Sign up for The Media Today, CJR’s daily newsletter.

News archiving has not just changed, it has become endangered. In our new report for the Tow Center for Digital Journalism, A Public Record at Risk: The Dire State of News Archiving in the Digital Age, we examine the current practices—or lack thereof—related to content preservation among news organizations. The industry, we argue, needs to reassess its priorities and address significant shortfalls in resources and planning if future generations are to have a set of tools vital to combating propaganda and holding the powerful to account for actions not documented by governments or in corporate records.

Between March 2018 and January 2019, we conducted interviews with 48 individuals from 30 news organizations and preservation initiatives. What we found was that the majority of news outlets had not given any thought to even basic strategies for preserving their digital content, and not one was properly saving a holistic record of what it produces. Of the 21 news organizations in our study, 19 were not taking any protective steps at all to archive their web output. The remaining two lacked formal strategies to ensure that their current practices have the kind of longevity to outlast changes in technology. You can read the full report here.

Between about 1950 and 1990 a single media organization handled most of the steps involved in news production, including archiving. At a good number of newsrooms, an in-house librarian was a stop in this production pipeline, guaranteeing some level of future access by clipping individual news stories from the newspaper and filing them on-site according to subject keywords in a morgue (a physical space allotted to the clippings). Back issues of whole newspapers were also frequently kept on-site in multi-story buildings.

