Executive Summary

Too often we tend to hear one single narrative about the state of newspapers in the United States. The newspaper industry is not one sector. While there are considerable variances between the myriad of outlets—whether national titles, major metros, dailies in large towns, alt weeklies, publications in rural communities, ethnic press, and so on—a major challenge for anyone trying to make sense of industry data is its aggregated nature. It’s nearly impossible to deduce trends or characteristics at a more granular level.

The story of local newspapers with circulations below 50,000, or what we call “small-market newspapers,” tends to get overlooked due to the narrative dominance of larger players. However, small-market publications represent a major cohort that we as a community of researchers know very little about, and a community of practitioners that too often—we were told—knows little about itself.

Our study seeks to help redress this recent imbalance. We embarked on our research with a relatively simple yet ambitious research question: How are small-market newspapers responding to digital disruption?

From the data collected in our research, we also strove to report on the future of small-market newspapers by asking: How can small-market newspapers best prepare for the future?

Our research findings are based on interviews with fifty-three experts from across the publishing industry, academia, and foundations with a strong interest in the local news landscape. So as to make a fair assessment of the topic’s placement against a wider news background, we did not limit ourselves just to those with immediate connection to small-market newspapers. From these conversations and our own analysis, seven key themes emerged.

Editor’s note: Download a PDF of this report on Academic Commons. Read Damian Radcliffe’s and Christopher Ali’s sister report, a survey of 400 local journalists, here.

Key Findings:

1 We need to talk about the experience of local newspapers in a more nuanced manner. There is a plurality of experience across the newspaper industry, not to mention across small-market newspapers operating in different towns across the United States. Overgeneralization about the newspaper sector loses important perspectives from smaller outlets.

2. Local newspapers may be in a stronger position than their metro cousins. While local outlets face the same challenges associated with their larger regional and national counterparts, including declining circulations, the migration of advertising to digital platforms, and getting audiences to pay for news, they’ve experienced notable resilience thanks in part to exclusive content not offered elsewhere, the dynamics of ultra-local advertising markets, and an ability to leverage a physical closeness to their audience.

3. Change is coming to smaller papers, but at a slower pace. Attributable to lower audience take-up of digital (in particular among older and more rural demographics) and the continued importance of traditional advertising routes (print, TV, and radio) for local businesses, many local newspapers have enjoyed a longer lead time to prepare for the impact of digital disruption.

4. The consolidation of main street is changing local advertising markets. Although local businesses may be more likely to retain traditional analogue advertising habits, the increasing homogeneity of our consumer experience (manifest, for example, in the rise of Amazon and Walmart) is reshaping local advertising markets. As local businesses are replaced by larger national chains with national advertising budgets, this reduces local newspapers’ advertising pools.

5. Financial survival is dependent on income diversification. The evolution of local advertising markets and, in particular, the consumer retail experience makes it increasingly important that local newspapers continue to explore opportunities to broaden their revenue and income base. Our research found that small-market newspapers are experimenting with multiple means for generating revenue, including paywalls, increasing the cost of print subscriptions, the creation of spin-off media service companies, sponsored content, membership programs, and live events.

6. There is no cookie-cutter model for success in local journalism. Each outlet needs to define the right financial and content mix for itself. This may seem obvious, but during our interviews some editors whose papers are part of larger groups were critical of corporate attempts to create templates—and standardize approaches—that remove opportunities for local flexibility. “What works in one area, won’t necessarily in another,” was a message we heard from multiple interviewees, and a maxim which can be applied to both content- and revenue-related activities.

7. The newspaper industry needs to change the “doom and gloom” narrative that surrounds it. While acknowledging that the future for small-market newspapers will continue to mirror the rockiness of the industry sector at large, our research shows that there is cause for optimism. Sizable audiences continue to buy and value local newspapers. As a result, it is incumbent that the sector begin to change its own narrative. Outlets need to be honest with their audiences about the challenges they face, but they can also do more to highlight their unique successes, continued community impact, and important news value.

Introduction

This report stems from our long-held interest in the health of local news, and the importance of local journalism to communities and the wider information ecosystem. Given the significance of local media in these areas, it is perhaps surprising that this is the first attempt at a national landscape review since the 2011 analysis featured in the FCC’s 468-page omnibus report about the “Information Needs of Communities.”1

Following this seminal but overlooked report, much subsequent discussion has focused on single geographic areas (such as New Jersey) or emerging players (like online hyperlocals) rather than the local sector as a whole. Moreover, with most of the focus on digital players, the experience of traditional outlets, including local newspapers, has been ignored.

During the past decade, the fortunes of the newspaper industry changed dramatically. In 2007, newspapers boasted revenues of approximately 55.6 billion dollars (combined advertising and circulation revenues) and a workforce of 68,160. Two years later, well over one hundred titles had closed, including major publications like the Rocky Mountain News; revenues plummeted by almost twenty billion dollars, hovering around thirty-seven billion dollars; and the workforce fell to 56,230.2 3 4

The sector has never fully recovered. Titles continue to shrink or be shuttered, layoffs are a regular occurrence, and the perennial search to replace print advertising dollars with new sustainable revenue forms continues unabated.

In examining the causes and impact of these dramatic developments, attention from researchers has predominantly focused on large metro and national newspapers, with less attention given to the small-market newspapers that populate and inform many American communities. This study aims to rectify this through a careful study of small-market newspapers, or those weekly or daily print newspapers with a circulation of under 50,000.

Research Context and Literature Review

Why Local Matters: The Three Major Impacts of Local News

Scholars have studied the influence of local newspapers on society for over a century. Beginning with turn-of-the-century academics like Gabriel Tarde in France, research showed how newspapers help form and solidify communities, and crystalize public opinion by provoking conversation.5 Later, researchers from the Chicago School of sociology documented how newspapers help immigrant communities both integrate in, and define themselves against, the American melting pot.6 7

Current research informs us about how newspapers assist in voting decisions, continue to foster community identity and solidarity, and—as is often the case with small-town newspapers—act as community champions.8 As Jock Lauterer writes, these papers (what he calls “community newspapers”) are “relentlessly local” and provide “affirmation of the sense of community, a positive and intimate reflection of the sense of place, and stroke for our us-ness, our extended family-ness and our profound and interlocking connectedness.”9

While digital technologies have certainly impacted these roles and responsibilities, the core mission of local newspapers remains unchanged.10 Based on our review of recent academic research, we identified three key areas where local news and newspapers add clear value to American life, specifically in the areas of democracy, community, and media ecosystems. Understanding this contribution provides useful context for our own research.

1. The value to democracy

First and foremost, newspapers—both large and small—perform an important watchdog role: acting as the public’s eyes and ears against those in power.11 12 Steve Barnett emphasizes their important role in likewise representing communities back to the powers-that-be and campaigning on behalf of the community itself.13

For her part, Penelope Muse Abernathy notes five democratic functions of local newspapers in her book Saving Community Journalism:

- Being the primary source for local, original reporting

- Defining the public agenda

- Encouraging economic growth and commerce

- Fostering a sense of geographic community

- Helping us understand our vote14

This final function on Abernathy’s list is a particularly important relationship—that between voters and newspapers. Studies by Jack McLeod, for instance, identify a relationship between local media consumption and “institutionalized participation”—actions like voting and contacting local officials—concluding “it is clear that communication plays a central role in stimulating and enabling local political participation.”15 16 Lee Shaker’s study of Seattle and Denver, two cities where newspapers had recently stopped printing, echoed these results. Shaker found that both “Seattle and Denver suffered significant negative declines in civic engagement when they lost one of their daily newspapers.”17 The relationship between newspaper reading and civic engagement was again confirmed by Sam Shulhofer-Wohl and Miguel Garrido, who studied the closure of The Cincinnati Post in 2007 and observed a reduction in the competitiveness of elections.18 In helping community members determine their vote, newspapers provide for what is now called the “information needs of communities.” This has been defined as: “those forms of information that are necessary for citizens and community members to live safe and healthy lives; have full access to educational, employment, and business opportunities; and to fully participate in the civic and democratic lives of their communities should they choose.”19

2. Value to the community

Building on the information needs of communities, newspapers also create community and help people feel more attached to where they live.

