-hand nature of a story via a powerful, paraphrased quote in the alert headline:

“Scared at home, scared of the US”: At home, gangs threatened to kill her. On the run, she feared being separated from her mom. Now, a Honduran girl wonders what’s next.

(CNN, June 22, 2018)

The Times’s Bishop observed that first-person alerts foreground the human aspect of a story. “I’ve noticed that alerts that really hone in on individuals and their stories really tend to draw people in,” he said. “I think that’s a lesson that we have observed from the way that we promote stories on social media: zooming in on human narratives really works there and it can often really draw people in on the phone lock screen, too.”

Alerts like these usually pass what one mobile editor interviewed for last year’s report described as the “dinner conversation test”—the base requirement her outlet’s alerts needed to meet, whereby “someone can read your push alert and grab a tidbit that they can then talk to their friends at dinner about without needing to tap into the story and read the whole thing.”

Finally, by signaling to readers that the outlet has reporters on the scene engaging with people directly affected by the story, it reminds the audience who the outlet is and what they do best—a finding indicated by interviewees’ frequent references to using push to direct their audience towards their “signature content” and “what makes us what we are.”

Bishop noted, “I think that with a lot of these . . . we were really in these places where these stories were happening, and so obviously that’s something we’re proud and something we try and highlight—it’s something that makes us unique.”

This “one-two punch” is, he argued, “a recipe for a successful notification”:

Part 1: “I can’t go without my son.” “I do think that that is a way of sort of gesturing at and telling the human aspect of the story, but then also telling somebody just sort of a concrete fact.” Part 2: “The problem of separating immigrant families gets worse, as some parents are being deported without their children.” “The second part of that second sentence is kind of newsy: you can read that and say, ‘Oh, I didn’t know that was happening,’ and turn to the person next to you and say, ‘Did you know that some of these people are getting deported?’” |

| Strengths of a well-executed “one-two punch” push alert

• Highlights that the news organization has reporters on the ground, in the place where the story is developing. • For big organizations promoting stories from afar, it helps to remind their audience of the depth of their reach. • Brings out the human narrative, helping readers understand the situation and empathize with those affected. • Achieves the double goal of: (1) foregrounding the human aspect of the story and bringing it directly to the lock screen, while still (2) delivering a useful, interesting nugget of news. • Has a solid track record of drawing readers into the story. |

3. Bringing a human voice to a human story

In our original interviews, publishers said they wanted to shift toward a more “conversational” tone in push alerts. The rationale for this shift varied from one outlet to the next, but it was typically grounded in wanting to add more character and voice to their alerts.

In our more recent findings, there were numerous instances where outlets clearly and noticeably injected voice and personality into their notifications, often adding an empathetic voice to describe the most emotionally charged, human stories.

For example, when ProPublica released audio recorded inside a US Customs and Border Protection facility, multiple outlets pushed alerts carrying a compassionate tone, identifiable through adjectives such as “horrifying,” “disturbing,” and “heartbreaking”:

In horrifying new audio from a Border Patrol facility, children can be heard sobbing for their parents as an agent jokes,“We have an orchestra here.”

(HuffPost, June 18, 2018)

Kids who had been separated from their parents can be heard crying for their parents and other relatives in disturbing audio published by ProPublica.

(CNN, June 18, 2018)

“Papá! Papá!”: Immigrant children at detention center cry for parents in heartbreaking audio.

(USA Today [Apple News], June 18, 2018)

Other examples of lively, emotive language in alerts were plentiful, particularly among digital natives with a younger target audience:

In a stunning display of overt racism, Mike Huckabee appeared to equate migrant children separated from their families with MS-13 gang members.

(HuffPost, June 23, 2018)

The heartbreaking case of the 3-year-old boy in immigration court, and more stories from the border in today’s morning update.

(BuzzFeed News [Apple News], June 25, 2018)

4. Covering the border crisis with rich notifications

Nine outlets used media in one or more of their alerts about the border crisis. USA Today embedded rich media into 14 of their 15 alerts (11 with videos, three with photos) and The Guardian attached photos to all eight of its alerts.

By far the most consistent proponent of rich notification was NBC News, which attached photos to all 20 of its border crisis alerts.

Of these, half were photos of high-profile figures: seven of President Trump, one of Melania Trump (after her unannounced visit to a child detention center in Texas), one of Seth MacFarlane (following his criticism of Fox News’s coverage), and one of Senator Lankford appearing on Meet the Press. The other 10 showed images of people directly affected by the crisis, often either alone and isolated, or huddled together in large groups.

Twenty rich notifications about the border crisis pushed by NBC News.

