Sign up for The Media Today, CJR’s daily newsletter.

“Official voter guide,” read the mailers sent to voters in seven battleground states ahead of the 2022 midterms.

Presenting simple side-by-side comparisons of down-ballot candidates’ views on key issues like abortion, education, and democracy, the author assured readers they’d “had researchers dig through local candidates’ backgrounds, statements, and votes on key legislative issues, then provide that information to voters like you—so you can make an informed choice on Election Day.”

Given they were produced by My Voter Information, a project of Forward Majority Action, a dark-money group formed in 2017 to elect Democrats to state legislatures, it comes as little surprise these mailers had a strong political slant.

Nor is it any shock that, for six of the seven states, most of the material researchers “dug through” to construct these caricatured candidate profiles was low-hanging fruit like candidates’ campaign websites and social media posts, the websites of relevant advocacy groups, and online stories from local TV stations or newspapers.

The exception was the mailers covering races in Michigan.

Analysis of 92 mailers shared on the Michigan page of Forward Majority Action’s website found 69 citations of the Main Street Sentinel, a mysterious, short-lived quasi–local news site that targeted Michiganders on Facebook, garnering over 100 million impressions in ten months thanks to an untraced ad spend of over $1.4 million.

The Main Street Sentinel

The Main Street Sentinel comprised three digital entities—a website, a Facebook page, and an Instagram account, all of which were created in February 2022.

The Facebook page, on which it self-categorizes as a “Broadcasting & Media Production Company,” was created on February 7, 2022, and the first post was made on February 24, 2022. Its Instagram page shows only that the account was created in February 2022, and the earliest post visible as of August 14, 2024, is dated March 1, 2022.

The website’s domain was registered on February 17, 2022, according to ICANN Whois records. The Wayback Machine’s last capture of an operational website is dated February 8, 2023. It now redirects to a template page from Teal Media’s Archie, a platform that promises websites “on a quick timeline and a limited budget” for “big nonprofits with small initiatives, new organizations just getting started, and political campaigns that need donations yesterday.” Teal counts Courier Newsroom, the partisan local network that originated from liberal dark-money group Acronym, among its clients.

The Wayback Machine’s last capture of the Main Street Sentinel homepage, dated February 8, 2023.

The Main Street Sentinel was clearly conceived to exploit Facebook’s targeting capabilities. According to Meta Ad Library data, between $1,215,000 and $1,665,689 was spent on ads for the page between February 25, 2022, and November 18, 2022. (The Meta Ad Library gives a figure of $1,412,891, which it describes as “the estimated total amount of money this advertiser has spent on ads about social issues, elections, or politics.”)

This outlay appears to have gotten the Sentinel in front of a lot of Michiganders. Meta’s Ad Library provides minimum and maximum figures for ad impressions—the “number of times an ad was on a screen, which may include multiple views by the same people”—and the approximate location of the Facebook users who were served the ads. Per this data, Main Street Sentinel ads received between 108.5 million and 123.9 million impressions, 99.4 percent of which were in Michigan (approximately 107.9 million). As a further measure of the extent to which Michigan was targeted, California ranked second, with around 61,000 impressions.

The Sentinel’s first ad campaign began on February 25, 2022, with 30 ads for ten stories. These can be grouped into four thematic groups:

- Four boosted Michigan governor Gretchen Whitmer, highlighting her policy priorities, bipartisan praise for job creation, and external approval of her education policy proposals (e.g., “Experts: Gov. Whitmer’s Education Budget Prioritizes Classrooms, Books, School Quality”).

- Two attacked Michigan’s GOP senators and GOP candidates for attorney general (e.g., “GOP-Led Michigan Senate Passes $2 Billion Tax Cut for Big Corporations”).

- Three painted a picture of a booming US economy, directing credit toward the early phase of the Biden administration (e.g., “‘Supercharged’ U.S. Economy Gained 6.6 Million Jobs in Biden’s First Year”).

