Sign up for The Media Today, CJR’s daily newsletter.

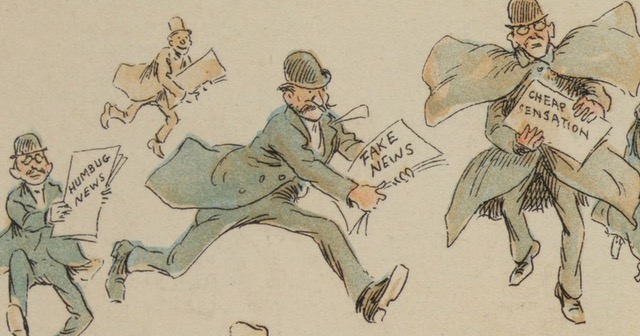

It is now over a decade since the label “pink slime journalism” was first applied to the proliferation of low-cost, low-quality local news content oozing across the United States. During this time, pink slime producers (such as Metric Media, which operates a network of more than 1,200 websites) have become synonymous with hyper-partisan content and loose ethical standards – as detailed in a new report by the Tow Center for Digital Journalism at Columbia University.

These sites are familiar yet misleading – masquerading as the digital equivalent of traditional, well-trusted, locally-based newspapers, but actually promoting political, ideological, and commercial interests in strategically-significant locations. From boosting political candidates to providing positive publicity for under-fire corporations, pink slime publications seek to exploit audience assumptions about the type of content published by a “news” organization; in particular, the expectation that journalism (and local journalism, in particular) is motivated by public interest and newsworthiness, not commercial deals or hidden political agendas.

Such a bastardization of the journalistic process – comparable to filling a news organization with the fluorescent pink meat paste used by food manufacturers – seems like a novel phenomenon. After all, many of the trends examined by the Tow Center rely on relatively recent technology, including advances in automation and audience microtargeting on social platforms. Churning out “pseudo-journalism” – and pushing it out to the right people – has never been easier, faster, or cheaper.

And yet, for all that this process is now digitally-driven, the strategy of misleading audiences using the media is older than the United States itself. Indeed, the so-called “Founding Fathers” would have been far more familiar with the commercially-compromised, politically-patronized “pseudo-news organizations” described in the Tow Center report than any of the venerable institutions now considered bastions of the free press. Furthermore, this first generation of American leaders would not be the last to manipulate the media to advance their own interests – whether that be personal advancement, or a genuine belief that such actions were necessary to save the republic.

PRESS AND PROPAGANDA

The American Revolution was the first of many episodes from U.S. history in which the press – and the popular formats and channels through which news is communicated to the public – was used to spread disinformation and legitimize falsehoods. The similarities between past and present are numerous: from politicians producing fake newspapers to outmaneuver their rivals, to reporters lying about their location in order to produce “local”(ish) content, to billionaires buying news outlets to create their personal propaganda organs. Today, such behavior undermines the notion that journalism is an integral part of a healthy democratic society – compounding already daunting challenges facing every media organization and further eroding public trust in their work.

The evolution of the journalist from political propagandist to professional watchdog is the central theme of U.S. media history. According to this narrative, the press gradually freed itself from dependence on (and subservience to) politicians and their parties by securing new sources of revenue, including advertising and subscriptions.1 For example, Maria Petrova, “Newspapers and Parties: How Advertising Revenues Created an Independent Press.” The American Political Science Review 105, no. 4 (2011), 790–808. As the legendary newspaper editor and publisher Joseph Pulitzer once quipped, “Circulation means advertising, and advertising means money, and money means independence.”2 Quoted in Paul Starr, The Creation of the Media: Political Origins of Modern Communications (New York: Basic Books, 2004), 257.

Statue of Thomas Jefferson (funded by Joseph Pulitzer) in front of Pulitzer Hall, home of Columbia University’s School of Journalism (Columbia Daily Spectator)

Pink slime journalism seeks to exploit comparatively modern assumptions about this “independence,” and the other values that guide credible news outlets – not least the belief that in America “the press swapped partisan loyalty for a new compact – that journalism would harbor no hidden agenda.”3 Bill Kovach & Tom Rosenstiel, The Elements of Journalism: What Newspeople Should Know and the Public Should Expect, 3rd ed. (New York: Three Rivers Press, 2014), 148. While the reader of a revolutionary-era newspaper may have expected partisanship, financially-compromised proprietors, and the occasional “hoax,” the professionalization of the press was supposed to herald a brave new dawn – one in which fearless reporting and fiercely-guarded editorial independence was paramount.4 Michael Schudson, Why Journalism Still Matters, (Cambridge, England: Polity Press, 2018), 51; Andie Tucher, Not Exactly Lying: Fake News and Fake Journalism in American History (New York: Columbia University Press, 2022), 7. That’s why today’s pink slime publications make little or no effort to communicate the connections between their content, their funding, and their purpose; concealing their true nature is crucial to any ability they might have to influence public opinion.

FOUNDING FORGERS

Pink slime journalism’s lack of transparency is one reason why it is so reviled across the mainstream media community. However, as Andie Tucher, a historian at Columbia University’s School of Journalism, outlines in her recent book, this type of “deceptive practice” has been going on for hundreds of years. Tucher uses the term “fake journalism” to describe the use of “some kind of authentic or authentic-seeming perch or platform” to “present false information or heavily partisan opinion or propaganda in a form specifically crafted to look or sound like ‘real’ independent journalism rooted in impartial investigation and rigorous verification.”5 Tucher, Not Exactly Lying, 6. Online pink slime publications are a modern iteration of this tactic – harnessing new technologies to produce a plausible imitation of local news content that can be micro-targeted at specific groups or spread far and wide.

