Sign up for The Media Today, CJR’s daily newsletter.

Fifty-five years ago last month, Robert F. Kennedy—the brother of JFK and surging candidate for the 1968 Democratic presidential nomination, who had just won the California primary—was making his way to a press conference when he was shot dead. Kennedy had been talking to a reporter when the shot was fired; a staffer from ABC News was hit, too, but survived. As Stephen Battaglio, a media reporter at the LA Times, wrote on the fiftieth anniversary of the assassination, it saturated TV in the days that followed, presaging, in a sense, “how America would absorb traumatic events in years to come on 24-hour cable news and then social media.” On air, journalists opined about the assassination and speculated darkly on what it portended for the country—modes of TV coverage, Battaglio noted, that are common now but were rare at the time, as the networks privileged a dispassionate tone. Chris Wallace, now a CNN anchor, watched his father, Mike, cover the killing for CBS. “That was the moment when I began to wonder if the country was coming apart,” Chris Wallace recalled. He was far from alone.

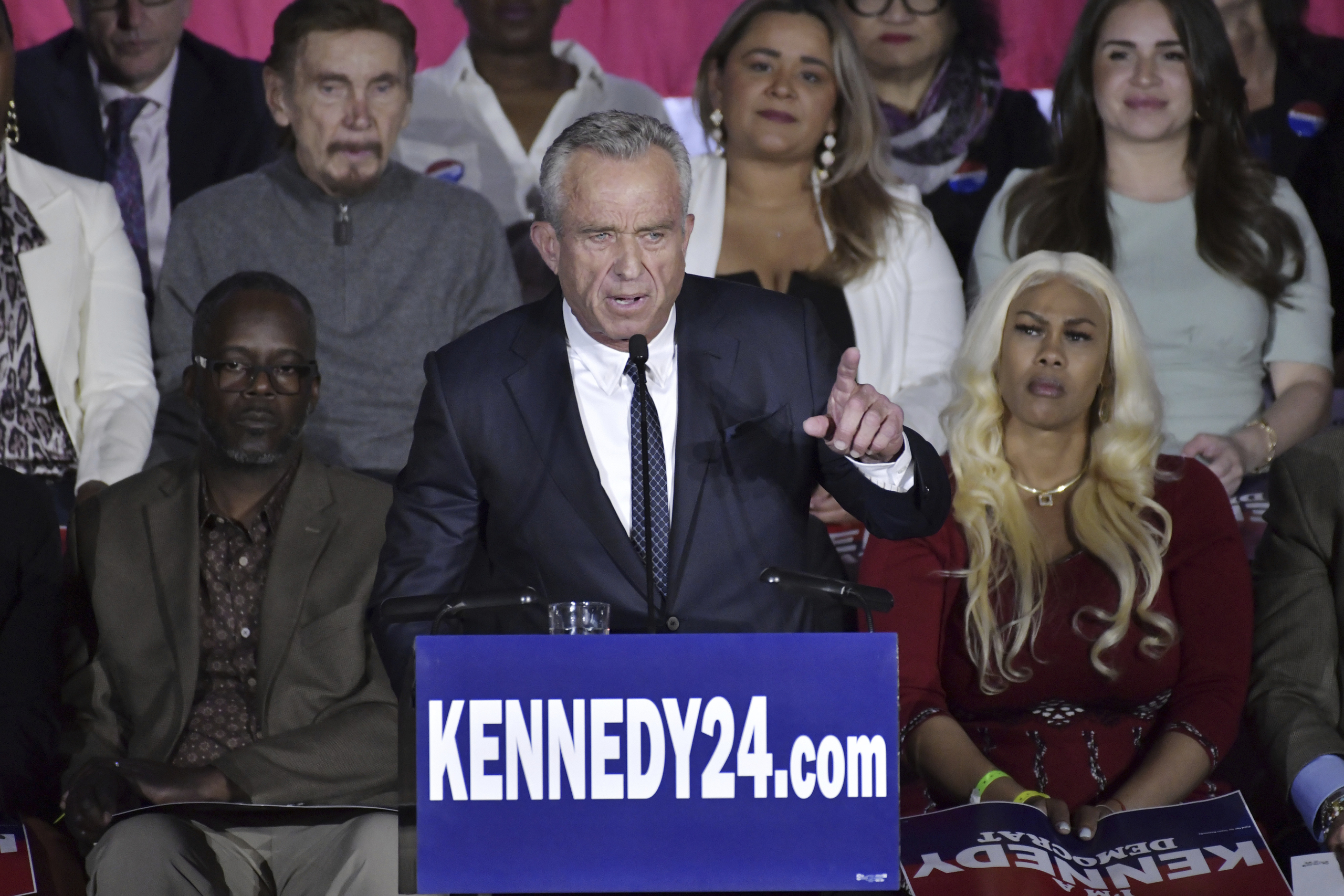

Last month, a smattering of major news organizations reflected on the fifty-fifth anniversary of the assassination and Kennedy’s legacy (in NPR’s words) as a “liberal icon.” Around the same time, however, it was his son Robert F. Kennedy Jr. who was garnering the greater media attention as he embarked on a Democratic presidential primary campaign of his own. The younger Kennedy is not a liberal icon—he is a conspiracy theorist, most notably on vaccines, whose views range from the esoteric to the dangerous. Despite—or, much more likely, because of—this, Kennedy has recently sparked chatter everywhere from bullet-point items in political tipsheets to long-form profiles in hallowed magazines, which have typically emphasized both his kookiness and his Kennedyness. He has also made the rounds of right-wing or right-wing-curious podcasts. (If TV framed his father’s 1968 bid, Kennedy has said that the 2024 election will be “decided by podcasts.”) He suggested to Joe Rogan that the CIA was involved in the assassination of JFK, his uncle, and said that he’s “aware” that he could meet the same end.

Kennedy’s campaign is far from his first brush with the press; he’s danced with it, in some capacity, almost his entire life, as contributor, subject, and antagonist. According to Rebecca Traister, who wrote one of the aforementioned Kennedy profiles for New York magazine, major mainstream outlets, many of whose staffers were personally friendly with Kennedy, published his writings as far back as the 1970s; when Traister asked him how he is getting ready for the presidency, he cited essays that he has written for The Atlantic and (much more recently) Politico as evidence of a “lifetime” of preparation. In 1980, Kennedy tweaked the press as he worked on his uncle Ted’s presidential campaign (“If we get a little fair treatment from the press, we’re going to win,” he said). In the nineties, New York put Kennedy on the cover with the caption: “a New York political player with a future.” Then, in 2005, Rolling Stone and Salon jointly ran a long piece by Kennedy about vaccines and autism that garnered significant media buzz but was later debunked and retracted—moves that Kennedy has pinned, baselessly, on media complicity with Big Pharma. As NBC’s Brandy Zadrozny put it, sometime after that, he “disappeared from most networks and news organizations,” a virtual pariah.

