Sign up for The Media Today, CJR’s daily newsletter.

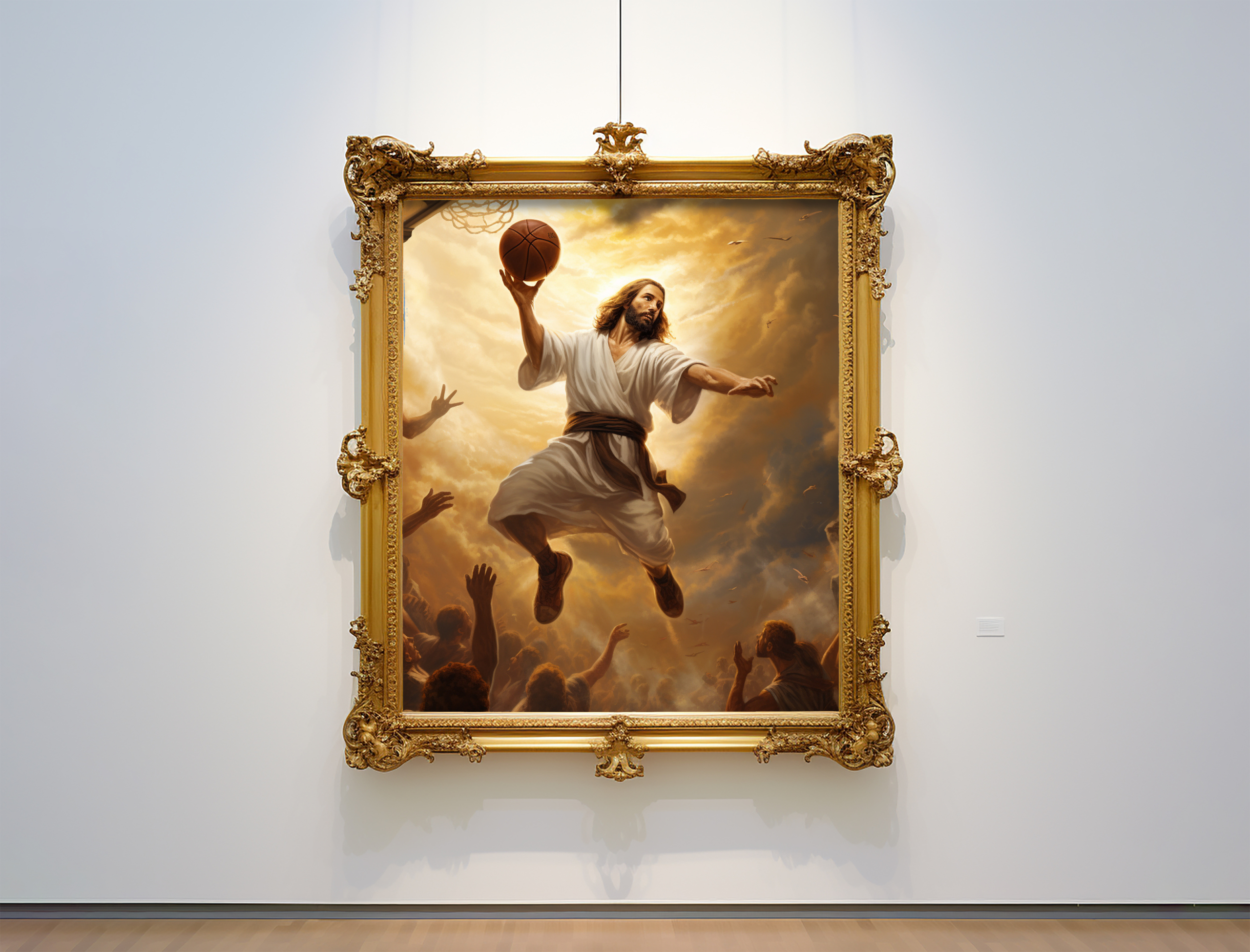

Jesus is in midair, a basketball in his right hand, sneakers on his feet. It looks like a Renaissance painting, except the ball, the net, even the hordes of people looking up at him are at uncanny angles. That’s because this image, composed by Darrel Frost for CJR’s new Business Model Issue, was developed using Midjourney, a tool for generating images with AI. Indeed, all the art for the issue started life as an AI generation, a process that presented both opportunities and challenges. “Producing an image of Jesus dunking a basketball is easy,” Frost writes. “Getting the right image of Jesus dunking a basketball is much harder.”