The fact that political actors are bankrolling so many of these operations is also unsurprising. Today, a tenet of American democratic life is that the press is independent of politicians and their parties. Journalists scrutinize these people, they do not promote their interests in return for financial support. Freedom from (direct) political interference is enshrined in the First Amendment (“Congress shall make no law…abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press”), a statement that implicitly rejected the “Old World” of censorship and subservient publishers scrabbling around for state subsidies.

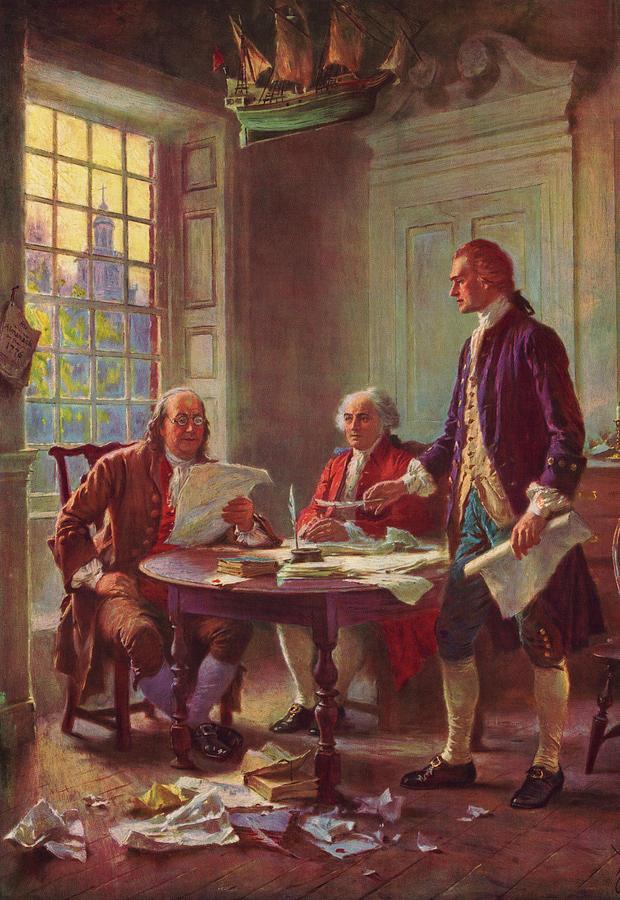

Instead, “Founding Fathers” like Benjamin Franklin and Thomas Jefferson hoped that the nation’s “free” press would be a unifying force – forging civic connections and informing democratic participation, while promoting the values and institutions that would make the United States truly exceptional. In 1787, Jefferson even claimed that with “the basis of our governments being the opinion of the people, the very first object should be to keep that right; and were it left to me to decide whether we should have a government without newspapers, or newspapers without a government, I should not hesitate a moment to prefer the latter.”

Thomas Jefferson, Benjamin Franklin, and John Adams depicted in “Writing the Declaration of Independence, 1776,” a painting by J.L.G. Ferris. https://www.loc.gov/item/2002719535/

The reality never matched the rhetoric. Utopian proclamations were replaced by disillusionment as growing political polarization was amplified to the public by newspapers still dependent on elite patronage. By 1807, (now President) Jefferson – the subject of countless personal attacks and the occasional scandalous exposé – complained that “nothing can now be believed which is seen in a newspaper. Truth itself becomes suspicious by being put into that polluted vehicle.” George Washington, Alexander Hamilton, and others shared similar complaints about the American press deepening national divisions through its inaccuracies, personal attacks, and hyper-partisan content – all while making the United States appear weak (“on the very verge of disunion,” according to Washington) to the rest of the world.

