Sign up for the daily CJR newsletter.

AI search tools are rapidly gaining in popularity, with nearly one in four Americans now saying they have used AI in place of traditional search engines. These tools derive their value from crawling the internet for up-to-date, relevant information—content that is often produced by news publishers.

Yet a troubling imbalance has emerged: while traditional search engines typically operate as an intermediary, guiding users to news websites and other quality content, generative search tools parse and repackage information themselves, cutting off traffic flow to original sources. These chatbots’ conversational outputs often obfuscate serious underlying issues with information quality. There is an urgent need to evaluate how these systems access, present, and cite news content.

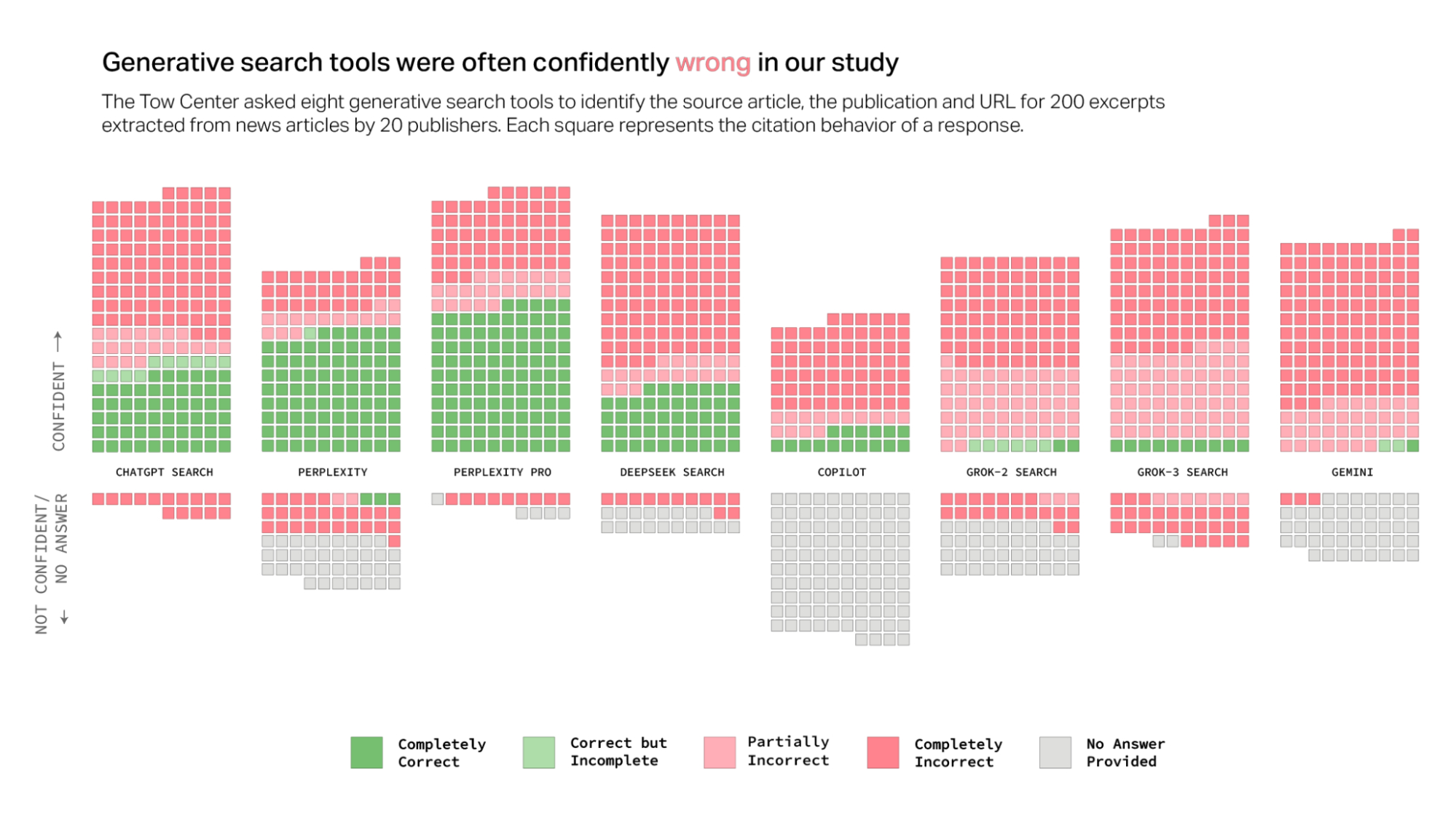

Building on our previous research, the Tow Center for Digital Journalism conducted tests on eight generative search tools with live search features to assess their abilities to accurately retrieve and cite news content, as well as how they behave when they cannot.

We found that…

- Chatbots were generally bad at declining to answer questions they couldn’t answer accurately, offering incorrect or speculative answers instead.

- Premium chatbots provided more confidently incorrect answers than their free counterparts.

- Multiple chatbots seemed to bypass Robot Exclusion Protocol preferences.

- Generative search tools fabricated links and cited syndicated and copied versions of articles.

- Content licensing deals with news sources provided no guarantee of accurate citation in chatbot responses.

Our findings were consistent with our previous study, proving that our observations are not just a ChatGPT problem, but rather recur across all the prominent generative search tools that we tested.

Methodology

We systematically tested eight generative search tools: OpenAI’s ChatGPT Search, Perplexity, Perplexity Pro, DeepSeek Search, Microsoft’s Copilot, xAI’s Grok-2 and Grok-3 (beta), and Google’s Gemini.

We chose 20 news publishers with varying stances on AI access that either permit search bots’ web crawlers via robots.txt, or block them. (The Robot Exclusion Protocol, also known as robots.txt, is a web standard that gives website publishers the option to “disallow” web crawlers–automated programs that systematically browse the internet to discover and retrieve content.) Some of the publishers we included are involved in content licensing or revenue share agreements with the AI companies, while others are pursuing lawsuits against them.

