Sign up for the daily CJR newsletter.

As 2024 dawns, we’re bringing you a new newsletter every Friday: “The Scrum,” a weekly column on the intersection of media and politics, written by Cameron Joseph, who has covered elections and the seat of power for outlets including VICE News, the New York Daily News, and The Hill. The rest of our newsletter schedule will remain unchanged. Read on for Cameron’s first dispatch. —Jon Allsop

Welcome to the first edition of The Scrum. This is not going to be an insidery industry column. I don’t have the sources, and frankly I don’t care that much. I’m also not some media heavyweight with experience running newsrooms and keen insight into the boardrooms of news companies, or a professor with vast classroom experience.

What I do bring is a lot of firsthand experience of what it’s like to actually cover modern politics. I’ve spent fifteen years reporting on the chaotic, unpredictable, and alarming struggle for democracy—while trying to fight the herd mentality that develops when traveling in packs of reporters. I’ve covered campaigns, Congress, and the White House; worked for strictly nonpartisan outlets (National Journal) and liberal ones (Talking Points Memo); and written for a Beltway-insider newspaper (The Hill), a punchy New York tabloid (the Daily News), and the digital side of a hipster TV operation (Vice News). Throughout my career, I’ve tried as best I could to avoid easy narratives (especially ones that confirm my own biases or fall in my blind spots) and to cover people fairly and with compassion—while pulling no punches.

That’s what I’ve aimed for, anyway.

With this column, I plan to explore the tensions, problems, and clashes facing modern political journalism in a time of massive upheaval—both within the industry and in our broader politics. And I’ll examine the efficacy of the rules and ethics that many reporters were taught growing up, at a time when those very rules are being challenged both by traditional business pressures and the criticisms of a younger generation.

It’s going to be a long, wild, and likely bleak year in American politics. We reporters are stuck right in the middle, trying to figure out, in real time, what the hell is really going on—and find ways to explain it to our audiences in the fairest, clearest ways possible. I’m not going to pretend I have all the answers. I’ll be here to try to make sense of it all—for you, and for myself—as election season officially kicks off in Iowa next week. I hope you hold me accountable.

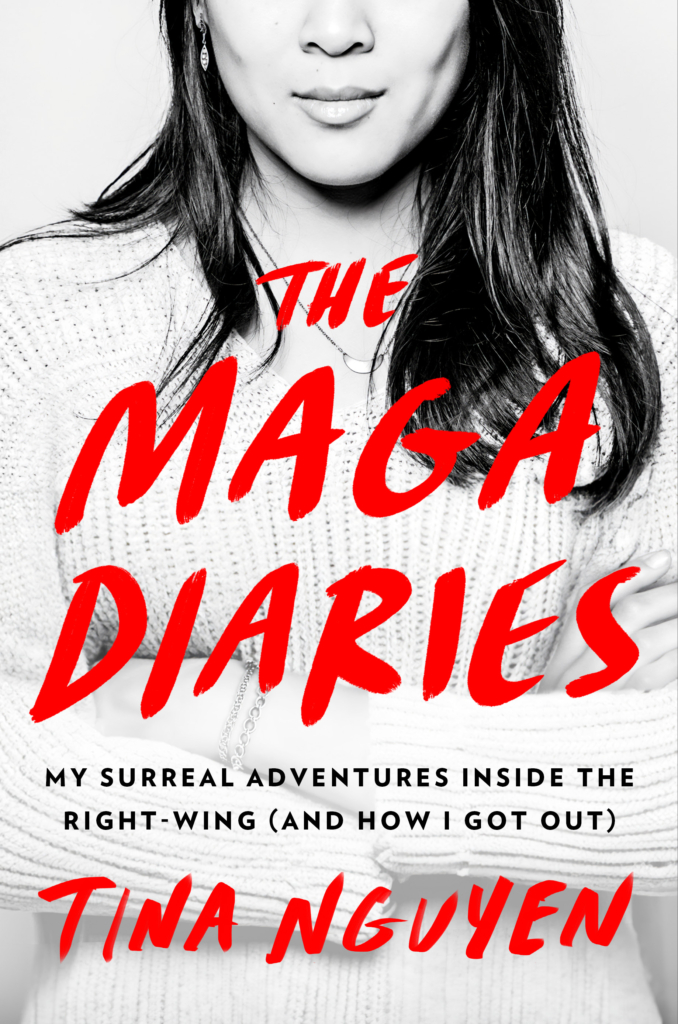

To kick things off, I talked to Tina Nguyen. She’s a national correspondent for Puck and an alumna of Politico and Vanity Fair—and, before that, a slew of right-wing publications where she got her start in journalism. (She’s also my friend.) Her new book, The MAGA Diaries, chronicles her coming of age within the right-wing movement and the conservative media-industrial complex. Her time inside the movement gives her a unique perspective on the forces behind MAGA—and intimate knowledge of many of the people now running the show. Our conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

CJ: We both happen to have gone to Claremont McKenna College, this little school in California that has been a breeding ground for conservatives. How did you wind up at Claremont?