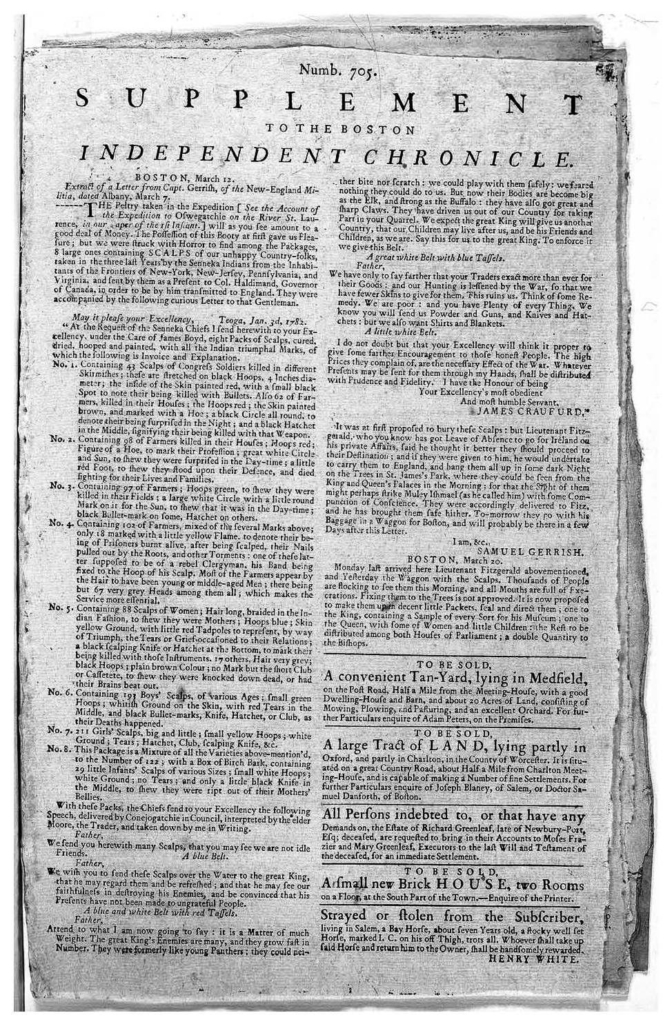

George Washington was not alone in fretting about bad publicity. Two of the earliest instances of “fake journalism” in U.S. history were committed by “Founding Fathers” in order to boost American interests overseas. The first was undertaken by Benjamin Franklin, the pioneering publisher and master propagandist, among many other distinctions. In 1782, Franklin (then based in France) sought to stoke public outrage against the British forces fighting in the Revolutionary War. His plan was to shock British and European audiences by using a (then) novel deception: the fake newspaper.

“Supplement to the Boston Independent Chronicle” appeared to be an unremarkable edition of one of Boston’s best-known newspapers; a print copy transported back across the Atlantic by some unknown individual. The document seemed authentic; from accurate dating, numbering, and text layout, to the inclusion of adverts and even information about a missing horse. However, the most notable feature in the newspaper was a shocking account of large-scale atrocities committed by Native American tribes allied to the British, including mass scalping of women and children. Indeed, the newspaper noted that a bag of these scalps was due to be sent back to England as grisly proof of these deeds.

However, the newspaper was a fake. Printed on Franklin’s own press and with no connection to the Independent Chronicle, it was designed to spread anti-British disinformation among its target audience. Franklin, who undertook many similar “hoaxes” (some more satirical than others) throughout his long life, cannily exploited the increased credibility afforded to a story when placed in the familiar template of a news publication – a tactic that remains a staple of the disinformation playbook.6 In his biography, Walter Isaacson describes Franklin as “America’s first great-image maker and public relations master.” As Isaacson notes, Franklin “wrote his first hoax at 16 and the last on his deathbed; he misled his employer Samuel Keimer when scheming to start a newspaper; he perfected indirection as a conversational artifice; and he utilized the appearance of virtue as well as its reality.” Walter Isaacson, Benjamin Franklin: An American Life (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2003), 328, 488. Similarly, Franklin attempted to increase the reach and impact of his work by targeting established news sources – in this case, sending copies of his publication to British newspaper editors in the hope that they would amplify and legitimize its contents. Of course, the Native Americans that Franklin tarnished with these fictional atrocities were collateral damage; just one of many examples from this period in which false allegations were made against tribes and Black people (free and enslaved) to boost white Patriotic zeal.7 For more examples see Gregory Evans Dowd, Groundless: Rumors, Legends, and Hoaxes on the Early American Frontier (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2015); Robert G. Parkinson, Thirteen Clocks: How Race United the Colonies and Made the Declaration of Independence (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2021).

Franklin was not the only “Founding Father” attempting media-based deceptions in Europe. In 1784, a French officer “lately returned from service and residence in the U.S. of America” had his letter published in the Gazette de Leyde, a “much read and respected” publication on the continent – indeed, “the only one I know in Europe which merits respect,” according to the author. The writer bemoaned “all this misinformation” about America that he had read in European newspapers, claiming that these falsehoods could be “traced” to fake news cunningly spread by the British. However, all was not what it seemed. The authoring “French officer” was actually Thomas Jefferson, who forwarded his letter to leading European newspapers in order to promote American interests. This “sock puppet” scam – perpetrated by the man whose statue stands outside the Columbia University School of Journalism – exemplifies how many of the press’ early champions mixed high-minded words with cunning action.

“KEEPING THE PUBLIC MIND RIGHT”

However, America’s founders still believed that the character and “liberty” of their press was truly exceptional. Franklin and Jefferson had lived in Europe and seen firsthand the impact of state censorship and coercion. Even in Britain, where royal sovereignty was more equally balanced by legislative power, governments throughout the 18th century implemented repressive measures designed to retard the popularity of the press. For example, taxes on newspapers increased by 800% between 1712 and 1815. This financial squeeze – combined with draconian libel laws and state subsidies for favored publications – created an environment in which publishers knew that criticizing the powerful came at a cost.

