WHY WOULD A COMPANY LIKE FACEBOOK Inc., which earns almost all of its revenue from advertising, choose to adopt an apparently anti-advertising technology like end-to-end encryption?

Of the big tech companies, Facebook Inc. seems to have the worst brand perception among consumers. In a survey conducted by Fortune and Harris Poll, only 22% of the respondents said they would trust Facebook Inc. with their personal data. The company has been part of widely publicized scandals such as the Cambridge Analytica debacle and the Russian disinformation campaign during the 2016 elections, and many more. It has been accused of endangering democracies and enabling horrific crimes. It has repeatedly apologized and promised to change its ways, but its privacy scandals and abuses of its power have repeated just as frequently.

By its own admission, the company’s priorities are shifting. Mark Zuckerberg, the CEO of Facebook Inc., recently outlined his plan to merge the messaging infrastructure of all his apps—Facebook, Instagram, WhatsApp and Messenger—and make this entire messaging infrastructure entirely end-to-end encrypted. This would render it impossible for Facebook Inc. to read private conversations between users and run advertising based on the content of those conversations. In the blog post outlining his plan, Zuckerberg also wrote that private messaging on WhatsApp and Messenger would eventually be bigger than the social networks of Facebook or Instagram. At the recent F8 conference keynote, Zuckerberg even claimed that “The future is private”—a big shift in direction for the company.

This article argues that that the firm is facing business challenges that require drastic steps, and its recent turn towards encryption is less about a fundamental change of heart, and more about addressing ongoing problems of user attrition, competition and government regulation.

Notes: For clarity, Facebook, the parent company, is referred to herein as “Facebook, Inc.” and Facebook, the social network, is simply “Facebook.” The author worked with Tencent’s messaging app in Asia, WeChat, between 2013 and 2015. WeChat competes with WhatsApp.

Facebook doesn’t care about privacy nearly as much as the media does, but then, neither do its users

Since its earliest days, Facebook Inc. has had a poor reputation when it comes to its users’ privacy. Ignoring privacy has been a good growth strategy: The business has amassed a user base of 2.7 billion monthly active users, and those users don’t seem to care much about privacy or the company’s privacy scandals, even today. When Facebook Inc. launched Facebook’s newsfeed (which meant that all status updates and photos started appearing on friends’ feeds without the users opting into the change)—it faced a huge media backlash. In terms of actual user behavior, though, as Facebook’s then-product manager of newsfeed stated in a video, engagement doubled. Facebook, Inc’s employees had learned that users didn’t care about privacy at all. In January 2010, CEO Mark Zuckerberg stated publicly that the age of privacy as a “social norm” is over.