- One framed a six-day blockade of the Ambassador Bridge between Detroit and Ontario by a “freedom convoy” protesting cross-border vaccine requirements as “the Canadian trucker protest.” Having drawn support from Donald Trump, Fox News personalities, and “right-wing extremists and armed citizens in Canada,” the protests had become a divisive partisan issue in Michigan’s gubernatorial race, with GOP candidates blaming Whitmer and the Biden administration for “demonizing the truckers,” lacking leadership, and pushing “big government socialism” by strangling personal freedom (“Canadian Trucker Protest Cost Michigan Workers at Least $51 Million in Wages”).

These ads, which cost $8,900, received 1,078,000 impressions, according to Meta data. All 27 of the ads for which the Meta Ad Library returns regional data were seen exclusively by users in Michigan. (The Meta Ad Library does not return location data for ads with fewer than 1,000 impressions.) Therefore, Facebook delivered over 1 million impressions to this faux news operation within four days of its first post.

Murky provenance

The Main Street Sentinel received a smattering of attention at the beginning and end of its short life, much of which noted the opaqueness around its ownership.

On March 27, 2022, Axios mentioned it as part of a report on Real Voices Media, a group responsible for “a massive network of social media communities in political battleground states that can activate ahead of elections and policy fights.” Of the Main Street Sentinel, Axios wrote, “It’s not clear who’s behind the site. Its listed publisher, Star Spangled Media LLC, was formed last month [February 2022] in New York and lists a registered agent service as its only officer.”

Shortly afterward, on April 11, 2022, conservative news site National Review covered the Sentinel under the headline “Your Favorite Facebook Page May Be a Trojan Horse for Progressive Propaganda.” The report characterized the Sentinel as “a website with a name that screams small-town news, but that is actually a left-wing propaganda site that serves up a heavy dose of Democratic spin and White House talking points.”

A month before Election Day, the Sentinel was cited in analysis copublished by Substack newsletters Statehouse Action and FWIW, the latter of which has longstanding ties to Courier Newsroom. FWIW is run by Kyle Tharp, who held various communications positions at Acronym and Good Information Inc., and is now national managing director of Courier Newsroom. FWIW is now listed as a Courier Newsroom newsletter.

Presenting a relatively positive take on the Sentinel, the FWIW/Statehouse Action authors opined, “Out of all the states that have competitive legislative elections this year, Democrats and their allies seem to be running their most sophisticated digital operation in Michigan.”

They added:

Candidates, the state party, and outside groups all are hammering Republicans across the state with abortion-related advertising.

Over the past 90 days, the top spender on political Facebook ads in Michigan was not Gov. Gretchen Whitmer’s campaign or some large national advocacy group.

Rather, it was a relatively obscure progressive digital political outfit called the Main Street Sentinel. The liberal site, somehow affiliated with a progressive Facebook network called Real Voices Media, has spent over $700,000 on ads supporting Democrats running for the state legislature and other offices.

Continuing its rundown of the biggest digital ad spends around Michigan’s down-ballot races, it was noted that Forward Majority Action Michigan had “launched new Facebook ad campaigns attacking Republican down-ballot candidates.” Three of the ads launched by Forward Majority Action Michigan in September and October went to myvoterinformation.org.

Shortly afterward, a couple of weeks before Election Day, NewsGuard featured the Sentinel alongside Courier Newsroom, the American Independent, and Metric Media in a report detailing almost $4 million of political ad spend on Meta platforms. They too noted the obscure provenance, reporting, “The Main Street Sentinel states on its website that it is owned by Star Spangled Media LLC, [but] the group’s Facebook and Instagram ads say that they are ‘Paid for by The Main Street Sentinel’—a name that does not appear on any state business registries, and that give the ads a patina of journalistic authenticity.” NewsGuard’s finding received further coverage from Bloomberg‘s Davey Alba under the headline “Meta is making millions off political ads from fake ‘pink slime’ newsrooms.” Alba noted a connection to Democratic strategist Will Robinson, first reported in the March report from Axios, but added, “Other investors aren’t known, but the site has run multiple stories with President Joe Biden and Michigan Governor Gretchen Whitmer as beneficiaries.”