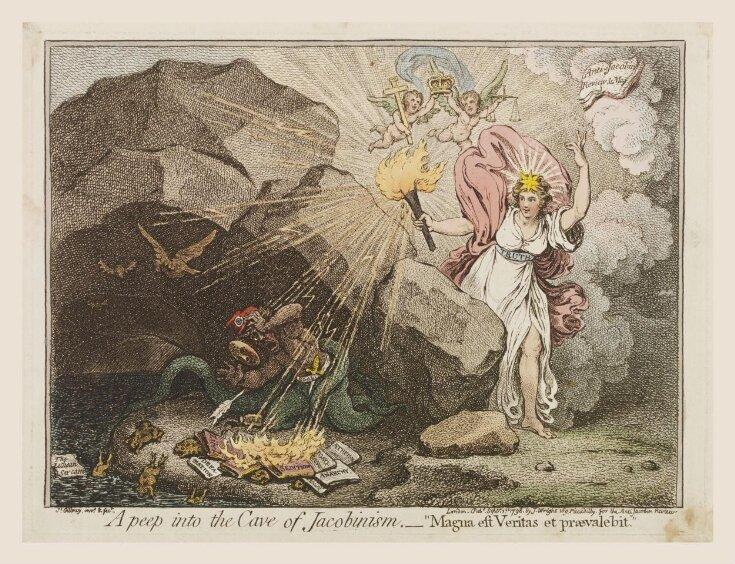

By the turn of the 19th century, the British government launched its own publications in response to growing anxiety (especially among the conservative elite) that newspapers were fueling insurrectionary sentiment among the public, just as they had done in America and France. In addition to cracking down on newspapers deemed “radical,” the government launched outlets to steer public opinion in line with its reactionary agenda. New titles, including The Sun (no, not that one) and the Anti-Jacobin, were bankrolled by the state to attack individuals and organizations deemed a threat to the status quo – a policy described by one minister as “keeping the public Mind right…”8 Diary of George Canning, October 18-21, 1797, quoted in John Ehrmann, The Younger Pitt (Vol. 3): The Consuming Struggle (London: Constable, 1996), 111.

The British state also purchased the support of established titles and individual journalists. Political patronage – common practice for proprietors and editors in this period – could entangle even the loudest champions of press freedom, such as writer William Combe, who once boasted that “not all the power of ministers, or all the wealth of the Treasury, would tempt or bribe me.”9 Arthur Aspinall, Politics and the Press, c.1780-1850 (London: Home & Van Thal, 1949), 165. By 1792, Combe was receiving a secret state subsidy of £200 per annum to churn out pro-government pieces.

By contrast, American newspapers in this period were comparatively independent from government institutions (although not necessarily from individual politicians and their parties) and even benefited from policies designed to grow the news ecosystem. For example, the Post Office Act of 1792 boosted both the number of publications across the United States and their readerships.10 See Richard R. John, Spreading the News: The American Postal System from Franklin to Morse (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard Univ. Press, 1998). America soon became the most developed and dynamic newspaper market in the world, buoyed by rising literacy rates, enhanced communications infrastructure, expanding transport networks, and advanced technology.

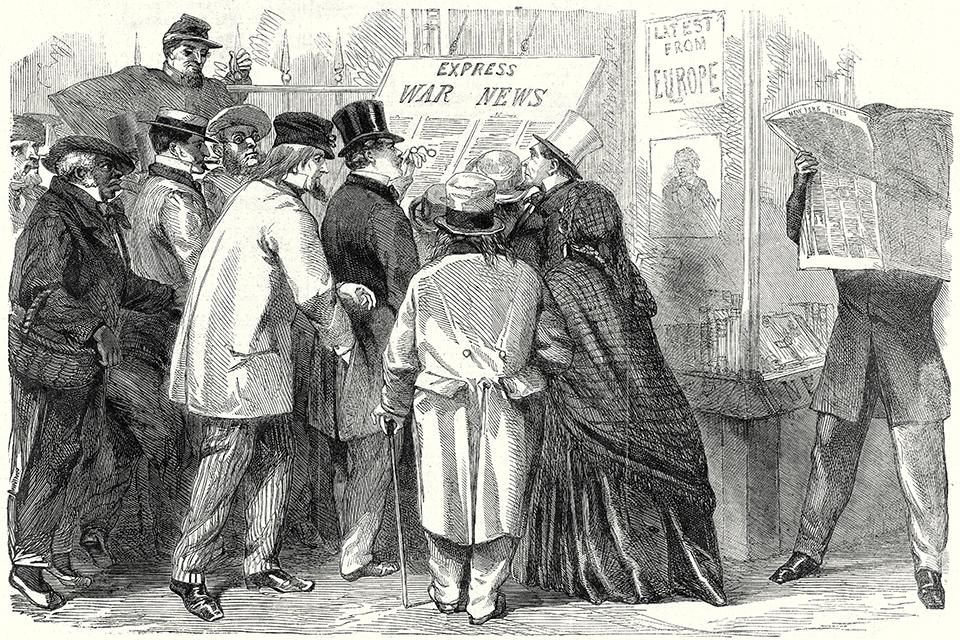

This environment encouraged pioneering American journalists to expand and innovate, from Benjamin Day’s New York Sun and the invention of the “penny press,” to James Gordon Bennett’s New York Herald, which invested vast sums in telegraph-based reporting to get news faster than its rivals.11 Christopher B. Daly, Covering America: A Narrative History of a Nation’s Journalism (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2012), 61, 104. The perception of political independence became central to the identity of these newspapers; as articulated in the first edition of the Herald, which proclaimed: “We shall support no party—be the organ of no faction or coterie.”12 The New York Herald, May 6, 1835, 1.