To do this, they take on numerous roles: informing the community about itself;20 21 performing a ritualistic function as part of readers’ everyday lives22 and providing a sense of comfort to readers and viewers;23 helping communities understand themselves and shape their identities;24 25 setting the standards and norms of the community;26 positioning themselves as the conduit between global events and local conversations;27 28 and transcribing the first record of history for many American communities.29

Acting as a local champion is another way local newspapers help fashion, maintain, and celebrate community solidarity and identity.30. These media outlets not only serve a specific place, but actively help to create it by defining its contours and boundaries.31

Findings show that these community-building and solutions-oriented functions are particularly important and valuable for minority and immigrant communities, both in helping them assimilate to their host country and to stay connected to family and friends abroad.32 33

In performing these roles, small-market newspapers also modify the watchdog function discussed above. Here, community members are often more interested in newspapers’ ability to be a “good neighbor” rather than an attack dog.34 35

To do so, small-market newspapers often focus on solutions rather than just identify problems. This departs from traditional concepts of objectivity in American journalism, bringing it more in line with the tenets of public journalism and civic journalism.36 Today, these characteristics are increasingly reflected through the lens of “solutions journalism.”37

3. Value to media ecosystems

Newspapers remain an integral part of the local media ecosystem. Indeed, they are often the only news voice in a community.38 Even when they’re not, they still perform the bulk of original reporting. In his 2009 book, Losing the News, Alex Jones asserts that newspapers account for eighty-five percent of all accountability news within a media ecosystem.39

Unfortunately, Jones does not provide an explanation for how he came to this figure. A 2010 study by the Pew Research Center on Baltimore, however, did discover that newspapers accounted for nearly half (forty-eight percent) of the original reporting in the city during the time period covered.40 Taken at face value, this suggests that the bulk of stories covered by television and cable news find their origins in newspaper reporting.

Nevertheless, we cannot discount the fact that the prominence of newspapers as a media source for consumers has declined as readers gravitate toward a plethora of other sources.

This led Nielsen to argue that even though newspapers may have lost their status as “mainstream media,” they nonetheless serve as “keystone media” by existing as “the primary providers of a specific and important kind of information and enable other media’s coverage.” Their ongoing decline has severe “ecological consequences that reach well beyond their own audience.”41

By the Numbers: Essential Data on the Newspaper Industry, 2007-2016

The newspaper industry’s vital statistics over the past decade do not make for pretty reading. As demonstrated by Pew’s annual “State of the News Media” reports and other studies, the sector has faced many challenges during the last ten years in terms of general revenue, circulation, and employment.

In its 2017 report, Pew described an industry in decline, with subscriptions retreating eight percent from 2015, and advertising revenue dropping ten percent to around eighteen billion dollars (plus eleven billion dollars from circulation). There has also been a notable reduction in newsroom employees, with a four percent reduction since 2014 and a thirty-seven percent reduction since 2004 to now account for 41,400 people.

State of the News Media Industry: Key Statistics

| Year | Advertising | Circulation | Newsroom |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2007 | -7.30% | -2.30% | -0.65% |

| 2008 | -14.90% | -0.60% | -3.58% |

| 2009 | -26.60% | -0.20% | -14.4% |

| 2010 | -6.60% | -2.40% | -8.6% |

| 2011 | -7.00% | -0.90% | -2.22% |

| 2012 | -5.90% | 5.00% | -4.99% |

| 2013 | -6.80% | 1.80% | -4.8% |

| 2014 | -6.40% | 1.00% | -5.0% |

| 2015 | -7.80% | 1.20% | -4.1% |

Source: Pew Research Center 42

What about local?

These numbers—reporting on revenues, circulation, and employment—while valuable, do not tell the entire story. A major challenge for anyone trying to make sense of this data is its aggregated nature, which makes it difficult to deduce trends at a more granular level.

More specifically, what do we know about changes at small newspapers versus major metros, national newspapers versus metros, and weeklies versus small dailies? The answer, based on available and published data, is not very much.

The missing middle: small-market newspapers in the United States

There are currently 7,071 newspapers (daily or weekly) in the United States according to Editor & Publisher. Of those, 6,851 have circulations under 50,000.

This means that upwards of ninety-seven percent of newspapers in the United States can be categorized as “small-market.” Of the weeklies in particular, most, if not all, have a circulation under 30,000.

Using Editor & Publisher’s data, we have endeavored to provide granular information on the types of small-market newspapers that exist in the United States.

Daily Small-Market Newspapers by Circulation

| Circulation | Number of newspapers |

|---|---|

| 25,001–50,000 | 139 |

| 10,001–25,000 | 366 |

| 5,001–10,000 | 396 |

| 5,000 or less | 301 |

| Total small-market dailies | 1,202 |

Source: Editor & Publisher

Weekly Small-Market Newspapers by Circulation

| Circulation | Number of newspapers |

|---|---|

| 35,001–50,000 | 99 |

| 20,001–35,000 | 368 |

| 10,001–20,000 | 758 |

| 5,001–10,000 | 1,084 |

| 1.001–5,000 | 2,843 |

| 1,000 or less | 497 |

| Total small-market community weeklies | 5,649 |

Source: Editor & Publisher

Implications

Three things become clear from these datasets:

The vast majority of newspapers in the country have small circulations of under 50,000. Yet they seldom get much attention from researchers.

There is a tremendous amount of diversity in the size and scale of publications that are considered “small-market.” With a threshold of 50,000, this includes everything from The Chariho Times (Rhode Island, circulation 637) to Newport News’s Daily Press (Virginia, circulation 48,828). This variability cannot possibly be appreciated when circulation numbers and revenues are consolidated into a generic “newspaper industry” category.

We need a regular detailed census of local newspapers, split into different sub-markets, to understand and map a more holistic picture of the U.S. newspaper industry. Unfortunately, many existing surveys are being rolled back,43 meaning that our knowledge of this space will diminish unless others step in.44

The data and the three clear conclusions which derive from it suggest that small-market newspapers represent “a silent majority”: a major cohort that we as a community of researchers know very little about and a community of practitioners that too often—we were told—knows little about itself.

These conclusions also underscore our point that when telling the story of the newspaper industry in the United States we need to show more nuance and specificity, rather than aggregated numbers. While consolidated data has its place, it should be accompanied by sub-sector analysis, which allows us to more effectively understand the diversity of this sector.

Our study seeks to help redress this recent imbalance. We embarked on our research with a relatively simple yet ambitious question: How are small-market newspapers responding to digital disruption?

From the data collected from our research, we also strove to report on the future of small-market newspapers by asking: How can small-market newspapers best prepare for the future?

Through in-depth interviews, secondary research, and an online survey of local journalists, we began to address these all-important questions.

Methodology

Definitions: What Is a Small-Market Newspaper?

The focus of this study is small-market newspapers. There is no agreed-upon definition of what constitutes a “small,” “medium,” or “large” newspaper. For the purposes of our research we have chosen to define a small-market newspaper as a daily or weekly print publication with a circulation of under 50,000.