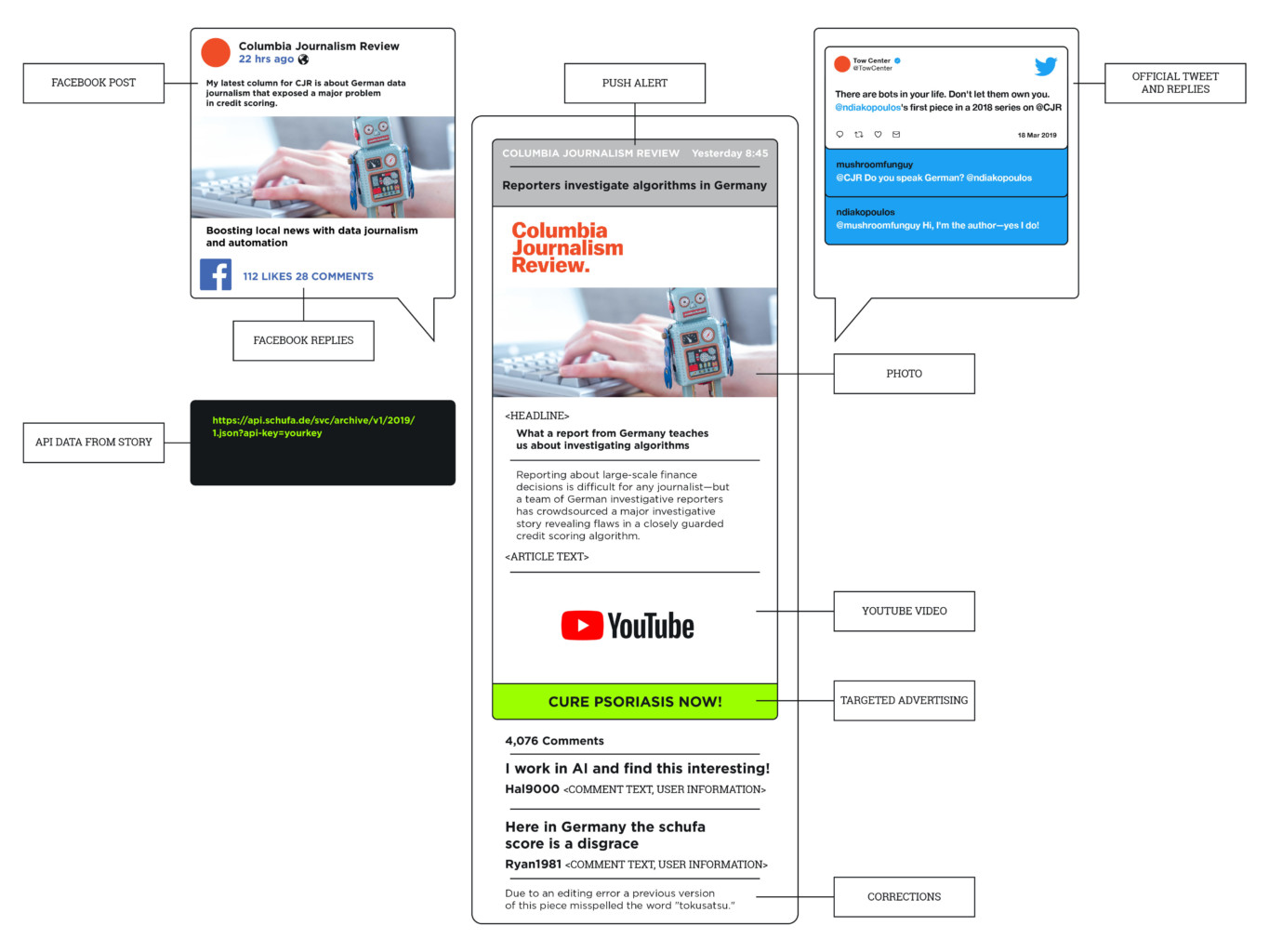

This infrastructure began to break down by the mid-1990s with widespread adoption of the internet and the multifaceted production of online news. Today, a news product often consists of no fewer than a half dozen elements, including a headline, byline, text, and images, as well as comments, interactive features, embedded video, and outgoing links. In addition, a reporter or editor will post links to stories (as well as curated content) on external sites such as Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and other third-party platforms. While the internet has created a vibrant information infrastructure, very little digital content is archived and former models no longer can guarantee long-term access. Although some news workers recognize the risk of losing content, they continue to rely on a content management systems or cloud-based servers to store their work, practices they confuse with preservation and that we argue are not the same.

The news is in danger

The majority of the news organizations that participated in this research (19 of 21) had no documented policies for the preservation of their content—nor did they have even informal or ad-hoc archival practices in place.

In addition to the failure to archive published stories from their own websites, none of the news organizations we interviewed were preserving their social media publications, including tweets and posts to Facebook, Instagram, or any other social media platform. Only one was taking the steps necessary to tackle the problem of archiving interactive and dynamic news applications. Digital-only news organizations had even less awareness than print publications of the importance of preservation. A persistent confusion that backing up work on third-party, cloud servers is the same as archiving it means that very little is currently being done to preserve news.

When we asked interviewees why they believe news organizations are not archiving content, they said repeatedly that journalism’s primary focus is on “what is new” and “happening now.” Journalists (and their news organizations) are more interested in preserving documentation of their reporting and what makes it accurate than preserving what ultimately gets published.

As a result, platforms and third-party vendors, which increasingly host news content on their closed servers, are in control of the pieces necessary for holistic preservation without the journalistic incentive to enact it.

Staff at news organizations often cited relying on the Internet Archive, a nonprofit digital library that maintains hundreds of billions of web captures, to preserve their own publications—even though web archiving has limitations around the formats it can capture and preserves only a fraction of what is published online.

News apps and interactives, in particular, are at high risk of being lost because often the new technologies they are built on become obsolete before anyone thinks to save them. Newsroom developers and emulation-based web archiving tools under development can be valuable allies in preserving these and other resources in jeopardy.

What can be done?

There exist a number of other archiving initiatives by both individuals and nonprofits from whom news managers can learn or enlist services, including PastPages by Ben Welsh, NewsGrabber, by Archive Team, and Archive-It by the Internet Archive. According to news organizations, for digital archiving efforts to succeed, the process must be made simple, both in terms of implementation and workflow.

Partnerships among archivists, technologists, memory institutions, and news organizations will be vital to establishing best practices and policies that assure future access to digitally distributed news content. Collaboration between all parties should begin with two questions: What should be preserved? Who should preserve it?

Creating robust digital archives will mean grappling with tough questions, like how often to capture a copy of an ever-updating home page, if personalized content and newsletters should be preserved, and what to do with reader comments and social media posts.

To enact lasting change, it will be key to find opinion leaders in the field to help introduce archiving ideas in a way that makes sense to staff, as well as to those in management positions who must ultimately be convinced of its advantages and compatibility with their priorities.

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.