Sign up for The Media Today, CJR’s daily newsletter.

Media deserts, ghost newspapers, parachute coverage that only dips into communities in moments of tragedy or disaster: Discussions about the crisis in local news tend to be framed in terms of absence, and as many local news outlets close or are gutted by their owners, this is understandable. There are clearly structural problems funding and sustaining local news. But in speaking with Philadelphians about how they get news about their communities, some alternate narratives emerge: stories of existing channels of communication and of places where a wealth of local knowledge circulates, albeit unevenly.

Over the past several months, we—four fellows at the Tow Center for Digital Journalism— explored two different areas in the Philadelphia metro area: Germantown, a majority African-American neighborhood in northwest Philadelphia, and Montgomery County, a sprawling, majority-white, politically divided suburb of Philadelphia. From November 2017 to February 2018, we conducted a study examining residents’ news practices and attitudes toward media. We then organized a series of workshops for study participants, community leaders, and journalists to generate ideas to address the challenges raised by the study. We asked them, How can journalists and community members build trust and have more constructive, collaborative relationships?

Workshop participants reminded us that community information needs sometimes have little to do with the priorities of traditional media. Several people suggested connecting residents to each other through newsletters or other kinds of online and offline outreach. And participants from communities that felt misrepresented emphasized the responsibility of legacy media to learn the history of communities and work to repair relationships

This effort follows the model first tried by Tow Center for Digital Journalism fellows Andrea Wenzel and Sam Ford in Kentucky.There, a research study followed by a workshop led to the development of several engaged journalism pilot projects, such as a community contributors program that reimagined the rural tradition of “society columnists.” We knew these specific projects—which were built on community traditions—would not directly suit the needs a neighborhood in Philly. But we wanted to explore whether the process of assessing community needs and then engaging members to address them was portable, and what would emerge from transposing it to urban and suburban Philadelphia.

A participatory process

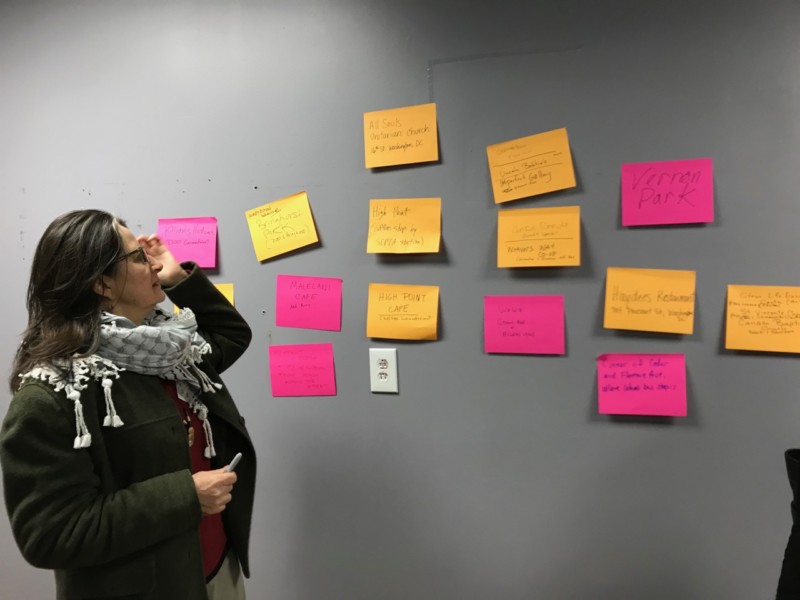

For two Saturdays in a row, our research team organized workshops—first in Germantown, then in Montgomery County. At both, we gathered area residents, leaders of community organizations, local business associations, representatives of universities and student media, and journalists from local newspapers, public and community radio, and television.

We began each workshop sharing key findings from the focus groups, story diaries (in which participants logged stories that captured their attention and how they shared them on and offline for a week), and interviews we conducted with residents. These included reflections from Germantown residents, whose distrust of media long preceded post-2016 concerns around disinformation and partisan coverage. Study participants attested that their community received too much disproportionately negative coverage (particularly coverage of crime), but not enough nuanced coverage of issues that affect them personally such as education, gentrification, jobs, and transportation. They attributed inaccurate coverage, such as referring to a crime taking place on Germantown Avenue as being in the Germantown neighborhood when it wasn’t, to a lack of experienced journalists and a lack of journalists from their community—as well as to sinister and deliberate financial or political motives.

In Montgomery County, study participants put a greater emphasis on local news gaps—with several referencing the consolidation of ownership of several local newspapers and a resulting thinning of local coverage. They also reflected partisan patterns in what constituted trust. While most emphasized a need for accuracy, right-leaning participants put greater emphasis on the need for media to strike a respectful tone to be trustworthy.

Despite their differences, there were commonalities between the residents’ wishlists in both areas. These included wanting more coverage that explored attempted solutions to local problems and constructive initiatives in the community, opportunities for media to work with communities to create coverage, and an openness to media facilitating discussion on community issues.

To help us brainstorm how these wishes could be fulfilled, we invited leaders of engaged journalism and solutions journalism initiatives around the US to join our workshops. We heard lessons learned from representatives of Free Press’s News Voices, the Listening Post Collective, Your Voice Ohio, and Resolve Philadelphia. We then transitioned to small groups with combinations of journalists and community stakeholders to brainstorm ideas that would respond to concerns and push toward possible interventions.