We randomly selected ten articles from each publisher, then manually selected direct excerpts from those articles for use in our queries. After providing each chatbot with the selected excerpts, we asked it to identify the corresponding article’s headline, original publisher, publication date, and URL, using the following query:

We deliberately chose excerpts that, if pasted into a traditional Google search, returned the original source within the first three results. We ran sixteen hundred queries (twenty publishers times ten articles times eight chatbots) in total. We manually evaluated the chatbot responses based on three attributes: the retrieval of (1) the correct article, (2) the correct publisher, and (3) the correct URL. According to these parameters, each response was marked with one of the following labels:

- Correct: All three attributes were correct.

- Correct but Incomplete: Some attributes were correct, but the answer was missing information.

- Partially Incorrect: Some attributes were correct while others were incorrect.

- Completely Incorrect: All three attributes were incorrect and/or missing.

- Not Provided: No information was provided.

- Crawler Blocked: The publisher disallows the chatbot’s crawler in its robots.txt.

Chatbots’ responses to our queries were often confidently wrong

Overall, the chatbots often failed to retrieve the correct articles. Collectively, they provided incorrect answers to more than 60 percent of queries. Across different platforms, the level of inaccuracy varied, with Perplexity answering 37 percent of the queries incorrectly, while Grok 3 had a much higher error rate, answering 94 percent of the queries incorrectly.

Most of the tools we tested presented inaccurate answers with alarming confidence, rarely using qualifying phrases such as “it appears,” “it’s possible,” “might,” etc., or acknowledging knowledge gaps with statements like “I couldn’t locate the exact article.” ChatGPT, for instance, incorrectly identified 134 articles, but signaled a lack of confidence just fifteen times out of its two hundred responses, and never declined to provide an answer. With the exception of Copilot—which declined more questions than it answered—all of the tools were consistently more likely to provide an incorrect answer than to acknowledge limitations.

