Sign up for The Media Today, CJR’s daily newsletter.

Last summer, the Shambhala Buddhist community was stunned to learn that its leader, Sakyong Mipham Rinpoche, had sexually assaulted numerous female students. The story was not broken by any of the several Buddhist news outlets, but instead by Andrea Winn, a former Shambhala member and survivor of sexual abuse who conducted her own investigation.

Winn, the creator of Buddhist Project Sunshine, does not consider herself a journalist. But she was able to get many other survivors to tell their stories, ultimately shining light on decades of abuse by faith leaders throughout the community. When reporters descended upon the story—requesting additional proof, corroboration, and on-the-record interviews—everything changed. Many survivors were wary, exhausted by their trauma and unwilling to put their names out for public scrutiny. The ensuing struggle between the goals of journalism and the needs of survivors underscores both the benefits and limitations of reporting on sexual abuse. Journalists often say they do not decide the consequences of the news they report. Perhaps Buddhist Project Sunshine points to another way.

NEW: Borders are imaginary. News coverage should treat them that way.

A BRANCH OF TIBETAN BUDDHISM, Shambhala is a community founded by Chögyam Trungpa and now led by his son, Ösel Rangdröl Mukpo, also known as Mipham J. Mukpo or Sakyong Mipham Rinpoche. Shambhala International, the community’s governing organization, is headquartered in Halifax, Nova Scotia, and runs about 200 meditation centers around the world.

The roots of Winn’s project date back to her childhood in the Shambhala community, when, on several occasions, she was sexually abused by other members and one Shambhala leader. Winn didn’t speak about that abuse for years, but she saw it happening to other women, and knew the problem was widespread. When she raised concerns around 2000, she says, she was forced out of the community. (Winn still practices Shambhala on her own.)

In 2016, Winn suddenly felt like she had broken a Buddhist vow by “giving up” on the community. “From the beginning, I was trying to be a good Buddhist,” Winn says. “I constantly tried to come from a place of peace.” In February 2017, she began organizing a year-long initiative, which she called Buddhist Project Sunshine, to help Shambhala heal from years of sexual violence. She hoped to gather female Shambhala leaders together for collective discussions. When that didn’t pan out, she thought she might collect anonymous statements from survivors and submit them for publication at the Shambhala Times, an online community magazine. But no one came forward. With her self-imposed project deadline approaching, Winn began writing a report about her efforts, even though she felt they had failed.

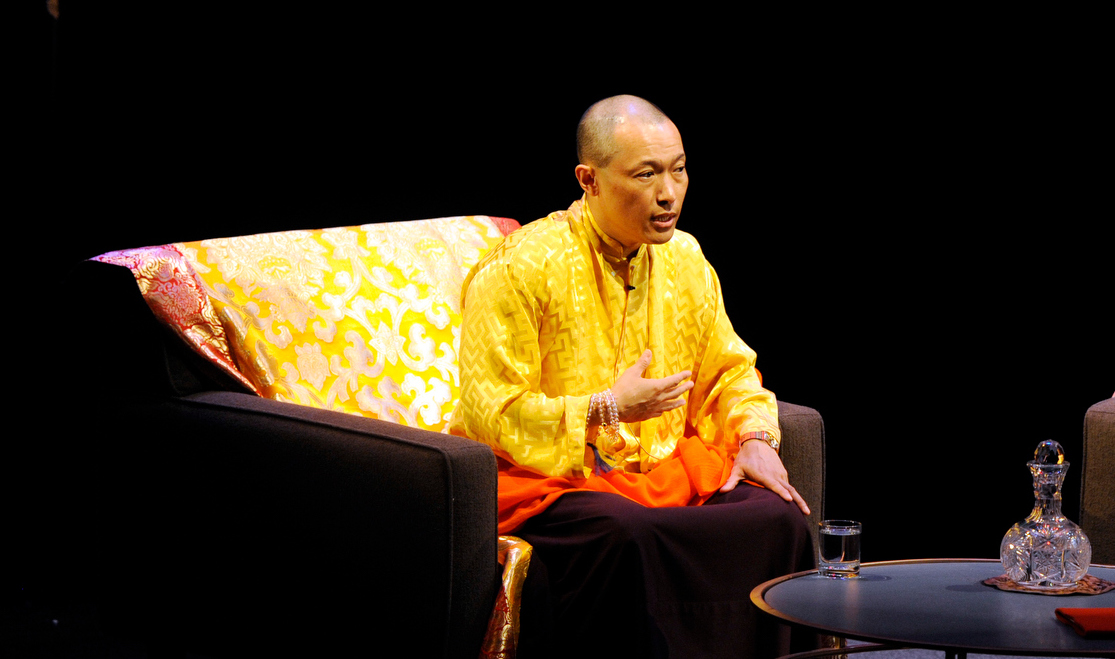

Andrea Winn, founder of Buddhist Project Sunshine. Photo courtesy of the subject.

Mid-January 2018, as the #MeToo movement gathered steam, something changed. “All of a sudden, people just started to come out of the woodwork, wanting to write anonymous impact statements,” she says. Winn scrambled to include some of the statements in her report, which she published on her personal website on February 15, 2018. The report included statements from five anonymous survivors, detailing sexual abuse by teachers in the community and Shambhala’s lack of institutional response.

The report made a big splash, particularly in Shambhala groups on Facebook. Winn received a flurry of messages and emails from critics as well as survivors, some of whom had new stories to tell.