Despite the lofty rhetoric and commercial success, the unsatisfactory character of the American newspaper became an increasingly common complaint by the mid-19th century. For example, W.H. Russell of The Times of London – the man still regarded as the “father of war reporting” – attacked New York papers for their exaggerations, inaccuracies, and personal attacks.13 Ilana D. Miller, Reports from America: William Howard Russell and the Civil War (Gloucestershire, England: Sutton, 2001), 149-150. By the 1850s, the toxicity of the popular press was matched only by the state of the nation’s politics. On the eve of civil war, furious disagreements over slavery, in particular, were amplified further and faster across the country by increasingly antagonistic newspapers. Any notion that the press would serve as a unifying force across the nation had long since vanished.

UNCIVIL WAR

The American Civil War is notorious in the annals of media history: summarized by one scholar as “sensationalism and exaggeration, outright lies, puffery, slander, faked eye-witness accounts, and conjectures built on pure imagination…”14 J. Cutler Andrews, The North Reports the Civil War (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1955), 640. This was a perfect storm in which seemingly-insatiable demand for breaking news combined with hyper-partisan papers, the challenges of accurately reporting through the “fog of war,” and transformative (but unreliable) technology, notably the telegraph. Such a situation may seem familiar! Indeed, Civil War reporters could give today’s pink slime outlets a run for their money when it comes to misleading readers about proximity to the events that they cover. One infamous offender was Junius Browne, a reporter for the New York Tribune who produced a dramatic eyewitness account of the Battle of Pea Ridge, even though his colleagues insisted he’d never been near the battlefield. Likewise, the Battle of Shiloh in 1862 triggered a mass feat of geographical deception, as reporters based over 150 miles away produced wildly speculative accounts of heroism and villainy.15 Tucher, Not Exactly Lying, 51-52; Andrews, The North Reports the Civil War, 179.

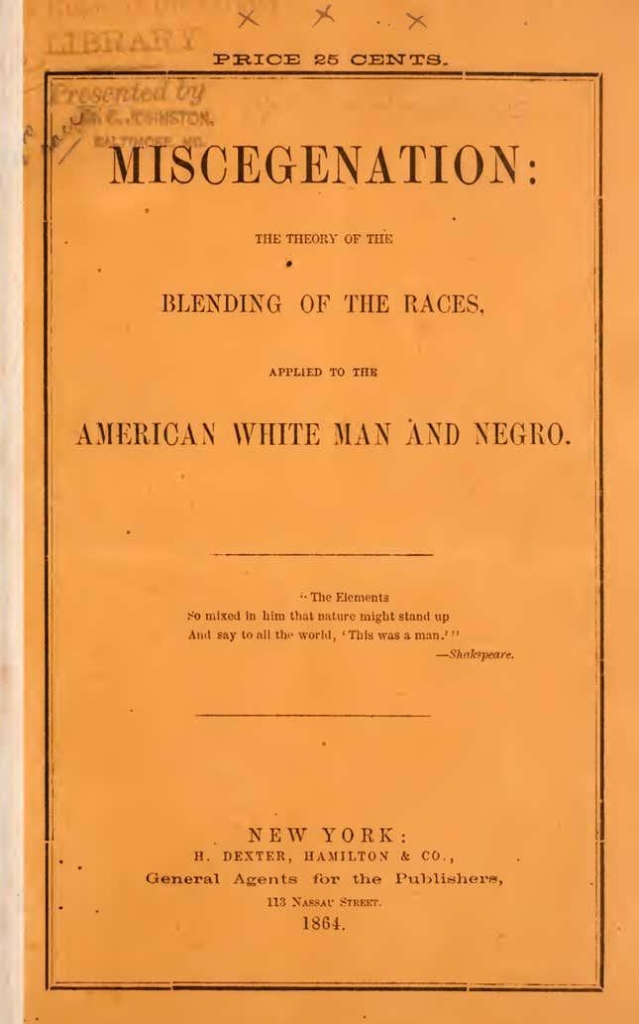

It wasn’t just the war correspondents who were up to no good. Two New York World reporters, George Wakeman and David Goodman Croly, sought to manipulate the outcome of the 1864 General Election – perhaps the most consequential in American history. The contest – which was held despite the ongoing bloody civil war – would determine the future of President Abraham Lincoln, his war policy, and his plans for emancipating America’s enslaved population. Against this incendiary backdrop, Wakeman and Croly published a pamphlet (purportedly authored by a northern abolitionist) that extolled the virtues of sexual relations between Black and white people, encouraging Lincoln and the Republican Party to formally encourage the interracial approach they termed “miscegenation.” This disinformation document – which was one of various ways in which the anti-Lincoln New York World sought to stoke public and political outrage – was intended to drive voters to the Democrats in crucial swing states, including New York. The goal was to spread fear, confusion, and mistrust: “flooding the zone with shit,” as Steve Bannon may have put it.

Anon. (George Wakeman & David Goodman Croly) Miscegenation: The Theory of the Blending of the Races, Applied to the American White Man and Negro (New York: H. Dexter, Hamilton & Co., 1864).

SPINNING SLAVERY

Such duplicitous attempts to undermine Lincoln and the Union side were not limited to the United States. Indeed, the South may well have avoided defeat had it not been for the failure of its propaganda operation in Britain – the number one target for Confederate leaders seeking diplomatic recognition and even military intervention. In order to secure this support the South needed to fix a serious PR problem: the Confederate States of America was widely (and correctly) viewed by Britons – a people with a proud sense of their abolitionist heritage – as a slave-state created by rich planter-politicians to preserve their “peculiar institution” at any cost. The Confederacy did what any nation or corporation with an image issue does today: they enlisted propagandists to launder their reputation.