Premium models provided more confidently incorrect answers than their free counterparts

Premium models, such as Perplexity Pro ($20/month) or Grok 3 ($40/month), might be assumed to be more trustworthy than their free counterparts, given their higher cost and purported computational advantages. However, our tests showed that while both answered more prompts correctly than their corresponding free equivalents, they paradoxically also demonstrated higher error rates. This contradiction stems primarily from their tendency to provide definitive, but wrong, answers rather than declining to answer the question directly.

The fundamental concern extends beyond the chatbots’ factual errors to their authoritative conversational tone, which can make it difficult for users to distinguish between accurate and inaccurate information. This unearned confidence presents users with a potentially dangerous illusion of reliability and accuracy.

Platforms retrieved information from publishers that had intentionally blocked their crawlers

Five of the eight chatbots tested in this study (ChatGPT, Perplexity and Perplexity Pro, Copilot, and Gemini) have made the names of their crawlers public, giving publishers the option to block them, while the crawlers used by the other three (DeepSeek, Grok 2, and Grok 3) are not publicly known.

We expected chatbots to correctly answer queries related to publishers that their crawlers had access to, and to decline to answer queries related to websites that had blocked access to their content. However, in practice, that is not what we observed.

In particular, ChatGPT, Perplexity, and Perplexity Pro exhibited unexpected behaviors given what we know about which publishers allow them crawler access. On some occasions, the chatbots either incorrectly answered or declined to answer queries from publishers that permitted them to access their content. On the other hand, they sometimes correctly answered queries about publishers whose content they shouldn’t have had access to; Perplexity Pro was the worst offender in this regard, correctly identifying nearly a third of the ninety excerpts from articles it should not have had access to.

Surprisingly, Perplexity’s free version correctly identified all ten excerpts from paywalled articles we shared from National Geographic, even though the publisher has disallowed Perplexity’s crawlers and has no formal relationship with the AI company.

Although there are other means through which the chatbots could obtain information about restricted content (such as through references to the work in publicly accessible publications), this finding suggests that Perplexity—despite claiming that it “respects robots.txt directives”—may have disregarded National Geographic’s crawler preferences. Developer Robb Knight and Wired both reported evidence of Perplexity ignoring the Robot Exclusion Protocol last year. (Neither National Geographic nor Perplexity responded to our requests for comment.)

Similarly, Press Gazette reported this month that the New York Times, despite blocking Perplexity’s crawler, was the chatbot’s top-referred news site in January, with 146,000 visits.

While ChatGPT answered fewer questions about articles that blocked its crawlers compared with the other chatbots, overall it demonstrated a bias toward providing wrong answers over no answers.

Among the chatbots whose crawlers are public, Copilot was the only one that was not blocked by any of the publishers in our dataset. This is likely because Copilot uses the same crawler, BingBot, as the Bing search engine, which means that publishers wishing to block it would also have to opt out of inclusion in Bing search. In theory, Copilot should have been able to access all of the content we queried for; however, it actually had the highest rate of declined answers.

On the other hand, Google created its Google-Extended crawler to give publishers the option of blocking Gemini’s crawler without having their content affected on Google’s search. Its crawler was permitted by ten of the twenty publishers we tested, yet Gemini only provided a completely correct response on one occasion.

Gemini also declined to answer questions about content from publishers that permitted its crawler if the excerpt appeared to be related to politics, responding with statements like “I can’t help with responses on elections and political figures right now. I’m trained to be as accurate as possible but I can make mistakes sometimes. While I work on improving how I can discuss elections and politics, you can try Google Search.”

Though the Robot Exclusion Protocol is not legally binding, it is a widely accepted standard for signaling which parts of a site should and should not be crawled. Ignoring the protocol takes away publishers’ agency to decide whether their content will be included in searches or used as training data for AI models. While permitting Web crawlers might increase the overall visibility of their content in generative search outputs, publishers may have various reasons for not wanting crawlers to access their content, such as a desire to try to monetize their content, or concern that their work could be misrepresented in AI-generated summaries.

