Sign up for The Media Today, CJR’s daily newsletter.

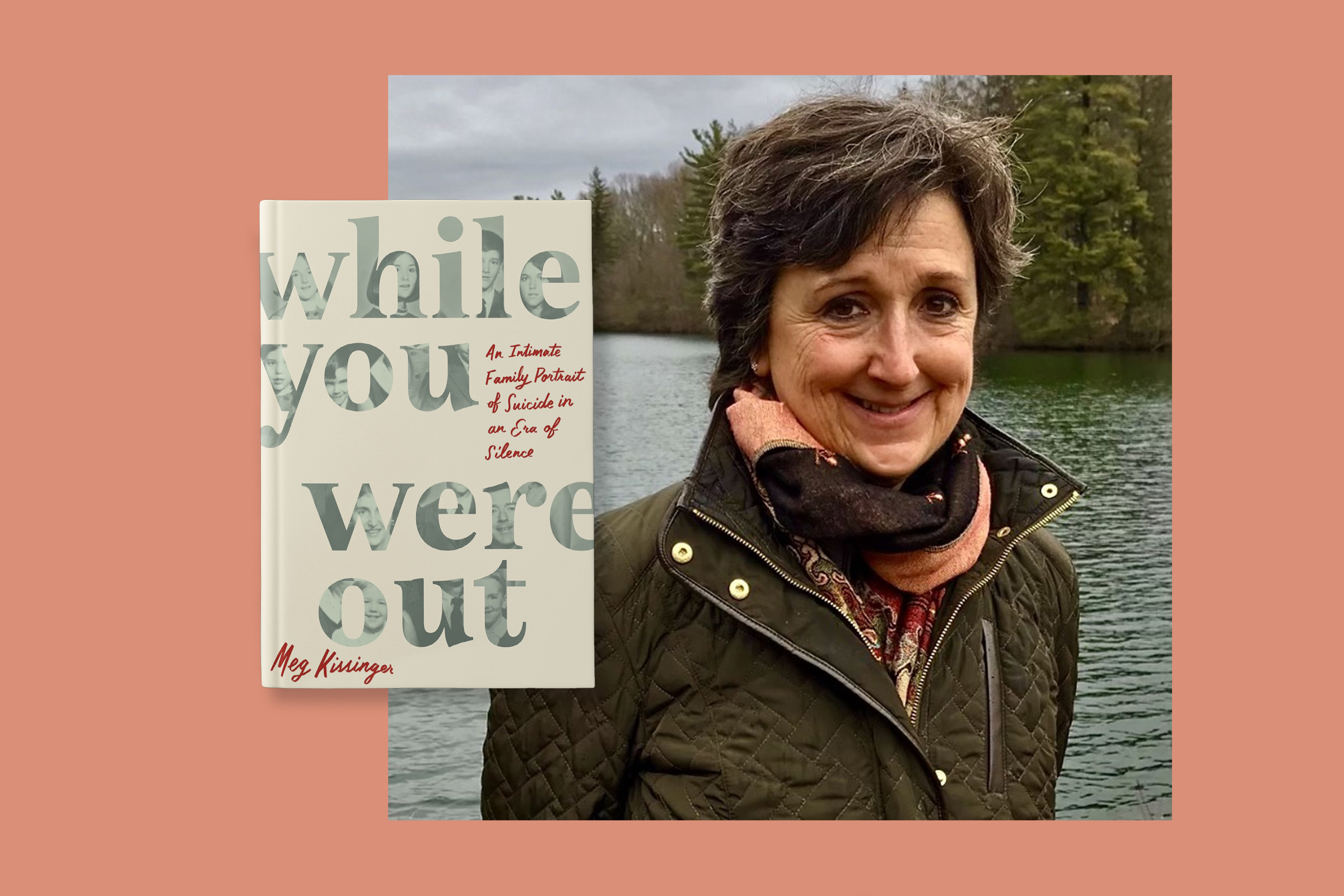

For over three decades, Meg Kissinger’s investigations of the American mental health system for the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel sparked national conversations and meaningful local changes in housing policy for people with chronic mental illness. She is now working to expand the mental health beat, both through a Columbia Journalism School class she teaches on investigating the mental healthcare system and through her work as a trainer with the Dart Center for Journalism and Trauma (which is based at Columbia). Kissinger has also written for CJR explaining why coverage of suicide should focus both on stories of resilience and on exposing the lack of mental health resources available to people who are suffering and their families.

