Sign up for The Media Today, CJR’s daily newsletter.

Gretchen Carlson is crying as the crown is placed on her head. Her bottom lip is a just-slightly-off-center parabola. Eyes closed. Neck muscles strained from shuddering relief. She won.

Some Miss Americas, like 2018’s Cara Mund, gasp in surprise when they win. Their eyes and mouths form perfect circles of shock and wonder. But Carlson isn’t surprised. She deserves this. She’s worked hard for it. Writing in her 2015 memoir, Getting Real, Carlson recalls that, in the moment, “the sense of relief was so intense—almost impossible to describe.” Days after her win, in an interview with CNN’s Jack Cafferty, Carlson would refuse to describe herself as lucky. She writes, “I think he had the idea that you just walked out on a stage, flashed a pretty smile, twirled, and took your chances. I assured him that luck didn’t get me there. I worked my butt off for that opportunity.”

Her whole life had been about this—not Miss America specifically, but about achievement, about being the best at whatever she did. Since the age of six, Carlson trained to be a solo violinist—performing with the Minnesota Orchestra at 13 and attending the Aspen Summer Music Festival to study with Dorothy DeLay, the renowned instructor—while still making the honor roll. And that was just middle school. In high school, Carlson won her first pageant, Miss T.E.E.N. Minnesota. She starred in “South Pacific,” performed in “The Whirlwinds,” a singing and dancing troupe, and got into Juilliard. Ultimately, she went to Stanford. Her yearbook calls her a “star.”

Three years ago, after 11 years of working for Fox News, Carlson filed a lawsuit against Roger Ailes, accusing him of sexual harassment. The lawsuit ended with Ailes’s ouster and a $20 million settlement for Carlson. In the wake of that fight, Carlson was declared a hero and has since built her brand as a #MeToo pioneer, asserting herself as the woman who started the movement. (Actually, the Me Too movement was begun in 2006 by an activist named Tarana Burke.)

A documentary on Lifetime, Breaking the Silence, depicts Carlson as a champion of women. In the film, Carlson uses her story to set herself up as a kind of Chris Hansen for sexual assault victims. That is, if Chris Hansen were your midwestern mom and wore ruffly blouses while demanding justice. She’s also on the frontlines to end forced arbitration clauses in employee contracts.

ICYMI: The mystery of Tucker Carlson

There is also a movie, out in December, directed by Jay Roach and starring Nicole Kidman as Carlson. And there is a Showtime series out in June based on Gabriel Sherman’s The Loudest Voice in the Room (2014), in which Carlson will be played by Naomi Watts. Each one positions Carlson as a type of hero.

It’s a crown that Carlson has eagerly grasped. Her 2017 book Be Fierce, written in the aftermath of her Ailes lawsuit, offers tips for women facing workplace harassment, telling them to document offenses, speak up when they see problems, and be ready to sue. Section headings encourage women to be “badass.”

It was in this newly formed identity as a feminist hero that Carlson became board chair of the Miss America Organization, in January 2018. In her new role, Carlson vowed to reform the pageant into a modern institution of girl power. But it’s turned into a disaster. A recent lawsuit brought by one of the board members against Carlson, rips through the artifice of change and glamour and reveals the problems with an easy, corporate brand of feminism seeks to reform without actually changing anything.

Carlson became MAO board chair after HuffPost published an article detailing the derogatory comments made by Sam Haskell, the CEO of the Miss America Organization, and other board members about former winners of the pageant. In the emails, the lead writer of the pageant telecast, Lewis Friedman, calls former Miss Americas “cunts” and Haskell replies, “Perfect…bahahaha.” Haskell also makes insulting comments about their weight. The emails were leaked to Yashar Ali, a friend of Carlson’s who contributes to HuffPost. Soon, Haskell was out and Carlson was in. She brought in Regina Hopper, who was Miss Arkansas 1983 and a former CEO of the Intelligent Transportation Society of America, as the new MAO CEO.

