With colored pencils and sharpies scattered across a table, residents of Germantown, a majority-African American neighborhood in Northwest Philadelphia, narrated images they had drawn as part of a focus group discussion. On one side of a paper, where several had made line drawings of police cars or guns, participants had drawn how they felt their community was represented in local news media.

“You see somebody’s [mother] in a bonnet or a rag crying or fighting,” Angela[1] explained of her picture. “It seems like when I do turn on the news, it’s always something negative being reported, whether it be about the schools or about the communities.”[2]

On the other side of the paper, Angela and others drew how they wanted their community to be represented. Angela explained that she wanted the news to offer a fuller portrait of the neighborhood—“positive, negative, people working together to show a real representation of what this neighborhood is instead of scaring people to a pulp.”

Angela’s words resonated with a previous study in which other residents of this neighborhood told us they felt stigmatized by negative coverage—and that crime was overreported while many issues of substance received superficial coverage, if any. Initiatives to address these deficits sprouted up, and we returned to Germantown to find out whether and how these programs, had the potential to improve relationships between residents and local newsrooms.

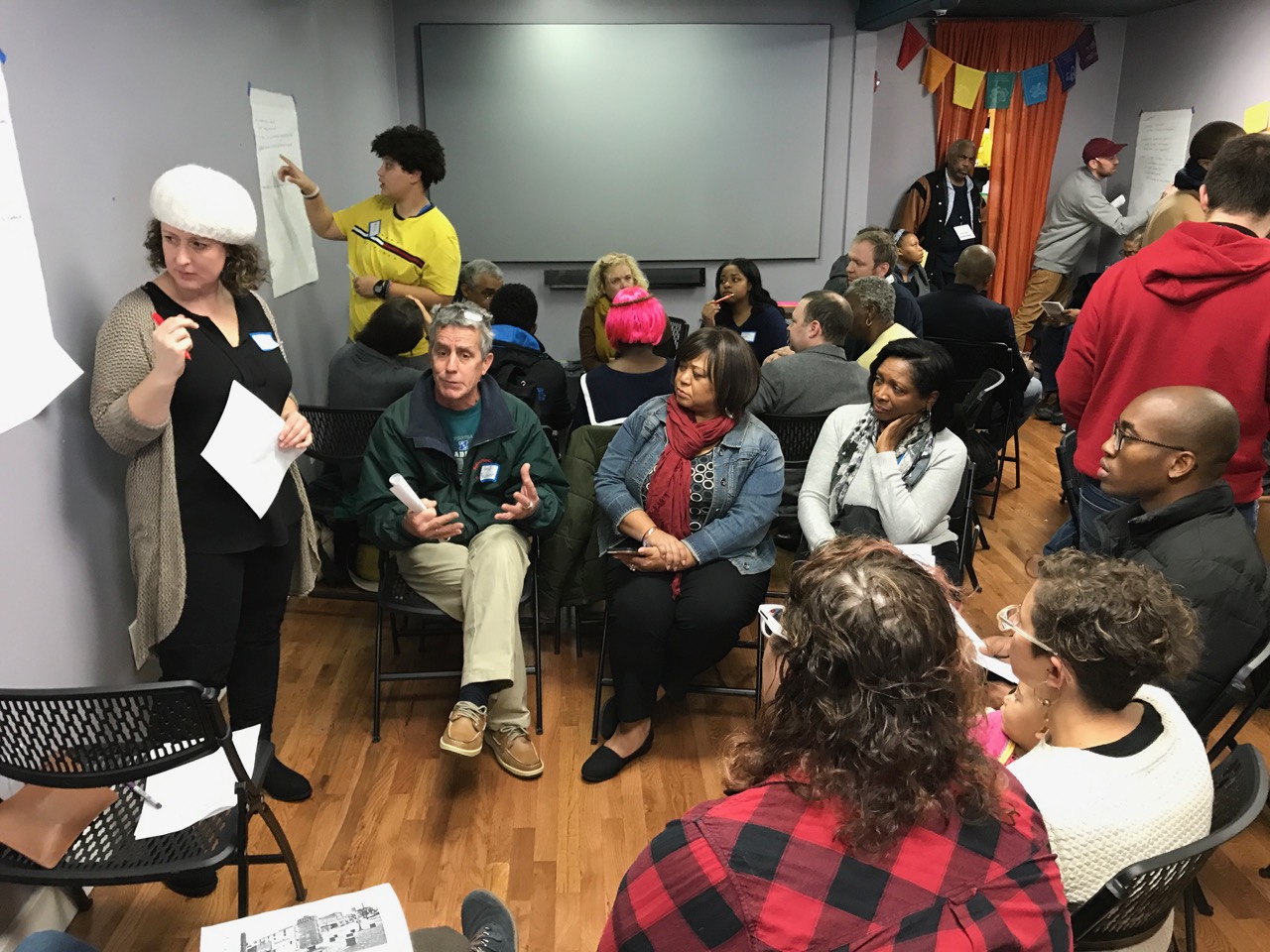

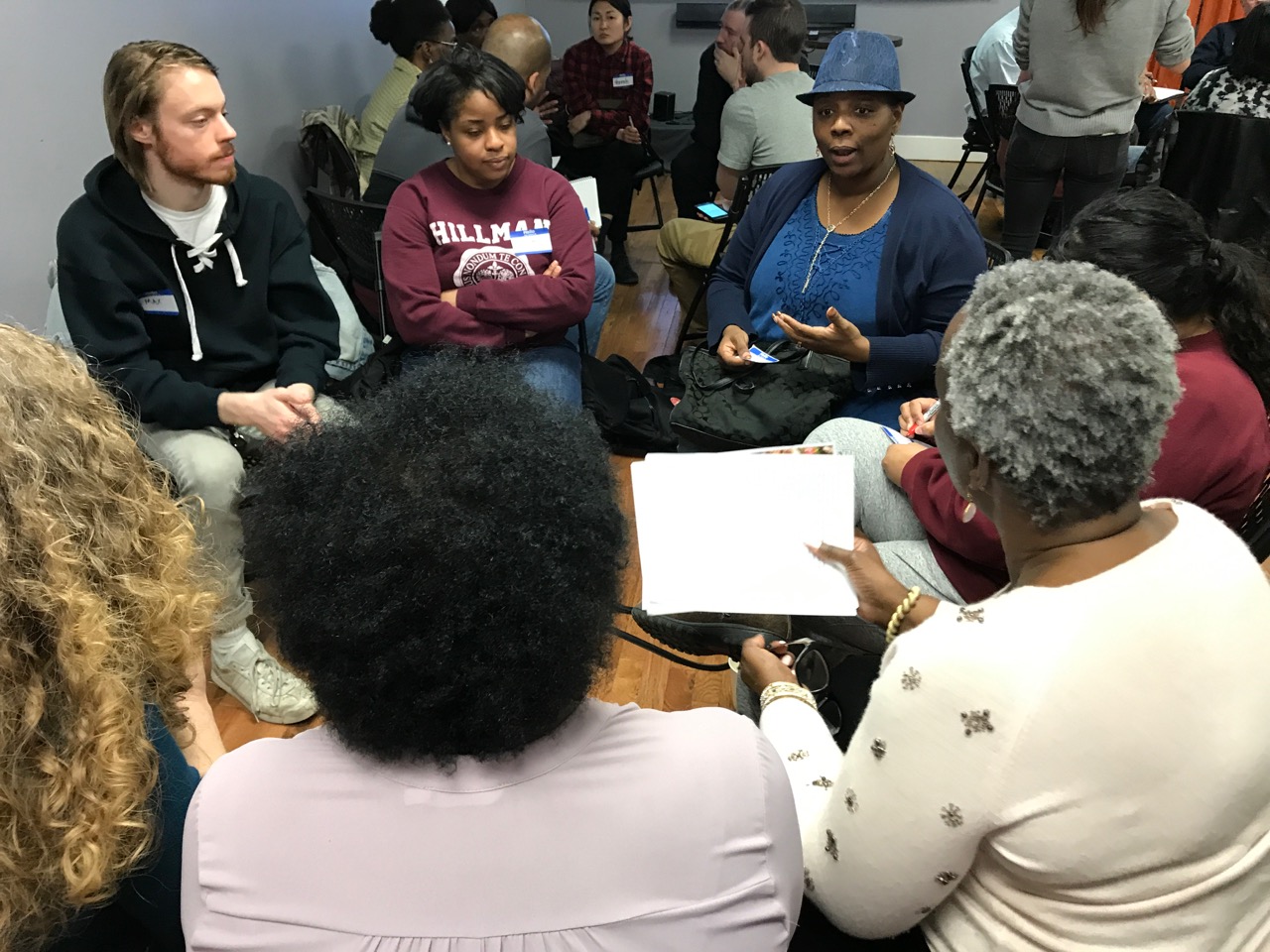