Events in Kissinger’s early life inspired her career. She grew up one of eight children in a loving, rambunctious family from an affluent suburb of Chicago. But privately, her mother and father both struggled with mental illness. Two of her siblings, Nancy and Danny, died by suicide; a third, Jake, lives with serious mental illness. In her new book, While You Were Out: An Intimate Family Portrait of Mental Illness in an Era of Silence (Celadon), Kissinger investigates the history of her own family—a story she and her siblings had never before pieced together. Their mother left Nancy in the care of their thirteen-year-old sister, hours after a failed suicide attempt, only for Nancy to slip out the back door and end her life. Kissinger’s closest sibling, Patty, spent time in a psychiatric ward as she confronted her guilt over Nancy’s death. Their sister Mary Kay secretly terminated a pregnancy in the years before Roe v. Wade.

Through a mesmerizingly personal lens, Kissinger’s book traces the evolution of mental health policy, as well as systemic discrimination against those who need help. Recently, I spoke with Kissinger about how she investigated her own loved ones, why she and her siblings decided to share a story that they’d considered too intimate to fully discover themselves, and how we can better support mental health journalists in the newsroom. Our conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

AD: You said you felt like a “twenty-first-century Charles Dickens” reporting this book, given the horrors that you unearthed. How did you apply the investigative skills you’ve built over your career to this project? You hit some obstacles from the start: you learned that your mother’s medical records had been destroyed…

MK: First of all, the medical records. Even though I couldn’t get my mother’s, I did get my dad’s, and my deceased brother’s and sister’s, including notes from 1976 for my sister from a state mental hospital in Illinois. It was a heavy lift: I had to be declared executor of her estate, which meant that I had to get my surviving brothers and sisters to agree to let me be the executor, which they did, bless their hearts. Once I was declared Nancy’s executor, there came these twelve pages of notes from 1976. That’s not a lot, but what was in there was very telling, even just the language that they used.

Then, of course, police records, from the suicides of my sister and brother, and the coroner’s reports. And the Army has amazing records. Chapter Two of the book goes into the death of my uncle in a plane accident while he was training to become a pilot in World War II. I got witness statements, photographs, and really detailed accounts of that accident. So I just used all the skills that I learned as a beat reporter and filed those Freedom of Information Act requests.

Then, just old-fashioned interviews. I tracked down our nanny from 1961–62, which was not a small thing. That was actually through the alumni office at the college that she went to all those years ago.

The details you learned are just visceral, like a time capsule. A judge told your brother Danny that he’d like to send him to a concentration camp. Nancy’s nurse was so dismissive and unsupportive of her.

That really got me, when I saw that Nancy was described as “needy.” Yes, she was needy—she was in a hospital, for crying out loud. They also described her going to the desk to ask for some aspirin for a headache, and when they said that they couldn’t give it to her because a doctor hadn’t prescribed it, she must have pitched some kind of fit. So they put her in restraints and then injected her with a sedative. It was so reminiscent of, like, One Flew over the Cuckoo’s Nest. It seemed really barbaric to me. It was important for me to know that.

I was just flabbergasted at what I found out about my family, and maybe they about me as well. It seems impossible that we did not sit down as a family and have conversations about our sister who had just died by suicide, and that we were never offered the opportunity to discuss any of this with a therapist. I grew up in a warm, loving, supportive family. But it is very indicative of the era and the environment in which I grew up.

You pin these seminal moments in your family history to major moments in the country’s history.