Together, Carlson and Hopper hoped to take America’s most regressive institution and make it feminist. There was only one problem: not everyone agreed with Carlson’s approach. There was a lawsuit over Carlson’s leadership, which has been withdrawn due to lack of funds, but the pageant Carlson has vowed to save is in danger. And who gets to be crowned a #MeToo hero in the media hangs in the air.

On the surface, Carlson seems like a contradiction—a progressive traditionalist—but such is the push and pull of Minnesota, where she is from. It’s a place of deep incongruity—a state that has elected Jesse Ventura as governor, Michele Bachmann to Congress, and Paul Wellstone and Al Franken to the Senate. Bachmann, who was Carlson’s babysitter, pushes a narrative of home and family, but is herself a successful, ambitious woman. If she were entirely traditional, she wouldn’t have been an ambitious politician. But if she had espoused the totality of her ambition, she wouldn’t have been as traditional as she is. That is Minnesota.

Carlson attended Stanford. From there, she studied abroad at Oxford, but came home to compete in the Miss Minnesota pageant. By 1988, the pageant rules had changed, making talent account for 50 percent of the scoring. And Carlson had a talent, which was playing the violin. She won Miss Minnesota and headed to Atlantic City, where she was crowned Miss America 1989, edging out the favorite, Miss Colorado.

The screenwriter William Goldman was one of the judges, and wrote about the experience in his entirely sexist book Hype & Glory (1990). Goldman calls the contestants “cuties,” dubs Carlson “Miss Piggy,” and imagines Miss Mississippi’s inner life as begging a “big daddy” to take her “all the way down.”

It’s brutal, and Goldman is not just attacking Carlson, he’s the voice of a system that auctions women off for parts. During her reign as Miss America, Carlson appeared on the gag show “Bloopers and Practical Jokes,” hosted by Dick Clark and Ed McMahon. The gag was that she was supposed to be introducing a gadget to a group of executives in Washington, DC, without any preparation or even a clue as to what the gadget was. She was given hints and a cue card until the cue cards are dropped. It was a dumb segment. But Carlson navigated her way through it. She was cool. A few nervous laughs, sure. But she handled it, winning Clark and McMahon’s begrudging respect.

That was the moment when Carlson decided that she would be a TV anchor. She set out to achieve this goal in the same way that she’d set out to achieve every other one, with persistence, planning, organization, and intel. Before she returned to Stanford, Carlson met with a television executive to ask for advice. He was helpful. He took her out to dinner. Later, in the back seat of his car, he grabbed Carlson and stuck his tongue down her throat. She jumped out of the car and ran the rest of the way to the friend’s apartment where she was staying.