The technical and ethical questions around the use of AI-generated art in journalism—What are its limitations? Even if there weren’t any limitations, wouldn’t it be wrong to cut humans out of the equation entirely?—are representative of much broader debates that have played out in the media industry, not to mention wider society, as the power of generative AI tools has grown rapidly in recent months. As Hamilton Nolan puts it, also in a piece for the issue, AI has gone from “sci-fi plot point to ubiquitous consumer product in less than a year.” The technology could help journalists with day-to-day tasks—indeed, it is already doing so in many newsrooms—but, as Nolan writes, “its role needs to be carefully negotiated, its deployment guided by an ethical code that has yet to be written.” Nolan, an elected council member of the Writers Guild of America, East, sees a key role for unions in this negotiation: rallying a broad coalition around the shared conviction that “journalism must always be by and for human beings.”

Recently, Frost and Nolan met virtually (how else?) to discuss the potential and peril of AI in the newsroom, how we should talk about the technology, and CJR’s own experiments with it. Their conversation, which was typed over Google Docs, has been edited for length and clarity. —Jon Allsop

DF: “AI” is an umbrella term that covers everything from large language models to image generators to algorithms powering myriad business tools. How should we think about this variety? Are there universal ethical values that we should apply, or do we need a more nuanced approach?

HN: There are definitely universal values governing ethical journalism itself—truth, accuracy, accountability; the things we’re all familiar with—and we’re always responsible for figuring out how any new technology can be used in accordance with those values. The journalism world has had to ask itself these questions with every new invention that changed how we work, from cameras to radio to television to the internet. “AI,” inclusive of all of the things you mentioned, feels like more of a challenge than most technologies of the past, in part because it’s evolving with so much speed—it went from more or less sci-fi to widespread public adoption in the space of a year or two. The media is very much making up standards around this stuff as we go, and it’s still a work in progress. But the speed of change and the broadening capabilities of these AI tools make establishing some actual guidelines very soon even more important. Because if we don’t do it now, all this stuff gets introduced into newsrooms with very little well-thought-out guidance, and it inevitably becomes a race to the bottom. The least scrupulous actors end up defining the boundaries of what should be done.

I think you’re right about the pace—it’s hard to be thoughtful at 186,000 miles per second—but some combination of that speed and our fear leads many conversations to end at “AI is bad,” which is reductive. What are some good uses for AI in journalism that you’ve seen (or that you can imagine)?

I don’t have a crystal ball, but it’s clearly going to be a really powerful tool for doing all types of busywork, like sorting through and summarizing and organizing large amounts of data. It seems to already have reached the level of being able to do the work of a semi-competent research assistant. That’s fine! Streamlining the logistical, busywork, back-end side of reporting seems like a perfectly good use. But I would distinguish that from the front-end, creative, thoughtful side of journalism, which is something that we as journalists should always be able to explain and be accountable for. It seems to me that there is a qualitative ethical difference between using AI as a research assistant, or using it to come up with stuff that serves as some kind of creative inspiration, and using it to actually do creative work like writing or illustration. It’s a tool, and it should always be treated as a tool, not as a replacement for the human mind. Because the “creativity” of AI itself is really just an illusion based on stealing and remixing creative work that humans have already done.

Last week, CJR’s Yona Roberts Golding reported on how media organizations are navigating their relationships with large language models, which train themselves on bodies of text from the internet, and trying to figure out whether and how these organizations should police their copyright as AI companies crawl through their content for this purpose. How do you think journalists should be weighing these intellectual-property questions?

The smart move is for journalists—and authors and artists and media companies more broadly—to try to enforce their copyright claims to the absolute max right now. That is a piece of leverage over the AI companies that is going to disappear if we don’t use it. Right now, the legitimacy of their practice of scraping all this creative output with no permission or compensation still seems like an open question, legally and otherwise. But the more time goes by, the more normalized the AI companies become, the more deeply they become embedded in daily use, and the harder it’s going to be to turn back that clock in any meaningful way. So it is absolutely important to push all of these legal claims now. A victory on this issue could really rewrite the future of AI, at least in terms of who benefits from it.

One of the key questions, as with so much on the internet, is Who controls the tools? And, ultimately, Whom are the tools benefiting? I was struck by a quote in your piece from a media executive who said that it was his “fiduciary responsibility” to use AI, as if he doesn’t have a responsibility to employees or readers.

That is the relevant question. The reason why unions are so critical when it comes to the real-world regulation of AI is that they are the only bodies with the power, right this minute, to ensure that the control and benefit of these tools are not only in the hands of company managers and investors. Responsible news outlets that take things like journalistic ethics very seriously will want to have a thoughtful process to integrate AI into newsrooms—but there are plenty of companies in this industry (hello, G/O Media) where the owners and CEOs will just rush the implementation of AI in whatever way they think will make them the most money the fastest. We’ve already seen that happening in places: bosses have overruled their own newsrooms to publish AI-generated content that has turned out to be embarrassing and full of errors, and have then had to walk it back. There are responsible owners in media, but, as a lot of union members in this industry can tell you, there are also a lot of owners who see journalism as just another business where maximization of profit is everything. If we allow those people to have unfettered control over how AI gets rolled out, it will be a race to the bottom for all of us. Union contracts are the wall against that.

