Sign up for The Media Today, CJR’s daily newsletter.

Will I go to prison for violating the terms of service? This is the question journalists must ask themselves, now, when writing data stories based on public information collected from a website, such as Facebook or Twitter.

Violating a terms of service that prohibits scraping can carry with it possible criminal liability under the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act—the act under which activist Aaron Swartz, who killed himself during the course of his prosecution, was charged as a felon. That law includes a provision that prohibits exceeding “authorized access” on a website, such as breaking its terms of service, that triggers caustic penalties including possible prison time.

No journalists have been prosecuted under this statute, but their sources have, and some journalists have been asked to stop using specific reporting tools by Facebook. Moreover, the company is well within its legal rights to bring claims against journalists in the future under the statute. To address these issues, last month, the Knight Institute wrote a letter to Facebook, asking the company to change its terms to create a news-gathering exception to its ban on scraping. So far, the company has not complied with this request.

The letter, citing my newly published report by the Tow Center for Digital Journalism, lists a variety of journalists who have continued to pursue stories on Silicon Valley despite possible penalty under the CFAA. For instance, the Knight letter cites a Gizmodo report that explored Facebook’s algorithms identifying “people you know” and a New York Times article that exposed fake accounts. The letter also names a PBS Newshour reporter whose story about political advertisements was completely stymied for fear of penalty.

Facebook was asked to respond to the Knight letter by last Friday. To date there has been minimal public response by the company. A statement by Campbell Brown, the head of the company’s global news partnerships, reads: “We do have strict limits in place on how third parties can use people’s information, and we recognize that these sometimes get in the way of this work.” The company has not, however, amended or removed those limits. (Editor’s note: The Knight Institute informed the author, after posting, that Facebook reached out to them in response to the letter. The Institute and Facebook are in continuing discussions about the “safe harbor” proposal.)

