Sign up for The Media Today, CJR’s daily newsletter.

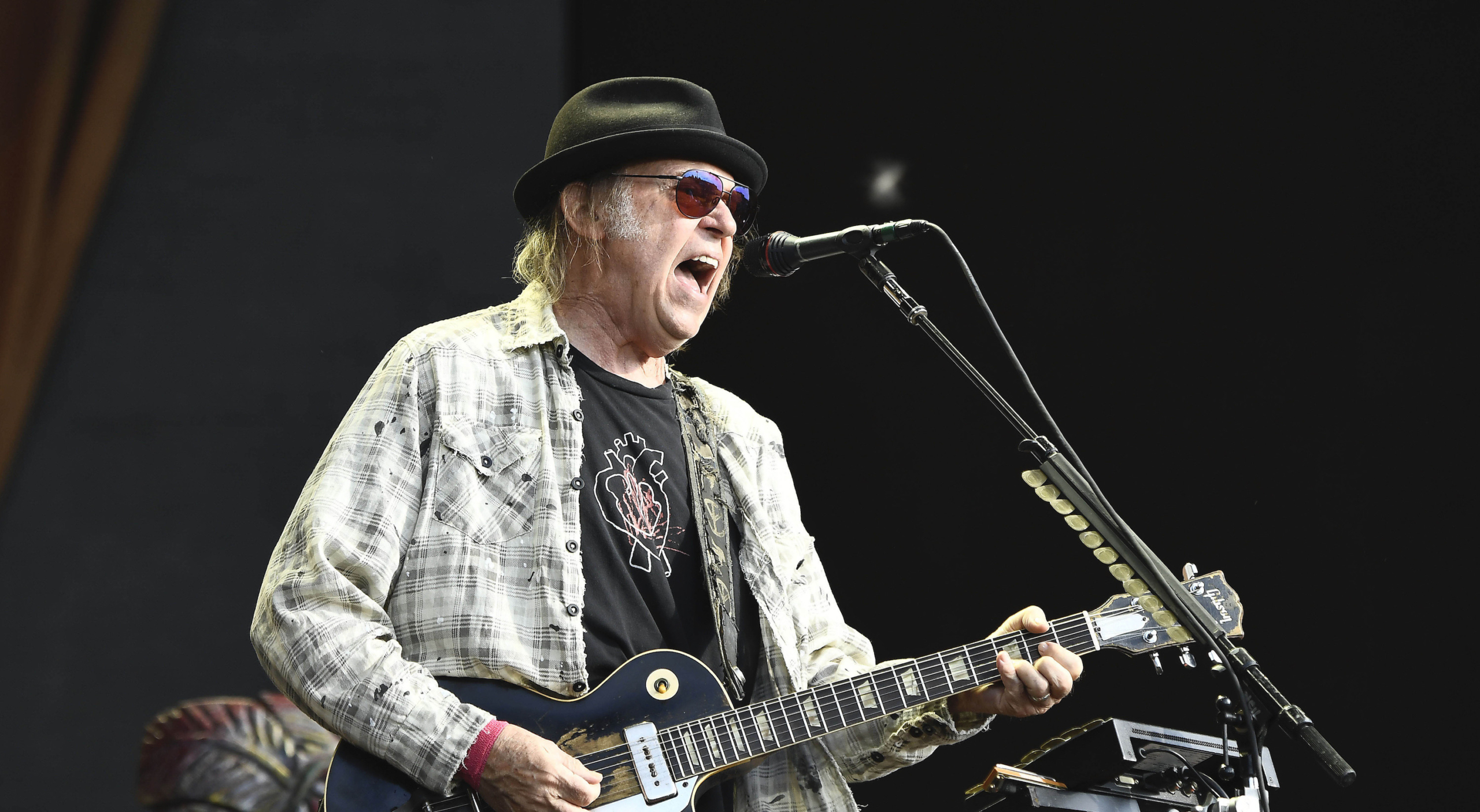

On Friday, Joni Mitchell called a big yellow taxi to pick up her songs and drive them away from Spotify. (Sorry.) She was following the lead of her fellow Canadian musician Neil Young, who demanded earlier last week that Spotify remove his music in protest of its platforming of misinformation about COVID vaccines, specifically via the wildly popular podcast of Joe Rogan, with whom Spotify has an exclusive distribution deal; Young himself was following a recent call from hundreds of science and health professionals objecting to Rogan’s show and demanding that Spotify implement a misinformation policy. (Young published their letter on his website, which is mocked up to look like an old-timey newspaper called the NYA Times-Contrarian.)