Winn also heard from Carol Merchasin, a retired employment law partner at the law firm Morgan Lewis. Merchasin, who had experience investigating workplaces, hoped to lend credibility to Winn’s project. “I said, ‘You need to have more detail if you really want to have people believe you,’” Merchasin tells CJR. She joined Buddhist Project Sunshine as a volunteer, producing two investigative write-ups for the project’s “Phase 2” and “Phase 3” reports, published in June and August of last year, respectively.

Before they published the Phase 2 report, Winn and several other Buddhist Project Sunshine volunteers watched the movie Spotlight, which tells the story of Boston Globe reporters uncovering decades of sexual abuse and cover-up in the Catholic church. “It was kind of like, we were the ones doing this,” Winn says.

Unlike the journalists in Spotlight, however, Winn insisted that survivor statements remain anonymized in the reports. “It was not about addressing specific situations,” she explains. “It was not about getting justice about specific situations. It was about raising awareness.”

BUDDHIST PROJECT SUNSHINE’S FINDINGS began to attract attention from journalists after the first report. But it was the second report, which implicated Shambhala’s leader, Sakyong Mipham Rinpoche, that brought a flood of coverage by mainstream outlets including The Canadian Press and The New York Times.

Throughout the process, Winn acted as a gatekeeper, protective of the survivors who had shared their stories for her reports. She says she felt betrayed by some journalists who she believed didn’t put survivors’ needs first in their reporting.

Jerry West, a producer at CBC Radio, declined to run a story about the Phase 2 report without an interview from one of the survivors. Winn says she wasn’t able to provide him with such an interview. “He didn’t get the fact that these women had been sexually abused and spiritually abused by their guru, and had been shunned from the community,” Winn says. “His expectations were outlandish.”

West says he had already interviewed Andrea for a story about the Phase 1 report, and he needed new sources willing to go on the record to move the story along after Phase 2. “I can’t just read a report into the record,” he says. “We need a live person to talk.” West says he still wants to run another story about the sexual abuse in Shambhala, but hasn’t yet found another source willing to go on the air.

Wendy Joan Biddlecombe Agsar, a reporter at the Buddhist magazine Tricycle, asked Winn if she might speak to a specific survivor mentioned in the Phase 2 report. Winn asked the survivor if she felt comfortable speaking to a reporter, but the woman, referred to as “Ann,” said she wasn’t up to it before the Phase 2 report came out. Agsar ultimately published her story on the report with a note that Ann “declined to speak with Tricycle about her accusations.”

“It simply isn’t ethical for me as a journalist to not attempt to reach out to anonymous accusers in a story about widespread abuse…and to omit the fact that I attempted to reach out,” Agsar tells CJR. “I’m reporting a story, not just relaying the information that Winn wants me to tell our readers.”

Winn, who was outraged by that sentence, has a different take on journalists showing all of their work in finished stories. “The last thing [the survivors] needed was Tricycle saying that Ann declined to make a statement,” she says. “When I hear that on the news, I think, Well, what do they have to hide?”

We’re reporters, we have to corroborate things, we have to keep a level of independence. But it’s not a process that’s designed around helping people heal.

FOR MANY SURVIVORS, the recent deluge of sexual abuse journalism has brought welcome and overdue recognition of the pervasiveness of sexual abuse. But the relentless press coverage has also created a new kind of trauma. Headline after headline has thrust alleged abusers into the spotlight, all the while commodifying the pain of survivors. Journalists covering sexual abuse are encouraged to use extra care and follow certain best practices, but there are still limits to how journalistic institutions, which are themselves centers of power, can confront the full scope of sexual abuse and its effects.

While the Phase 2 and Phase 3 reports were being published, Buddhist Project Sunshine also established a support network for survivors and other members of the community to process the news. “It was always supposed to be about more than just exposing abuse,” volunteer Katie Hayman, a trained spiritual care practitioner who helped to lead moderated discussions among community members on Slack, says. Before new reports were published, moderators received extra preparation and training to help the community receive the news. They considered questions such as, “How do you respond to the aftershock and care for the people who are reading that news and are going to be devastated?”

Hayman believes Buddhist Project Sunshine’s survivor-centered approach enabled many women to come forward. “It was a different way of doing things that didn’t just take their stories and forget about them,” she says. “You would give your story and they would continue to care.”

“I honest-to-God wish we had something like this in our community,” Hayman, a practicing Roman Catholic, adds. “Because I saw the way that people were heard if just given the space.”

JOSH EATON, an investigative journalist at ThinkProgress, was one of the first reporters to write about the allegations raised in the first Buddhist Project Sunshine report. “I really feel like Josh Eaton getting involved made all the difference,” Alex Rodriguez, a former Shambhala member and a volunteer with BPS who coordinated press relations, says. “But Josh Eaton got involved because Andrea took the first step.”

Eaton, who also has a masters in divinity from Harvard with a focus on Buddhist Studies, treated the stories with care, according to Rodriguez. Nevertheless, Eaton says his goals were always journalistic. “We’re reporters, we have to corroborate things, we have to keep a level of independence,” he says. “But it’s not a process that’s designed around helping people heal.”

Winn says she would have welcomed the work of a journalist earlier on in the process, someone to bring all of the wrongdoing to light in the first place. “I took a lot of responsibility in this,” she says. “It would have been really nice for me to have somebody else taking the lead, like to have a true partner or someone to be the knight in shining armor for me, or for us.”

But it’s unclear whether the story would have been the same. The fact that a survivor from the Shambhala community led the original investigation made all the difference, according to Rodriguez.

“[Winn] never pretended to be providing objective information. She came into this from a place of believing that by speaking her truth she could contribute to community healing,” Rodriguez says. “Had a journalist been catalyzing it, I don’t think you would have gotten the same impact.”

ICYMI: Wa Lone and Ka Soe Oo are free

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.