I was very worried about the reader—there are a lot of characters in this story, so I knew that it was important to anchor the story in these events. I’m a big list-maker; I think that comes from being a reporter and writing some longer narrative pieces over the years. So I made a chronology, really beginning with my grandparents: going back to the nineteen twenties and up to the present day. I also made a separate list of seventy-five scenes: me falling off the pier on a family vacation; me trying to recut my eyes so I could get some private time with my mom; Billy running around naked with the next-door neighbor—little antics and shenanigans in our family. But also, things like President Kennedy signing the Mental Health Act of 1963, and other events that anchor the deinstitutionalization of the psychiatric hospitals around the country and what was going on with mental health policy. I was trying to pair that up with the arc of the mental health issues in our family. Conveniently, Rosemary Kennedy [JFK’s sister] and my mother’s brother were institutionalized in the same facility. So the literary gods were smiling on me a bit and giving me an opportunity to twin these narratives.

How hard was it to get the buy-in of your family? You guys are from Wilmette, Illinois, this small, tight-knit community. Even though you live in different places now, you still have this network of people your family always knew. It’s a very personal story.

The book really is so exposing; I feel like I am running down Fifth Avenue buck naked and getting my brothers and sisters to run along with me. Everybody had something humiliating that was exposed in this book. That was purposeful, because the nature of mental illness is tough, and I wanted to show the collateral damage and how we were all brought to our knees by this. But I also wanted to show how we’ve hung together, which is really remarkable. If my brothers and sisters weren’t the amazing characters that they are, I would not have even attempted this book. But I know them to be gracious and giving people.

Before I wrote a word, I went to each of them and said, I really want to write this book, because as a journalist, I have seen mental illness devastate families. Our family was injured, but not devastated. We have a story to tell that can be helpful to other people, so what do you say? Can we do this? My big caveat was I did not want this to be a memoir by committee: I wasn’t going to have everybody write a little something and have me bring it together. That would have been so boring, and it would have lost its intensity. So I was going to tell it the way I would tell a full-throated investigation. I didn’t know what the hell I was going to find, and that was very scary. It was a huge leap of faith on their part.

I just said two things: First, I’m going to collect everything I can find in a Google Doc, and you can access it if you want. Second, before I send this off to my editor, I want you to read the book. And if there’s anything in there that you can’t live with, let me know. They agreed to that. And nobody had me take anything out. I have a brother who lives in a group home; who lives with serious, persistent mental illness. I was really worried about retraumatizing him. But he ended up being my biggest cheerleader. He said again and again how important a book like this is to show the realities of what families go through.

You’ve been covering mental health your whole life. Has writing this book changed your approach in any way?

I was a hard-charging, pedal-to-the-metal reporter, to my peril. I describe in the book how I really had a breakdown of my own eventually, when I went with a mother and her son out to California. She was desperately seeking help for her son, who was so sick. And it was a fool’s errand—I knew it was not going to end well, and sure enough, it didn’t. The guilt that I felt, and the angst over how much I was contributing to the collapse. The mother ended up in a psych ward, damaged from that whole episode. It made me appreciate the need to calibrate yourself, to pace yourself as a journalist. You can’t help but fall in love with the people that you’re writing about. If you spend so much time with them, you see them in all their humanity. It sounds flabby. It’s not at all; it’s really critical. You’re going to be a better journalist because of it.

Editors need to know this as much as the reporters, maybe more so if they’re going to manage their staff. You have to understand the toll that writing about this takes and give your reporters that time to process it and give it the proper perspective.

What do you think that reporters and their editors are scared of? What do you think stops reporters and their editors from covering mental health more?

I think they are afraid that they’re going to hurt people living with mental illness by writing about them. And really, the opposite is the case. When we ignore all this, the situation festers. I think about David France and his genius book How to Survive a Plague, which is about the grassroots movement to get the federal government to pay attention to the need for a cure for AIDS. It happened because they applied so much pressure. That’s exactly what needs to be done in mental health; we need that kind of groundswell. Journalism has a critical role in this.

