Sign up for The Media Today, CJR’s daily newsletter.

On Monday afternoon, Mariel Padilla, a master’s student at Columbia Journalism School, sat around a table with classmates, listening to Professor Giannina Segnini lead a discussion about email encryption for reporting across borders. A couple floors below, journalism bigwigs and other members of the press crowded into the World Room, an ornate, high-ceilinged chamber reserved for the event, eager to watch Pulitzer Prize Administrator Dana Canedy announce this year’s winners. For Padilla, who moved to New York last year from the small town of Oxford, Ohio, just being in geographic proximity to the announcement was a thrill.

“I knew I was going to be two floors above where it was happening,” she says, reflecting on the moment, “and I remember thinking, Oh, that’s cool, I can tell people that I was in the same building [where] the Pulitzers are being announced!”

Little did she know she was about to become a Pulitzer winner herself.

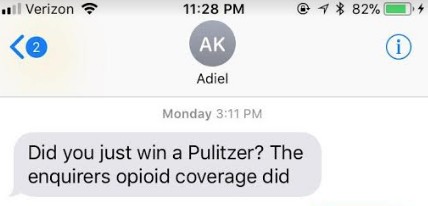

In class, Padilla was typing notes on her laptop when a text bubble popped onto her screen. It was from a friend, Adiel Kaplan, sitting across the room.

The summer before starting her program at Columbia, Padilla interned at The Cincinnati Enquirer. She got her start in journalism the year prior in a reporting class at Miami University Ohio, publishing hyperlocal stories on the drug crisis and its impact on children.

But this was no ordinary summer at the Enquirer. As the 60-person newsroom reported an ambitious story chronicling a week in Cincinnati’s heroin crisis, Padilla, who had decided to pursue a career in journalism just two years prior, found herself at the center of what would become Pulitzer Prize–winning local reporting.

ICYMI: A pretty bad typo in the LA Times

A breaking-news intern with a penchant for crime reporting, Padilla, 23, was tasked with visiting the county jail each morning during the project’s week of coverage to sort through hundreds of paper arrest slips and flag opioid mentions. From there, she took it upon herself to create a spreadsheet for Enquirer reporters, documenting the time, location, and nature of every opioid-related arrest that occured over those days.

The Enquirer had reporters booked around the clock. “It was a full-newsroom effort, that was the insanity,” Padilla remembers. “There were two or three people just in charge of managing the schedule. There would be people scheduled from, like, 4am to 10am. It was very intense.”

At the end of the project, despite dogged 24/7 reporting, there were gaps in coverage, especially in the late-night hours when the city slowed. Padilla’s database became a go-to for filling in those gaps, allowing the narrative to stretch uninterrupted, and revealing the rhythmic, ticking heartbreaks of an epidemic that does not sleep.

Published in September 2017, the story, “Seven Days of Heroin,” prompted a nationwide conversation about the opioid crisis, reflected in newsrooms around the country.

Sitting in class, more than 500 miles from the Enquirer newsroom and with nearly a year having passed since her internship, the story felt disconnected from Padilla’s new life in New York. “I haven’t really been keeping up with nominations, so I didn’t even know it was nominated,“ Padilla remembers, “CJR did a piece right after the story came out, so I knew then that people were saying it could win a Pulitzer, but people say that about lots of things.”

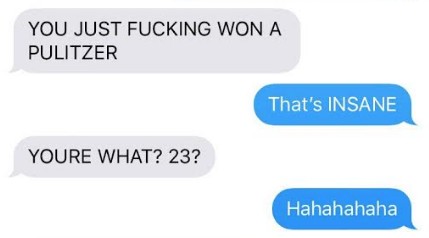

Even when she found out the Enquirer had won, she wasn’t sure she would be included in the list of prizewinners. But another text from Kaplan popped up:

And then a text from Padilla’s editor last summer, Bob Strickley, confirmed:

“I was in shock,” Padilla says. “My eyes just went so wide and I’m pretty sure my mouth was open. Obviously, I couldn’t make noise or anything because my professor was still talking.”

The classroom stayed quiet, but the news spread quickly around the table. “No one is supposed to be on their phones, but we have our laptops, so other students in class started messaging each other and finding out,” she says. It wasn’t until the class break that a classmate stood up and announced it.

Despite the exchange of glances around the room, and what classmates have described as a “hilarious” expression on Padilla’s face, Professor Segnini, who was absent during the break, didn’t notice. It wasn’t after class that she heard the news and sent out a congratulatory email.

“We kept talking, class was regular, I didn’t notice anything was happening,” Segnini says, reflecting on Monday’s class. “Why on earth did no one just say it loudly? If it was me, I would have totally disturbed the class. I would have caused a big mess! It’s a big deal!”

Winning a Pulitzer while in journalism school is like winning a Grammy while you’re still in the high school choir. Padilla’s classmates joked, she says, about whether she even needs to be in journalism school, “but [that was] definitely never a thought in my mind,” Padilla says. “I mean, I technically am a Pulitzer winner, but I am just so humbled by the fact that they put the interns on the byline. I feel like I still need to learn all the things that I’m learning, which I think is why my general reaction was just straight shock. I still don’t believe it.”

Padilla’s life-changing experience as a young reporter at the Enquirer is just one of many merits of local newsrooms, which have historically served as an entry point for aspiring journalists. “My experiences at the Enquirer [were invaluable and] prepared me…to be here,” she says.

That preparation certainly paid off. “She has an ability to integrate journalism and technology—that doesn’t happen very often,” says Professor Segnini, who directs the data journalism program at Columbia. “She knows exactly how to find a story out of data and ask the right questions; that’s one of the most important skills.”

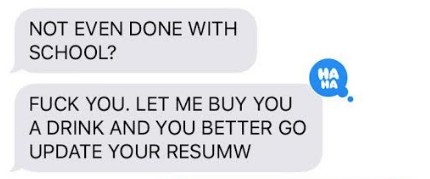

Following the big news on on Monday, Kaplan insisted they celebrate, but with graduation less than a month away and the professional hereafter on everyone’s mind, the invitation came with a friendly reminder:

ICYMI: Lawyer behind Hannity revelation at Cohen hearing speaks

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.