To date, nothing has been reported about the Main Street Sentinel’s function outside of Meta platforms.

Forward Majority Action

Forward Majority is a super-PAC formed in 2017 to help Democratic candidates in state legislative races. It is affiliated with Forward Majority Action PAC and has numerous state-specific spin-offs. Forward Majority Action Michigan was the biggest recipient of funds from Forward Majority Action PAC in the 2022 election cycle, according to Open Secrets.

At the super-PAC’s 2017 launch, Politico wrote, “Forward Majority’s model includes targeting more races than most local parties or state caucuses are likely to touch. The goal is to flip chambers from GOP hands to Democratic control by using the kinds of expensive campaign tactics seldom used in such local races, including polling and message testing.”

According to OpenSecrets, Forward Majority received $4.1 million from the Sixteen Thirty Fund, the dark-money group with a track record of funding deceptive media operations like the Main Street Sentinel. As Anna Massoglia reported:

Sixteen Thirty Fund sponsored social media pages and digital operations for five pseudo local news outlets in three states in 2018. They appeared to be independent of each other, but promoted themselves with nearly identical digital ads.

Facebook pages operating under the auspices of the Colorado Chronicle, Daily CO, Nevada News Now, Silver State Sentinel and Verified Virginia gave the impression of multiple free-standing local news outlets with unique names and disclaimers. But the sponsors of those ads are merely fictitious names used by the Sixteen Thirty Fund, according to digital ad data and incorporation records from the D.C. government.

As of the 2022 midterms, the Target States page on ForwardMajority.org stated, “Forward Majority Action is excited to be supporting Democratic candidates across several key targeted states.”

Pages for eight target states, accessible via the Wayback Machine, each showed a breakdown of “information about that state’s program.” This included Forward Majority’s target districts, a breakdown of which subset of the electorate would be targeted, the digital ads with which they would be targeted (usually via YouTube), and the accompanying strategy for physical mail.

The mail strategy for Michigan—dated October 27, 2022, eleven days before Election Day—states, “We will be mailing voters with a midterm turnout score >5, middle partisans roughly ranged 30-60.”

Alongside the five dates on which different mail pieces would be “dropping” (which ranged from October 5 to 28), Forward Action linked to PDFs of the mailers it would be sending to voters who met its target criteria.

A total of 92 mail pieces were shown for Michigan, the most for any of the eight target states.

The file names all followed the same pattern:

[State]-[Mail Piece Number]-[Chamber and District].pdf

e.g., MI-M01-HD22.pdf (Michigan-Mail Piece 1-House District 22)