This is consistent with the literature on community newspapers and community journalism, the most closely related academic fields.45 It also allows us to exclude the major national and metro newspapers, and the emerging cadre of online hyperlocal news sites, as both of these platforms have received substantial and comprehensive coverage from researchers of late (see the Knight-Temple Table Stakes Project and the Free Press’s New Voices: New Jersey project).46

Methods

To answer our research questions, we drew upon an established research method in the social sciences: in-depth interviews. Given the deliberate broadness of our research question, the goal was to be exploratory, approaching as many respondents as possible to get a variety of perspectives from stakeholders with an interest—and informed perspective—on our research topic. To this end, we did not limit ourselves just to those with immediate connection to small-market newspapers. Instead, to ensure that we benefited from a wider overview of the local news landscape, we interviewed experts and practitioners from across the industry. This also allowed us to place our findings in conversation with the other discussions about the health of the newspaper and local news industries. Despite our desire not to limit ourselves, the majority of our respondents had experience at small-market newspapers.

In total, we conducted fifty-three in-depth interviews. Positions of our respondents included: Small-market newspaper editors, publishers, journalists, and owners (n=12) Metro newspaper editors (n=10) Executives at major newspaper chains (n=5) Editors, publishers, reporters at hyperlocal online news organizations (n=4) Researchers, think tanks, funders, foundations (n=13) Policymakers, industry watchers, advertisers, and associations (n=9)

Each interview lasted between thirty minutes and two hours. They were non-directive, open, and semi-structured in nature. Although an interview protocol was drafted and used, we did not stick rigidly to it. Instead, interviews had a more conversational tone, flowing—when possible—naturally between our points of interest. If key topics did not emerge organically, they were introduced by the interviewer.

Our initial list of respondents was compiled by using existing contacts and knowledge of the field. Thereafter, a snowball method was used to locate and recruit more respondents. Interviews continued to be solicited until such point as saturation (i.e., no new knowledge) was achieved.

Professional transcription services were used to transcribe the interviews.

Using a method known in the social sciences as grounded theory,47 we conducted close readings of the transcripts and began to assemble categories and themes. These themes were then refined through comparison and combination. This culminated in the structure and themes in this study.

In the end, we developed three overarching themes (revenue and business models, changing journalistic practice, and evolving philosophies of journalism) that we share below.

From these themes, we have also created a list of recommendations for researchers and practitioners alike. The aim, of course, was not and is not to create a static list of best practices, but rather to begin a conversation about small-market newspapers—their present and future, challenges and opportunities.

Why This Report Matters

Our research is the first attempt to provide a national lens on local media (and in this instance, we are looking solely at the experience of small-market, local newspapers) since the Federal Communication Commission’s 2011’s report “The Information Needs of Communities” (the “Waldman Report”).48 A summary of important papers published since that time is included in the Further Reading chapter of this report.

In its 2011 study, the FCC conducted an omnibus study of local media ecosystems, focusing specifically on the information needs necessary for American communities and American democracy. Considerable attention was paid to the newspaper industry, in particular small-market newspapers. With the exception of the Pew Research Center’s annual “State of the News Media” reports, this was the last time that researchers paid such attention to small-market newspapers, or indeed the newspaper industry in its entirety.

The media world has changed substantially in the years following the Waldman Report in 2011. Newspaper chains have merged, creating the behemoths of the industry: New Media/Gatehouse (432 newspapers), Gannett (258 newspapers), and Digital First Media (208 newspapers). Social media’s impact has grown, further fracturing audience attention and advertising dollars. These changes have encouraged newspapers to accelerate their digital presence and experiment with digital tools such as paywalls, partnerships with—and against—Facebook and Google,49 and integrate new digital metrics into the workplace.

This study enables us to take stock of how local newspapers are responding to these developments and ongoing digital disruption.

Alongside discussing the impact of these major changes, our interviewees also revealed an industry keen to tell its own story and to hear about the perspectives of others. One reason for this desire is that, until recently, this has been an underreported sector and one that needs to hear its own story reported back and analyzed.

Although there has been lots of great work in this space, the majority of efforts have focused on either a defined geographic area such as New Jersey 50 or specific verticals such as media deserts 51 and online hyperlocal media. 52 The experience of local newspapers, especially from a cross-country perspective, has tended to be overlooked.

A number of developments in the past six months have begun to address this. We note, for example, a weekly newsletter on local matters published by Poynter, the excellent case studies/how-to guides from the Local News Lab,53 The Local Fix,54 and the Columbia Journalism Review.55 Our study sits alongside these efforts as part of a revitalized discussion about the health and future of local journalism in the United States.

Embracing the methodology of oral history research, our interviewees told us not just what local journalism leaders are doing, but what they want to do and what they believe they are doing.56 This approach allowed us to see local journalists as a social group, telling their stories and that of the local media landscape as they see it in 2016–17.

Combining these insights with our own analysis and expertise, we hope this report will make a significant contribution to the discussion about the state of small-market newspapers in the United States, and their continued importance to communities and the wider news and information ecosystem.

How Are Small-Market Newspapers Responding to Digital Disruption?

In this section we outline some of the key themes to emerge from our interviews with industry practitioners and experts, as we address how small-market newspapers are adapting to the constantly changing media landscape in which they operate.

This analysis is especially important, given that there has been no wholescale exploration of this topic since the Waldman Report in 2011. Yet, as we have noted, the media landscape has changed considerably, as revenue and consumption models have rapidly evolved. For better or worse, the last two decades have brought about a period of digital disruption for local newspapers. By this, we mean that newspapers have been forced to adapt to the now-ubiquity of digital technology in our everyday lives. This has changed reporting practices, information flows, audience reading habits, business plans, revenue streams, distribution mechanisms, and competition.57 58

In talking about digital disruption we don’t attribute negative or positive connotations to this term, but rather recognize that there has been a seismic change within the industry over the past decade, a segment of which—small-market newspapers—has been under-examined.59 60 Small-market newspapers are having to address, on multiple fronts, core questions related to their business and content: this includes reexamining their structures and income models, as well as changing the nature of what they do and how they do it.

It’s this story, which touches on business and revenue models, as well as the practice and philosophies of journalism at local newspapers that we explore in the first part of this report.

Business and Revenue Models

Arguably the two most important issues facing small-market newspapers are their revenue model and the business structure which supports it. There is considerable diversity in this space. Small-market newspapers, for example, encompass everything from “mom-and-pop” weeklies to daily products from large groups such as Gannett and Hearst.

Despite this diversity, all outlets—large and small—are grappling with many of the same issues. In particular, that means how to ensure their financial survival and future prosperity. Income diversification is fundamental to this, even if the long-term potential of some ideas are, at present, unproven.

Our research identified a number of ways in which small-market newspapers are seeking to diversify their income streams and secure their futures. Publications will have to determine which of these options might work best for them, accepting that what works for one title in one market might not work for a similar paper in a different environment.

We hope, nonetheless, that these ideas and case studies can provide valuable inspiration and reaffirmation for newsrooms embarking on this journey.

Context: the revenue challenge

Business and revenue models often get conflated, but for the purposes of this report we delineate between the two by separately analyzing the income streams flowing into a newspaper (the revenue model) from some of the larger structural questions (the business model) small-market newspapers are addressing.

As Josh Stearns of the Democracy Fund reminded us, “A revenue model is not a business model and to get [an] actual, sustainable business model you have to figure out which of these [revenue models] work given your capacity and your community needs.”