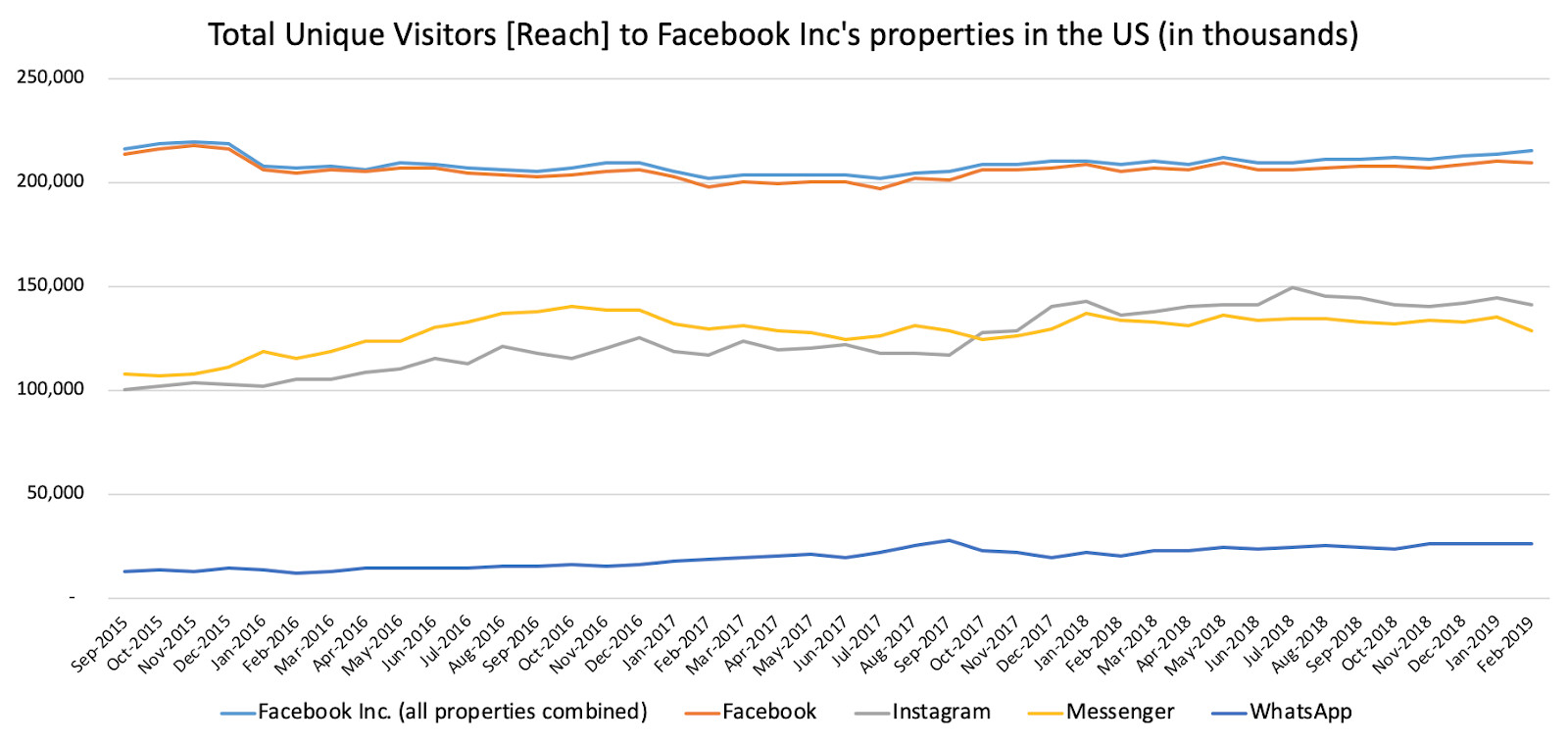

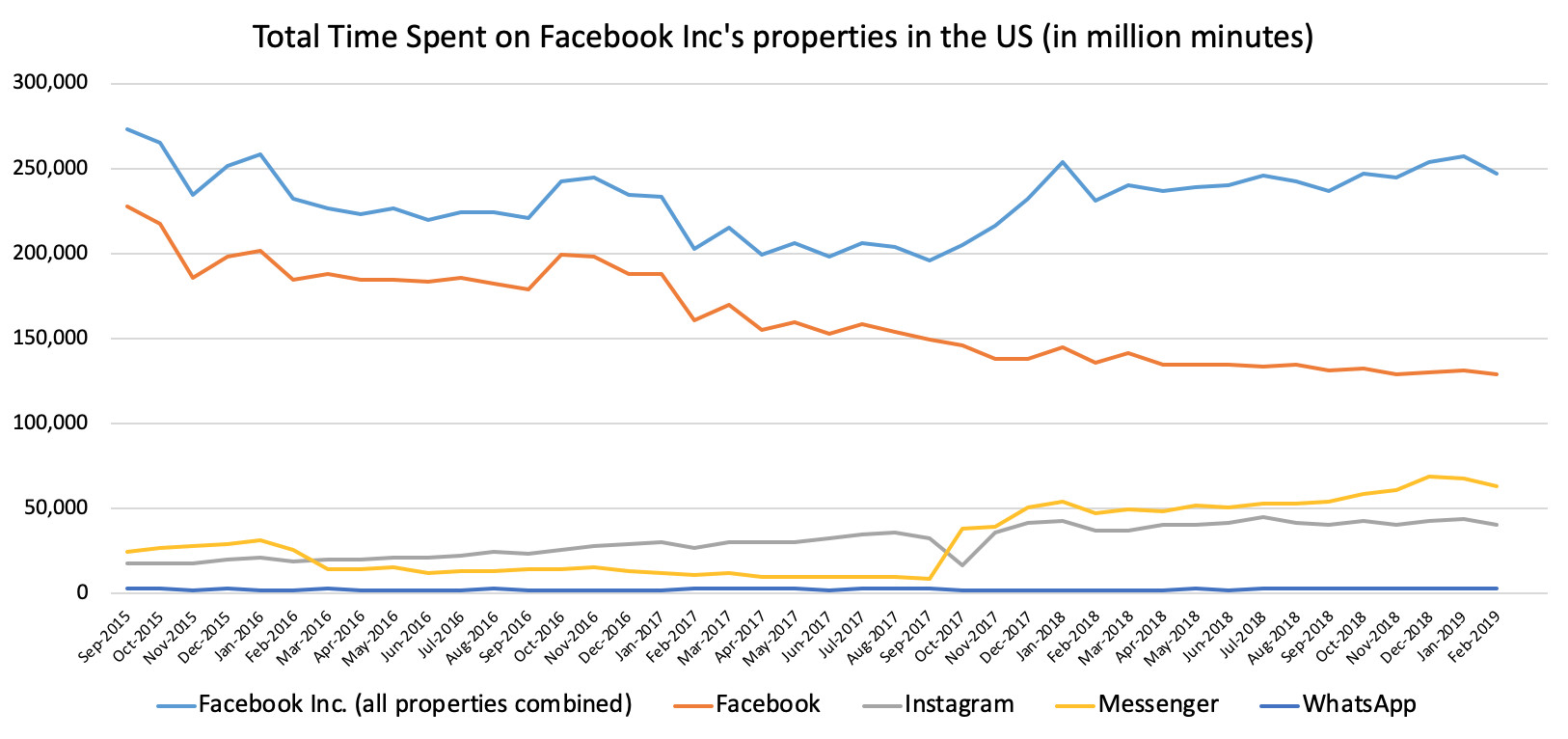

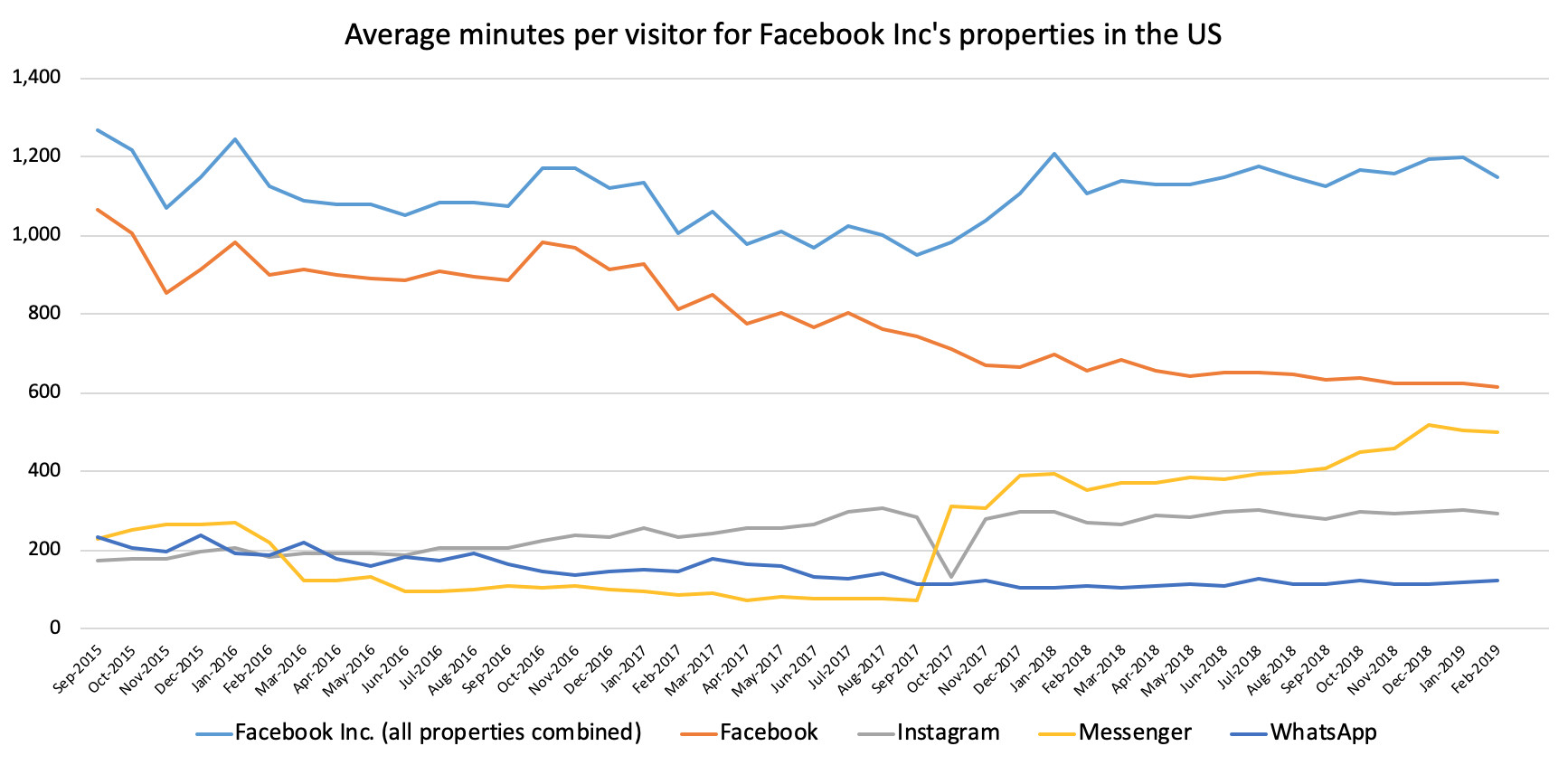

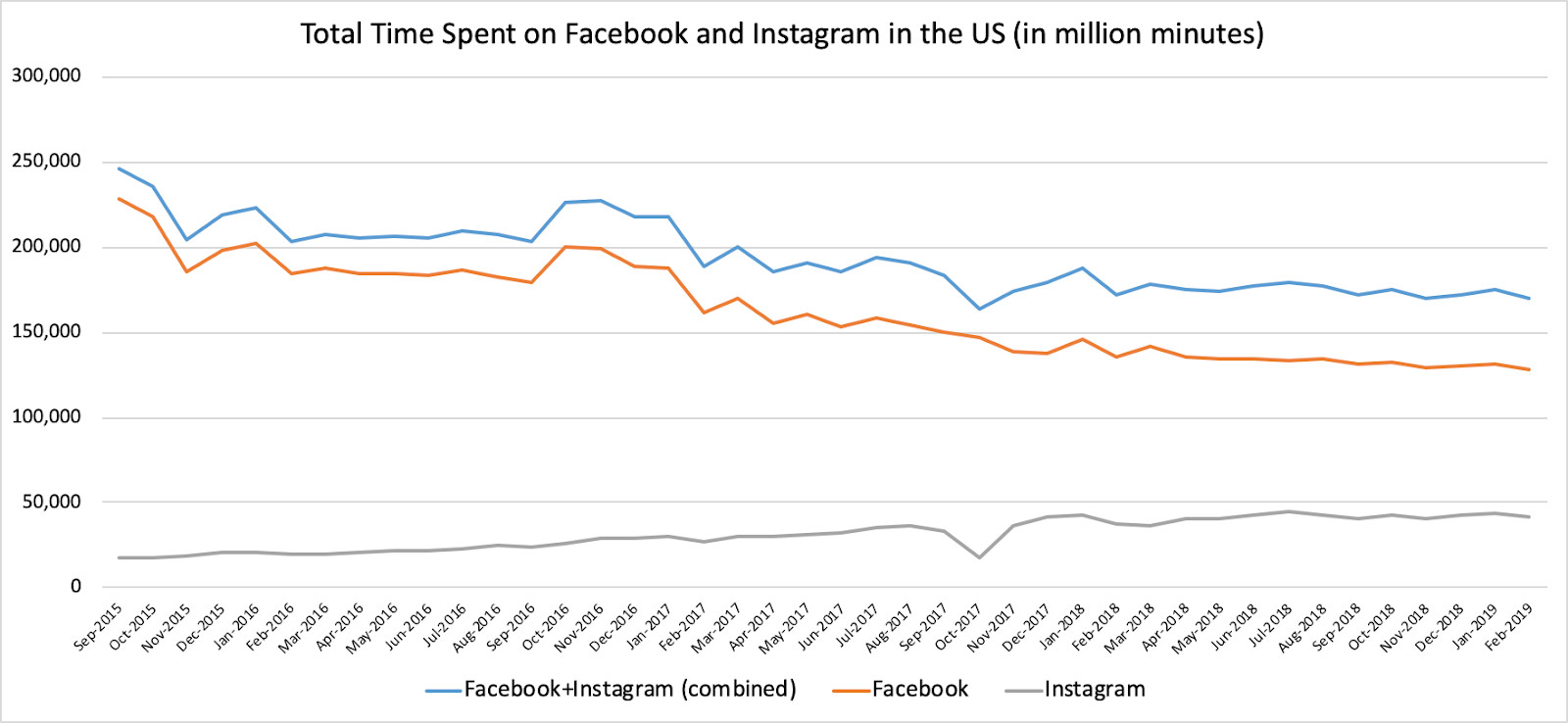

Most of Facebook’s users were unaffected by media coverage of its scandals, according to two measures, reach and time spent, available from the internet audience measurement firm ComScore. “Reach” indicates how many users visit Facebook proper at least once a month, and “time spent” tells us more information about a critical factor, i.e. engagement.

As the above graph shows, from September 2015 to February 2019 Facebook’s unique users in the U.S., Facebook’s core revenue market, fell from 213.7 million users to 209.5 million users, a minor drop in three years.