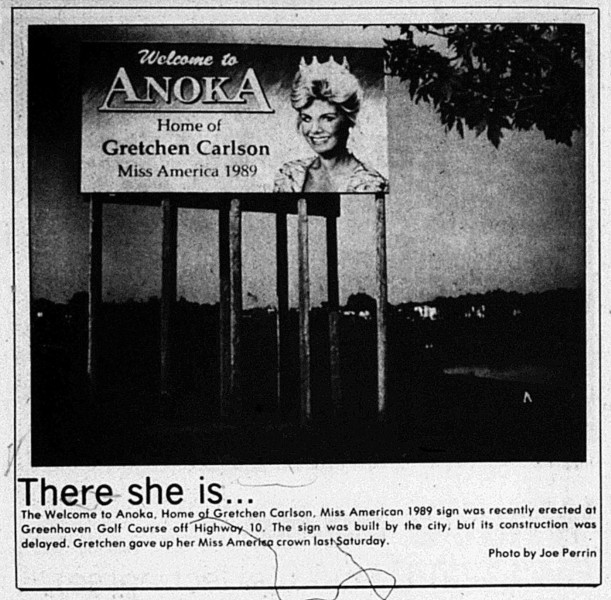

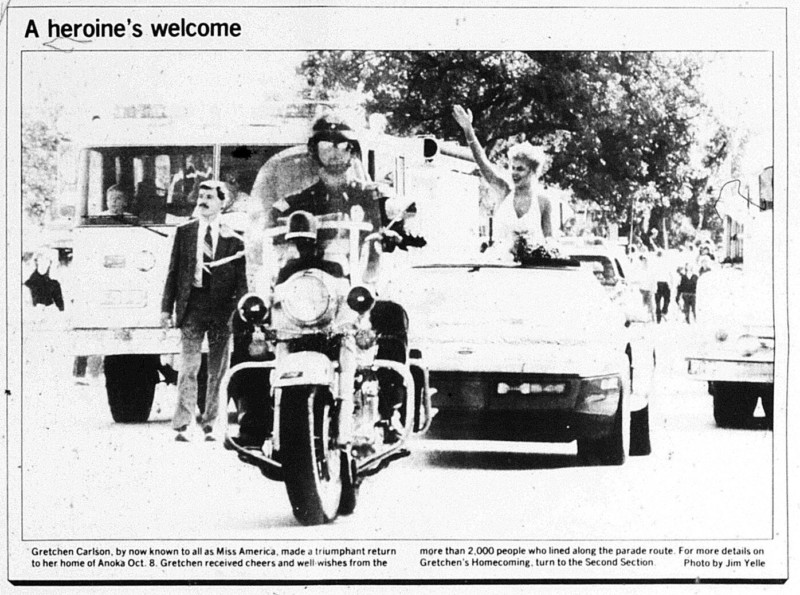

Gretchen Carlson rides in a parade in her hometown of Anoka, celebrating her 1989 Miss America win. Image via Anoka County Union.

A few months later, it happened again, this time with a PR executive who slammed her face into his crotch before they went to dinner. Carlson writes about these moments in her 2015 book, noting, “These men were just too powerful. I imagined myself being characterized as a tease, a liar, and worse, and I was frozen with terror.”

Carlson was eventually hired by WRIC-TV in Richmond, Virginia, as a political reporter covering state executions and the Chuck Robb scandals. Once, Carlson thought that she had a “deep throat” source on the Robb story and met him in a mall. But he ended up stealing the station’s mic and making a clean getaway. She moved on to Cleveland, a bigger market, working for WOIO and WUAB. There, she was a morning anchor along with Denise Dufala, who remembers her as a hardworking and tenacious reporter. In a story about airplane safety, Carlson simulated a plane crash and crawled on the floor of an airplane cabin. She and Dufala were Cleveland’s first all-female anchor team, but the experiment didn’t last. In an interview with CJR, Dufala recalls that the ratings weren’t high enough. Carlson’s contract wasn’t renewed.

Carlson had just married Casey Close, a sports agent who represented Derek Jeter. She scrambled for another job. She found one, in Texas, working as a reporter for KXAS. She covered Columbine, the murder of James Byrd, and Y2K. Within two years, Carlson finally got her big break, at CBS in New York. Marcy McGinnis, a former senior vice president for news coverage at CBS, recalls looking over Carlson’s tapes and being struck by how focused she was as a reporter. McGinnis tells CJR, “[Carlson] is one of those people who you can tell right away that she’s serious, she’s got what it takes. She was smart, she was driven, she knew what she wanted. There was no ambiguity.”

When asked what Carlson was like to work with, McGinnis chooses her words carefully. “Well, working with on-air people is always. . . has its challenges. It’s just the nature of the beast, which is when people are on TV, they have expectations.”

Carlson covered Hillary Clinton’s senate run, the Florida recount, and the September 11 attacks. She eyed an anchor job but, according to McGinnis, there wasn’t one available. So in 2005, Carlson left for Fox. In her 2015 book, Carlson devotes an entire page to how brilliant she thought Ailes was. She called him “sharp and inscrutable” and praised him for being one of the first TV executives who encouraged her to embrace her Miss America status on air.

Jehmu Greene, a frequent commentator on Fox, tells CJR that Carlson “was great to work with. She was a journalist who took her commitment to the truth seriously. It would have been hard for her to counter conservative conspiracy theories on that network and she did, which was a sign early on of her bravery.”

