Sign up for The Media Today, CJR’s daily newsletter.

Two weeks ago, with the Winter Olympics having just gotten underway in Beijing, L’Equipe, a French sports daily, published an interview with Peng Shuai, a Chinese tennis player who disappeared from public view for weeks late last year after accusing a senior Chinese politician of sexual assault in a social-media post that was swiftly censored. The episode sparked widespread international concern. Peng told L’Equipe that she was grateful for that, but that it had derived from a “huge misunderstanding”; she never accused anyone of sexual assault, she said, and she had never disappeared. “Emotions, sport, and politics are three clearly separate things,” she added, and they should not be mixed up. L’Equipe splashed the interview on its front page, with the headline “WE MET PENG SHUAI” next to a photo that showed Peng wearing a Chinese Olympic jacket and smiling as she looked out the window of a Beijing hotel.

The hotel in question was a base for the Chinese Olympic Committee—and, while L’Equipe boasted that its interview was the first Peng had given to “independent international media” since her disappearance, it took place under circumstances of tight state control. Chinese officials required that the paper submit its questions in advance and insisted that Peng answer in Chinese, via a translator who was himself a senior official; they also insisted that L’Equipe run the interview in Q&A format. (L’Equipe said that it ended up being able to ask other questions that it hadn’t submitted in advance and that it corroborated the translation independently.) The paper acknowledged that it never expected Peng to be candid under such conditions; the goal, Jérôme Cazadieu, the editorial director, said, was to do what the eventual headline suggested—meet Peng Shuai, so that journalists might assess her physical and emotional state, parse her tone, and “tell her that the world has mobilized for her and not forgotten her.” Critics countered that L’Equipe had allowed Chinese officials to use its credibility to launder an exculpatory narrative. Stephen McDonell, the BBC’s China correspondent, wrote that the paper had been “as much involved in a propaganda exercise as in an ‘interview.’”