Over the same period, the average number of minutes per visitor for Facebook in the U.S. dropped from 1,067.9 minutes in September 2015 to 613.6 minutes in February 2019. This is almost a 40% drop in over 3 years—but public knowledge of Facebook’s role in the supposedly damaging Cambridge Analytica scandal and its months of fallout dates back only to the first media reports of the scandals in March 2018.

Over the period measured, the annual rate of decline in average minutes spent per visitor per month has been relatively constant, even decreasing slightly. If Facebook users were indeed concerned by Facebook’s privacy scandals, then ideally we should have seen a sharp, immediate decline in time spent after details of Cambridge Analytica scandal emerged in March 2018. But since this did not happen, it suggests that the public is indifferent to Facebook’s privacy scandals. In November 2016, after the US elections, the total amount of time spent on Facebook increased for two months, likely because of users engaging with their friends around the election news. But in the longer term, the decline of Facebook seems secular, and not a result of privacy scandals, PR mismanagement or unfavorable press.

The users of the world’s largest social network are spending less and less time on the product, and we can safely say that the company’s efforts at stopping the decline seem to have been ineffective for at least the last 4 years. While its user numbers are still healthy, there is no doubt that Facebook is losing time spent and attention fast, and with the loss of attention, user loss seems likely to follow. Facebook has been seeing a decline in its user growth for some time now; the company has stopped sharing the monthly active user number for individual properties since February 2019.

Will the growth of Instagram, Messenger and WhatsApp replace the decline in Facebook? Probably not.