Across the industry, print revenues continue to dominate the income ledger, accounting for seventy-five to eighty percent of income at most small-market newspapers, just as they do at larger outlets.61

This is potentially problematic in the long-run, given the impact of changes to local advertising, which are reducing the revenue pool that local newspapers can draw on. As Kevin Anderson observed, as retail moved from local to regional to national, so too did advertising: “Looking back at old editions (of the Sheboygan Press in 2015), it’s not just the volume of the ads that’s striking, but also the variety—the number of local businesses that used to advertise with us . . . hundreds of small, local businesses that would have advertised with my newspapers simply no longer exist.”62

Because of this, it is incumbent on small-market newspapers to broaden their revenue base, and to reduce this dependency on traditional income streams. Our research found that publishers are very aware of this need, but also recognize that this transition cannot be achieved overnight.

Seven Popular Revenue-Raising Practices

Against a backdrop of the continued reliance on print dollars for most small-market newspapers, and the challenge of attracting sufficient local advertising, this section explores some of the ways in which small-market newspapers are looking to expand and diversify their income base.

It’s not easy, but fortunately, good ideas are plentiful: there are a plethora of case studies showcasing different ways in which local newspapers can generate income.63 64 Below we outline some of the more popular and practical options being explored by publishers.

1. Subscriptions and single-copy sales

Alongside traditional display advertising subscriptions(online and in print), single-copy sales and paywalls continue to be popular income sources at small-market newspapers.

Many smaller titles, particularly weeklies, remain heavily dependent on single-copy sales. Al Cross, director of the Institute for Rural Journalism and Community Issues, told us, “People are making the buying decision every single week, plunking down fifty cents, or seventy-five cents, or even a dollar for that paper.”

Without the certainty of subscription income, many smaller papers are “vulnerable,” Cross argued, and understandably wary of rocking the readership boat. While this type of risk aversion is not unique to these kinds of weekly outlets, these titles may have less wiggle room than those with a larger circulation base. The type of papers that Cross describes have an average weekly circulation of around 4,000.

At many daily newspapers circulations are higher, which may offer a slightly larger margin for error in terms of the opportunity to experiment. Nevertheless, as many interviewees told us, they are still potentially hamstrung by a number of other strategic considerations. Several editors identified issues such as the fact that their print subscribers tend to be older and resistant to change, while others highlighted the discrepancy between the size of their digital and print subscriber bases (sometimes digital is around ten percent, or less, of the print audience). These factors can impact on the scope for maneuverability and innovation.

Yet change is often necessary, not least because of shrinking newsrooms and the need to create content for an increasing number of platforms. This means that the newspaper of today cannot afford to look like the newspaper of yesterday.

As Robert York of tronc explained:

If you want to do new things, you have to stop doing old things that don’t work. And I think that’s something in our industry [that] is very difficult to do because everything has a constituency of at least one.

So, if you take a comic out of the newspaper, somebody likes that comic, and they will call and complain and cancel their subscription. If you take a box of ten mutual funds that you always run, and take that out of the paper, off to online, once again, somebody will call and complain because that was their mutual fund.

2. Paywalls and digital subscriptions

The predominance of paywalls, often present at even the smallest small-market titles, is a more recent phenomenon than is generally recognized. In 2012, Gannett, Lee Enterprises, and McClatchy all announced plans to introduce paywalls for some—or the majority—of their titles65 66 67 with Scripps following suit later that year,68 before Digital First Media in 2013.69 70

Since then, in just a short period of five to six years, paywalls have rapidly become an established means for newspapers to generate income from readers.71 This doesn’t mean, however, that paywalls aren’t necessarily a source of potential tension for newsrooms and audiences alike.

In an era where journalists are frequently rewarded for page views, anything which creates a barrier to readership can be a source of friction. Meanwhile, for audiences accustomed to free, unmetered access to content for much of the early internet age, the move to paywalls marks a major shift in their online relationships.

From an audience perspective, research from Alex T. Williams for the American Press Institute72 found that larger newspapers were often good at communicating to readers how and why paywalls were being introduced.73 But that dialogue often ceased post-launch. New visitors may be therefore unclear about paywall structures and the need for them.

Journalists can play a direct role in contributing to this conversation. Lauren Gustus, at the time the executive editor of the Coloradoan in Fort Collins observed how her reporters will often share details on social media of special subscription offers, telling their followers: “I’m proud of the work I do . . . Here’s the link if you wanna subscribe.”

Gustus contends that, alongside this, her journalists don’t simply leave these matters to the sales guys. “Anyone in our newsroom could tell you about the demographics of our subscribers,” she said. “They could tell you how many subscribers we have and they could tell you how much it costs to subscribe to the Coloradoan for print or digital.”

The paper has one of the highest digital-only subscriber bases across the Gannett group, with paid circulation up year-on-year for the past two years. Whether this can be attributed to the continued communication between the newsroom and the paper’s audience cannot be proven, but it remains, nonetheless, a model that others can potentially learn from.

Our research also found clear evidence that paywalls and digital subscription models are not set in stone. There are plenty of opportunities to experiment with them. The Dallas Morning News, for example, has deployed three different paywalls over the years, from a hard paywall,74 and later 75 a mixed premium76 versus free site, to a metered model.77 The current paywall also distinguishes between in-market and out-of-market audiences.

For titles like The Dallas Morning News, some sections of the site (e.g., entertainment) don’t count toward the meter, as the content is well supported by ads. Other outlets, but not all, take a similar approach to popular verticals such as job boards and “what’s on” listings.

It’s clear from our research that not only are paywalls newer than we might realize, but they’re also a space that is far from static.

3. Events

Of the new, emerging sources of revenue that newspapers are engaging in, the events space may be one of the most promising. Aside from their potential as a means for story gathering and community engagement, events also offer opportunities for sponsorship, ticket sales, and other income streams.

One digital site, Billy Penn in Philadelphia, has made events a cornerstone of its business model.78 As founder Jim Brady told us, “I’ve said a bunch of times, and I’m dead serious about it, that part of what makes it—people say, ‘What’s your business model?’ It’s like, ‘Events and low overhead.’ ”

For many other digital operators, such as those tracked by Michele McLellan as part of her database of promising online local news startups, Michele’s List,79 events are described as an effective means to engage with their community, even though for most outlets they account for less than twenty percent of revenue.

This percentage may grow in the future, but it also alludes to another benefit from events: their ability to provide opportunities for face-to-face engagement and interaction with readers and non-readers alike.80

MinnPost, a nonprofit serving the Twin Cities in Minneapolis, for example, uses events to deepen relationships with existing supporters by offering members free and discounted tickets.81 Others such as The Seattle Times have worked with external partners to bring non-subscribing audiences to their education events.82 Meanwhile, as far back as 2013 the Chattanooga Times Free Press (circulation 75,336) was producing twelve large events a year, generating seven-figure income levels, eleven percent of its retail revenue, in the process.83

Tom Slaughter, executive director of the Inland Press Association, was one interviewee who felt that events were likely to be part of the “portfolio of businesses” required to “support the infrastructure of what we call a daily newspaper.” After all, he reflected, “Newspapers will not be able to sustain themselves solely on digital advertising.”

4. Media services

One clear way that a number of publishers are expanding revenue sources is by creating, or buying, spin-off businesses which capitalize on their editorial and design expertise. Income from these services, which includes building apps and websites for small and medium-sized businesses, can then be poured back into resourcing the core product.

In doing this, small-market newspapers are not just leveraging the skills they have developed, but also the trust and heritage associated with their brand.

As Steven Waldman, author of 2011’s FCC report on “The Information Needs of Communities” argued:

Those brands and that reputation means something and that’s partly why I think these service businesses really do have some potential. I think when you’re a small business and you’re getting calls from five different people claiming to be able to help you with your website, and you have never heard of four of them and one of them is the local newspaper, I think you may get the local newspaper [to help you].