Until his current media moment, at least. Kennedy’s press person told Zadrozny that so many journalists had been assigned to cover his campaign that it wouldn’t be possible for her to join him at an official event. (They went hiking together instead.) When coverage of a conspiracy theorist ramps up, discussions about how to responsibly cover them are rarely far behind, and this time was no exception. (Zadrozny herself guest-hosted an insightful On the Media episode that tackled the question.) Media critics chided various outlets—ABC, CNN, NewsNation—for falling short, for reasons that ranged from refusing to air Kennedy’s vaccine lies to failing to adequately push back on them. (Also: for devoting airtime to a topless workout video that he posted, and his “body even Rocky would admire.”) Soon, a familiar debate had taken shape, between those claiming that Kennedy can’t be ignored, and those urging us all to do just that.

As I wrote in May after CNN’s decision to give Donald Trump a live town hall sparked a previous iteration of this debate—to platform a known liar or not—this is, in many ways, a false choice: how one platforms a candidate matters (CNN made some bad editorial choices that blunted its ability to challenge Trump’s claims), and it is not “censorship” for one outlet to deny one politician a certain type of platform, in particular. In some respects, Kennedy’s candidacy requires us to think along similar lines. But it also poses a different challenge for the press. Trump, at least these days, is an unavoidably massive media object, one that often blacks out the sun; RFK—while famous and in many ways a known quantity—has, by contrast, only recently conjured himself back into mainstream political relevance by declaring for president. Confoundingly for the press, the answers to the questions Isn’t it dangerous to indulge Kennedy’s efforts to mainstream himself? and Isn’t it dangerous to dismiss his views as irrelevant? might both be “yes.” And both potential paths, it seems to me, constitute a different form of complicity, making the question of which one we should take very complicated indeed.

As I see it, there are a few cases for paying attention to Kennedy’s candidacy, in addition to the imperative of calling out his noxious views. One is simply that he is running for president; another—cited explicitly as a reason for covering Kennedy by at least one major outlet—is his polling, which has reached as high as 20 percent support within the Democratic field. He is, in many ways, a ready-made media character. More than just that, he has been presented as an avatar of conspiratorial trends—and attendant anxieties about them—that have become central to American intellectual life, making him, also, a representative of the zeitgeist. (The fact that he is a scion of perhaps the most zeitgeisty political family of all time hasn’t hurt this impression.)