There is a clip from Carlson’s days on Fox & Friends that has received a lot of play in the years since Carlson filed her lawsuit against Ailes. It’s a moment from 2012 when Brian Kilmeade, a colleague, says, “Women are everywhere. We are letting ‘em play golf and tennis now, it’s outta control.”

“You know what?” Carlson asks as she stands up from the Fox & Friends couch. “You know what? You read the headlines, since men are so great.”

When Carlson refers to this moment in Getting Real she says that she was teasing, that the comment wasn’t as political as the media reported when it happened. In 2016, after Carlson filed her lawsuit, Bloomberg News included it in a compilation of the most sexist moments from Fox & Friends. Each moment portrays Carlson as a victim of the sexist Fox News machine—sitting on the couch as guests and her co-hosts make creepy comments about her looks.

What has gotten less air time is her disavowal of transgender rights, or the time she said that LGBTQ rights are a distratction from real concerns, like jobs. Or the times she played into racist fears about Barack Obama being a Muslim, or fed into a fake catfight between Michelle Obama and Hillary Clinton. And there was also her role as a “culture warrior.”

During her time on Fox, Carlson repeatedly editorialized on the persecution of Christians in America. Her most memorable rant was about a Festivus pole, which was put up alongside a nativity scene at the Florida state capitol. Her strident moralizing about faith in America earned her a role in the 2014 movie Persecuted. The movie is a Fox News wet dream of conspiracies: an aggrieved white man, standing up for his faith, is smeared by liberals. It’s a silly movie, but one that Carlson earnestly defends in interviews. And her defense reveals how deeply ingrained her faith is. And this faith explains her commitment to a sense of deep- rooted traditionalism and established systems, even when they don’t serve her well.

Which brings us back to Fox and how, for so many years, Carlson benefitted from a system that she eventually sought to destroy. It’s the same as the fight with Miss America. Carlson, once the winner of the pageant, could deliver its downfall. Will she be a hero then, too?

For a year, Carlson recorded her meetings with Ailes on her iPhone. Her lawsuit alleges that she was kicked off Fox & Friends after complaining about her co-anchors, Steve Doocy and Brian Kilmeade. As a consolation prize, she got her own show. But ratings were low. Her lawsuit alleges that the new show was in a bad time slot and that she was being punished by being denied good interviews and political coverage.

In the lawsuit Carlson says that Ailes told her:

“I’m sure you [Carlson] can do sweet nothings when you want to.”

He asks Carlson how she feels about him, and follows with: “Do you understand what I’m saying to you?”

On September 16, 2015, he told her, “I think you and I should have had a sexual relationship a long time ago and then you’d be good and better and I’d be good and better.”

After Carlson’s lawsuit was filed, more women came forward. Ailes was out. She won.

All of that is ironic, because Carlson herself was the subject of a lawsuit that claimed she too was a bully, lied to the board, and launched an “illegal and bad-faith takeover” of the Miss America Organization. Her legacy as the woman who brought down Ailes made Carlson perfect to reform Miss America, an organization whose cultural moment passed long ago. She was, after all, a former beauty queen, who had succeeded in profession and network dominated by men, specifically a horrible man. And then, she had taken that man down. And yet, her relentless drive, which made her succeed before, is getting in her own way.

According to the lawsuit, filed in December 2018 by a former Miss America board member, Jennifer Vaden Barth, Carlson told the board in early 2018 that ABC refused to air the pageant if they didn’t eliminate the swimsuit portion of the competition. The choice: Miss America could either be on TV or it could have a swimsuit competition. The board picked TV. Carlson went on Good Morning America and made the announcement: no more swimsuits, no more “evening gown” competition. The events were replaced by a red carpet component, where contestants were encouraged to dress in evening wear that represented their style.

ICYMI: I wrote a story that became a legend. Then I discovered it wasn’t true.

The change was widely lauded in the media. It seemed to reflect the #MeToo mood of the country and, of course, Carlson’s personal brand. But in the world of Miss America, the change was like tipping sacred cows. The board hadn’t approved the #MeToo messaging nor had they approved the evening gown component. “We watched and we were just like, ‘Whoa we didn’t agree to that at all,’” a source familiar with the dispute says. “The states weren’t happy. The board wasn’t happy.”