Henry Hotze, a Swiss-born propagandist, was dispatched to London to persuade journalists, politicians, and the general public that supporting the South would benefit Britain. His most ambitious move was launching a fully-fledged weekly newspaper – The Index – which was surreptitiously funded by the Confederacy and edited by Hotze, who doled out generous commissions to British journalists to produce pro-Southern pieces for his paper and other British outlets. Like several of the more sophisticated pink slime operations identified by the Tow Center, The Index was carefully cultivated to appear authentic to its target audience – in this case, copying the look and feel of a British broadsheet, right down to the mimicking the editorial style and inclusion of regular features (including a literary review) that were familiar to readers.

Hotze curated the newspaper’s content to fit his purpose. For example, he rejected one article submitted by Pierre-Paul Pecquet du Bellet (a fellow Confederate propagandist) for being “violent in tone and language,” noting that “the English are an unimpressionable people and I understand them well. You set them against you the moment you show them any strong feeling.”16 Henry Hotze, Confederate Propagandist: Selected Writings on Revolution, Recognition, and Race, Lonnie A. Burnett, ed. (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2008), 31. Hotze’s efforts to shape opinion were ultimately undone when the Confederacy suffered major military defeats in 1783, convincing even the most cynical British elites that the slave-South was not the right horse to back.

BILLIONAIRES, BANKS, AND BRIBERY

Many of the loudest and best-resourced advocates for the Confederacy were commercial elites who sought to benefit most from its success – not least the business owners, merchants, and creditors who accrued great fortunes from the “empire of cotton” that was built on the brutality of the slave plantation. The propensity of wealthy elites to fund pseudo-journalism is a recurring theme in American history. Just as the Tow Center traces pink slime funding back (via an intricate and deliberately opaque web of foundations, NGOs, and corporate entities) to some of America’s wealthiest families, so there are numerous earlier examples of industrial titans exploiting the press to promote their ideological and commercial interests.

One notable episode came during the so-called “Bank War” of 1828-1832, a messy squabble over the rechartering of the Second Bank of the United States. The contest between President Andrew Jackson’s administration and the Bank, led by its president, Nicholas Biddle, saw both sides engage in widespread bribery of publishers and journalists. As Stephen W. Campbell notes in his analysis of the Bank’s PR campaign, favorable loans were issued to supportive media proprietors and secret funds used to pay reporters, while the Bank “spent somewhere between $50,000 to $100,000 in printing orders for circulating reports, treatises, editorials, and in small payments to confidential agents,” as well as lending “somewhere between $100,000 and $150,000 to editors and congressmen during the same period.”17 Stephen W. Campbell, “Funding the Bank War: Nicholas Biddle and the public relations campaign to recharter the second bank of the U.S., 1828–1832,” American Nineteenth Century History 17, no.3 (2016), 273-299. The Bank’s campaign, which was ultimately unsuccessful, specifically targeted large circulation newspapers (such as the New York Courier and Enquirer, the United States Telegraph, and the National Intelligencer) in order to maximize its reach and – in theory – its influence.

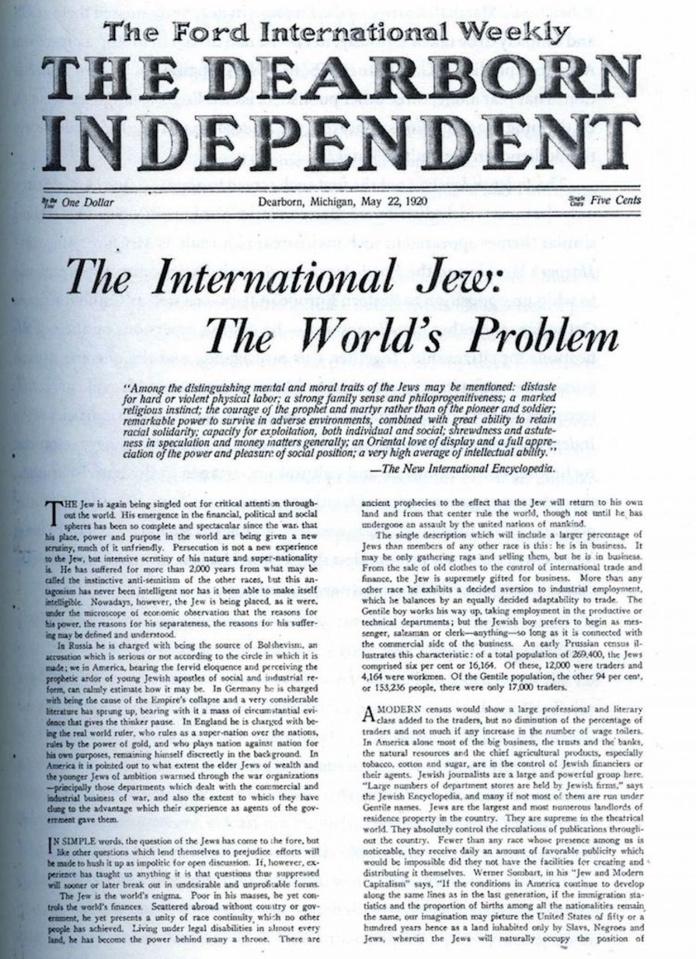

Another option for uber wealthy Americans has been to launch their own publications or purchase an existing title, which can then be refashioned into a personal propaganda organ. One example of the latter approach came in 1918, when automobile magnate Henry Ford purchased the Dearborn Independent, a small, inconsequential weekly newspaper based outside Detroit. Ford transformed the publication into a mass-circulation paper – distributed via Ford dealerships (which were required to sell subscriptions), as well as thousands of free copies sent “unbidden” to schools and libraries across the country.18 See Victoria Saker Woeste, “Insecure Equality: Louis Marshall, Henry Ford, and the Problem of Defamatory Antisemitism, 1920–1929,” Journal of American History 91, no.3 (Dec. 2004), 877–905.

