Sign up for The Media Today, CJR’s daily newsletter.

One of the major journalism themes of 2025 is emerging: the role, and importance, of nontraditional or journalism-adjacent information providers. From influencer/creator/independent news producers to AI-generated content to civic media, defining who qualifies as a journalist is as difficult as it has ever been. This idea was front and center at the recent Knight Media Forum, where several discussions showed clearly that the idea of what qualifies as journalism is expanding—largely out of necessity, but also as an overdue acknowledgment of the fact that sometimes the most vital local journalism comes not from a newspaper but from a newsletter or Facebook group.

There is now a broader willingness to consider—or, perhaps more accurately, to see—the myriad other ways that people share and receive important local information and news. The further we get into the local journalism crisis, the more we’re forced to confront the fact that sustainable local journalism cannot, and will not, look as it did in the past. The rise of the newsfluencer is the latest iteration of this message.

This does not mean that journalists or journalism should become obsolete. Elsewhere I’ve suggested that we move from a news desert metaphor to that of an information ocean, in which journalists serve as lifeboats and beacons, lifting us above the noise and pointing us toward trustworthy, factual information. Where local journalism thrives, those lifeboats and beacons are readily available; where it does not, people swim and bob in all directions, awash in triviality and misinformation—many of them longing for real news.

A 2022 study by UT-Austin’s Center for Media Engagement found that nearly half of people surveyed who live in areas defined as news deserts disagreed with that characterization, saying they were able to find news and information about their communities from alternative sources like Facebook groups and chambers of commerce. This finding was confirmed in an early 2025 survey by the American Communities Project, in which 44 percent of respondents said they “learn more about what’s happening in my community on social media than through the news.”

What do these nontraditional news and information sources look like? And how might they be made even more visible to those who have to swim in information oceans without lifeboats or beacons to guide them?

For the past several months I’ve been looking closely at North Carolina’s local information and news landscape. One of the reasons I chose to begin what will eventually be a nationwide effort in North Carolina is that the state is home to some of the most innovative and successful journalism support efforts in the country (other such states include New Jersey and Colorado). In addition, its 100 counties contain tremendous variety in terms of terrain and demographics—two variables known to affect people’s access to local news and all of the services and affordances associated with it.