Mitchell’s defection answered the question of whether Young would be a one-off, and their call to action continued to generate momentum through the weekend. The rocker and Springsteen collaborator Nils Lofgren, who also performs with Young’s band, Crazy Horse, said that he, too, would sever his ties to Spotify; the alt-rock band Belly said that removing its music from the service would be complicated, but did upload an image to its Spotify homepage instructing listeners to “DELETE SPOTIFY.” Beyond the world of music, Prince Harry and Meghan Markle, who also have an exclusive deal with Spotify, confirmed publicly that they’ve raised private “concerns” about misinformation on the service, claiming that they first did so last April. The professor and author Brené Brown announced that she would not be releasing any new episodes of her Spotify podcasts “until further notice”; she didn’t say why, but reporters covered the news in the context of the Rogan pushback. The British singer James Blunt, meanwhile, jokingly threatened to release new music should Spotify fail to act.

Podcast: Tonga is not for sale

Spotify, not knowing what it had ’til it was gone (sorry again), was forced to respond. Last Wednesday, as it complied with Young’s request, the company said that it had already removed more than twenty thousand podcast episodes “related to COVID” (though this claim arguably raised more questions than it answered). Then, yesterday, Daniel Ek, Spotify’s cofounder and CEO, went into more detail in a blog post, writing that his company has “a critical role to play in supporting creator expression while balancing it with the safety of our users,” and adding that “it is important to me that we don’t take on the position of being content censor while also making sure that there are rules in place and consequences for those who violate them.” Ek said that Spotify has long had such rules in place but admitted that the company had not been transparent about them; in response to the Rogan controversy, he moved to publish them and said that Spotify would soon add “content advisories” to pandemic podcasts, in a (well-worn, for the tech world) bid to steer listeners to accurate COVID information. Ek did not mention Rogan by name, but Rogan, too, responded yesterday. In a video posted to Instagram, he defended his show’s conversational approach, but also apologized to Spotify for causing them trouble, backed the content-advisory suggestion, and pledged to platform a greater mix of views going forward.

Ek’s blog post poured fuel on what was already a lively discussion among tech journalists and experts. Casey Newton, who writes the newsletter Platformer, described Ek’s pledges as “some good first steps,” but said that the company’s platform rules “need a lot of work,” calling similar rules at Facebook “100x more detailed than this.” My CJR colleague Mathew Ingram was more scathing, writing that “content advisories will definitely work for everyone who takes the time to read the list of ingredients on boxes of food, which is to say no one.” A couple of tech reporters noted the obvious similarities between Ek’s post and statements that Facebook has had to issue throughout the pandemic in response to criticism of its platforming of junk information; others stressed the crucial difference that Spotify not only chose to partner with Rogan, but so did during the pandemic. “Spotify is leaning directly into the comparisons to Facebook and YouTube; it lets them run the ‘content moderation is an impossible challenge’ playbook instead of the ‘we bought and distribute this media property’ playbook,” Nilay Patel, the editor of The Verge, wrote. “This is like HBO responding to criticisms about drug use on Euphoria by saying content moderation at scale is a difficult problem.”

All this ties into the longer-term debate (often overshadowed by Facebook discourse) around Spotify’s responsibilities in the area of content moderation. Some of the nuances of this debate are pretty specific—moderating audio is hard; Spotify also hosts music, which does not have the same needs as news—but it mostly boils down to a more fundamental conceptual question: is Spotify a platform or a publisher? Spotify has insisted the former, and the latest Rogan controversy has inevitably met with cries of censorship and “cancel culture” in right-wing, right-curious, and some left-wing circles. (Elie Mystal said that he is less worried about Spotify platforming “ignorant dumbasses” than the New York Times legitimizing them “in their thirst for both sides coverage.” He could have said Both Sides Now; really, this will be my last one.) Various critics strongly disagree. Calling Spotify an “obvious media company,” Kara Swisher, of the Times, blasted Ek’s warning about censorship as an example of “wordwashing by tech folks who want all the power and money and none of the responsibilities when things get dicey, as things always get.”