Other newspapers such as the Oregon-based RG Media Group and EO Media Group are leveraging different areas of expertise and resources, offering commercial print operations, which includes printing the publications of their neighbors.84 The Columbian in Vancouver, Washington, prints The Oregonian, which is based in nearby Portland, and The Register-Guard in Eugene publishes the Gannett paper for Salem, the Statesman Journal.

Given these transferable skills, it’s perhaps no surprise that we’re seeing small—and large—newspapers across the country branching out into the media services space. This is another trend we can confidently expect to continue.

5. Newsletters

On a smaller scale, the humble newsletter is back and in vogue with sales teams and audiences alike. “As the digital ecology evolves, it sometimes pays to go back to basics and adapt relatively old ideas for new times,” noted London School of Economics’ Charlie Beckett in his introduction to a 2016 report, “Back to the Future—Email Newsletters as a Digital Channel for Journalism” by Swedish journalist Charlotte Fagerlund.85

The revenue opportunities in this space include sponsorship for specific newsletters covering key verticals such as politics, sports, the environment, or education, as well as the opportunity to embed advertising as hyperlinked text or display ads.

With analytics offering user insights such as clickthroughs and open rates, it’s relatively easy to calculate an ROI, too. Although as Digiday has pointed out, this is not without its challenges.86 “E-newsletters are limited in their ability to monetize because of the lack of a third-party auditor and the constraints of third-party platforms,” argued a recent article,87 not least because if emails are forwarded, then third-party tools don’t count these as new opens.

This is clearly an issue, but irrespective of this newsletters remain88 a source of investment for small-market newspapers, and a potential tool for valuable revenue and consumer data.

Rob Barrett, president of digital media for Hearst Newspapers, stressed the role that newsletters can play in creating a “daily habit” with readers, which is particularly important at a time when the daily habit of reading a newspaper may be on the wane.

Meanwhile, Lee Rainie at the Pew Research Center highlighted the power of using newsletters to offer a “foot in the door” to your website and other content. From these lower-level engagements, deeper relationships may flourish.

Perhaps with this in mind, Barrett posited that newsletters are about more than just delivering content (and ads); they should also be considered part of a newspaper’s customer relationship management (CRM) efforts, given the potentially valuable information that newsletter subscribers share on sign-up and through their consumption.

He explained, “I wouldn’t say, ‘Hey, we’re investing in newsletters.’ We’re investing in customer retention, customer relationship management, and it’s very clear that using sort of the best email technology to generate it, to target, to personalize it, and to have the database of customers, and that having the best technology investment is a very, very big deal.”

Given these factors, newsletters are an area of investment—and one with a potentially positive financial return—that we expect to see a further focus on.

6. Obituaries

As we noted in our discussion about digital subscriptions, publishers aren’t necessarily blocking access to all of their content. Obituaries are one area where we see different approaches being used.

The Bulletin, a daily newspaper in Bend, Oregon, excludes obituaries—alongside classified ads, job openings, its events calendar, and restaurant and golf guides—from its thirteen-dollar-a-month paywall. In contrast, the Calhoun County Journal, a weekly in Bruce, Mississippi, places obituaries, along with other popular content such as recipes, behind a paywall accessible via a WordPress login.

One possible reason for this divergence is the different attitude that some small-market newspapers adopt when producing this content. As Waldman told us, the cost for publishing obituaries can range from hundreds to sometimes thousands of dollars. But not everyone is comfortable with that approach. He said:

There’s still a couple newspapers out there that do it for free. They [see] this is a service to our community and we’re not gonna charge for it. I think those are very few and far between, but I have come across some like that, and some have kept their prices down in the forty–fifty-dollar range, something like that. But, certainly in the metro papers, the rates are going way up.

As publishers seek new revenue streams, some of them are turning to obituaries as a potential means to attract different sources of revenue. The Courier Record of Blackstone, Virginia, is one such paper which has made this journey. As owner Billy Coleburn reflected, “We used to never charge for obits, then we charged for some versions and didn’t charge for others. Now, basically most obits in our paper are paid. Do a color photo, and it’s not a bad additional piece of revenue.” At the same time, Coleburn readily conceded that “obits are a very important part of record of the paper, no doubt, [and a] record of the community.”

This wider value helps explain why some small-market newspapers wrestle with where obituaries sit on the revenue versus information continuum. Many local journalists, perhaps, underestimate the importance of this content to members of their community and individual readers. But Waldman reminded us, “The most important news event in most people’s lives is not the Iowa Caucus, it’s the birth of their child or the death of your parent.”

Leveraging this may seem rather cynical to some, but as Waldman argued, “If the newspaper can be a part of actually helping that person, you’re gonna be connecting with them on a much more powerful level, being much more useful than you’ve ever been.”

7. Foundations, crowdfunding, and other emerging ideas

Finally, in this section we highlight some of the other revenue-raising ideas being explored by our interviewees and others across the industry. This list is by no means exhaustive, but instead seeks to highlight some of the various ways in which small-market newspapers across the United States are looking at different revenue sources to help underpin their journalistic endeavors.

Foundations are, perhaps, the most obvious example of this. In many cases their support has enabled news organizations to experiment and do new things. This has included new forms of journalistic activity,89 support for specific beats such as Education Lab at The Seattle Times90 and state reporting by the Center for Public Integrity,91 exploration of new revenue models,92 and relationship-building.93

Of course not every publisher is able to benefit from the foundation support. In particular, we note that the pool of outlets that has benefited from this is small, relative to the size of the sector, and that the focus is often restricted to tech and innovation. However, there’s no doubt that this income source is valuable for those that have benefited from it. We expect to see more publishers seeking to tap into this potential revenue stream.

Another reasonably established form of fundraising is crowdfunding,94 which has been used to cover specific stories and beats such as The Texas Tribune’s series “Undrinkable,” “The Shale Life,” “The Ticket,” and “Bordering on Insecurity,”95 as well as its recruitment of a community reporter in late 2016.96

Another long-established means for attracting additional revenue is the use of consumer questionnaires by local news outlets such as the Herald and News (Klamath Falls, Oregon) and The News Journal and DelawareOnline.com (Wilmington, Delaware).

Though this isn’t necessarily a new idea (Nieman Lab wrote about an early iteration in 201197) it offers publishers an opportunity for alternative forms of monetization, with publishers being paid by Google for each completed Google Consumer Surveys (GCS).98

Pop-Up Consumer Survey from the Herald and News (Oregon)

Source: Herald and News 99

Meanwhile, the Blue Mountain Eagle in John Day, Oregon, the oldest weekly community newspaper in the state, launched in 1868,100 enables its audience to purchase popular images (see below).101

Source: Blue Mountain Eagle 102

Readers can repurpose images for everything from a four-by-six print ($3.99) through to mugs, mouse mats, t-shirts, and large canvas prints (twenty-four-by-thirty-six mounted, $143.50).103

This additional revenue stream sits alongside traditional advertising and metered access to its content (unlimited access to the website costs forty dollars per year).104

It’s likely this isn’t a large money-spinner for the publication, but setting up an online store in this way may be a relatively simple method for generating some additional revenue with minimal effort.

Other outlets are also exploring opportunities around eCommerce, ranging from mounted front pages of The Denver Post105 to keepsake pages and coffee-table books from The Seattle Times.106

For some outlets, harnessing their unique local archive in this manner may be a revenue area to watch.

Final thoughts on revenue matters

These examples, as well as initiatives such as membership schemes, sponsored content, and other ideas, give us a sense of how newspapers are experimenting with different opportunities to generate income. There’s no magic combination for making this work, but what this section shows is that there are no shortage of potential routes to revenue.