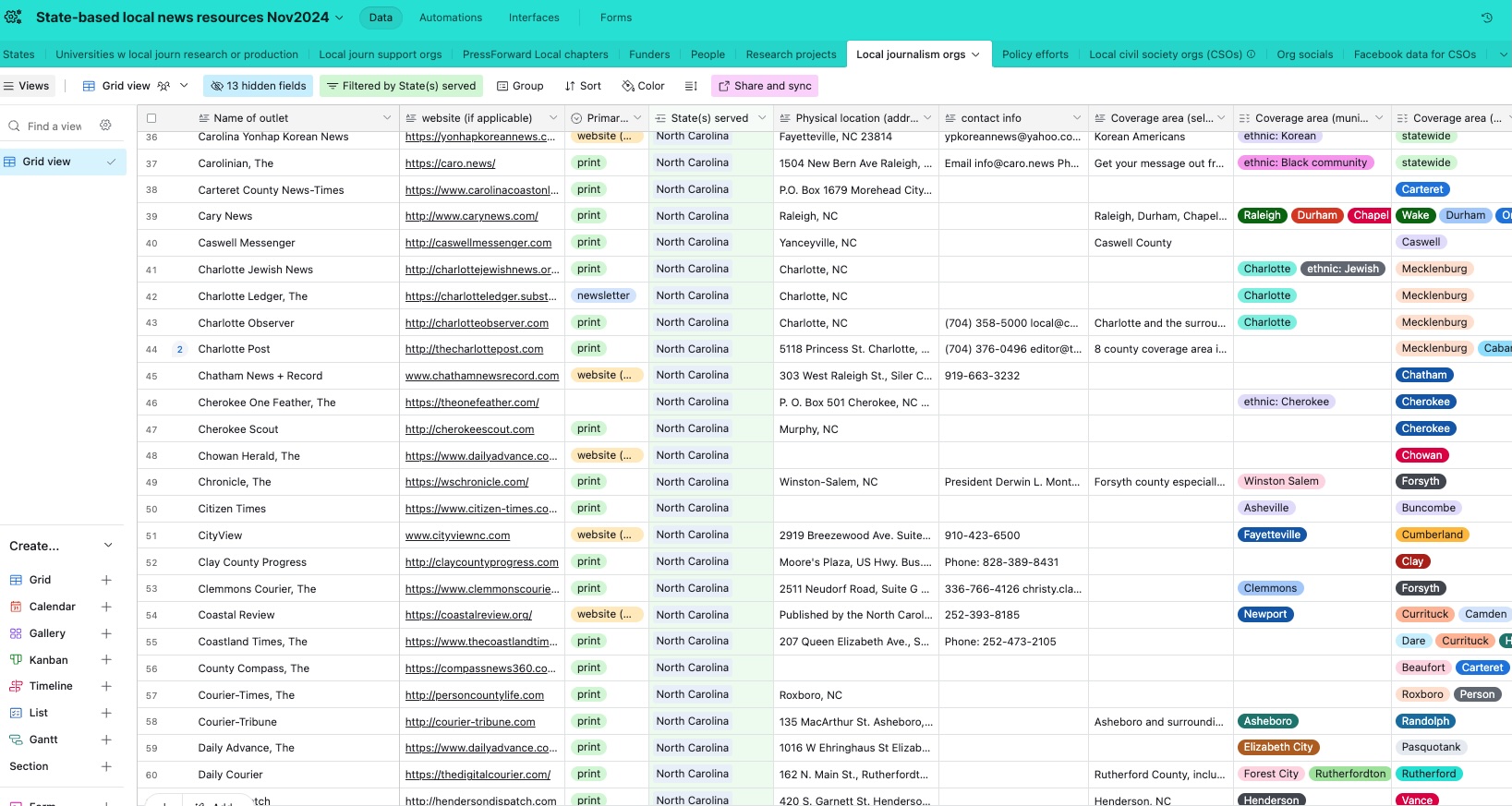

So far I have identified 241 local news providers and 480 civil society organizations (CSOs) that serve communities in North Carolina. For each I am gathering relevant information about their operations, including service/coverage areas, social media presence, and sources of funding. These data will provide the foundation for an online registry that can produce analyses and be used by the public and industry. They will also inform a taxonomy of the members of local news ecosystems across the state. Eventually (soon, I promise!) we will have a website where these databases will be live (see below for screenshots of the journalism outlet and civil society organization bases).

A great example of a local NC newsfluencer is Rob Robinson, who made an eloquent and very watchable plea to the Asheville local zoning board to change the rules around the land on which an Arby’s had stood vacant for roughly a decade. Blue Ridge Public Radio—itself a vital source for public information, especially during Hurricane Helene—reported that after Robinson’s YouTube video gained more than 4,000 views, the Asheville City Council in early March voted to change the zoning laws along the lines recommended by Robinson, and publicly gave Robinson credit “for getting community members excited about zoning reform.”

Likewise, and as many before me have pointed out, CSOs often serve as crucial providers of local information and news. For example, during the pandemic, the NC Cambodian Culture Center’s community bulletin subpage posted online videos made by the City of Greensboro showing local health notices that were printed and voiced over in Khmer—a language spoken by North Carolinians with Cambodian, Laotian, or Vietnamese heritage. Because the Cambodian Culture Center is a trusted partner of the community whose members communicate with it frequently, they were able to reach people in a way that the city government, or a mainstream local news outlet, could not.

The registry’s aim is to surface these civil society organizations—as well as information about traditional and nontraditional local news providers—and bring this information together into one place, to encourage collaboration in service of communities.

We are also working on a data visualization element that will render content produced by news outlets and CSOs visible by locations covered. My colleague at the Brown Institute, Michael Krisch, along with his collaborator Marianne Simone Aubin Le Quere, who is a PhD candidate at Cornell Tech, have demonstrated what this would look like with articles from local news outlets Border Belt Independent and Carolina Peacemaker, and local CSO the North Carolina Coastal Federation; in the image below each organization’s content is represented by a different color dot, and the areas where they overlap suggest geographic spaces that might be ripe for collaboration.

Along with other analyses that this work will provide, the ability to see clearly which geographies are covered, and by whom, opens the door to a better-informed ecosystem and, hopefully, greater collaboration among those who are trying to meet critical information needs.

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.