The publication was not designed to make a profit (it no longer accepted advertising), but rather to provide Ford with a platform to project his views to the American public. The nature of these views became clear in 1920, when the Dearborn Independent published a series of “investigations” that claimed to reveal how the “International Jew” secretly controlled global affairs. The newspaper even syndicated The Protocols of the Elders of Zion, amplifying this notorious work of antisemitic disinformation (originally created by the Russian secret service to promote pogroms) to the American public and legitimizing falsehoods that endure a century later.

PROPAGANDA FOR PEACE

Henry Ford’s use of the Dearborn Independent demonstrates how the newspaper model can be exploited to promote particularly nefarious causes. And yet, one final, largely-forgotten episode from American history serves as a timely reminder that not all media manipulations have been motivated by harmful intentions.

In 1841, President John Tyler (the “Accidental President”) was trying to prevent the United States becoming embroiled in another costly war with Britain – this time over a long-running dispute about the boundary of northern Maine and British Canada.19 See Frederick Merk, Fruits of Propaganda in the Tyler Administration (Cambridge, M.A.: Harvard University Press, 1971). Neither side wanted conflict, but political and public opinion in Maine – stirred up by hawkish local newspapers – was strongly in favor of defending the state’s territory by any means necessary. Such belligerence posed an obstinate barrier to an Anglo-American peace agreement – particularly as Maine’s rabble-rousers had effectively framed the dispute as a test of American resolve.

The solution was to launch the first government-financed (via a secret presidential contingency fund) “systematic propaganda campaign to manipulate public opinion” in American history.20 Edward P. Crapol, John Tyler, the Accidental President (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2012), 122-123. The press was central to this scheme, which was masterminded by Francis O.J. Smith, a Maine congressman turned lobbyist-propagandist. Smith’s plan was to “prepare public sentiment in Maine for a compromise of the matter” by bribing local politicians, journalists, clergy, and other opinion-formers in the state – creating the false impression that the push for peace “be made to seem to have its origin with [the people of Maine] themselves.”21 Francis O.J. Smith to Daniel Webster, June 7, 1841, quoted in Merk, Fruits of Propaganda, 143-145. The operation proved highly effective, not least because Smith’s funds enabled him to “adjust the tone and direction of the [Maine] party presses, and through them… public sentiment” – all without disclosing that the U.S. government (and, even more shockingly, the British) were bankrolling his work. The eventual outcome was the 1842 Anglo-American treaty that laid the foundations for the (broadly) stable “special relationship” that has endured ever since.

“GOOD INFORMATION” VS “BAD INFORMATION”

This whole episode raises a difficult question: did the end justify the means? Secretary of State Daniel Webster (another legendary American statesman with a grand statue in New York City) praised the Maine scheme as a “movement of great delicacy.” And yet, the idea that the public should be deceived for their own good is troubling – a recipe for exploitation that has been used to justify genocides, enslavement, illegal invasions, and more. The fact that media coercion and corruption has so often facilitated these crimes provides extra pause for thought – especially when considering the myriad of ways in which people are being targeted by propaganda and disinformation today.

There are certain parallels between Webster’s pragmatism and justifications offered by advocates of using partisan local news to promote political messaging – especially those on the political left. One of the most visible networks is Courier Newsroom, a self-described “pro-democracy…civic news organization” that is led by former Democrat strategist Tara McGowan and was funded via a progressive “dark money network.” Courier operates news outlets in ten key swing states (with Texas “coming soon”), producing content that is microtargeted at voters (via extensive social media amplification) with the intention to inform, but also to persuade.

Of course, advocacy journalism also has a rich heritage in America – largely associated with marginalized groups (in particular, Black Americans) who used their own publications to counter the prejudice, lies, and neglect of the so-called “mainstream media.” McGowan defends Courier’s approach (and differentiates its work from conservative equivalents) by claiming that its websites spread “good information” needed to neutralize “bad information,” in this case propagated by the right.

Courier News homepage, Jan. 22, 2024.A similar rationale is offered by another progressive “pseudo-news” organization, the American Independent, which is also funded (via a complex web of Democratic-aligned PACs and big-money donors) to manage“22Lachlan Markay & Thomas Wheatley, “Democrats’ Swing-State Local News Ploy,” Axios, Oct. 6, 2022, https://www.axios.com/2022/10/06/democrats-local-news-david-brock. at least 51 locally branded news sites” in electorally-signification locations. Jessica McCreight, executive editor of The American Independent, defended her organization’s blurring of information, advocacy, and campaigning, telling Axios that it works to combat “dis- and misinformation” that is spreading across the U.S., especially “where local news outlets shut down.” This justification is reminiscent of one used by the state-funded Anti-Jacobin in 1797, which promised to provide Britons with “a contradiction and confutation of the falsehoods and misrepresentations… found in the Papers devoted to the Cause of sedition and irreligion.”23 Quoted in Stuart Andrews, The British Periodical Press and the French Revolution, 1789-99 (New York: Palgrave, 2000), 74.