Changing Journalistic Practice

A fundamental reason why publishers need to experiment with different opportunities for income generation is because the traditional funding model for news is broken. Technology is rapidly changing the way content is created, distributed, consumed, and monetized.107

This is all happening at such a pace that it’s easy to forget that many popular digital platforms and online behaviors are, in fact, relatively recent additions to media diets.108

In the space of a few short years, new storytelling tools like Facebook Live, Periscope, and Snapchat have quickly become part of the journalist’s toolkit, while usage of more established platforms like Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram has evolved as their functionality and audience continues to grow.109 110 111 Meanwhile, platforms like Vine, Meerkat, and Google+ have either closed or effectively been consigned to the digital graveyard.112 113

These developments have required news and media outlets to move with the audience, embracing new platforms and finding new ways to tell stories.

In this section we explore some of the ways that local newspapers are engaging with these channels, highlighting examples of practice and some of the strategic implications and challenges which many small-market newspapers are trying to make sense of.

Social media as standard (but it’s an often uneasy relationship)

For some, such as Levi Pulkkinen at Seattlepi.com, the emergence of newer and more established digital platforms can be a cause for optimism. “It’s a really exciting time for journalism,” he said, “because if you run a small newspaper, your potential audience for the stuff you’re doing has gotten gigantic in the last decade.”

The influence of these channels on our media habits is such, Pulkkinen argued, that if you’re not active on these platforms “you’re basically deciding not to play.”

There’s certainly an element of truth to that. But it’s also true to say that some local publishers are deliberately deciding not to play. This is particularly true of many smaller outlets, where resource constraints make it difficult to do everything, and be everywhere.

Moreover, for many of these titles, a reliance on physical newspaper sales means that some publishers are being careful not to cannibalize their print audience by giving away the crown jewels (for free) on social, or indeed anywhere else online. These titles still need people to buy their paper each week if they are to survive.

The Calhoun County Journal of Bruce, Mississippi (population 1,939)114 is a good example of this. With a circulation of a little over 5,000 a week, it’s the only newspaper in Calhoun County. Although active on social media, the paper purposefully eschews Facebook (although not the Facebook-owned Instagram115).

Publisher Joel McNeece, a past president of the Mississippi Press Association who sits on the National Newspaper Association Board of Directors, explained that too many small publishers “think they can stick something on Facebook and that equates to a good advertisement because thirty people liked it. It’s not generating any business for you,” he said, arguing that “your best dollar is still in print.”

For others, the challenges of this relationship go beyond just revenue. Billy Coleburn from Richmond’s Courier-Record (Virginia) was just one publisher who stressed the impact of the new digital gatekeepers on both revenues and audience time, saying, “I view my number one competitor really as Facebook and social media because you’re competing for the hearts, and minds, and the attention span of human beings. And our attention span is ridiculously small these days.”

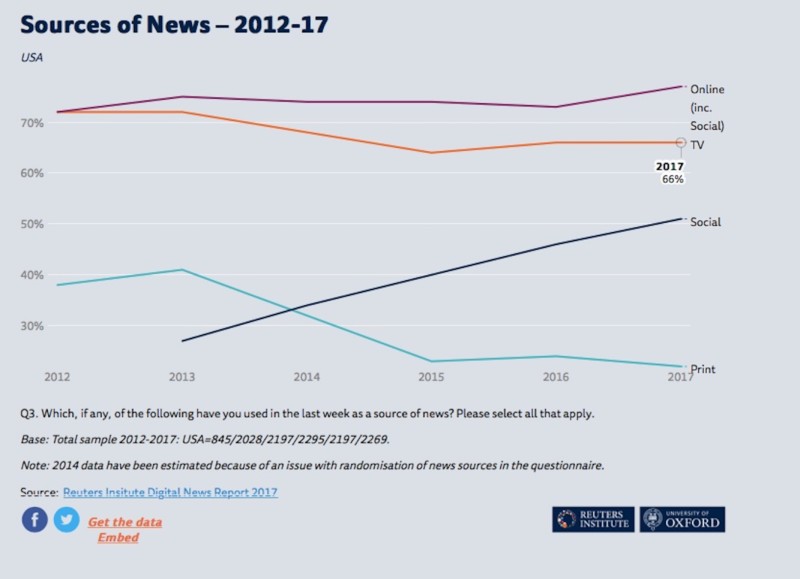

Despite these challenges, the popularity of social networks as a news source means that it takes a bold publisher to purposefully refrain from using these channels. Data from the “Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2017” found that fifty-one percent of digital news consumers in the United States now get news from social media, a cohort that’s grown five percent since 2016 and doubled since 2013.116

During this same period (not long after the Waldman Report was published), print as a source for news fell precipitously. Reports from Pew have consistently told a similar story, especially among younger audiences.117118

Source: Reuters Institute/Oxford University 119

The growth of video and live video reporting

At the end of 2016 we undertook an online survey completed by 420 journalists based at small-market newspapers across the United States.120 Our research identified a cohort that is enthusiastically embracing digital storytelling, especially video and live video.121 Newsrooms are benefitting from the low barriers of entry created by smartphones and cheap (and sometimes free) editing tools, as well as new live video streaming services.

However, despite this engagement, publishers face a number of important strategic issues in this space. One key consideration is skills and training, as identified by our survey, which revealed that most journalists tend to be self-taught with new technologies, or they learn from articles on sites like Nieman Lab, Poynter, and MediaShift.

Audiences may need support and training, too, and publishers can play a role in providing compelling content which drives audiences to digital platforms, while at the same time explaining how to use/access these platforms. In doing so, news organizations can play a key role in helping to develop these types of media literacy and digital behaviors.

These platforms may be less effective for some small-market newspapers. Access issues are an important consideration, especially in rural communities where availability may be more limited. Slower-fixed and mobile broadband speeds mean that video, as well as other rich multimedia content, is not necessarily viable for non-urban publishers or audiences.

Finally, a number of interviewees also identified the unproven business and revenue models from many of these platforms as issues. As Amalie Nash, the Des Moines Register’s executive editor and vice president for news and engagement at the time of interview and now Gannett’s executive editor for the West Region, explained: “You look at something like Facebook native videos, which we all agree that’s great for brand, that’s great for getting yourself out there, and this and that, but at the end of the day, you’re making pennies on the dollar in terms of what those videos are providing as far as revenue sources.”

On other platforms, revenue may be even less. A cursory glance at the YouTube channels for many small-market newspapers, for example, shows video views often total between a few thousand and a few hundred.

“Getting five or six or seven hundred views on a single video isn’t a sellable item to an advertiser,” warned Lou Brancaccio, emeritus editor of The Columbian of Vancouver, Washington. As a result, he suggested this may not be a viable medium for smaller outlets to continue investing in so heavily. “The jury is still out on whether or not that is going to pull more viewers onto our website,” he said.

In contrast, given the need for scale and reach, video may be a format that is far more successful for larger newspapers, where views are greater and thus the opportunity for advertising or sponsorship may be more discernible. It will be interesting to see how this dynamic shapes up as the video market continues to mature.

The emerging importance—and influence—of metrics

“Metrics inspire a range of strong feelings in journalists, such as excitement, anxiety, self-doubt, triumph, competition, and demoralization,” wrote Tow Fellow Caitlin Petre in her 2015 report “Traffic Factories: Metrics at Chartbeat, Gawker Media, and The New York Times.”122

Petre observed how “metrics exert a powerful influence over journalists’ emotions and morale,” and that, for all of the positives which these tools can unlock, “traffic-based rankings can drown out other forms of evaluation.” This trend is now beginning to permeate the different tiers of local journalism.

One potential benefit of these tools, suggested Lauren Gustus, the former executive editor of the Coloradoan (Fort Collins, Colorado), is that it enables journalists and editors to quantify readership in a manner not previously possible. The conclusions can sometimes be surprising. “If you look at the metrics, you know that so much of what we do doesn’t get consumed in a way that maybe we think it does,” she said.