Whichever it is—and I incline toward the Swisher view—Spotify could be a lot clearer about how it draws lines around content, and say publicly whether Rogan has crossed them. (The Verge’s Ashley Carman reported last week that an internal review of controversial Rogan episodes concluded that none met “the threshold for removal”; Carman also obtained and published Spotify’s rules around health content before the company did so itself.) In many ways, this controversy is just the latest iteration of a longstanding debate about misinformation and free speech online that COVID has rendered especially relevant and especially difficult; my colleague Ingram wrote just last week about the thorniness of policing facts in a context of widespread scientific uncertainty. In other ways, however, this episode seems more immediately to concern two ideas that, while related to misinformation, are ultimately distinct concepts.

The first is attention; it should go without saying that we’re having this debate about Rogan because of the enormous reach of his output. Attention has often been central to COVID-era complaints about the algorithmic boosting of viral garbage on Facebook and other platforms, but the context here is somewhat different. As Carman wrote last week, while the podcasting industry may hope that “software recommendations will do more some day in the future,” it is “not there yet… meaning Spotify not only sided with its star podcaster but is also completely financially motivated to push his content to users and can’t even blame a bad algorithm.” At the same time, as Carman reported last year, Rogan’s exclusivity with Spotify appears to have limited the reach he enjoyed when he was more of a multi-platform operation. In other words, Rogan is huge on Spotify with Spotify’s help, but he doesn’t need Spotify to capture people’s attention. He was doing that fine on his own, and would doubtless do so again should Spotify kick him off.

Which brings us to a second idea: association. The possibility that Spotify might implement tougher content policies transcends Rogan’s podcast, but much of the furor here seems, as is often the case in the culture wars, about the side that Spotify is choosing to be on. Young, Mitchell, et al might want Spotify to deplatform Rogan, but they aren’t censoring him—ultimately, only Spotify has the power to do that, and it has a clear financial incentive not to do so—as much as using their fame to make a moral argument about the people and values with which they choose to share space. Young said as much on Friday, arguing that he has “never been in favor of censorship,” and that “private companies have the right to choose what they profit from, just as I can choose not to have my music support a platform that disseminates harmful information.” (Despite conservative howling, this is, in fact, how the free market works. Apple Music and other services are already vying to call themselves Young’s natural “home.”)

There are speech implications to this debate, but it ultimately boils down—as these things so often do—to age-old tensions between competing freedoms, and journalists would always do well to remember these when covering cancellation. On The Verge’s podcast last week, Newton channeled this idea after Patel predicted that Rogan might just quit Spotify and take a massive sponsorship deal to go independent again. “I think that might be a good outcome,” Newton said. “If people wanna listen to Joe Rogan, listen to Joe Rogan. I come at this from the perspective of a paying Spotify customer and somebody who worries about what the largest platforms promote to audiences of hundreds of millions of people… But if Joe wants to go run his RSS feed from his ranch in Texas and take gambling money to do it, I have no issue with that.”

Below, more on Rogan, Young, and content moderation:

- Dept. of paving paradise (OK, I lied): It’s not just COVID misinformation: last week, Rogan discussed the climate crisis with Jordan Peterson on an episode of his podcast that also drew the ire of the scientific community, particularly around Peterson’s contention that long-term climate modeling is too erratic to be relied upon. “He seems to think we model the future climate the same way we do the weather,” Sarah Perkins-Kirkpatrick, of the University of New South Wales Canberra, told The Guardian. “He sounds intelligent, but he’s completely wrong. He has no frickin’ idea.”

- Rockin’ in the free world: Writing for Pitchfork, Sam Sodomsky points out that this isn’t the first time Young has taken a stand against a distributor of his music. “Young doesn’t need Spotify—in the same way he didn’t need MP3s (‘Download this/Sounds like shit,’ went a line from 2009’s ‘Fork in the Road’), iPods (Pono anybody?), or even CDs,” Sodomsky writes. Now Young is “escalating his grievances—to his mainstream audience, he is now framing Spotify as not just the latest extension of a morally bankrupt music industry, but also as a willing vessel for harmful misinformation.”