TN: Frankly, I followed a boy there—which is never quite the best reason to go to a college. But I also was a Founding Fathers geek growing up in high school. And the moment that you see a research institution on campus that promises to study the ideals of individual freedom in the modern world, and then you run into another institute that talks about preserving the American founding, and you realize, “Oh my God, I could study this for a living and there are people who do this for a living”—that’s pretty cool.

Readers might know the “boy” you mentioned: Charles Johnson, who later emerged as one of the more notorious figures of the alt-right. In your book, you also write about one of your mentors, who helped to get you some of your first jobs in DC—and later turned out to be palling around with white nationalists. And one of your first bosses, Tucker Carlson, turned out to be…well, the Tucker Carlson we know today. What was it like to see all of these figures from your early time in politics become the people they’re known as today?

Every single time I read something that one of those guys had done at some point, my first reaction was always, “What the hell? Oh my God, why?”’ And then you think about it, and you’re like, “Oh, this makes sense.” And it all boils down to incentive.

I think that in the case of Charles and my mentor, John Elliott, these were views that they’d always held, but then found mechanisms and avenues within the conservative movement to make them mainstream, either through being a wild and crazy troll on the internet who had the patronage of people like Peter Thiel, or by working undercover using these mentorship networks to identify potential white nationalists and workshop ideas with them on how to publish white nationalist stuff in places like the Daily Caller, which in no universe would have ever explicitly courted white nationalists when I was there. And they wouldn’t have gotten there if these networks of support hadn’t existed to make them influential.

In the case of Tucker—this is going to be a hot take, but I think the qualities that made him a really good magazine reporter do not make him a good pundit. He was always really interested in exploring the most crazy, bizarre little corners of American life. Tucker Carlson from back then one hundred percent would be talking to conspiracy theorists and eugenicists just to, like, understand what it is that made them tick. But in the medium of print, that comes across as way different than doing it on Fox News.

And [on top] of that was the very different level of scrutiny he received as a pundit who suddenly had all of these progressive groups and other journalists who were formerly in his community going, “Oh my God, how dare you say these on television?” I think it sort of drove him into being more MAGA. He was reacting to whatever hate and anger came his way.

And I know that kind of sounds a little hand-wavy and excuse-y to the CJR readership. But I’ve seen this happen with so many other people in the conservative movement that it is not me trying to do Tucker Carlson a solid. It is an actual honest-to-goodness trend and hallmark of the movement.

So you think that Tucker Carlson’s move politically, from this kind of mainstream-y, puckish libertarian to this fire-breathing nationalist, is authentic?

Absolutely. Tucker Carlson is definitely the kind of guy who would rather be in a basement livestreaming from a shitty iPhone than having an executive at Fox News telling him what to do. And that’s something that’s been consistent throughout his entire career.

I remember going into reporting on what Tucker was going to be doing after he got fired from Fox. And everyone I spoke to from the mainstream side was like, “He’s probably just gonna, like, take this position of defiance in order to negotiate a better exit package from Fox.” And I am going, “Absolutely not.” He will sacrifice $40 million in order to break that noncompete that told him to be silent for two years past the end of the 2024 election. Like, that is something Tucker absolutely would refuse to do. And you know what? That’s what happened.

At one point in the book, you describe your life as “a very weird gray zone,” as a reporter who covers the movement you came up in. Can you unpack why that’s such a weird place to be?

It all boils down to loyalty, I think—and gratitude. There’s no way I’d be in the place I am right now if not for being part of the libertarian/conservative journalistic community, which gave me this insight into other aspects of conservatism that a lot of mainstream reporters just don’t have.

Internally, I keep having this sense of “Oh my God, I’m betraying my college friend group and the people who mentored me and the people who did me all of these big solids in the past.” If it weren’t for these networks, I wouldn’t have gotten the job at the Daily Caller. Even [though] I got fired from the Daily Caller, if it hadn’t been for Tucker being, like, a really nice person who gave me a recommendation for my next job, I wouldn’t have ended up in New York, writing for Vanity Fair.

I don’t think anyone who came up outside of that movement quite understands that internal tension. And honestly, if I’m feeling like this as someone who’s simply writing about the movement, I cannot imagine what it is like to be someone inside that movement who is unhappy with the way things are going but either can’t get out or feels like if they leave, they’re junking twenty, thirty years of their entire lives.