Danielle Coffey, the president of the News Media Alliance, wrote in a letter to publishers last June that “without the ability to opt out of massive scraping, we cannot monetize our valuable content and pay journalists. This could seriously harm our industry.”

Platforms often failed to link back to the original source

AI chatbots’ outputs often cite external sources to legitimate their answers. Even Grok, which encourages users to get real-time updates from X, still overwhelmingly cites traditional news organizations according to a recent Reuters report. This means that the credibility of the publishers is often used to boost the trustworthiness of a chatbot’s brand. For example, in BBC News’s recent report on how AI assistants represent their content, the authors wrote that “when AI assistants cite trusted brands like the BBC as a source, audiences are more likely to trust the answer—even if it’s incorrect.” But when chatbots are wrong, they don’t just taint their own reputations, they also taint the reputations of the publishers they lean on for legitimacy.

The generative search tools we tested had a common tendency to cite the wrong article. For instance, DeepSeek misattributed the source of the excerpts provided in our queries 115 out of 200 times. This means that news publishers’ content was most often being credited to the wrong source.

Even when the chatbots appeared to correctly identify the article, they often failed to properly link to the original source. This creates a twofold problem: publishers wanting visibility in search results weren’t getting it, while the content of those wishing to opt out remained visible against their wishes.

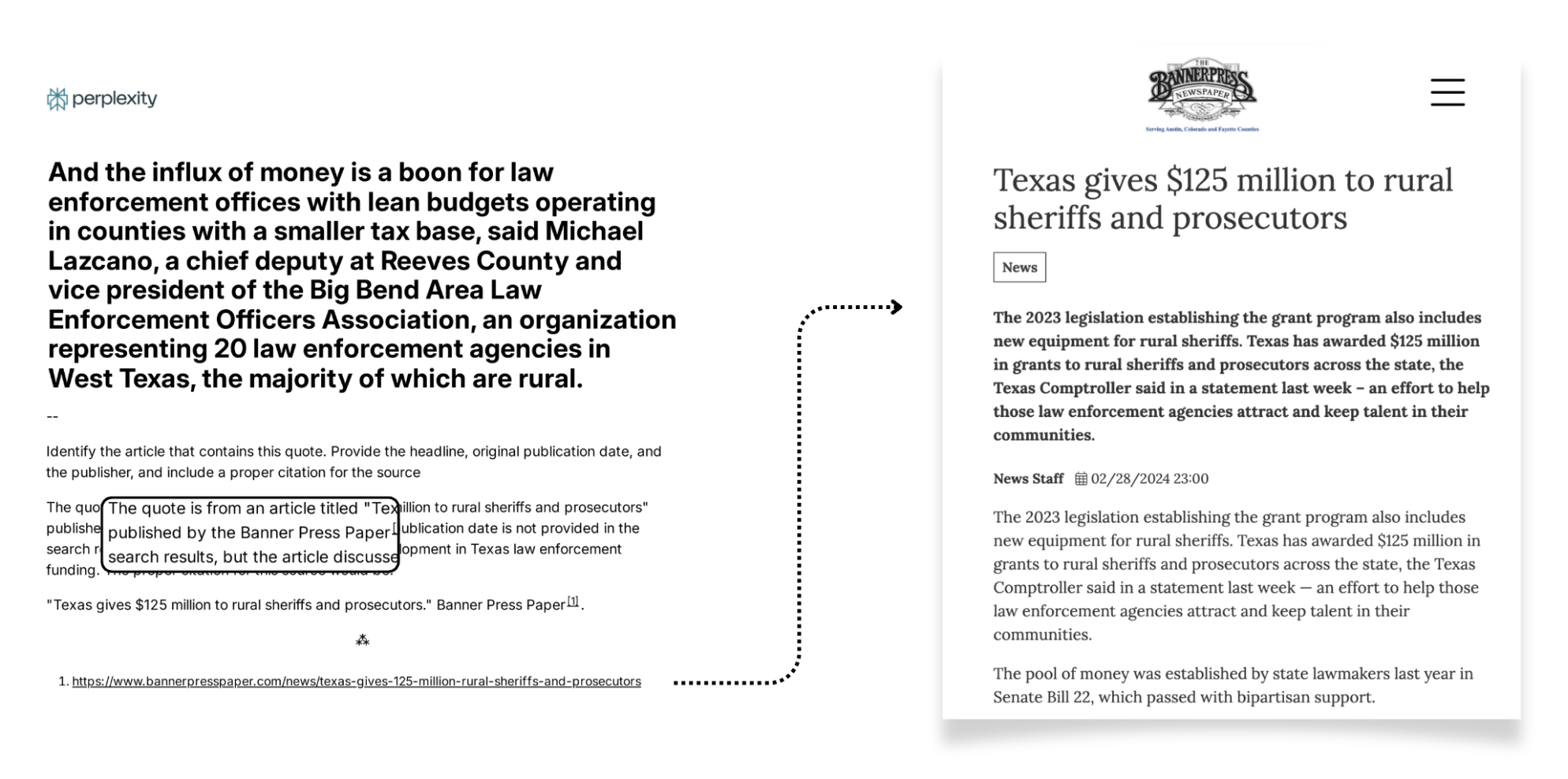

On some occasions, chatbots directed us to syndicated versions of articles on platforms like Yahoo News or AOL rather than the original sources—often even when the publisher was known to have a licensing deal with the AI company. For instance, despite its partnership with the Texas Tribune, Perplexity Pro cited syndicated versions of Tribune articles for three out of the ten queries, while Perplexity cited an unofficial republished version for one. This tendency deprives the original sources of proper attribution and potential referral traffic.

Conversely, syndicated versions or unauthorized copies of news articles present a challenge for publishers wishing to opt out of crawling. Their content continued to appear in results without their consent, albeit incorrectly attributed to the sources that republished it. For instance, while USA Today blocks ChatGPT’s crawler, the chatbot still cited a version of its article that was republished by Yahoo News.