In this study, we focused on two interventions. First, we looked at NPR affiliate WHYY. As part of a larger initiative to build the cultural competency of their newsroom, the station held community workshops and meetings between staff reporters and community leaders. We also looked at the Germantown Info Hub, an engaged-research and community journalism project we helped to facilitate in response to recommendations that emerged from our previous study. This project was in a pilot phase during this study. It included a combination of community reporting, face-to-face tabling and mobile texting, and community discussions. The latter also involved WHYY.

We explored whether either intervention could change how residents perceived media coverage of their community. We also explored what residents meant when they talked about trust in local news, and how they thought about coverage they perceived to be intended for their neighborhood as opposed to coverage about their community intended for broader metro-wide audiences.

To address these questions, we held five longitudinal focus groups, in which we followed a group of 19 residents over eight months.[3] We were curious whether participants were encountering the two interventions on their own in the wild, and whether exposure to the content over time affected participants’ perceptions. For this reason, we sent half of the participants updates on programming from these interventions— a story covering Germantown, or a community workshop—as part of a regular email, which also contained other local news stories about Germantown. The other participants did not receive these updates. At the focus groups, we invited participants to reflect on news stories about Germantown, including examples from Germantown Info Hub and WHYY.

In these discussions, we found an overall enthusiasm for efforts to strengthen connections between local newsrooms and communities, as well as a number of areas where ongoing efforts needed improvement.