We tried to integrate AI into the CJR newsroom for this issue, actually, at least with the illustrations for each article. We share the values you’ve discussed here, so we used generative-art tools to augment our work, not to replace human creativity. (I wrote about the process here.) In general it was… exciting! It was cool to see editorial ideas literally take shape at the click of a button, allowing us to hone our concepts before hiring artists to develop them. Sure, the machine is just remixing existing human-made art, as you noted earlier, but the upside of that is that using these tools is like brainstorming with a hive mind; it’s like having a hundred assistants as you pull together a mood board. That’s pretty nice!

The downside is that the outputs are ideal as visual concepts and mediocre as actual art. We occasionally had some brilliant images pop out—even a broken AI is right twice a day—and obviously the tools will improve over time, but my main takeaway after using them in the past few months was that, as I wrote in my piece, “to call these systems ‘artificial intelligence’ would be to mislabel them.” They’re just… not that smart? Less like wands and more like chisels (and blunt ones, at that). I guess I’m surprised that anyone would think these tools are ready for prime time, regardless of the ethical questions.

It’s a really interesting experiment, and probably highlights the fact that we all have to be a little humble on AI. Not only is it hard to predict what it will evolve into, but almost none of us can honestly say that we understand the processes it uses to produce what it does now. It’s effectively a magic black box that will grow increasingly sophisticated and refined in spitting out… something. That refinement may just be that these systems become better at deceiving us by giving the appearance of thought; I don’t know. The only guideline that really makes sense to me—whether AI is crude, as you found, or much more sophisticated—is that it’s a tool that needs to stay in our toolbox. It should never take the place of a human mind.

Other notable stories:

- The Committee to Protect Journalists raised the confirmed death toll among media workers resulting from the war between Israel and Hamas to twenty-four after Israeli air strikes killed three journalists in Gaza—Mohammed Ali, Roshdi Sarraj, and Mohammed Imad Labad—since the end of last week. Meanwhile, after the New York Times acknowledged that its initial coverage of a hospital blast in Gaza relied too heavily on unsubstantiated claims by Hamas, Vanity Fair’s Charlotte Klein obtained internal messages showing that several Times staffers expressed concerns about the framing that were not immediately heeded. Le Monde published a similar mea culpa around its hospital coverage. And the editor of an open-source scientific journal was fired after retweeting an Onion article that used satire to draw attention to civilian deaths in Gaza.

- Yesterday, ABC News reported that Mark Meadows, who served as Donald Trump’s final White House chief of staff, was granted immunity to testify to federal prosecutors who have charged Trump over his subversion of the 2020 election. Meadows reportedly told the prosecutors that he repeatedly informed Trump that claims of election theft were baseless—contradicting a book that Meadows himself published claiming that the election was rigged. Also yesterday, Jenna Ellis, a former Trump lawyer, became the latest defendant to take a plea deal in a separate case surrounding Trump’s push to subvert the election in Georgia. Media Matters for America took Fox to task for all but ignoring the news in the hours after it broke, having platformed Ellis back in 2020.

- The Washington Post’s Jeremy Barr profiled Jesse Watters, the Fox host who inherited the prime-time slot left vacant by the ouster of Tucker Carlson earlier this year. Watters “has cultivated a loose, irreverent frat-bro persona—forever dancing on the line of acceptable commentary while occasionally crossing it,” Barr writes—and yet unlike Carlson, who faced repeated advertiser boycotts, his “controversies have typically died down within days, registering more as juvenile than malign.” His rhetoric can nonetheless be extreme: recently, he said on air that he dislikes “how people try to differentiate between the Palestinians and Hamas” since “they all love killing Jews.”

- New York’s Rebecca Traister reviewed a new book by Melissa DeRosa, the former top aide to the disgraced former New York governor Andrew Cuomo. “To note that this memoir lacks self-reflection is like observing that Moby-Dick lacks zebras,” Traister writes. “It is ostensibly an attempt to set the record straight, but it is really an exercise in rehabilitating her image as a glass-ceiling breaker while painting Cuomo in a heroic light.” DeRosa slams Traister in the book; according to Semafor, she threatened New York with legal action for assigning Traister to cover it, but New York published anyway.

- And Britney Spears is out with a memoir, The Woman in Me, that offers lashings of media criticism alongside an unsparing account of her life and the conservatorship that limited her power over it. Spears portrays herself “as battling the media expectation that she remain trapped in girlhood, virginal and helpless,” The Atlantic’s Spencer Kornhaber writes. “But she also writes with mystification about the scale of her story, the extraordinary drama and unfairness of it.” (We wrote about the Britney narrative in 2021.)

ICYMI: Israel wants to shutter Al Jazeera. Will it stop there?

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.