At the time, the board was comprised of seven former beauty queens and two men:

Jennifer Vaden Barth, Miss North Carolina 1991

Gretchen Carlson, Miss America 1989

Jessie Ward Bennett, Miss Arkansas 2001

Heather French Henry, Miss America 2000

Laura Kaeppeler Fleiss, Miss America 2012

Valerie Crooker Clemens, Miss Maine 1980

Kate Shindle, Miss America 1998

Ike Franco, founder and managing partner of Infinity Lifestyle Brands

Ashley Byrd, former president and executive director of the Miss South Carolina Pageant

There were other tensions, too. One day into her tenure as board chair, Carlson began to consolidate power. According to the lawsuit filed by Vaden Barth, the chair of the board was supposed to be a co-chair position. But on January 2, 2018, Carlson sent an email stating that she must “immediately be made Executive Chairperson”—a move that would give her operational control and decision-making power.

The same month, the board voted on the change. Shindle and Fleiss opposed the move, but Carlson and Henry pushed for it. There was a stalemate. So Carlson called Franco, who was at the airport with his family. Carlson rushed the vote so Franco could make his flight. There was no discussion. The measure passed, with Franco as the deciding vote.

Now that she was in charge, Carlson made the board members sign resignation letters that could be executed at any time. Then came the swimsuit feud. In a document filed in support of Barth’s lawsuit, James Lee Exum, president and producer for the Miss Tennessee pageant, claims that, in an email sent on March 28 from Carlson to all the state pageant executive directors, Carlson overstepped. He writes, “While I fully support the intention and goals of the #metoo movement, I was concerned that Gretchen Carlson connected any movement to support the removal of swimsuit. MAO has never joined any movement or political affiliation in its rich 90+ year history because volunteers and leadership have felt it is not a proper connection.”

On May 11, Miss Tennessee 2018 resigned her title by posting a letter on her Facebook page. In it, she expressed frustration with the leadership of the MAO, noting that her time as Miss Tennessee showed her that “I did not and still do not agree with MAO’s management of its personnel and program.”

In an interview, Ericka Dunlap, Miss America 2004, railed against Carlson’s invocation of the #MeToo movement to justify the loss of the swimsuit portion of the competition. “#MeToo has nothing to do with Miss America,” Dunlap says. “Nothing. Not one thing. Unless a contestant uses that as her issue of concern, as her platform issue. #MeToo and Miss America are completely mutually exclusive. Completely. There’s no reason for us to overlap these two movements, organizations, ideals, they don’t coincide.”

Both Exum and Dunlap believe that Carlson was grandstanding. Exum writes that his state was concerned “that MAO would become a driver for Gretchen Carlson’s personal agenda.”

On June 6, 2018, Barth and two other board members called a meeting to address what they saw as mismanagement of the board. According to Barth’s lawsuit, Carlson was fuming. “Carlson went on a 17-minute tirade yelling, berating and belittling” everyone present for circumventing her authority and calling the meeting.

Then something else happened: the board learned that the whole ABC-will-cancel-the-TV-contract-unless-we-end-the-swimsuit-competition story wasn’t exactly true. In the lawsuit, Barth writes that Fleiss reached out to a contact at ABC who said the network had never said the swimsuit portion of the competition needed to be eliminated. The board was ready to riot. Someone told Carlson how mad everyone was. On June 11, she called a meeting.

Text messages sent back and forth between board members the day before the meeting show Fleiss, Shindle, Clemens, Barth, Henry, and Bennett wondering if there might be a conspiracy.

At one point, Ward Bennett weighs in with a text that sounds exhausted: “Y’all is there any way all of this can wait until after miss America. Please don’t take this as me being dismissive because I absolutely am not but this is going to implode the program and I feel a sense of responsibility for pulling this this [sic] off in the next 80 days.”