Listen: Stuart Karle on money and the politicization of press freedom

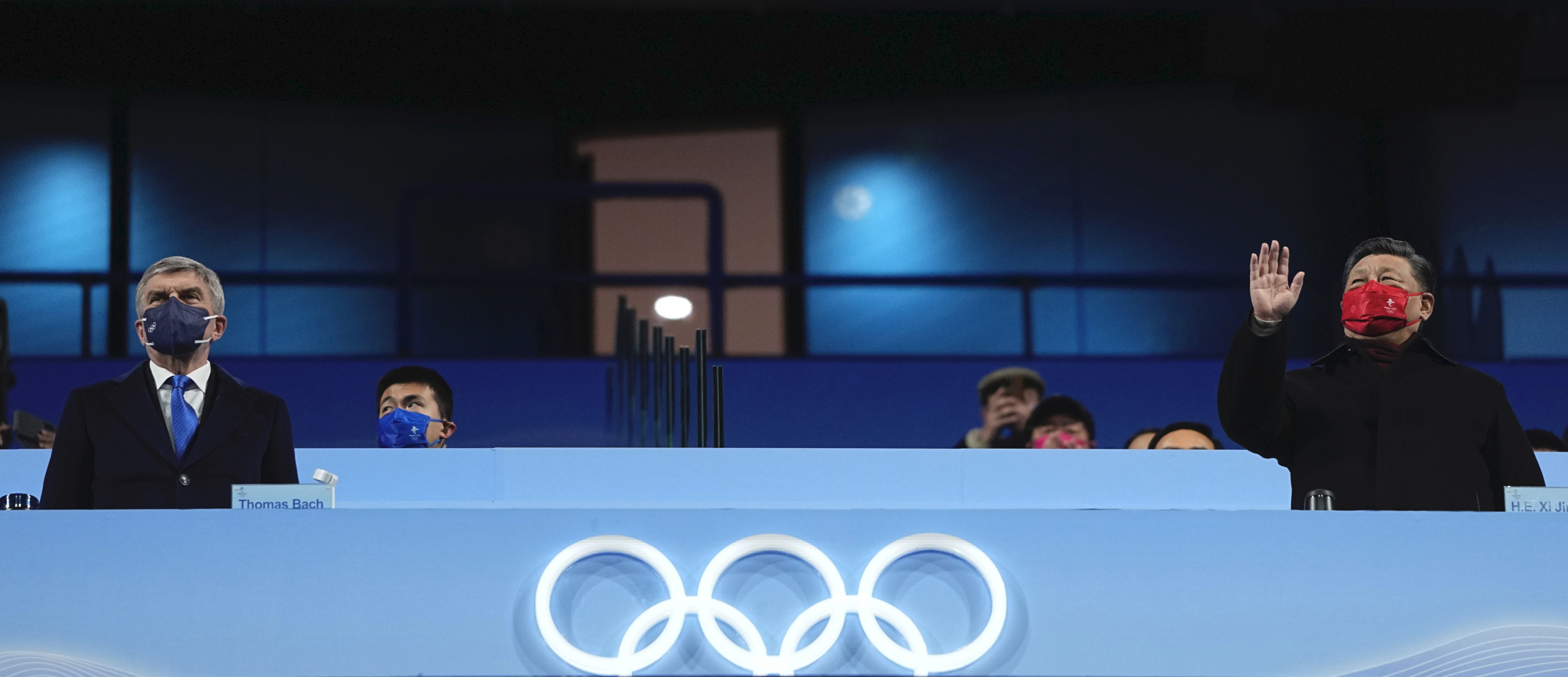

The International Olympic Committee—which has itself been criticized for lending credence to “staged” Peng appearances—said that Peng also met at the Games with Thomas Bach, the IOC’s president. At a press conference, Mark Adams, an IOC spokesperson, referred members of the media to the L’Equipe interview when one asked him whether the IOC had discussed any possible investigation of Peng’s initial allegation of sexual assault. Nor would Adams say whether the IOC believes that Peng is free to speak her mind. “We are a sporting organization, and our job is to remain in contact with her and, as we’ve explained in the past, to carry out personal and quiet diplomacy, to keep in touch with her, as we’ve done,” Adams said. “I don’t think it’s for us to be able to judge, in one way, just as it’s not for you to judge either.”

As Andrew Keh has written for the New York Times, the daily Olympic pressers were often a microcosm of a clash of media ecosystems visible at the Games: non-Chinese outlets would ask “often indelicate questions about what is awry,” including Peng’s situation, while Chinese state media would ask about “all that is well,” like the roast duck in the Olympic village. Foreign reporters faced strict controls on their movement, ostensibly for COVID reasons, with China imposing a “closed loop” system that was successful in constraining the spread of the virus but also had the effect of keeping international media from pursuing hard-hitting stories outside of the Olympic bubble. On the opening day, Sjoerd den Daas, a Dutch TV journalist, was manhandled by security while reporting live on air. The IOC called this an isolated incident.

Chinese state media, meanwhile, leaned into the official push to make the Games a propaganda coup, both at home and abroad. For a domestic audience, state outlets played down China’s sporting failures (as well as American successes) and even framed footage to make the setting look snowier than it was. Chinese propagandists sought to export such messaging internationally, too. They contracted a US firm to coordinate an influencer campaign seeding positive stories of the Games across Western social media. (“They were very clear and I was very clear that it’s about the Olympics and the Olympics only, nothing to do with politics,” the firm’s founder told the Times.) As the Times and ProPublica reported on Friday, they also appear to have weaponized thousands of Twitter bots and fake accounts to a similar end.

As I wrote in this newsletter before the Games got underway, rights groups, including some focused on press freedom, had expressed concerns that China would use the Games to burnish its image while steamrolling criticism of its human-rights abuses in Xinjiang, Hong Kong, and elsewhere; NBC, the official broadcast partner of the Games in the US, came under particular political pressure not to enable such whitewashing, and responded by insisting that it would incorporate geopolitical issues into its Olympics coverage, even if sports would remain its focus. During the opening ceremony, the network addressed some of them and turned to experts, including Jing Tsu, a Yale academic, that it had tapped to offer context. That coverage, however, faced some criticism, with Slate’s Justin Peters suggesting that NBC had couched human rights as a story with two sides, and as the Games progressed, observers, including the Washington Post’s Paul Farhi, noticed far fewer references to geopolitics on the network. NBC disputed Farhi’s characterization, citing, as an example, a report in which Mike Tirico brought up questions about Peng’s freedom to speak freely. Farhi argues that NBC “went no further” than that.