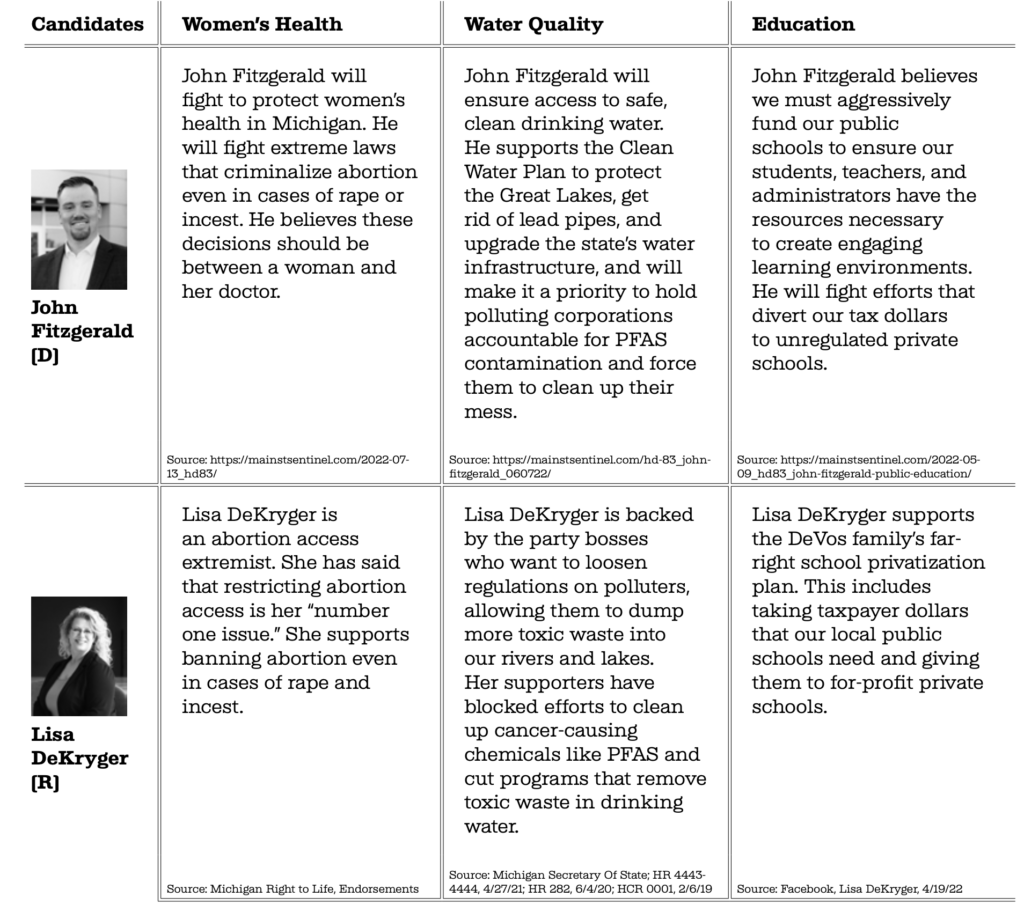

Each mail piece followed the same basic formula of contrasting the Republican and Democrat candidates’ stances on three key issues (e.g., women’s health/abortion access, water quality, education/public schools, environment, public safety, and taxes). Citations were provided for each.

To give one example, information about the Michigan Senate District 9 candidates’ views on women’s health stated that the Democrat, Padma Kuppa, “opposes efforts to ban abortion and will enshrine the protections of Roe v. Wade into state law,” while her Republican rival, Michael Webber, “is supported by a far-right anti-abortion group and opposes access for women even if they are victims of rape or incest. He even voted to restrict access to birth control.”

The curious intersection of the Main Street Sentinel and Forward Majority Action

The 69 citations of the Main Street Sentinel—all of which related to Democratic candidates—were spread across 38 Forward Action mailers. Of these, 57 were found in 26 mailers covering House races in six districts. The other 12 appeared in 12 mailers covering three districts’ Senate races.

This, of course, means the profiles of some candidates cited the Main Street Sentinel multiple times. At the most extreme end of the scale, all five mailers covering the House District 83 race between John Fitzgerald (D) and Lisa DeKryger (R) relied on the Main Street Sentinel to support all three claims about Fitzgerald’s policy positions.

A Forward Majority mail piece comparing the views of John Fitzgerald (D) and Lisa DeKryger (R), candidates for Michigan House District 83 in the 2022 midterms, on women’s health, water quality, and education.