Nowhere to go but up?

In our initial discussions, when the interventions were just getting underway, we attempted to learn how residents perceived local news coverage of Germantown. As Angela’s comments suggested, their assessment was grim.

When participants expressed distrust or dissatisfaction with local coverage, they generally talked about some combination of three factors: perceived accuracy, respectful representation, and the perceived motives of the journalist or outlet.[4] Participants complained that reporters lacked an awareness of place and still seemed to make negative assumptions about Germantown. In one group, participants said that whenever something bad happened on Germantown Avenue, which runs through multiple neighborhoods, journalists reported that it happened “in Germantown” whether or not it was true.[5] At the same time, another participant said, “Anything good that happens in Germantown, they call [it] Mt. Airy (an adjacent, more affluent neighborhood).”

Others worried that exclusively negative coverage distorted the community’s reputation: “If I didn’t know any better and I was listening to that story, I would think that all of Germantown was a giant blighted area,” said one.[6] These observations were often followed by speculation that journalists had a dishonorable “agenda.” As one participant put it, “It might be a conspiracy theory but I believe that the media has some agenda on some level to keep certain neighborhoods’ value high and other neighborhoods’ value low.”[7] Participants said that they saw some coverage as about but not for local residents. During a discussion of a televised news story about Germantown, one focus group participant said the story seemed to be meant for “everyone else.”