Facebook Inc.’s core monetization properties are Facebook and Instagram. The other two properties, Messenger and WhatsApp, aren’t significant money generators because ads are much harder to deliver through messaging apps. So while Facebook Inc. would continue to make some money from them, both messaging apps hardly compare relative to the other two (Facebook and Instagram) in terms of share of absolute revenue—or revenue growth.

Total time spent on Facebook is declining significantly faster in the US, which is Facebook Inc.’s biggest market by revenue and profit share. While Instagram user growth has been healthy, and continues to gain a higher share of new ad revenues for Facebook Inc., it doesn’t—and may never—balance the loss of total time spent from the decline of Facebook. This means that the total time spent on Facebook combined with Instagram in the US is going down. This should result in Facebook Inc.’s “feed inventory” (on which ads run) going down significantly.

Source: ComScore US, Media Metrix (Multiplatform)

Instagram’s pace of growth is not currently fast enough to fill the gap left by Facebook because of the longer time spent on Facebook by its users. Ad rates on Facebook continue to rise, which seems superficially like a good sign—but the real reason may lie in this decline in time spent on the service, which in turn decreases the ad inventory the company has to sell.

Antonio Garcia Martinez, a former product manager at Facebook inc, responsible for building their advertising division, and known for the book “Chaos Monkeys” where he recounts his time at Facebook has suggested on Twitter that the success of advertising on Instagram won’t be able to reverse Facebook’s decline.

In the short term, Facebook Inc. has been able to weather these changes by increasing its ad loads, and since Facebook continues to have unmatched ad targeting capabilities based on its extensive data-capturing machine, it continues to deliver better returns for the marketers and will likely continue to make more money in the short-to-medium term. But looking only at revenue as a proxy for the health of Facebook Inc. can be misleading.

In fact, Facebook Inc. already accepts that it has hit the peaks on not just Facebook but also on Instagram as far as both services’ newsfeed are concerned. Facebook has been trying to manage its decline in the US by copying features such as Stories from competitors such as Snapchat. Stories not only allowed the parent company to hold off competition from Snapchat, but to increase its ad inventory and reduce its ad prices somewhat, keeping Facebook, Inc. competitive when it comes to bidding for advertisers’ budgets.

But the decline in time spent is so severe that even Stories may not be enough in the long term for Facebook Inc.

Can’t Facebook Inc. always buy the next Instagram or the next WhatsApp?

Mergers and acquisitions are a critical piece of corporate strategy and Facebook Inc. has an impressive record when it comes to acquisitions. The company bought Instagram for $1 billion when it was at 30 million monthly active users; Instagram’s estimated worth is over $100 billion as of a year ago, and it has over a billion monthly active users. The firm also picked up WhatsApp when it was at 400 million monthly active users; the messaging app today boasts of upwards of 1.5 billion monthly active users. Facebook Inc. even tried to buy Snapchat for $3 billion but was rebuffed. The firm has hamstrung competitors it couldn’t acquire by copying their key features, adding Stories to Facebook and Instagram in imitation of Snapchat, and using its distribution advantage among its properties — Facebook, Facebook Messenger, Instagram and WhatsApp—to cross-promote its products.

Many have called this behavior anti-competitive and monopolistic and called the company responsible for stifling new innovation in the social and messaging space. This, combined with the company’s disregard for user privacy, has led to heavy public focus and regulatory scrutiny and calls are getting stronger for Facebook to be forbidden from buying any new social or messaging products in the future. Some have even called for a break-up of Facebook Inc. that would make Instagram and WhatsApp separate companies.

The nature of the next big thing is that it may come from anywhere. Facebook is currently facing competition in the social content space from a new Chinese player — TikTok — which has already grown to over 1 billion monthly active users globally. Today, Bytedance, which owns TikTok, is valued over $75bn and is backed by Softbank. Such a high valuation makes it almost impossible for Facebook to acquire TikTok, and so Facebook has launched a copycat app called Lasso. With the exception of Messenger, Facebook’s standalone apps have failed, notably, its clone of Snapchat, Direct, its news app Paper and the initial response to Lasso too has been muted. TikTok’s growth in the midst of Facebook’s attempts to market its own alternative appears to demonstrate that Facebook may not be able to crush all its competitors.