- Substack: As Clio Chang explored in a recent edition of CJR, the newsletter company Substack has also found itself at the heart of the “platform or publisher” debate. Last week, after the Washington Post’s Elizabeth Dwoskin reported on estimates that Substack makes million of dollars from anti-vax content, its cofounders published a blog post describing the platforming of writers with whom they disagree as “a necessary precondition for creating more trust in the information ecosystem as a whole,” adding that the more “powerful institutions attempt to control what can and cannot be said in public,” the more “people there will be who are ready to create alternative narratives.”

- Twitter: On Friday, Twitter confirmed to CNN’s Daniel Dale that it stopped taking aggressive action last March to curb the spread of 2020 election lies on the platform. Twitter is no longer enforcing a civic-integrity policy “under which the company had suspended or even banned users for lying about the 2020 election, affixed fact-check warning labels to tweets containing such lies and limited others’ ability to share those inaccurate tweets,” Dale reports. A spokesperson told Dale that the policy still exists but “is ‘no longer’ being applied to lies about the 2020 election in particular.”

Other notable stories:

- Politico explored why President Biden and his officials have largely avoided engaging with progressive media, a position that bewilders many operatives and stands in stark contrast to Trump’s incessant outreach to his base. “Republicans are scared of their base and Democrats hate their base,” Ari Rabin-Havt said. A progressive-media executive added that Democratic donors fail “to grasp how information moves today.”

- In media-jobs news, Tara Palmeri is reportedly stepping down as co-author of Politico’s DC Playbook newsletter; she’ll stay at Politico as chief national correspondent and will also anchor a new Sunday product. Elsewhere, Gayle King confirmed reports that she’s decided to sign a new contract at CBS. And Stephen Hayes, who made a splash when he quit Fox last year in protest of its programming, is now a contributor at NBC.

- The Guardian’s Sam Levin spoke with Rahsaan Thomas, an incarcerated journalist in California whose sentence was recently commuted by Gavin Newsom, the state’s governor. It could still be years before Thomas walks free (he has to go before a parole board), but “the uncertainty is not stopping Thomas from mapping out ambitious plans for life after incarceration”; the “big thing” he wants to do, he says, is write books.

- Debra Tice—the mother of Austin Tice, an American journalist who was kidnapped in Syria in 2012—called on Biden to raise her son’s case with the emir of Qatar, who is visiting the White House today; Qatar opposes Syria’s Assad regime, but has often served as a broker in international hostage negotiations, including the talks that freed Bowe Bergdahl, a US soldier, from Taliban captivity in 2014. Zachary Basu has more for Axios.

- Ronen Bergman and Mark Mazzetti, of the Times, took a deep dive into Pegasus, the potent spyware tool, reporting that the FBI bought a version of the software but finally decided not to use it. Among other ends, repressive leaders have used Pegasus to surveil reporters; last week, four Hungarian journalists said that they would seek legal redress from their country’s government and the Israeli firm that created Pegasus.

- HuffPost’s Christopher Mathias spoke with Emily Tamkin, a biographer of George Soros (and former CJR contributor), about the “perfect anti-Semitism” of a new Tucker Carlson documentary focused on Soros’s supposed “demographic war” on the West in general and Hungary in particular. “They’re building up and fighting with Soros the myth,” Tamkin said. “It’s proven politically useful so far and so they are going to continue to do it.”

- In the UK, the BBC paid out more than two-million dollars to settle the cases of eleven former production staffers who died of a form of cancer caused by exposure to asbestos. The broadcaster said that it was “not possible to confirm” how the eleven individuals were exposed, but has previously warned staffers in various studios that they may have come into contact with asbestos. The Observer’s Denis Campbell has more details.

- In a column for the New Zealand Herald, Charlotte Bellis, an unmarried Kiwi journalist based in Afghanistan, writes that she had to turn to Taliban officials for reassurances about her pregnancy after authorities in New Zealand denied her application to return to her home country, access to which is still limited due to strict COVID-quarantine rules. Her application is now under review, but she describes her situation as “messed up.”

- And on CJR’s podcast, The Kicker, Kyle Pope, our editor and publisher, spoke with Damien Cave, the Sydney bureau chief at the Times, about the challenges of covering the crisis in Tonga, where a massive volcanic eruption unleashed a tsunami and cut off the country’s internet. “The scientific information came out pretty quickly,” Cave said, but “the voices of the people on the ground, who were affected, were completely silenced.”

ICYMI: Britain get its own, much sillier Mueller report

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.