Sign up for the daily CJR newsletter.

The new media networks that rely on user-generated content—primarily Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube— are both a gift of unlimited material to research-savvy reporters on deadline, and a minefield of potential mistakes that could get a clumsy, naive, or hasty journalist fired in a heartbeat.

It’s important that journalism students and aspiring reporters learn how to verify information generated by amateurs who might be eyewitnesses to a huge story on the one hand and might be panicky and underinformed—or even malicious—on the other. Below is a class-length lecture on verifying digital information prepared by Tow Center fellow Priyanjana Bengani and compiled from publicly available sources. The presentation is available for distribution and download under the Creative Commons license.

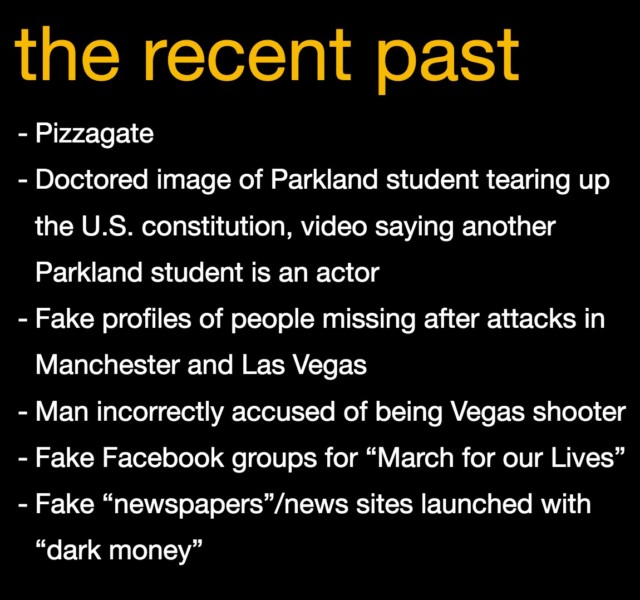

Included are a series of examples of fake news, a number of exercises increasing in difficulty over the course of the class—all solvable using nothing more than an internet connection and Google—, and a list of tools for exploring the details, visible and invisible, of the internet’s endlessly fascinating and newsworthy flotsam.

Excerpts from the presentation and advice for journalists are below; the entire slideshow and notes can be downloaded at the bottom of the page or streamed through Google Slides. Story links for examples can be found in the “speaker notes” section.

—Sam Thielman, Tow Center Editor

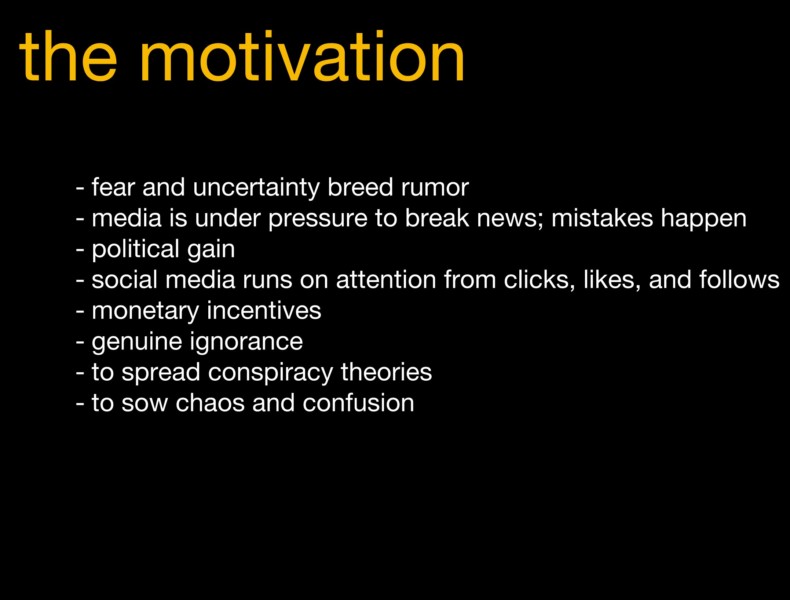

Life online has gotten very weird in the last few years, with trolling campaigns, commercial spam, activism, and old-fashioned meanness doing battle with real-time news for viewer attention. Often the worst lies have a grain of truth to them, and more often still, those lies are spread not as part of an organized conspiracy but simply out of a desire for public attention.