“I think it’s the rest of the city saying oh wow, something really awful happened again in Germantown,” the participant said.[8]

Perceptions of public radio

When conversations shifted from a local journalism generally to specific outlets, perspectives varied more. We were especially interested in how residents viewed WHYY, because the station was planning community engagement activities in Germantown and other neighborhoods. As participants shared their sources for local news, several mentioned WHYY. A few said coverage on WHYY was “unbiased.” As one participant put it, “I don’t have to question whether or not the narrative is true.”[9]

Some relied on WHYY for local news, but others turned to the station mostly for its national news coverage. One participant complained that WHYY rarely covered stories about their part of the region: “We hear a lot more about what’s going on the Main Line (an area of the suburbs) or like outside of Philadelphia, or just like downtown and Center City. So, I don’t really trust that as like my local news source.”[10]

Without knowing what newsroom produced it, the group listened to a WHYY story about housing in Germantown . The response was mixed:. several said they appreciated the story and assessed the motives of the journalists favorably: “It just felt like they wanted the person that was listening to be informed. It wasn’t like a sway this way or that way,” said one.[11] But because the story was about an issue with which many participants were familiar, they were critical of the story’s details. One participant noted that the story did not mention the name of someone they saw as key: “It wasn’t very accurate. I mean, I’m very close to all the information and so it’s just one side of how they’re telling the story.”[12] In another group, participants suggested the story’s tone was not “pulling us in”:

I probably wouldn’t have listened to the whole thing. I think it would have been like blah, blah, blah, blah, okay, got it, and then I would have been done. I don’t think I would have had much patience for it. I was starting to fade in and out.[13]

Another member of the group suggested that the story needed “some kind of a hook so that I understand what it means to me.”

Outreach and intervention

After our first round of focus groups, we observed efforts to connect local journalists and Germantown residents—and we emailed participants announcements for some of these events.

As part of WHYY’s cultural competency project, the station held workshops where residents developed personal stories with the help of a professional trainer. These sessions were small and did not necessarily result in stories distributed by WHYY. But they took place between WHYY engagement staff and Germantown residents in Germantown—rather than WHYY inviting residents to come to WHYY’s studios in Center City.

The storytelling sessions did not involve WHYY reporting staff. The station’s reporters were involved in two other initiatives. First, as a follow-up to a training on culturally competent sourcing practices, reporters and editors met with community organization representatives and advocates. Then too, the WHYY staffers came to Germantown, meeting at the Black Writers Museum, a local cultural institution. Community representatives recommended reporters build relationships within the community and spend more time there. Reporters asked community leaders for a list of sources; the leaders refused, saying that the reporters needed to build trust first.

Additionally, WHYY participated in community discussions organized by the Germantown Info Hub, a community journalism project (which we co-facilitate with a project team and community advisory group) that seeks to improve the circulation of hyperlocal news in Germantown, and to offer fuller narratives of the community. These objectives grew out of our previous engaged research. The Info Hub puts at least as much emphasis on community outreach, organizing, and dialogue as it does on publishing stories. The project was just beginning during the period of this study.

With the Info Hub, we invited participants to discuss WHYY’s coverage of a plan to redesign a commercial corridor in Germantown, and the topic of redevelopment itself. Community members talked in small groups with reporters and editors from WHYY, where they offered feedback on the story and suggestions for follow-up. The group criticized WHYY’s overreliance on the same sources. The reporter admitted to contacting a particular source frequently because she “gave good quotes,” and community members objected, saying it was important to them to hear from a greater range of people, including those who may be less accustomed to speaking in soundbites. Editors said they hoped to build relationships with community members that would expand their interactions with potential sources.

Community feedback on stories

Half of our participants received monthly emails sharing stories about Germantown, and, when available, announcements of WHYY or Info Hub community discussions or storytelling events. All participants were invited back for a second round of focus group discussions. This time, before getting into specific stories and their recommendations, we invited participants to draw images representing a few local news outlets—including WHYY.