The impact of this can be used to realign and reframe certain types of stories, providing evidence (which is especially valuable in a climate of reduced resources) for dropping or diminishing certain beats, while also enabling newspapers to double-down on topics which really resonate with their communities.

Liz Worthington, content strategy program manager at the American Press Institute (API) who leads the Metrics For News program, argued that these types of insights can help to deepen relationships between audiences and small-market newspapers:

By focusing on a few key topic areas, you create more loyalty. The readers really respond to it . . . And the newsrooms we work with are pretty transparent with their audience about why are we doing this and why you are taking this survey to help us figure out what we should do differently. It does lead to higher page views, but also less churn, more loyalty, and hopefully deeper engagement with your audiences.

Editors at papers ranging from the Herald and News in Klamath Falls, Oregon, to The Dallas Morning News in Texas told us that they had benefitted from this approach. Others highlighted some of the cultural challenges presented by metrics, not least when they proffer conclusions that newsrooms don’t necessarily want to hear.

“I think there’s a hesitancy in the newspaper industry among reporters not to recognize what the metrics are telling us,” said Levi Pulkkinen at Seattlepi.com, namely “that we need to change the content.” Specifically, he added, “What we’re finding is that readers have very little taste for incremental coverage, and that’s the bread and butter of local newspaper[s].”

Metric-informed practices can help to achieve these ambitions, and their influence can be seen at some small-market newspapers. However, they may well encounter resistance from those wary of changes to the traditional culture and practice of journalism, and the risk that metrics can have a potentially overt influence on an outlets content mix.123

“Feeding the goat”124

Many of our interviewees come from smaller weekly publications. Journalistic practice in these environs can be very different than metros or newspapers in larger, more competitive news markets. Arguably one of the biggest differences is in the speed of publication and audience expectations around the availability of news content.

For some publishers, being weekly is an editorial asset, enabling them to take a step back and report the news differently from those caught up in the cycle of daily publishing and around-the-clock updates on social media.

But the weekly publishing schedule, while identified as a strength, can also potentially leave outlets vulnerable. Al Cross, director of the Institute for Rural Journalism and Community Issues, explained how the News-Democrat & Leader—a bi-weekly paper in Russellville, Kentucky (population 7,037)—risked being left behind as audiences migrate to The Logan Journal, “an online newspaper,” its Twitter bio notes, “that is devoted to bring you the stories quicker and better.”125

For daily papers, different challenges abound. Lou Brancaccio, emeritus editor of The Columbian, a seven-day-a-week publication in Vancouver, Washington, described a fast-moving environment where publishers can’t afford to be late to a story. “The worst thing that can happen to a newspaper is that somebody reads some news from their Facebook friend, they go to The Columbian website to see if we have it, and we don’t have it,” he said.

In many cases, Brancaccio argued, the paper does have the story, but the reporter is waiting until it is complete before publishing. “That’s old-school thinking,” he said, leading him—and others—to encourage reporters to publish online when a story breaks, fleshing it out as further details emerge.

For many journalists that’s a radically different approach from the way they have previously worked. But Brancaccio believes it’s necessary for many outlets in this day and age. “The odds are somebody else has it,” he said, “and if you don’t get it up first, somebody else will.”

Social media can, to some extent, act as a halfway house between these two scenarios for some weeklies, plugging the gaps between print runs.

Les Zaitz, a former investigative reporter for The Oregonian and publisher of the Malheur Enterprise in Vale, Oregon (population 1,838), covered the standoff at the Malheur National Wildlife Refuge near Burns (population 2,738), a story which garnered national attention.126 127 128

Zaitz said that due to the weekly publishing schedules of many small-market newspapers “social media is a vital information lifeline for these communities, or can be,” adding: “I was frankly astonished in Burns as I did my reporting how my personal audience in Harney County and Burns grew by the hour because people were so starved for information, and they were served only by a weekly newspaper that could only come out once a week.”

Weekly, small-market newspapers, like their daily and metro counterparts, understand that audience expectations around the availability of content is shifting. Although change may be coming more slowly, the external pressures which are reshaping the speed with which news and information is disseminated and consumed is coming their way.

The new model journalist

The journalism profession is changing rapidly.129 As a result, the majority of newsrooms are unrecognizable from how they looked at the start of the new millennium.

Many journalists are now expected to demonstrate an ever-increasing range of skills, including: being able to write, shoot video, take photographs, input their copy into a content management system, identify pull-quotes, and produce social media content for a variety of platforms.

Newsrooms at small-market newspapers are not immune from these changes. In our 2016–17 survey of journalists at small-market newspapers, seventy percent of respondents told us they spent more time on digital-related output than they did two years ago, and nearly half (forty-six percent) said the number of stories they produce has increased in the past two years.130

As newspapers have laid off personnel, remaining staff have—in many cases—needed to grow and develop their skillsets. In our interviews, editors described videographers who were being asked to learn photography (and vice versa), while many traditional beat reporters are required to write for the website, newsletters, live blogs, social channels, and the original print publication. Each of these channels requires the flexing of different writing muscles. Meanwhile, even the smallest outlets are embracing opportunities to shoot video and photographs for social, as well as broadcast on Facebook Live.

Because of this, new and emerging skillsets are being increasingly valued by newsrooms, with newsrooms restructuring to create audience teams131 and engagement specialists.132

Lauren Gustus, the former executive editor at the Coloradoan in Fort Collins, Colorado, explained how her small newsroom (thirty to forty people) had been reconfigured to include a dedicated ten-person engagement team. Part of their charge, she explained, was “talking with readers across any of the platforms that we operate on and that our readers operate on.”

Others are following suit, although based on our conversations, the core skill requirements at small-market newspapers continue to be quite traditional and mainstream.

It will be interesting to see if these differences remain, or if emerging skill areas will simply be absorbed into the tasks expected of journalists in the digital age. With many journalism schools beginning to teach or place greater emphasis on these emerging skills, the next generation may automatically bring these sensibilities to the newsroom as part of the perpetual evolution and transformation of journalistic practice that is happening across the industry.

Final thoughts on changing journalistic practice

As we have seen, journalism is an evolving profession. The pace and extent of this change varies from outlet to outlet, and many journalists may find this evolution rather daunting.

Nonetheless, as Margaret Sullivan famously said, “These days, being a journalist shares at least one quality with being a shark. If you’re not moving forward, it’s over.”133

Small-market newsrooms across the country are moving forward by embracing social media and video, engaging with analytics and metrics tools, and reevaluating their publishing practices. These trends, and arguably the pace of change, show no signs of slowing.

Evolving Principles and Philosophies

Alongside changing revenue models and developing journalistic practices, some small-market newspapers are also responding to digital disruption by reevaluating their approach to local journalism. This goes beyond simply changing what they do, to embrace how and why they do it, too.

During our interviews, we heard about how some previously long-held journalistic tenets and behaviors were potentially being challenged, as local journalists put their profession under the microscope.

In this section we explore five of the most interesting ideas to emerge from our conversations.

The value and prominence of partnerships

Historically, the local newspaper industry has not been great at collaboration. According to Tom Glaisyer at the Democracy Fund, part of the reason for this is that the sector has always been “rooted in a cultural independence.”

“Part of their strength was in being independent,” he said, but this is beginning to change.

Although this is unfamiliar territory for some publishers, there are some success stories. In addition, funders such as the Geraldine R. Dodge Foundation and news incubators such as J-Lab134 have often made partnerships between publishers a prerequisite for financial support.