As the Games went on, they came to be dominated, in the wider news cycle, by a controversy tied firmly to the competition. After Olympic officials delayed the medal ceremony in a team figure-skating event that a Russian team had won, Inside the Games, a site that covers what its name suggests, reported that an anti-doping test taken by Kamila Valieva, the team’s fifteen-year-old prodigy, was at issue. Testing officials eventually confirmed that Valieva had tested positive for a banned angina drug in December; arbitrators ruled that Valieva could go on to compete in individual events, but the IOC said that if she placed in the top three, no medals would be awarded. In the end, this would not be an issue; Valieva stumbled and finished fourth. As she left the ice, she broke down and a coach berated her, as the world watched. At a presser, Bach was unusually scathing, describing the scene as “chilling.” Knowing “how the IOC likes to dodge, we came to this press conference ready to have to pry out information,” NPR’s Tom Goldman said. “It was notable that he spoke about her unprompted and in great detail.”

Scolding a coach may fit better with the IOC’s sports-first self-conception than weighing in firmly on behalf of Peng. But here, too, the media atmosphere grew political, and toxic. Duncan Mackay, the Inside the Games reporter who broke the Valieva story, was subject to abuse and death threats, including a warning to be careful about drinking tea, an unsubtle reference to past Kremlin poisoning attempts; British journalists at the Games also reported being confronted by their Russian counterparts, some of whom surrounded a reporter who had asked Valieva whether she took drugs and decried the question as inappropriate. According to Slate’s Yana Pashaeva, Russian state-media figures rushed to defend Valieva, including as a “Russian soldier, fighting for her country” in the face of a shady Western conspiracy. Others defended the coach who berated her, as did Vladimir Putin’s top spokesperson, who called “harshness” an essential ingredient of sporting success.

Chinese state media also downplayed the doping controversy and gave credence, when it was mentioned, to the idea that it might be a US conspiracy—a narrative, CNN’s Beijing bureau concluded, that would seem to reflect China’s growing allyship with Russia as the latter country threatens to invade Ukraine. That threat overshadowed the Games in the global news agenda, despite the conclusion, of many Western analysts and officials, that Putin would stall any invasion until after the Games to avoid doing just that. The closing ceremony was yesterday.

When Peng told L’Equipe that sports and politics should not be mixed, she was echoing a view often expressed by Chinese authorities. US news organizations have expressed a similar view in the past, albeit in a greatly different context. As I wrote beforehand, the idea that sports and politics can be meaningfully separated has always been a chimera, but China’s Games seemed set to pierce the illusion particularly sharply. Didn’t they just.

Below, more on the Games:

- The ratings: The AP’s David Bauder and Joe Reedy write that the Games ended up being a “disaster” for NBC. “Viewers stayed away in alarming numbers, and NBC has to wonder whether it was extraordinarily bad luck or if the brand of a once-unifying event for tens of millions of people is permanently tainted,” Bauder and Reedy report. “Through Tuesday, an average of 12.2 million people watched the Olympics in prime-time on NBC, cable or the Peacock streaming service, down 42 percent from the 2018 Winter Olympics in South Korea. The average for NBC alone was 10 million, a 47 percent drop, the Nielsen company said. That’s even with the average inflated by airing directly after the Super Bowl, a night that brought in 24 million viewers.” (Writing for Slate, Michael J. Socolow had a different take, noting widespread viewership on social-media platforms.)

- Device dangers: Also writing for the AP, Kelvin Chan closes the loop on fears that Chinese authorities would use the Games as an opportunity to electronically surveil foreign visitors, including journalists. Ahead of time, news organizations and press-freedom groups warned reporters to take burner devices to Beijing and exercise digital caution; now that the Games are over, “concerns turn to what malware and other problems those who failed to heed the warnings might be carrying with them,” Chan writes. “Cybersecurity firm Mandiant said there’s been no sign of any ‘intrusion activity’ tied to the Olympics by the Chinese or other governments. But that shouldn’t be taken as a sign that nothing happened” since most such activity is detected a while after the fact.

- The sports media: Another big Olympics story in US media was the performance of Mikaela Shiffrin, a US skiing star who surprisingly failed to win a medal. Shadia Nasralla writes, for Reuters, that Shiffrin ended the Games by delivering a “love letter” to the media, praising reporters for giving her a platform to “celebrate the good” in failure. “There’s a lot of talk about this sort of battle between athletes and pressure and that the media falls on the pressure side of things,” Shiffrin said. “It doesn’t have to be that big of a battle because I’ve had so much support from you guys, from the media as well.”