“It’s a terrible drawing,” Robert said of his drawing of WHYY. “I drew the world, and there’s pathways going out with a question mark. …This is like a funnel which widens, which is how I feel my mind widens and my thought process widens, and I want to know more. I want to ask questions, and I want to hear more.”[14] Robert was critical of his drawing skill, but his description could have come straight from a WHYY mission statement. Interestingly, Robert was not in the group that had received updates about WHYY stories or events. We found a mix of views about WHYY in both the groups that received updates and those who did not: Others in Robert’s control group said they rarely listened to the radio, and suggested a need for more community outreach. Some African American respondents doubted WHYY (which many just referred to as NPR) would connect effectively with other African Americans—even though they themselves listened regularly. In the group that received emails including WHYY stories and announcements, a few said they only knew WHYY television—Sesame Street, in particular. Others in the group associated WHYY with “more intellectual” conversations or commentary.[15]Overall, perceptions of WHYY were more positive than negative, though participants were less likely to mention its local coverage, and did not reference its community outreach.

Both groups had nuanced responses to a set of sample articles written as a result of community engagement efforts at WHYY and the Germantown Info Hub. The articles, one about the redevelopment initiative (by WHYY) and another about an initiative to open a new vegan grocery store (by the Info Hub) were presented without attribution to a newsroom. Overall, participants responded more favorably to the new set of stories than they had to stories presented in the earlier round –which had included a television story about a crime, but also a WHYY story about housing management in Germantown that predated any community outreach. Participants were more likely to say the stories in the second round of focus groups were aimed at residents.

While overall references to trustworthiness factors were more positive, participants did raise concerns in this round of discussions.In particular, they focused more on accuracy and respectful representation, and less on the perceived motives of the journalists. One participant saw WHYY’s story as “straight to the point” and appreciated that “they interviewed people who actually live in Germantown.”[16] Another participant appreciated historical context in the piece about white flight and capital flight, and their continued toll on the community.[17] In another group, a participant called the same story an “opinion-based article” that was essentially “their view of the history.”[18] Participants largely expressed satisfaction that the stories represented the community “where we are right now,”[19] but there was an acute sensitivity to even the slightest hint of stigma. In the Info Hub story about a new vegan grocery store, the reporters mentioned that EBT (electronic benefits transfer, commonly used for WIC and SNAP means-tested food benefits) was accepted. Some participants bristled at the mention of this early in the story:

Participant 5: Well I’m not sure why that’s so high up, so early in the article to talk about kinds of forms of payment they’ll accept. That seemed kind of strange to me. I would think that would be something at the end of the article … I’m like why did he mention it so early?

Participant 2: And you know, honestly and you look at a couple of things you’re saying, well, why? What are they trying to say?

Participant 5: Right, right. Right.

Participant 2: Everybody in Germantown is on EBT, you know, what are they trying to say?

Here, prominent reporting on the store’s desire to welcome EBT suggested to some participants the implication that all Germantowners were receiving government food benefits.

This was not the only time participants expressed ambivalence about solutions-oriented stories they felt were not unambiguously positive. Responding to WHYY’s story about redevelopment plans for a commercial corridor, some participants were displeased that the story detailed previously stalled plans:

I think the story gives a mixed message. I can’t figure out if it’s meant to be a positive, that something really good is about to happen to bring this magnificent spot back to life, because there’s so much focus on the negative, what happened to it. So, I understand they need to tell both sides of the story, but it’s a little bit of a mixed bag for me.[20]

The same participant raised a similar concern with the Info Hub story about the vegan grocer: “They seem to take a positive and find a way to introduce a little bit of negative whenever Germantown is mentioned.” This concerned her because of Germantown’s portrayal in the broader media: “We talked about that in the last session when it was, you know, a crime. You know, it’s like any criminal act that occurs within a 10-mile radius of Germantown becomes Germantown. So, it’s like you can’t just put out something really good and positive and let it be without introducing all these bad elements.”