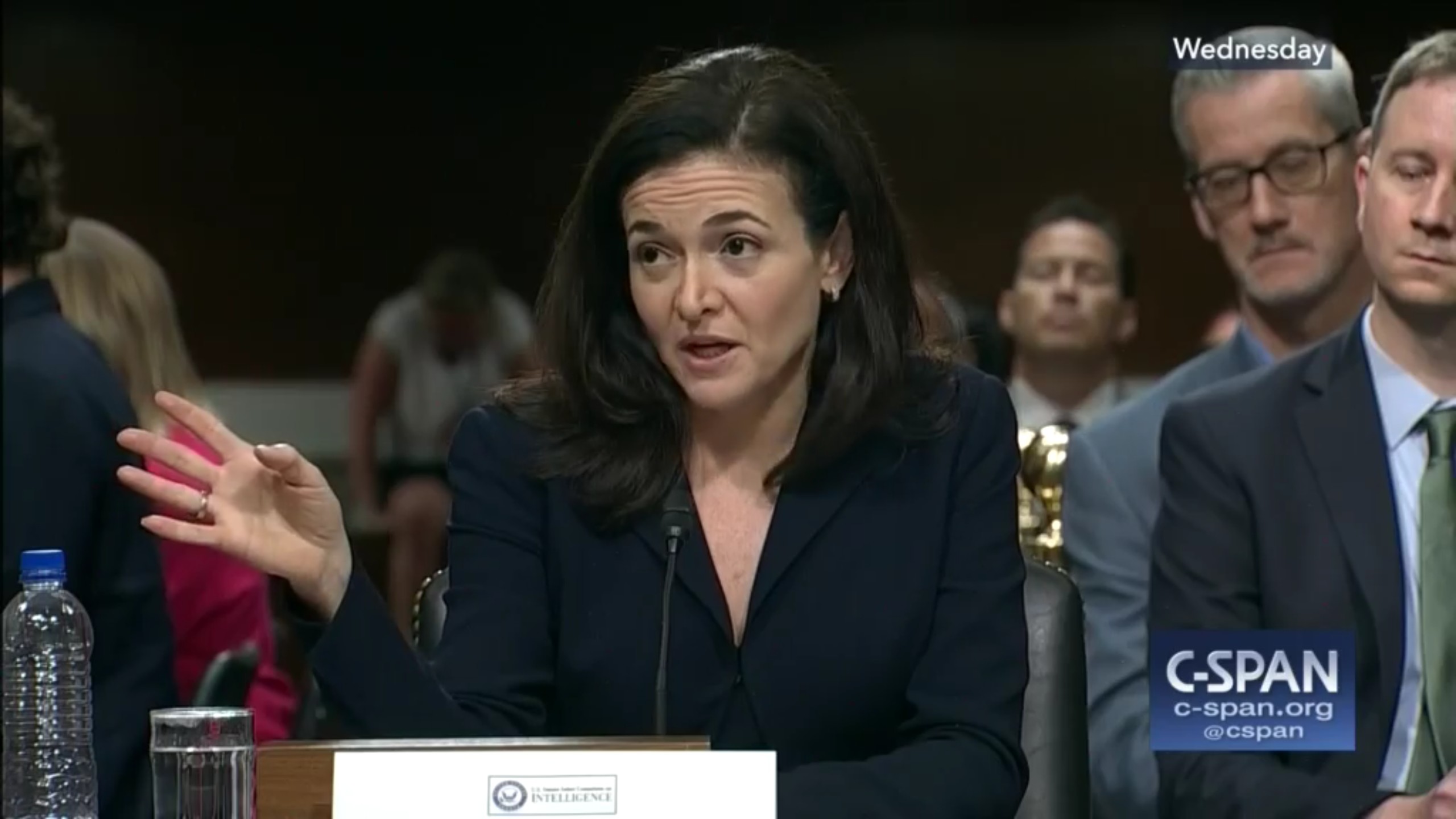

Nor have Facebook’s executives given journalists much comfort when they appeared, alongside Twitter’s CEO, before the Senate Intelligence Committee, which is considering how and whether to regulate the companies, as lawmakers are increasingly concerned about the lack of transparency around issues of public interest from technology industry.

READ: The science of fact-checking

Still, Silicon Valley seems to recognize a problem is amidst. As Jack Dorsey wrote in his testimony, transparency is key: “We know the way earn more trust around how we make decisions on our platform is to be as transparent as possible.”

At the same time, promoting transparency, news stories that compile data points for large-scale analysis are more popular than ever, as scraping has become a common tool. As Paul Bradshaw, who runs the MA in Data Journalism at Birmingham City University, puts it, scraping is “one of the most powerful techniques for data-savvy journalists who want to get to the story first, or find exclusives that no one else has spotted.”

Scraping is, simply, the act of programming a computer to collect information from an online source. The information gathered might be publicly viewable or not. It may be spreadsheets or documents which would otherwise take countless hours to sieve through. In other cases, it might be a company’s source code or software.

The popularity of this technique coincides with the increasing demand for journalists to investigate companies that have amassed control over critical swaths of data that contain the most intimate details of our lives, and yet, remain largely unregulated in the United States.

For instance, the team at ProPublica was able to report on Facebook using the publication’s Political Ad Collector extension for Google’s Chrome browser, which is able to calculate the statistical likelihood that an ad contains political content. The application yielded interesting results, such revealing Uber targeted specific demographics with their ads.

Facebook even thanked Julia Angwin, then a senior reporter at ProPublica, for her reporting: “Thanks @JuliaAngwin. You’ve done a lot to uncover issues in our ads systems, which we’ve worked hard to fix.”

ICYMI: How YouTube radicalizes its viewers

Angwin’s reporting did not scrape Facebook’s programming interface—it might have triggered the CFAA, if it had—but other valuable reporting has scraped data to great effect: The Atlanta Journal-Constitution developed about fifty scrapers for a national investigation called Doctors & Sex Abuse. The resulting investigation, a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize for national reporting in 2017, found hundreds of physicians accused of sexual misconduct were still practicing with a license. The scrapers were tailored to agencies across the country and were used to collect more than 100,000 disciplinary documents.

Similarly, a recent academic study on Facebook and Twitter shows that examining data from Silicon Valley companies can yield profound conclusions. There Researchers from Stanford, New York University, and Microsoft examined data on Facebook and Twitter to determine that suspected hoax and propaganda sites have been getting increasing engagement on Twitter since the 2016 election.

Because reporters must often either use these companies’ proprietary programming interfaces in order to gather the necessary information, or act covertly, legal advice has become essential in news gathering for these types of stories. Newsrooms with larger resources have attorneys who can advise journalists around the CFAA. Indeed, several newsrooms have begun providing legal trainings on the terms of service and the CFAA. But newsrooms without counsel as well as freelancers, who operate without legal advisors, are left largely at risk—leaving legislators at bat.

And many news investigations have been stymied by the specter of the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act’s penalties: As a newsroom attorney at The Center for Investigative Reporting, which has one of the few data teams in the country, I can report that this issue comes up regularly. While we have found ways of obtaining needed data through legal paths, the law creates real hurdles—and those hurdles must be removed.

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.