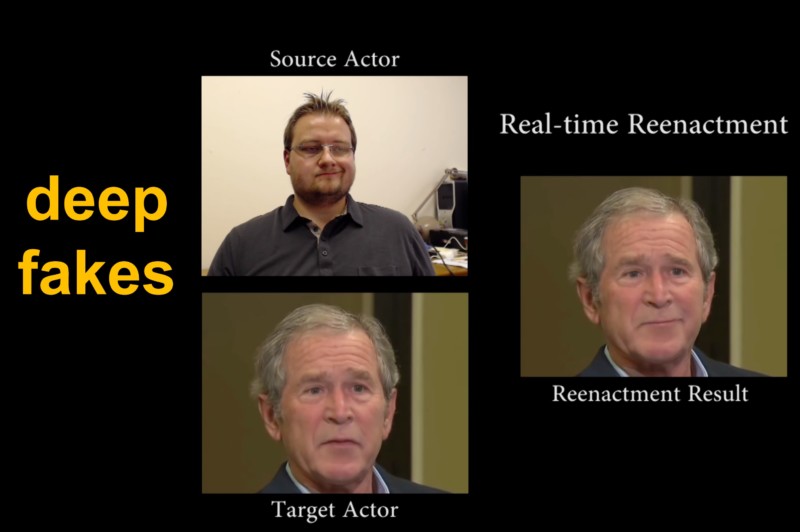

BuzzFeed’s deepfake video of “President Obama”—convincingly voiced by Get Out writer-director Jordan Peele—is both a comedy short and a PSA about the problem of misinformation online: Seeing is not always believing.

Though the focus tends to be on sophisticated fakery, one of the most common and simple tactics is mislabeling. In the example above, from a deceptive Facebook post, the woman promoted to the user’s network of more than 40,000 followers as “Emma Gonzales”—the Parkland shooting survivor and anti-gun activist—breaking into a car is actually pop singer Britney Spears.

Social media coverage of news about emergencies is perhaps the most fertile ground for fakes, mistakes, and conspiracies to take root. Reporters must break news quickly, and eyewitness accounts, though they are prized above any other kind of information, are often spotty and affected by the uncertainty of the moment. Bystanders—and journalists in the thick of it—may make mistakes under the twin pressures of the emergency event and the scrutiny of the public.

As photo analysis technology advances, computers are able to spontaneously generate wireframe images of a user’s face in time to superimpose it on a live video—that’s what you see when a filter on Instagram gives you rabbit ears or makes your eyes big. It can also change your face to look like another person’s entirely, and that technology is advancing disturbingly quickly. Tow Center fellow Nick Diakopoulos has said that the progress offers journalists an opportunity to reposition themselves as people with a professional investment in trustworthiness to whom readers can look in uncertain times.

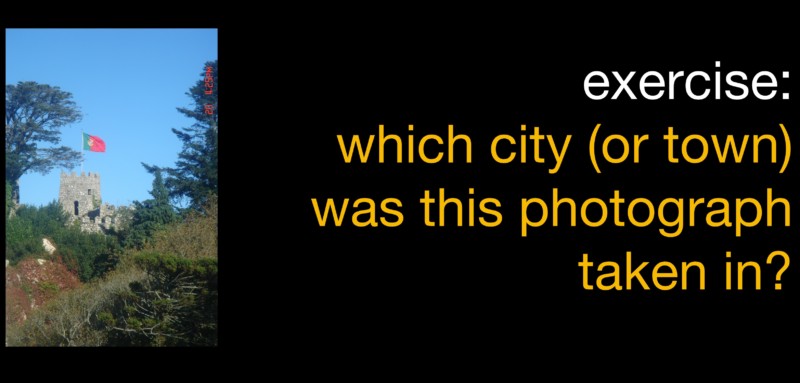

Photos on social media don’t have EXIF metadata containing the date, camera type, time, and location information stored by most cameras and camera phones within the original image file. If a journalist can obtain the original image from the person who first uploaded it to social media, that information can be extracted either with the “get info” function on a Mac running a recent OS, or by uploading the image to a photo analysis site like FotoForensics (which is free). But even without the metadata, some information can be gleaned from the photo: Identifying the flag is fairly easy; a Google Image search of the nation’s name and the words “flag” and “castle” will bring up an image of this building in Sintra, Portugal very quickly.

If the appearance of the image itself is part of the question—say, whether it was posted recently or a while ago—Google’s Vision API can find instances of the photo at different resolutions and cropped in different ways across the web.

Some references Bengani and the Tow Center for Digital Journalism recommend:

- The Verification Handbook

- Bellingcat

- Jeffrey’s Image Metadata Viewer

- The Google Vision API

- Camopedia

- The Department of Homeland Security’s Vulnerability Summary bulletins

Click here to open the above in Google Slides if you would like to download the entire presentation. All material is available for use under Creative Commons license CC BY 2.0.

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.