The biggest threat to Facebook Inc. is not competition but government regulation

Calls for Facebook Inc.’s break-up from regulators all over the world are getting stronger. Many noted commentators and even ex-employees now agree that Facebook Inc. probably should never have been allowed to buy Instagram or WhatsApp and that it should definitely not be allowed to buy another social network or messaging app in the future. And Facebook Inc.’s consistent privacy scandals, even if they haven’t affected consumer behavior, have significantly riled regulators and prominent privacy advocates, to the extent that European Union’s regulations around GDPR and upcoming regulations seem particularly aimed at Facebook.

To counter this threat, Facebook Inc. is trying to do two things carefully. First, it is adopting end-to-end encryption on top of a single messaging infrastructure across all products. The adoption of end-to-end encryption enhances Facebook Inc.’s reputation in the eyes of privacy-obsessed regulators everywhere. The purchase of WhatsApp has bought respect from privacy activists, since the end-to-end encrypted nature of WhatsApp means that the company can’t read any messages or chats of its users.

Switching messaging to end-to-end encryption also helps Facebook keep down its content moderation costs, which keep ballooning up for the company. Facebook has already said that it has over 30,000 people working in the area of safe content. An investigation by Casey Newton of The Verge found that the working conditions were very poor for most of such contractors, and they were often underpaid. After the investigation came out, Facebook promised to do more and increased the workers’ wages to $15 per hour. Switching to complete end-to-end encryption means that Facebook Inc. doesn’t have to take responsibility for moderating misinformation and viral hoaxes on its messaging networks since it can’t moderate what it can’t read. The authors of this article proposed a solution last year in another CJR piece, suggesting a way to moderate encrypted content without breaking encryption. But so far, WhatsApp and Facebook Inc. have refused to take responsibility for content moderation on their encrypted messaging apps and conversations, and if it continues to do so, shifting its messaging infrastructure to end-to-end encryption would likely reduce costs. Facebook’s former security chief, Alex Stamos, cautioned attendees at a conference last week not to discount his old employer’s self-interested motivations for embracing encryption.

Second, the company is unifying all of Facebook Inc’s apps into a single messaging infrastructure. This would mean that all the apps would be linked by a single consumer identity. Newton has argued that it’s easier to call for a break-up for Facebook Inc. when its products are largely separate; it would be much harder to do so if all the company’s brands were effectively a single product with shared identities, logins, and previous interactions. Regulators might be warier of breaking up Facebook if doing so would break the consumer’s experience of the product.

By shifting to an encrypted but combined messaging infrastructure, Facebook Inc. can have its cake and eat it too.

When Facebook, Inc. bought WhatsApp in 2014, CEO Mark Zuckerberg promised full independence to Jan Koum and Brian Acton, the app’s founders, who had said at the time of purchase they planned to make WhatsApp completely end-to-end encrypted.

I pointed out in November that even though WhatsApp is end-to-end encrypted, the meta-data is not. Many important details including mobile number, device id, and participant identity are still available to Facebook, which can use its profiling and targeting data to run targeted ads on WhatsApp Status. The moment Facebook Inc. forced all WhatsApp users to link their WhatsApp accounts to Facebook, their concept of privacy was gone forever.

By linking of all four properties together, Facebook Inc. would be able to watch over key activities and relationships between its users, even though the full text of some of its communications would be encrypted—hardly what Koum and Acton envisioned.

Social feed-based products like Facebook and Instagram will almost certainly remain unencrypted. In addition to data that it derives from its own feeds and data that users willingly share with Facebook, such as their date of birth, gender, relationship status, the names of their schools and employers, and so on, Facebook Inc. gets huge amounts of data from tracking pixels across the web. The Facebook “like” and “share” buttons that one sees on many news websites help in this regard, as does Facebook’s software developer kit, which many app developers use to enable Facebook logins and retargeting options for ads. The private conversations between users such as on WhatsApp, Messenger or Instagram Direct messages (popularly called DMs) are a poor place to put advertising, and the company doesn’t lose much by switching to end-to-end encryption in messaging. It is able to improve its privacy-related credentials everywhere, including in the eyes of regulators, governments and privacy activists, though.