The ethics of covering folks who you used to be friends with and work with is really interesting. How do you approach that, especially with folks who you didn’t know previously who are now sources or subjects of your stories?

It’s been an interesting process.

I think what helps get over that hump is the fact that my exit from the movement proper [in 2013] was way before any of this Trump stuff came into play and any of the ex-Republican-industrial complex sprang up.

I can go into reporting on this movement as someone who is like, “Okay, no, I don’t believe the things that you do, but I understand you and your world and your ideology much better…than a historian or someone on the outside [would].”

I have a problem with telling people things that I see, and they just try to convince me that the people I’m reporting on are wrong. I’m like, “Are you kidding me? I am simply telling you what’s happening. Why are you attacking me?” I’m not an advocate for the people I report on. I’m just someone who understands what it is they live in and what they talk about.

What are some trends you’re seeing now on the right that you think aren’t really being grasped by other so-called mainstream reporters?

This election [for many on the right] is not about election denialism. It is really about the fight against wokeism. I guess you could define that as efforts from elite institutions to create more equity—in civic education, civic life, academia, corporate America—at the expense of what Americans think is their ability and merit to get ahead. And one of the things I’ve been running into that is met with either bafflement, verging on disdain, from mainstream reporters and progressives especially is the idea that there are more minorities supporting Trump this round than there were last time.

For folks who are not coming from this world, but are trying to cover this in a smart and real way, what do you advise them to do?

Read! Read, read, read, read, read. There are so many conservative blogs out there, so many conservative commentators. There are books about the conservative movement, but then there are people within the conservative movement who will just be, like, laying out reams and reams and reams of exactly what it is they believe. Go into reading all of this not with the “Oh my God, how can they believe this?” but with a “Hmm, why do they believe this?”

Other notable stories:

- As we noted previously in this newsletter, last weekend, Hamza al-Dahdouh and Mustafa Thuraya, two journalists in Gaza, were killed in an Israeli air strike on a car in which they were traveling; Israeli officials initially said that the journalists had been traveling with a “terrorist” who had been operating a threatening aircraft, but later suggested to NBC that the journalists had been flying a drone which made them look like terrorists, and that their deaths were “unfortunate.” On Wednesday, however, Israeli officials claimed that al-Dahdouh and Thuraya were themselves members of “Gaza-based terrorist organizations.” The officials released what they claimed was documentary evidence, but experts consulted by the BBC sounded skeptical of its authenticity, while relatives of the journalists dismissed Israel’s claims as “fabricated.”

- Yesterday, NBC moved to implement layoffs in its news division; a source told Deadline that between fifty and a hundred staffers would be affected, but that they would be encouraged to apply for open positions for which the network is still hiring. In other media-labor news, KCRW, a public-radio station in Santa Monica, is buying out more than a dozen staffers, including several prominent broadcasters, and ending its daily news program Greater LA; the LA Times has more. And the Austin Chronicle reports that staffers at the local American-Statesman, a newspaper owned by Gannett, are preparing to go on strike, citing stalled negotiations with management since the newsroom moved to unionize in 2021. (The union held a one-day walkout last summer.)

- In happier industry news, Slate announced that it has acquired Death, Sex & Money, a popular podcast that was a notable victim of broader cuts at its previous distributor, WNYC, last year. Anna Sale will stay on as the show’s host. Sale said that she was “thrilled to be joining Slate to make new Death, Sex & Money episodes,” and that she was attracted by the site’s “long track record of growing and taking care of listeners,” calling it “a wonderful new home to both pick up where we left off and try new things to meet this moment.” LaFontaine Oliver, the president of New York Public Radio, said that WNYC was “glad we were able to secure a new home for the show at Slate.”

- A trio of updates on stories we noted earlier this week: the tech newsletter Platformer announced that it is quitting Substack over the platform’s failure to commit to banning pro-Nazi content. The board of the Houston Landing—a buzzy nonprofit news site whose CEO, Peter Bhatia, recently fired the popular editor in chief and a leading investigative reporter—responded to a staff protest at the moves by backing Bhatia. And—just a day after ESPN’s Pat McAfee said that the controversial football star Aaron Rodgers had been booted as a guest on his show—Rodgers was back on the show.

- And, after courting recent controversy over Rodgers’s remarks on its air, ESPN is facing a scandal of a different nature after The Athletic reported that it “inserted fake names in Emmy entries, then took the awards won by some of those imaginary individuals, had them re-engraved and gave them to on-air personalities” who were ineligible to receive them. ESPN said the practice was “a misguided attempt” to recognize valued on-air talent, and that it disciplined those responsible following a probe by outside counsel.

Finally, a programming note: This newsletter will be off Monday for Martin Luther King Jr. Day. See you Tuesday.

ICYMI: When contempt of court is deserved

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.