Here, the standard reporting practice of seeking out multiple perspectives on an event, was seen through the prism of the neighborhood’s stigmatization. For residents subscribing to this viewpoint, even solutions journalism—that is, reporting on responses to social problems—can fall short of their desire to see counter-narratives. Groups like the Solutions Journalism Network are quick to distinguish solutions journalism from “good news” journalism and emphasize the need for rigor and a discussion of the limitations of a response to a problem. But for some Germantown residents, a history of press participation in stigmatizing narratives about the community has left them hungry for unambiguously positive reporting.

In the same group, we asked participants if they also saw a need for reporting about a neighborhood’s problems:

Participant 2: Sure, sure.

Participant 3: Absolutely.

Participant 2: You have to be informed. You can’t be in la-la-land.

One participant said she appreciated that a community paper from East Falls, a nearby neighborhood, had posted notices of break-ins or other crimes, and notices to look out for “criminals posing as repairmen.” For her, this was useful information, but another participant pointed out that it was different providing this kind of information about a less stigmatized neighborhood. “When you think of East Falls, you don’t automatically think crime,” the second participant said. This person argued that, because the dominant narrative about Germantown centered on crime, media should be responsible to “promote other aspects of the community.” Another participant agreed saying that, for most problems, there were people in the community trying to solve them. He wanted articles to feature more calls to action: “At the end of the article you can say, here’s how you get involved.” Repeatedly, participants outlined a role for community coverage that was more advocate for the community than distant, objective observer.

Community feedback on interventions

Despite these criticisms, participants responded very favorably when they learned about WHYY’s and the Germantown Info Hub’s outreach efforts. (Notably, almost no one said they had heard of these initiatives—not even the participants who had been getting email notices.) As one participant put it, “I think one of the biggest complaints against media is that they’re not serving their local communities. But when you’re making an active effort to go out and add the community and get their input on how the news is written, delivered, I think it’s great.”[21] Another participant in the same group agreed, replying that seeking community input showed the media being “sensitive for once,” and that this would help to ensure that “everyone is accurate.”[22]

Overall, participants believed these projects would help to improve trustworthiness factors, such as perceived accuracy, perceived motivations, and representation. But they also had a number of reservations about the limitations of the initiatives. Several participants suggested that they were unlikely to invest their energy in a project working to change narratives about the community if practical and concrete results did not come out of it. One participant was skeptical:

Things like storytelling, I don’t necessarily know that that would appeal to me. Maybe something more like job trainings … storytelling is cool, but job training … someone looking to get help on job placement or even something as simple as a GED isn’t necessarily looking towards storytelling.[23]

This skepticism was not universal. Another participant in their group suggested that the information gathered and shared by these projects could act as a kind of first step which could then be used to help inform “more concrete activity” that they would be more interested in participating in.[24]

Participants also offered feedback on some of the tactics the outreach projects used. Several people mentioned that when they saw groups “tabling” in public spaces—setting up a table with the project’s name and information and trying to interact with people there—it made them feel defensive:

Participant 3: When you see someone sitting at a table, what do you want from me?

Participant 5: Yeah, it’s like a sales thing.

Participant 3: It’s like, are you selling cookies? You know, do you want me to buy magazines? Maybe people find that a little bit off putting.[25]

One participant suggested that as an alternative, newsrooms could partner with groups that already have the trust of the community and join one of their meetings:

You know, one of these local groups is having their monthly meeting or whatever and, on the agenda, or just in the back of the room, ‘We’re tabling for Germantown Info Hub. Stop by and give your opinion on blah, blah, blah.’[26]

Another person said they had seen an announcement about the Germantown Info Hub tabling on social media, but “if you aren’t familiar with what the Info Hub is and what you mean by ‘tabling,’ a lot of people may not get that.”[27] She suggested that it may be more effective to offer more explanation and ask people to share opinions about a specific topic of concern in the community, such as gentrification.