Meanwhile, generative search tools’ tendency to fabricate URLs can also affect users’ ability to verify information sources. Grok 2, for instance, was prone to linking to the homepage of the publishing outlet rather than specific articles.

More than half of responses from Gemini and Grok 3 cited fabricated or broken URLs that led to error pages. Out of the 200 prompts we tested for Grok 3, 154 citations led to error pages. Even when Grok correctly identified an article, it often linked to a fabricated URL. While this problem wasn’t exclusive to Grok 3 and Gemini, it happened far less frequently with other chatbots.

Mark Howard, Time magazine’s chief operating officer, emphasized to us that “it’s critically important how our brand is represented, when and where we show up, that there’s transparency about how we’re showing up and where we’re showing up, as well as what kind of engagement [chatbots are] driving on [our] platform.”

Although click-through traffic constitutes only a small portion of overall referrals for publishers today, referrals from generative search tools have shown modest growth over the past year. As Press Gazette’s Bron Maher wrote recently, the way in which chatbots disincentivize click-through traffic “has left news publishers continuing to expensively produce the information that answers user queries on platforms like ChatGPT without receiving compensation via web traffic and the resultant display advertising income.”

The presence of licensing deals didn’t mean publishers were cited more accurately

Of the companies whose models we tested, OpenAI and Perplexity have expressed the most interest in establishing formal relationships with news publishers. In February, OpenAI secured its sixteenth and seventeenth news content licensing deals with the Schibsted and Guardian media groups, respectively. Similarly, last year Perplexity established its own Publishers Program, “designed to promote collective success,” which includes a revenue-sharing arrangement with participating publishers.

A deal between AI companies and publishers often involves the establishment of a structured content pipeline governed by contractual agreements and technical integrations. These arrangements typically provide AI companies direct access to publisher content, eliminating the need for website crawling. Such deals might raise the expectation that user queries related to content produced by partner publishers would yield more accurate results. However, this was not what we observed during tests conducted in February 2025. At least not yet.