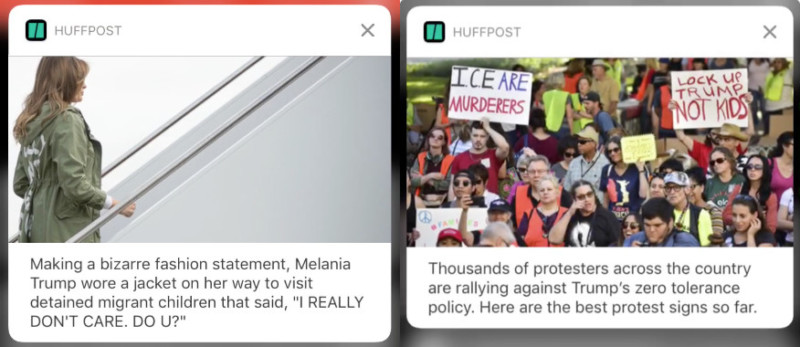

Unlike NBC News, HuffPost does not typically use rich notifications. Like the Chicago Tribune and The New York Times, the outlet is selective about when and why it adds a visual element to alerts. In fact, just three of its 72 alerts (four percent) pushed during our two-week study contained photos. Two of these were alerts about the border crisis—one about Melania Trump’s decision to wear a jacket emblazoned with the phrase, “I REALLY DON’T CARE, DO U?,” and the other a rundown of protest signs from the Families Belong Together March.

Here it seems clear why rich notifications were used. In both cases the images were the news—or at least part of it. They also acted as a kind of tease, signaling to readers what was on offer if they tapped through to the story: visual proof of Melania Trump’s jacket and an explanation of its origins; and other placards from the protest march, as promised in the accompanying text, “Here are the best protest signs so far.”

Rich notifications from HuffPost.

The photo and text combine to tell the bulk of the story on the lock screen, even down to the classic “five W’s”:

|

Conclusion

Extrapolating from our two data analyses and recent interviews with those working within major national news outlets, it feels fair to assess that mobile push alerts are doing just fine. In fact, most signs point to growth: the majority of the outlets in our study averaged more alerts per week in 2018 than in 2017, and the weekly average across all outlets jumped from 22.4 per app last year to 26 this year.

Alerts, on the whole, got longer, growing by nearly a third among some apps. They also gained more distinctive and conversational voices, as determined by individual outlets catering to audiences they hope to know well. The value newsrooms are now placing on push, in terms of its capacity to build brand and help strengthen relationships with their readers, seems to be stronger than ever.

Over the past year, there were, of course, setbacks.

In 2017, Mic tried to innovate on its own terms and use the push medium in a way that nobody else was: by asking its audience to access news directly from their phone’s lock screen through detailed alerts that negated the need to open the Mic app itself. What the outlet discovered, not soon enough, was that even its millennial audience wasn’t ready to abandon habitual behavior and embrace a totally different approach to push.

Forced to forgo its “radical” experiment long before the company laid off most of its newsroom staff and sold to Bustle at the end of November, Mic is proof that one of the biggest remaining hurdles for news outlets in the push space is navigating an environment that they don’t own—one where they can’t define the consumption habit of mobile audiences.

Norms around push—their form and function, how users become accustomed to engaging with them, the upper limits on how much product teams can innovate—are largely dictated by Apple and Google. News audiences may only accept changes to the status quo when forced into it by adjustments to their mobile operating systems.

Beholden to tech companies and the design limits of mobile platforms, even the most innovative news outlets can only do so much.

But we shouldn’t dwell on this. Especially as news outlets continue to make great strides with mobile alerts in their own environments. While it would be irresponsible to generalize from our small set of interviews, it was striking how each of the legacy publishers pointed to tangible improvements in the ways their newsrooms are thinking more “digitally.” This change has elevated the position of push alerts in the newsroom, encouraging people from across departments to suggest stories and involve themselves in crafting language for alerts. Audience teams, using their deeper grasp of metrics to better understand audiences’ appetite for different types of push alerts, have also gotten onboard.

It is encouraging to see push regarded as a platform in its own right. Not only does it provide a direct line to news organizations’ most loyal and engaged audiences, it remains free from the volatility of algorithm changes that plague publishers across other platforms. For these two reasons alone, mobile push alerts should be cherished. To date, it seems they are.

Footnotes

- This said, one person interviewed for this piece did note that parts of their audience are still not fully acclimatized to this more varied use of push, observing: “When we send something that has a little bit more of a feature-y feel to it, we do still get readers saying, ‘Why am I getting this? It’s not breaking news,’ even though we’re not saying it’s breaking news. The medium just has such a strong association with breaking news that I think that it’s still a product challenge for us and others to figure out.”↩

- The Washington Post has begun using rich notifications since this study was conducted.↩

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.