Takeaways and recommendations

This study examined how residents of a neighborhood responded to two nascent efforts to build stronger relationships between their community and local media. For both the WHYY outreach efforts and the Germantown Info Hub, participants offered a combination of encouraging reflections, critiques that at times conflicted with one another, and important recommendations.

- In both cases, participants appreciated efforts that brought journalists and community members closer together. They suggested that, by spending more time hearing community perspectives, journalists would be motivated in ways that were more constructive to that community, and write coverage that was more accurate and respectful in its representation—all key trustworthiness factors.

- Many participants expressed a desire for news media to play a role that diverges from traditional journalism norms of objectivity. They expressed expectations that journalism for the community should champion the community and be selective in its criticism of neighborhoods with a history of stigmatizing coverage. Participants also shared a desire for news and information that offered pathways to action and concrete ways to address community issues.

- While both projects were in their pilot stages, both suffered from a lack of awareness among residents—including those who had seen some of the articles they produced. This suggests journalists cannot assume brand recognition based on news stories alone. Initiatives must find multiple channels to build relationships with communities over time.

- These and similar projects would benefit from recommendations offered by participants. In particular, rather than attempting direct cold outreach via tactics like tabling in public spaces, initiatives may have greater success collaborating with existing community organizations and making presentations or tabling at their gatherings. his requires a prior step of establishing shared expectations and trust between community groups and media initiatives. It also requires media outlets to understand the local context enough to know how organizations are perceived by different sectors of the community. But when approached with care, this process offers the initiatives a degree of trust by proxy. It also helps to strengthen what communication infrastructure theory (CIT) calls “storytelling network” ties between community groups and local media—something CIT argues is needed for healthy local communication infrastructures.

- Finally, though it may be challenging, such initiatives would do well to offer participants more actionable information and opportunities, beyond storytelling, in order to address the concrete needs of community members. Journalism projects fear being perceived as advocates—but, again, community organizations may offer a key. Community journalism projects can act as gatherers of information and as conveners of various groups that can work with residents to address local issues. Journalists cannot become service providers, but they can use the power and resources they have to connect residents to resources and to each other.

WHYY and the Germantown Info Hub both continue to grapple with the issues raised in these focus group discussions. WHYY seeks to apply lessons learned from its outreach efforts to neighborhoods across Philadelphia—an ambitious, but needed, challenge. Meanwhile, the Germantown Info Hub is moving from its pilot phase to a more regular project, with a dedicated project team that includes a community journalist and an organizer. We will continue to follow the project as it seeks to build upon these findings and to grow into a sustainable resource for the neighborhood.

[1] All names of participants have been changed or omitted.

[2] “Angela,” focus group discussion 7/16/18

[3] From July 2018 to March 2019

[4] These align with an adaptation of what Mayer, Davis, and Schoorman (1995) call “trustworthiness factors.”

[5] focus group discussion 7/17/19

[6] Participant G, focus group discussion 7/17/19

[7] Participant F, focus group discussion 7/17/19

[8] Participant D, focus group discussion 7/17/19

[9] Participant 6, focus group discussion 7/16/18071618

[10] focus group discussion 7/30/18

[11] focus group discussion 7/16/18

[12] Participant C, focus group discussion 7/17/19

[13] Participant C, focus group discussion 7/30/18

[14] “Robert,” focus group discussion 3/14/19

[15] focus group discussion 3/12/19

[16] Participant 2, focus group discussion 3/14/19

[17] focus group discussion 3/14/19

[18] Participant 1, focus group discussion 3/12/19

[19] Participant 3 focus group discussion 3/12/19

[20] Participant 3 focus group discussion 3/12/19

[21] Participant 4 focus group discussion 3/12/19

[22] Participant 2 focus group discussion 3/12/19

[23] Participant 1 focus group discussion 3/12/19

[24] focus group discussion 3/12/19

[25]focus group discussion 3/12/19

[26] focus group discussion 3/12/19

[27] Participant 3 focus group discussion 3/12/19

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.