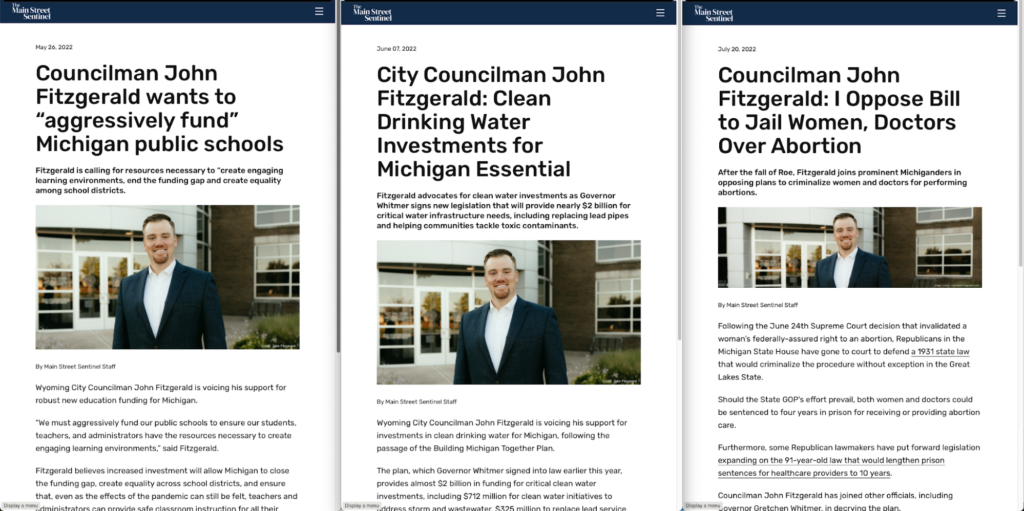

Three Main Street Sentinel stories cited in a Forward Majority mailer to illustrate John Fitzgerald’s stance on education, water quality, and women’s health.

Another curious coincidence is that the URL slugs for the Sentinel stories followed the same “[Chamber and District]” naming convention used for the PDFs of Forward Majority’s mailers. For example, where Forward Majority’s mailers promoting Fitzgerald were MI-M01-HD83.pdf, MI-M02-HD83.pdf, etc., the URLs of the articles cited as evidence of his views on key issues were:

- mainstsentinel.com/2022-07-13_hd83/

- mainstsentinel.com/hd-83_john-fitzgerald_060722/

- mainstsentinel.com/2022-05-09_hd83_john-fitzgerald-public-education/

We don’t know that Forward Majority Action has any connection to the Main Street Sentinel. The group didn’t respond to requests for comment.

What we do know is that they were extremely willing to leverage it as part of a targeted influence operation. That this supposed news site was repeatedly cited in physical mailers to augment and reinforce narratives circulated through an expensive digital ad campaign shows another simple utility of this electioneering tactic.

We also know that the Main Street Sentinel is remarkably consistent with a strategy of leveraging digital platforms for localized information warfare that Forward Majority set out in a “Blueprint for Power” published in January 2022.

Making the case that Democrats’ outmoded digital playbook had given Republicans carte blanche to influence persuadable audiences by targeting them with localized political narratives, this document had many echoes of the infamous memo Tara McGowan sent to Acronym stakeholders outlining her vision for what would become Courier Newsroom.

The second of “Three Accelerants to Build Power” outlined in the Forward Majority document—titled “Long-Term Narrative and Brand Development with Key Audiences”—prescribed the perceived problem for Democrats:

An Out-of-Date Playbook Can’t Compete with Right-Wing Propaganda: … [T]he vast majority of ordinary voters spend only moments making their vote choice, a decision dominated by existing narratives about the parties, increasingly influenced by right-wing media, disinformation and propaganda.

This was followed by a vision of a solution, which primarily amounted to a strategy of fighting fire with fire:

Opportunity to Cut Through by Building Local Narrative and Brand: To counter this, particularly in Republican trifecta states, Democrats need a local communications operation that is similarly relentless, but more astute and opportunistic. Going forward, as we continue to move new voters into the electorate—and long before campaign season starts—we must help to reshape local political narratives in our targeted districts. This includes accountability communication that shines a light on the track record of incumbent Republicans on unpopular legislation, builds the local Democratic brand, dents the GOP brand, and highlights how state legislatures impact people’s lives. Democrats have been over-built on targeting, and under-built on content. This means we know who to communicate with, but far less on how to most effectively communicate to move sentiment and achieve electoral goals. What’s needed is cutting-edge approaches to content sourcing, testing, and dissemination, leveraging earned and paid media. Notably, this local brand cultivation and strategic communication has the potential to influence not only local races, but to seed from the ground-up winning narratives and shifting party affinity that can influence the broader electorate.