A workshop participant at a session in Philadelphia. Photo: Andrea Wenzel

Connecting to community

As participants brainstormed possible ideas that might help strengthen the connection between communities and media, there were a few recurring themes. One potential advantage in both areas was the power of existing informal networks: This included neighborhood Facebook groups and community newsletters, as well as community organizations, churches, and historical societies.

In Montgomery County, one participant ran a newsletter about community happenings to which several other participants subscribed. She explained that, after setting up tables at local farmers markets, they now had a 4,000-person-strong mailing list.

Newsletters and other non-traditional media were also referenced in the Germantown session. One participant suggested that journalists needed to pay more attention to the “value of connectors”:

“A lot of news goes on underground. There are people who know about it, but it doesn’t get distributed in ways that those of us who are actually working in the media see, and how do we get plugged into those networks? How do those networks plug into us? That’s where the role, that’s where connectors can come in, and our challenge is to sort of like find them, get them involved, or at least willing to share.”

A Montgomery County participant similarly suggested, “There are people who know what the issues are that the journalists could connect with, and they already have that deep knowledge.” In Montgomery County, considerable discussion was devoted to the question of whether citizens could fill the gap of coverage of local council and school board meetings. As a local newspaper reporter explained, given his mandate of coverage in a shrunken newsroom, it was impossible for him to be at every meeting. Participants suggested possible adaptations including collaborating with an area college and/or a local civic group such as the Rotary Club to train citizens and students to do basic reporting, or possibly exploring citizen documenting models a la City Bureau.

ICYMI: In Pittsburgh, editors won’t let an editorial cartoonist criticize Trump

Several participants discussed the need to train and support citizen journalists. As a Montgomery County participant said:

“You have to support residents. Maybe that’s giving them information so that they can, so they know that there even is an issue in their community. Enable them so that they can work towards solutions. Connect them with media and with other folks who would be interested.”

Participants discussed a range of possibilities around training and payment for community contributors.

In both locations there was an emphasis on valuing the communication resources already present in communities. From local influencers and connectors to community organizations, participants pointed to a range of ways community members were stepping up to share information that mattered at the hyperlocal level, if not necessarily to city-wide media. However, they also argued that this information did not circulate evenly within communities and there was a need to make connections between these resources to expand access to community information.

In addition, as larger news outlets looked to connect with community members, a media representative suggested they should take care not to restrict themselves to a limited number of self-appointed spokespeople: “We have to keep going deeper in terms of our sources.”

A lot of news goes on underground. There are people who know about it, but it doesn’t get distributed in ways that those of us who are actually working in the media see, and how do we get plugged into those networks?

Fair & contextualized representation

Another theme, particularly in Germantown, was that media outlets needed to not only represent their community more fairly and in a less stigmatizing way—but also in a way that acknowledged history and context. As one community member argued, “a journalist should step correct when they come to Germantown.” Another added:

“We can’t talk about where we’re going now and what we’re going to do in the future without always grounding ourselves in the history. Because if you do that…you’re starting in the middle without the context.”

For example, coverage of issues such as gentrification should include “how a place became what it is today”—acknowledging a history of racist housing policies and practices.

A media outlet representative suggested that journalistic practices at times contributed to a neglect of history:

READ: With Bundy story, the national media slowly learns how to cover the American West

“Journalists sometimes have a habit of going and talking to sources because [they] know what side [those sources are] on. We don’t leave room for [the source] to share the perspective for history …We say, but we hear you’re against this. What are your thoughts on this issue? So, just by that approach to reporting, we’ve already created a gap as opposed to giving someone an opportunity to tell their story.”

Another participant noted how a lack of veteran reporters in a newsroom contributed to this history gap. Participants shared ideas for addressing the gap, ranging from holding community history roundtables, to connecting new reporters to existing community groups and historical centers, to getting personal stories from elders at senior centers.

Accountability conversations

A considerable measure of conversation in both communities focused on how to connect residents of those areas to one another, allowing them to access the basic community information they needed to participate in civic and social life. At the same time, there was a recognition of the power and influence of larger regional legacy media, such as the Philadelphia Inquirer, local television networks, and other city-wide outlets. As one community advocate pointed out regarding the stigmatization of Germantown, “hyperlocal news can do a lot about trying to change those perceptions, but it is legacy media that shapes the narrative.”

A participating journalist suggested that legacy outlets were genuine in wanting to build better connections with communities: “I think they need to do a better job of telling people that, and sort of explaining that they’re on this road, and they understand that they, you know, kind of need to repair relationships particularly in communities like Germantown.” She suggested that this might be assisted through two-way channels of communication that focused on accountability:

“So, talking, getting feedback, trying to do your reporting better. Then coming back again, you know, six months later and saying, how did we do? What can we do better? Where did we screw up? So, having that kind of continuous dialogue.”

Next Steps

Following these two workshops, we shared our findings at the Northeastern Society for Professional Journalists conference held in Philadelphia. There, workshop participants representing WHYY, Resolve Philadelphia, and community advocates from Germantown and Montgomery County reflected on how to strengthen relationships between communities and media.

These workshops were just a first step. Initial conversations between journalists and community advocates are beginning to explore possibilities to create projects that increase communication and deepen understanding between media and communities. These may include creating structures for regular accountability conversations, using engagement platforms to connect existing community influencers and organizations, and creating training and community outreach collaborations between universities, media and community stakeholders.

The path forward is certain to be a bumpy one given the histories and power dynamics that must be navigated, and the contemporary structural and financial challenges facing local journalism. That said, in these two communities, many participants recognized that news media and communities can be “on the same team,” even if they haven’t historically behaved that way. And a good starting place is recognizing and building connections between existing communication assets.

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.