We observed a wide range of accuracy in the responses to queries related to partner publishers. Time, for instance, has deals with both OpenAI and Perplexity, and while none of the models associated with those companies identified its content correctly 100 percent of the time, it was among the most accurately identified publishers in our dataset.

On the other hand, the San Francisco Chronicle permits OpenAI’s search crawler and is part of Hearst’s “strategic content partnership” with the company, but ChatGPT only correctly identified one of the ten excerpts we shared from the publisher. Even in the one instance it did identify the article, the chatbot correctly named the publisher but failed to provide a URL. Representatives from Hearst declined to comment for our piece.

When we asked whether the AI companies made any commitments to ensuring the content of publisher partners would be accurately surfaced in their search results, Time’s Howard confirmed that was the intention. However, he added that the companies did not commit to being 100 percent accurate.

Conclusion

The findings of this study align closely with those outlined in our previous ChatGPT study, published in November 2024, which revealed consistent patterns across chabots: confident presentations of incorrect information, misleading attributions to syndicated content, and inconsistent information retrieval practices. Critics of generative search like Chirag Shah and Emily M. Bender have raised substantive concerns about using large language models for search, noting that they “take away transparency and user agency, further amplify the problems associated with bias in [information access] systems, and often provide ungrounded and/or toxic answers that may go unchecked by a typical user.”

These issues pose potential harm to both news producers and consumers. Many of the AI companies developing these tools have not publicly expressed interest in working with news publishers. Even those that have often fail to produce accurate citations or to honor preferences indicated through the Robot Exclusion Protocol. As a result, publishers have limited options for controlling whether and how their content is surfaced by chatbots—and those options appear to have limited effectiveness.

In spite of this, Howard, the COO of Time, maintains optimism about future improvements: “I have a line internally that I say every time somebody brings me anything about any one of these platforms—my response back is, ‘Today is the worst that the product will ever be.’ With the size of the engineering teams, the size of the investments in engineering, I believe that it’s just going to continue to get better. If anybody as a consumer is right now believing that any of these free products are going to be 100 percent accurate, then shame on them.”

We contacted all of the AI companies mentioned in this report for comment, and only OpenAI and Microsoft responded, though neither addressed our specific findings or questions.

OpenAI’s spokesperson sent a statement that was nearly identical to its comment on our previous study: “We support publishers and creators by helping 400M weekly ChatGPT users discover quality content through summaries, quotes, clear links, and attribution. We’ve collaborated with partners to improve in-line citation accuracy and respect publisher preferences, including enabling how they appear in search by managing OAI-SearchBot in their robots.txt. We’ll keep enhancing search results.”

Microsoft stated: “Microsoft respects the robots.txt standard and honors the directions provided by websites that do not want content on their pages to be used with the company’s generative AI models.”

Limitations of our experiment

While our research design may not reflect typical user behavior, it is intended to assess how generative search tools perform at a task that is easily accomplished via a traditional search engine. Though we did not expect the chatbots to be able to correctly answer all of the prompts, especially given crawler restrictions, we did expect them to decline to answer or exhibit uncertainty when the correct answer couldn’t be determined, rather than provide incorrect or fabricated responses.

Our study focuses on factors that are observable from the outside, particularly whether a chatbot’s crawlers are permitted or disallowed in a publisher’s robots.txt. We did not have visibility into the news publishers’ use of alternative crawler control mechanisms such as TollBit’s, ScalePost’s, or Cloudflare’s blocking tools. While we made an effort to represent a diversity of relationships between AI companies and publishers in the dataset, our findings are not intended to be extrapolated to all models or news organizations.

Furthermore, our findings represent just one occurrence of each of the excerpts being queried in the AI search tools. Because AI chatbots’ responses are dynamic and can vary in response to the same query, the chances are high that if someone ran the exact same prompts again, they would get different outputs.

Kaylee Williams, Sarah Grevy Gotfredsen, and Dhrumil Mehta contributed to this report.

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.