“[Jessie] perhaps you haven’t heard but there are other dynamics of Regina’s performance that are detrimental and hurting this organization,” Barth texted back. “According to Valerie the office culture is toxic people are scared to death. Cara [Mund] has been belittled and bullied. Is this holding the organization together? Is this doing the right thing For the organization?”

When June 11 arrived, Carlson explained to the board that they had all misunderstood. It wasn’t ABC that was objecting to the swimsuit competition, it was a production company. But her words didn’t help.

“I have no confidence in this leadership,” Barth said during the meeting. Fleiss, too, voiced her loss of trust in Carlson. The meeting was over.

Everything went to hell on June 16, 2018, when a few board members called yet another meeting, over a conference call. According to Barth’s lawsuit, they were tired of Carlson running Miss America like “her own personal fiefdom where she rules as a dictator.”

To stop what members of the board saw as Carlson’s ego run amok, they planned to demand a change of the leadership structure. No longer would Carlson be “Executive Chairperson” with unlimited power. She would be checked. The board would have more oversight. And they had the votes to make it happen. Four board members would have voted to limit Carlson’s decision-making power and return oversight of pageant finances to the board. Three, including Carlson, would have opposed.

What happened instead, according to the lawsuit filed by Barth: Carlson screamed. She accused the board members of “screwing up all the progress she had made.” She was, alleged Barth, “belligerent” and “hateful.”

An attorney for the Miss America Organization, Gino Serra, was on the line. As Shindle called the vote, Serra ordered Carlson to hang up the phone, effectively cancelling the vote.

Four days later, Carlson forced Barth and Valerie Crooker Clemens, Miss Maine 1980, off the board by invoking the resignation letters she had asked them to pre-sign. The next day, Shindle, Miss America 1998, and Laura Kaeppeler Fleiss, Miss America 2012, resigned in protest.

Soon after, Cara Mund, Miss America 2018, published an open letter on her Facebook page accusing Carlson of trying to use the organization to position herself as a leader of the #MeToo movement. She called her a bully. An online petition that garnered more than 23,000 signatures was circulated among state pageant officials calling for Carlson’s resignation. In retaliation, the MAO revoked the license agreements of seven states.

Then Barth filed her lawsuit, claiming that Carlson had “illegally” and “in bad faith” taken over the pageant. She also called Carlson a “bully.” The lawsuit demanded that the court put a temporary restraining order on Carlson’s actions. “If this Court does not voice the illegal and self-serving actions of Gretchen Carlson and Regina Hopper then this symbol of American Culture will be forever lost and will emerge as a lost treasure captive to the whim of a few at the cost to the ocean of volunteers, donors and participants across the United States who are the heart and soul of the Miss America Organization.”

Now, everyone is afraid of Gretchen Carlson. Pageant winners I contacted at the state and local level told me that they feared reprisal if they said anything about her. In an affidavit filed in support of the lawsuit against Carlson, Leah Lasker Summers, the state executive director for the Miss West Virginia Scholarship Organization, claims that she was retaliated against after signing a petition that expressed no confidence in Carlson’s leadership. “I know other states that are not plaintiffs are fearful to speak out given the way the Miss America Organization has retaliated against our organization and others who have spoken out about the actions of the Miss America Organization leadership,” she says.

Barth dropped the lawsuit in March, citing a lack of funds, but the lawsuit was dismissed without prejudice, meaning that the suit can be brought again. The Miss America Organization declared a victory. But the battle isn’t over, not for change and not for women. Like at Fox, Carlson seems to be advocating for change from inside a institution of power. Yet as Carlson remains part of institutions, and remains protected by their power, can she really claim to be a changemaker?

So now, we’re left to grapple with Carlson’s legacy. Not all of our #MeToo heroes will be easy to like. We say we want unlikable women, but when they come to us in real life with their messy complications from inside the institutions that oppress, they confound us, anger us, frustrate us, and surprise us. But in the end, change—in the media and other cultural institutions of power—isn’t possible without them.

CORRECTION: An earlier version of this article misspelled Cara Mund’s name.

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.