- Meanwhile, in Ukraine: Through the weekend, tensions continued to ratchet up between Russia and Western powers; President Biden warned that he believes Putin has already decided to invade Ukraine, though he also accepted the principle of a summit meeting with Putin, contingent on him not invading. Over the weekend, a press tour to examine shelling targets in eastern Ukraine itself came under mortar fire, with reporters present having to duck for cover. It’s not clear if the Russia-backed separatists who fired the shells knowingly targeted journalists. Times reporters who were present have more.

Other notable stories:

- Intrigue continues to swirl around Jeff Zucker’s and Allison Gollust’s exits from CNN. On Friday, the Times reported that Gollust was forced to resign after an internal probe examined a trove of messages between her and Andrew Cuomo, the ex-governor of New York for whom Gollust once worked, including an agreement that she would pass on questions Cuomo wanted to be asked during a CNN interview. A spokesperson for Gollust described this as an “everyday practice” in TV news, but the Times notes that it’s unusual for a top executive to get involved, especially given her ties to the interviewee.

- For The New Yorker’s online interview issue, Clare Malone sat down with Dean Baquet, the executive editor of the Times. “He seemed both reflective and defiant; one gets a sense of a man, at the twilight of his career, trying to protect his institution—not only the Times but journalism more broadly,” Malone writes. Baquet said that he has tried to convince his journalists that they should cover “edgy and complicated” stories “independently and fairly, and if Twitter doesn’t like it Twitter can jump in the lake.”

- NPR’s David Folkenflik has more on the Post’s decision to create a desk dedicated to coverage of the growing threats to America’s democracy. “It feels new to me, it feels like a shift,” Folkenflik said. “The best analogy I can think of is thinking about the way in which coverage has shifted on climate change over the years… the stakes are enormous and something fundamental to all Americans, regardless of their beliefs.”

- CJR’s Lauren Harris has more on the Marshall Project’s new local-news collaboration investigating the judicial system in Cleveland. The initiative has “attempted to reimagine distribution to meet audiences where they are,” Harris writes, “partnering with local newsrooms, from newspapers to local Black-owned radio stations; creating a dynamic project website; and putting together one-page flyers that can be distributed locally.”

- HuffPost’s Dave Jamieson explores a union dispute at the San Francisco Chronicle, where HR reprimanded the chair of the paper’s union for violating company email policy by sending union-related messages to bosses’ work accounts. The dispute, now before the National Labor Relations Board, could help set a worker-friendly precedent around the use of company IT in union activity, after the Trump-era board sided with employers.

- According to Joe Douglass, of Discrepancy Report, the Occupational Safety and Health Administration opened an investigation after staffers saw Tori Yorgey, a TV journalist in West Virginia, get hit by a car while reporting live on air last month. (She was not badly hurt.) It is unclear whether OSHA is investigating the broader practice of solo reporting in local-TV news, which has come under renewed scrutiny since the Yorgey incident.

- A global consortium of forty-eight news organizations—led by Süddeutsche Zeitung and the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project, and including the Times and the Miami Herald in the US—is out with Suisse Secrets, a new investigation based on a leak of thousands of bank accounts from inside Credit Suisse. Notably, no Swiss outlet was able to participate in the project due to the country’s draconian banking-secrecy laws.

- Late last year, officials in Ethiopia detained the journalists Amir Aman Kiyaro, Thomas Engida, and Temerat Negara after imposing a state of emergency in the country amid a civil war. Last week, the state of emergency was lifted and the journalists were expected to be freed, but officials now say that they will formally charge Amir and Thomas under an anti-terrorism law and continue to investigate Temerat. CPJ has more.

- And as a storm battered the UK on Friday, hundreds of thousands of people tuned in to Big Jet TV, a YouTube channel that films aircraft, as it live-streamed planes trying to land in high winds at a London airport—a bigger audience “than usually watch many British rolling news television channels,” The Guardian’s Jim Waterson notes. Jerry Dyer, Big Jet TV’s host, has built “a cult audience online for his unfiltered excitable commentary.”

ICYMI: Inside The Marshall Project’s local reporting collaboration in Cleveland

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.