Some of these arguments have more merit than others. As I wrote recently, the idea that a rich and famous person can essentially buy themselves media attention by pouring money into a quixotic presidential bid is troubling for a range of reasons, as is the idea of leaning on polling as the key metric of how we distribute that attention. (Kennedy’s high numbers, in particular, strike me as soft; as a friend recently put it to me, a trash can with a smiley face drawn on it could get 20 percent in early Democratic primary polls if it was also named Kennedy.) Equally, though, if Kennedy’s campaign were to catch fire, and the press were to have ignored it to that point, we would—rightly—be accused of having dropped the ball. Even if his polling bottoms out, Kennedy could, with relatively scant support, still end up running as a third-party candidate and play spoiler in key states in a close election. Nor, importantly, is Kennedy reliant on the mainstream press for oxygen; there’s always a podcast for that. If his views are out there anyway, and have a significant audience, isn’t it best for us to loudly and clearly debunk them?

Some sharp articles, including Traister’s and Zadrozny’s, have already interrogated Kennedy’s policies and the sort of damage he’d be liable to do as president, not least to the vaccine approval process. And yet, at the same time, even good coverage risks introducing Kennedy’s ideas to those who might not otherwise have heard about them, and of actively inflating his political relevance; a glut of glossy magazine profiles, even if they’re all insightful on their own terms, can collectively elevate a candidate to discourse centrality. I find it hard to escape the conclusion that while no Kennedy coverage would be too little, the current level of coverage is way too much. To some extent, this is a media collective-action problem that is hard to avoid. There is (thankfully) no centralized bureau of magazine profile assignments.

In its absence, I would perhaps encourage individual reporters and editors to think particularly hard on three big-picture questions before committing to further coverage: Is Kennedy really a zeitgeist figure? If so, what is the nature of that zeitgeist? And is Kennedy really central to it? The answers, as I see them, muddy the premises for his relevance. There is no doubt that the appeal of conspiracy theories is a huge problem in current American life, but it can be easy to overstate their grip on the body politic. (Responding to what he described as the “doomed RFK Jr. hype cycle” recently, for example, David Wallace-Wells, of the New York Times, pointed to data showing that “mRNA Covid vaccines are actually hugely popular.”) As The Atlantic’s Yair Rosenberg wrote in a compelling essay last week, to the extent that Kennedy seems genuinely popular, it’s likely a function not of his policies but of generalized antiestablishment sentiment. Even if Rosenberg is wrong, lavishing attention on Kennedy is arguably missing the disease for the symptom. If he is right, then Kennedy comes to seem even less central. The story of antiestablishment sentiment dates back not only to his dad’s day, but much further still. There have been plenty of moments at which the country appeared to be coming apart.

Ultimately, however much coverage you think Kennedy is worth, attention is clearly a currency to people like him. He has been fairly explicit that he entered the race to get more airtime—“There are rules that make it difficult for the public airwaves to censor you,” he told Zadrozny, citing a federal law not quite correctly—and even if greater exposure to his views doesn’t help him politically, it does enhance him as a political character. At the very least, we need to be self-aware about that—and our role in an ecosystem in which name recognition begets media attention begets more name recognition begets more media attention, and so on.

Where Kennedy came from is central to this, of course. As Traister wrote in her profile for New York, “He gets traction where no one else would. His relationship with the political media, which has published him, written about him, and seen him as a full and flawed and interesting human, has always been guided by his core identity as an insider, a member of the family that this country was taught to love above all others and to pity in their many public tragedies.”

Other notable stories:

- Yesterday, more than two dozen writers and editors in the sports department at the Times wrote to management to demand answers about the future of the section, which, the staffers wrote, has been left “twisting in the wind” ever since the paper acquired the sports site The Athletic last year. The Washington Post has more (and the Wall Street Journal discussed the Athletic acquisition with David Perpich, a top Times executive).

- As part of a series of essays on the legacy of the pandemic, Wallace-Wells, of the Times, interviewed Rochelle Walensky, the outgoing director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “I think misinformation and disinformation, people working to undermine the messaging—that was a problem,” she said. “Throughout the pandemic, I think there has been an undermining of trust in science and trust in medicine.”

- In the UK, the tabloid The Sun reported allegations that a top anchor at the BBC paid tens of thousands of dollars to a young person for explicit images starting when the person was seventeen—a possible breach of British laws around the sexual abuse of children. The anchor has since been suspended by the BBC pending an investigation, but he has not so far been named publicly, likely due to restrictive British media laws.

- In other BBC news, the government of Syria canceled the accreditation of two of the broadcaster’s journalists inside the country, blaming “false” and “politicized” coverage. In other press-freedom news, the journalist Luis Martín Sánchez Iñiguez was found murdered in Mexico. And the Committee to Protect Journalists condemned officials in Belarus after the journalist Andrey Famin was sentenced to seven years in prison there.

- And Semafor’s Ben Smith reports that independent Russian journalists are largely staying put in Latvia, which has become a hub for exiled media since Russia invaded Ukraine, despite the “complexities” of working there. Smith had expected to find “an exodus” of Russian journalists after Latvian officials stripped an independent Russian TV network of its license last year. (ICYMI, Annie Hylton wrote about the network for CJR.)

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.