The Main Street Sentinel arguably had the air of a disposable Courier-lite. It focused on a competitive swing state; it had a strategy for identifying persuadable voters and spent large sums micro-targeting them via Facebook ads; it emphasized the importance of targeting voters with a small number of localized political narratives.

Speaking in the immediate aftermath of Joe Biden’s 2020 election victory, McGowan framed partisan local news as peerless in its ability to help Courier achieve its overtly political goals. Notably, McGowan implied that Courier’s expensively assembled network could be something of a short-term political endeavor:

I certainly wouldn’t have invested in a local news network if there were models that I was seeing start to gain traction and success at covering that territory and countering disinformation at the local level. I’m just not somebody who’s willing to twiddle my thumbs and watch democracy die in the meantime if there are short-term solutions that can be deployed at scale.

In the same interview, McGowan described the expensive but effective pursuit of “marketing…news content to audiences who live in these narrative deserts” and “deliver[ing] it on the news feeds and platforms where they spend their time.”

While the seven-figure ad spend puts it at the pricier end of the spectrum, it could be argued that the Main Street Sentinel is a manifestation of McGowan’s reasoning taken to its logical conclusion.

Active for less than 12 months, it was a short-term solution. Having generated at least 108 million impressions, it was deployed at scale. By using Facebook’s targeting capabilities to reach a pre-identified segment of persuadable voters in a specific location, it was marketing narratives to micro-targeted audiences on the platforms where they spend their time. And while its total outlay of around $1.4 million was closer to the sum Acronym was allegedly spending each week in the run-up to the 2020 election, it is still, to use McGowan’s phrase from the same interview, “insanely expensive.”

Thanks to platform companies, this problem isn’t going anywhere

The case of the Main Street Sentinel shows how easy platforms make it for deep-pocketed political influence operations to pollute geo-specific news feeds at scale. In this case, a brand-new page was able to accrue over a million impressions in one targeted state within four days of its first post. By the time it was disbanded, having served its political purpose, it had accrued at least 108 million impressions in under 12 months.

Such figures only reinforce why this trend shows no sign of abating.

Earlier this year, research by Clemson University’s Media Forensics Hub showed that groups with ties to Russia have used generative AI to launder pro-Kremlin narratives on fake local news sites with names like DC Weekly, the Miami Chronicle, and New York News Daily.

The emergence of these sites suggests that the appetite for polluting the digital news ecosystem with political narratives disguised as local news remains strong.

The case of the Main Street Sentinel doesn’t just highlight the ongoing appeal of this playbook, or the flagrant hypocrisy of groups that claim to be driven by a commitment to strengthening democracy while undermining journalism and debasing the information ecosystem. It also highlights platform companies’ lack of interest in doing anything about it.

The disparity between the ease with which political actors can flood the information ecosystem and the ease with which the citizens that are being bombarded with it (and researchers interested in examining it) can establish provenance could not be greater. That, of course, comes down to money.

While we may have a sense of how many times the Sentinel successfully infiltrated Michiganders’ Facebook feeds, we can’t determine whether it succeeded in persuading voters.

But we can be sure that if its operators deemed it a success, they will have something similar in the works ahead of November 5. As will countless contemporaries from across the political spectrum.

Whether their platform of choice is Facebook, TikTok, Instagram—or, indeed, paper—we’ll be on the lookout.

The Tow Center maintains a list of politically backed and partisan news sites here. It includes details of individual networks, copies of physical mailers that have been sent, and existing research about individual networks. If you receive a physical mailer, have examples of similar networks operating in your area, or would like access to more granular data, please get in touch with us here.

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.