Zuckerberg has repeatedly predicted a future dominated by private messaging rather than public social networks. Facebook Inc boasts 1.5 billion users on WhatsApp and over 1 billion users on Messenger respectively, but multiple messaging apps such as Telegram (now at 200 million monthly active users), Signal, Threema, Wire, etc. have been able to increase the size of their user base by promising full end-to-end encryption and greater user privacy on their platforms. Their user bases can’t threaten Facebook Inc.’s just yet, but that dynamic can also quickly change. Apple’s iMessage, the leading messaging app in the US, is end-to-end encrypted, making end-to-end encryption table stakes in the messaging game for any player aiming to achieve a significant scale outside of China. Messaging is now a more highly competitive space than social networking. Even a leader like Facebook Inc. can’t risk losing 200-300 million users to competing players—such a loss could unravel the entire network. Facebook Inc.’s adoption of end-to-end encryption across its entire messaging infrastructure gives it parity with these competitors, and stave off these threats.

By unifying its messaging infrastructure and the identity of all its apps, Facebook Inc. can continue to have the advantage of a far more lucrative business model that allows it to serve ads using data from its two products that aren’t end-to-end encrypted—Facebook and Instagram—across all four of its products, including the completely encrypted WhatsApp and Messenger. The combination could include meta-data linking a common Facebook Inc. identity. Despite moving to end-to-end encryption in messaging, this strategy would prevent any detrimental effect on revenues of Facebook Inc., and competing end-to-end encrypted messaging products would still be struggling to find a viable business model.

Since Facebook is declining, its parent company is wise to resist efforts to split off recent acquisitions, even if, like WhatsApp, they are difficult to monetize on their own. Facebook can help Facebook, Inc monetize end-to-end encrypted apps using non-encrypted metadata to match users to their Facebook profiles and other, extended datasets the company uses to serve targeted ads. Then it can serve them to WhatsAppers. Without its recent acquisitions, Facebook, Inc.’s only real star would be Instagram, which would be vulnerable to new competitors. So, it’s absolutely in Facebook Inc.’s interest to avoid its break-up, and to do so, now supporting and adopting privacy is in the interest of the company. However, as explained above, this privacy isn’t being provided to the users, who would now rather find themselves tracked even more closely by Facebook Inc. with even better advertising targeting capabilities, but it’s a strategy to thwart away regulators. Facebook’s recent settlement with FTC in the US with a $5 billion fine had plenty of future leeway for the company written into the fine print, so that’s one major regulator carefully managed away. To ensure that it doesn’t invite any further regulatory attention, Facebook Inc. even halted its acquisition efforts with Houseparty, a video-focussed social network app.

Facebook Inc. hasn’t traditionally cared about privacy because ignoring it is profitable, and end-users have never cared about it in significant numbers, either. However, now that Facebook is struggling for relevance and questions over monetization capabilities of WhatsApp and Messenger continue to linger, Facebook Inc. is facing its first real challenge as prominent figures like Democratic senator and presidential candidate Elizabeth Warren and former state attorney for New York Tim Wu call to split of Facebook’s social networking business from its messaging empire. While the company now seems to embrace privacy in the aftermath of multiple big scandals, one can obviously see how privacy is also being used consciously as a strategy by the company to keep regulators at bay. By embracing end-to-end encryption among its increasingly popular messaging apps on the one hand and combining the entire messaging infrastructure of all Facebook Inc. products into a single identity layer, Facebook Inc. would be able to make its break-up less desirable to regulators and apparently address privacy concerns without hurting its ad business and in a way that might stave off secular declines in its market share. Facebook Inc. has chosen privacy, but only in a way that would leave it, and only it, on top.

Harsh Taneja contributed to this report.

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.