THE NEW NEWS?

While progressive organizations like Courier News have taken steps to be more transparent about their intentions and funding than conservative peers, their effectiveness is still largely premised on misleading audiences into thinking they are consuming something that they are not. The Tow Center report quotes Matthew Pressman,24Pink Slime”: Partisan journalism and the future of local news,” Tow Center for Digital Journalism, Jan. 2024, 131. a Professor of Journalism at Seton Hall University, who describes the mixing of advocacy journalism with political campaigning as “dicey” – not least because the average reader is unlikely to differentiate between local news content published by politically-affiliated organizations and that produced by independent news outlets adhering to contemporary norms.

Until the late 19th century (at the earliest) most Americans would not have thought anything usual about a news organization seeking to fulfill a political role – nor even expect that everything they read in a newspaper was supposed to be true.25 Tucher, Not Exactly Lying, 7 And yet, pink slime journalism now feels so deceptive because “objectivity” became the central pillar of American journalism from the 1920s onwards – a differentiator between the propagandist and the journalist.26 Schudson, Why Journalism Still Matters, 51. Formal codes of conduct for journalists were introduced and drilled into new reporters via professional schools and workplace traineeships – cementing the idea that journalism was a respectable profession with sacred principles. One such principle of “Ethical Journalism” is that financial inducement must never influence editorial output.

However, in recent years there has been growing uncertainty about the traditional ways that journalism is done – notably the valorization of “objectivity.” More journalists, scholars, and educators now debate whether long-standing conventions preserve inequalities and mislead audiences, challenging the orthodox view that “the focus of those engaged in journalism is to uncover and inform… not to persuade or manipulate the public to embrace a particular policy solution or outcome.”27 It is notable that the authors (two journalists) of this book – which seeks to shape the values and practices of reporters, and remains a staple of “J-school” education – felt the need to add this sentence into their updated edition, published in 2021. Bill Kovach & Tom Rosenstiel, The Elements of Journalism: Revised and Updated, 4th ed. (New York: The Crown Publishing Group, 2021), 195. By contrast, the Courier Newsroom website not only touts the organization’s expertise at persuading voters and influencing elections, but spotlights the endorsement of a reporter who declares that “objectivity is a myth.”

Such ideological reckonings are typically triggered by high-profile controversies in which the press is deemed to have failed – whether it be insufficiently scrutinizing warmongering politicians or inadequately covering racially-motivated violence. The sense of growing uncertainty about established norms and polarization within newsrooms today can be seen in the numerous internal squabbles spilling out into the public domain. These battles compound already daunting financial challenges facing every American news outlet. The much-debated“ crisis” of local journalism is clearly contributing to the resurgence of politically-funded, politically-motivated journalism.

According to research by Northwestern Medill, 2.5 newspapers per week close down in America. The resulting “news deserts” make attractive targets for pink slime colonizers, especially when these happen to be strategically-significant locations too. For example, Chevron is not only publishing pseudo-news in the Texas Permian Basin because this oil-rich region is operationally important, but also because their content is likely to be more impactful now that many local news outlets have closed down.

LESSONS FROM HISTORY

Now, in something of an ironic twist, it seems that one option for saving local news – and halting the surge of pink slime – is for politicians to intervene. President Biden’s “Build Back Better” plan proposed distributing $1.67 billion over five years to newspapers, websites, and broadcast stations that cover local stories. The proposed tax credits would “mark the first time the federal government has offered targeted support in response to the decline of local news” – a remarkable proposal reminiscent of policies introduced to boost the fledgling newspaper industry back in the 18th century. And yet, this approach raises legitimate concerns about political-press entwinement and long-term financial dependency. Is more political involvement in local news really the best way to mitigate hyper-partisan content? Who decides which outlets produce journalism and which churn out slime?

An alternative approach is to increase corporate ownership and funding of local news. Ten years ago, occasional “World’s Richest Man” Jeff Bezos purchased the Washington Post (perhaps the world’s most famous “local” publication) for $250 million, while the Google News Initiative and Meta (formerly Facebook) Journalism Project have directed large sums towards local news outlets – albeit fleetingly. However, is funding journalism through the profits of corporate America a preferable alternative to government subsidies? As history shows, there is good reason to be suspicious about billionaires who want to own media (or social media) platforms – especially when the prospect of generating profitable returns has never seemed slimmer.

For now, the gloomy financial outlook is encouraging bad faith actors to pollute the local news ecosystem with low-cost, low-quality content masquerading as journalism – a far cry from the locally-staffed, locally-funded, trusted newspapers of yore. Nevertheless, we must not mistake the central cause of the local news crisis (the internet and social media) as the catalyst for this media manipulation. Instead, the rise of digitally-driven pink slime – much of it unsubtle, unsophisticated, and ineffective – is exposing uncomfortable truths about American journalism that go back to the very start.

Stuart Anderson-Davis is a Ph.D. candidate in the Communications program at Columbia University’s School of Journalism. His research focus is the history of disinformation.

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.