“Everything we did in New Jersey was rooted in partnerships,” said the Democracy Fund’s Josh Stearns, who previously oversaw Local News Lab, an initiative from the Dodge Foundation to help local news sites develop new and sustainable business models. The nature of those partnerships included information sharing, joint ad sales networks, and collaborative reporting.135

In Virginia, a partnership between the hyperlocal news website Charlottesville Tomorrow and newspaper The Daily Progress has resulted in over 2,000 stories written by Charlottesville Tomorrow staff published in the Progress. According to its website: “Charlottesville Tomorrow produces more than 50 percent of the newspaper’s content related to growth, development, education and local politics.”136

As Brian Wheeler, executive director at Charlottesville Tomorrow, recounted to us:

In 2009, The Daily Progress newsroom had shrunk dramatically, from about forty-five people to about eighteen. The managing editor approached us. He was looking for other things they could have on their website . . . and they finally reached the point where they said, “We could do more in partnership with you than trying to work against you.”

So, the partnership was a simple one-page, back-and-front memorandum of understanding between myself and the editor. There were no lawyers involved. And it was, in 2009, the first of its kind in the country where a nonprofit was doing beat reporting for a daily newspaper.

At the present time examples like this are the exception rather than the rule, but they offer an interesting precedent that others can follow. Moving forward, we believe that small-market newspapers will increasingly see the value that partnerships with local, regional, and national entities can potentially bring.

One area ripe for collaboration is greater links between local newsrooms and national nonprofits. As Jane Elizabeth, senior manager for the Accountability Journalism Program at the American Press Institute, reflected, partnerships between local news outlets and nonprofits like ProPublica and The Marshall Project would be especially beneficial. There are some national publications reaching out to local newsrooms, Elizabeth said, “but I sense that there’s hesitancy in the local newsrooms” that don’t always see how they would benefit. “I think that’s a big opportunity that a lot of local newsrooms are missing out on.”

In sum, although partnership requires a culture shift on both sides, it’s a direction many newsrooms are already heading in.

Engagement

Engagement was the media buzzword of 2016137 and a key topic of conversation in our discussions with industry practitioners. There’s no standard definition of this term, although it’s a label which can be applied to a variety of offline and online publisher-audience relationships.

For many of our interviewees, their understanding of engagement goes beyond traditional measurements such as subscribers, unique users, or time on site. Instead, it’s part of a wider dynamic in which they are reassessing their journalistic role.

Some newsrooms are already recognizing that this relationship needs to be more two-way, going beyond historic norms. Engagement in this context is about more than just outreach. It involves active listening and more of a focus on impact.

J-Lab’s Jan Schaffer talked about the importance of small-market newspapers needing “to figure out how not just to cover community, but to build it as well.” That, Shaffer suggested, means papers listening to the community and looking to do more than just find a great quote or angle for a story. “The engagement that counts,” Schaffer said, is, “wow, we helped our community fix a problem, do something better. And I think that’s still a skill to be learned.”

This skillset requires a shift in approach and practice, but it is in line with the “good neighbor” role that research has shown audiences value.138 139. We believe that engagement can be one of the ways in which small-market newspapers can reassert their relevance in the digital age.

As Lauren Gustus admitted, titles like the Coloradoan need to “demonstrate the value of a local news organization and that it goes beyond the printed product.” To help achieve this goal, she reconfigured her thirty-person newsroom to create a ten-person engagement team charged with finding opportunities to “further our relationship with our readers in a meaningful way.”

Events, putting community members on the editorial board, and engaging with readers on and off site across different digital platforms, are just some of the mechanisms the Coloradoan and others have deployed with this goal in mind.

Engagement strategies, both online and offline, also need to evolve and be refined. This is particularly true when it comes to social. Amalie Nash, at the Des Moines Register, highlighted Facebook and Snapchat as two examples of this digital dichotomy.

Noting that in the month prior to our interview, “We got fifty-three percent of our traffic from Facebook,” Nash nonetheless said her newsroom constantly debated where they should place their digital bets:

Snapchat is a great example of that. A lot of news organizations are putting strategy and time behind Snapchat, not making any money, not bringing anyone into your site because there’s no way to link or anything from it. Are you hoping the money follows, or are you doing it just because that’s where an audience that you’re to reach is, and you’re hoping they will hear our message and then come back to your site? What does success look like on a platform like that?

Others highlighted how their approach had changed over time, with the The Texas Tribune’s Emily Ramshaw noting that “two years ago we were streaming all of our own events live and on our website, and now we’re using Facebook [Live] to do the bulk of what we do.”

Opportunities for engagement, built around the inherent proximity to the audience which small-market newspapers enjoy, were among the key reasons why many of our interviewees were more optimistic about the future than perhaps we had expected. These characteristics contributed to the contrasting opinions expressed by many about the future for metros.

As a former editor at a major metro and also a small-market newspaper reflected:

I think there is an opportunity for small newspapers more than the larger ones . . . to actually form a relationship with the community still . . . Because you might know your neighbor, who was in the paper yesterday. And the smaller newspapers do a better job of getting more people in the paper than the larger ones as well.

There are those kinds of opportunities in smaller newspapers that aren’t there at larger ones. So, I think that forming that type of relationship with the community is still there in smaller papers. And I think it’s more difficult in the metro markets.

Objectivity, advocacy, and solutions

Alongside a growing interest in the opportunities presented by partnerships and engagement, a number of interviewees also shared with us some of their evolving thoughts on their wider journalistic philosophy. These conversations touched on a number of issues including objectivity, advocacy, and the emergence of newer journalistic practices such as solutions journalism.140

The physical closeness to their audience enjoyed by small-market newspapers has previously presented challenges for some journalists. One editor described how, in a bid to be detached and impartial, journalists can sometimes live “like a monk” outside of the newsroom.

Nowadays, there’s an increasing sense that this level of abstinence and community celibacy isn’t necessarily needed. Local journalists can still be active in their community and indeed advocate for it, several interviewees argued, without jeopardizing their journalistic integrity.

In keeping with this, we heard a growing recognition—and level of comfort—with the notion that local journalists are part of the community they are reporting on. They bump into readers while getting coffee, picking their kids up at school, or shopping for groceries.

“To pretend that you can’t, or pretend that you don’t live in the community that you cover, and that you’re not affected by the events that you’re reporting on, and that you have a stake in them, it’s ludicrous,” argued Joel Christopher.

In the process of accepting the implications of this dynamic, small-market newspapers are finding they are able to open themselves up to newer ideas such as solutions journalism,141 by not just shining a light on problems, but on potential remedies, too.

The Seattle Times, with its Education Lab initiative,142 has been active in the solutions space for some time.143 Others are following in its footsteps.144

Under Joel Christopher’s stewardship, for example, Gannett’s ten Wisconsin papers embarked on “Kids in Crisis,”145 a statewide examination of mental health issues related to children and teenagers. Alongside traditional reporting methods, the papers “advocated clearly and explicitly for changes that we think that need to be enacted in the state,” Christopher recalled—an editorial approach which he believes is part of evolving journalistic practice at some local newspapers.

“Would we have done that ten years ago? Hell, no,” he said. “I don’t think we would’ve. I have no problem with [this]. I don’t think it in any way changed [the] journalism because of fear of losing objectivity or becoming an advocate. I think it actually focused and strengthened the reporting.”

Impact aside, Keith Hammonds, president and COO at the Solutions Journalism Network, also argued that this model can be more satisfying for reporters:

Reporters and editors in this project have discovered is that doing these deeper feature stories with a solution orientation . . . [are] also more meaningful to journalists. There is a manifest leap that you take from doing the rogue reporting on school boards and police blotter to doing a deeply reported piece that not only addresses concerns in the community, but attaches those concerns to pathways to constructive discussion.