We’re starting to see it covered a whole lot more. The Seattle Times now has a mental health desk, and other newsrooms are adding mental health journalists. When I first started writing about this stuff, which would have been in the nineties, I was the loneliest reporter, and now I’m in great company. And my students are so bright; they’re taking such care to write about these things responsibly. So I have great hope. There are stories aplenty. There’s a fantastic website called MindSite News which offers a daily digest of news about what’s going on in mental health reporting.

Let’s say I pitch a mental health story today. Is there anything else I should know to get this kind of story right?

Language. We are very afraid to talk about mental illness as mental illness. We use the words “mental health challenges”; we use really flabby language because it’s still a source of shame. We’ve got to get over that, because it is an illness. It’s debilitating; in some cases, it could be lethal.

The word “stigma” is also a bugaboo. I don’t like that word, and neither do a lot of people—specifically Thomas Insel, who was the director of the National Institute of Mental Health. In his book Healing: Our Path from Mental Illness to Mental Health, he talks about why he doesn’t use the word, because “stigma” suggests that the person living with mental illness is stained in some way and is deserving of being set apart, where what you’re really talking about is “discrimination.” That puts the onus on the person who is not applying equal treatment. I think it’s more inciting; it’s more of a call to action to point out how people who have serious mental illness are discriminated against in places where they live, in the workplace, in the kind of care that’s available to them. So when we start framing it like that, that’s when you start to really write impactfully in the way that journalism does best.

Other notable stories:

- Yesterday, an explosion devastated a hospital in Gaza City, apparently killing hundreds of people, though the death toll has yet to be confirmed. Hamas quickly blamed Israel for the air strike; Israel subsequently pinned responsibility on a botched rocket launch by Islamic Jihad, a group allied with Hamas; as of this morning, investigative journalists were still working to piece together what happened. In other news about the war in the region, the Washington Post explored how Hamas, whose accounts have been banned by most major social networks, is using Telegram and other unmoderated platforms to get its message out and share “grisly first-person video with a level of sophistication not seen in past conflicts.” And the Committee to Protect Journalists updated the death toll among reporters covering the conflict to seventeen. (We wrote about the toll yesterday.)

- Also yesterday, Jim Jordan, the hardline Republican congressman, fell short of the votes he needed to win election as the next Speaker of the House of Representatives. Jordan is expected to try again today but doesn’t look likely to succeed—in part, according to various reports, because his allies’ efforts to strong-arm Republican holdouts into voting for him have backfired. As the Post’s Sarah Ellison and Will Sommer report, some such efforts have come from right-wing media personalities—not least Sean Hannity, who has backed Jordan for Speaker both publicly and, reportedly, in private conversations and emails to lawmakers. Following the vote yesterday, Hannity’s website posted a list of the Jordan holdouts along with their office phone numbers, so that readers might call them.

- The Post’s Meryl Kornfield assessed President Biden’s interactions with the media since taking office, noting that he has granted just one formal sit-down to a traditional print reporter (from the Associated Press) while speaking more proactively to influencers and other nontraditional media figures. “Biden’s aides say they are responding to an evolution in the media landscape, not breaking sharply from precedent,” Kornfield writes. “But critics say that the strategy gives the White House far more control over the message, often letting Biden avoid scrutiny.” (The White House has noted that Biden engages the traditional press in various settings, including on trips and after speeches.)

- Also for the Post, Erik Wemple reports on claims in a new book by Melissa DeRosa, who served as a top aide to Andrew Cuomo when he was governor of New York. Stories by Jesse McKinley, a reporter at the New York Times, alleging sexual wrongdoing on Cuomo’s part helped bring him down as governor—but DeRosa alleges that McKinley himself behaved inappropriately toward her during a meeting. The Times told Wemple that an “independent, external investigation did not substantiate Ms. DeRosa’s characterization of the events,” though the paper did shift McKinley to a different beat.

- And Cheng Lei—an Australian journalist who worked for the Chinese state-backed broadcaster CGTN in Beijing before being jailed for three years on murky national security grounds—gave her first sit-down interview since she was freed last week. Cheng told Sky News Australia that she was jailed because she broke an embargo on an official document by a few minutes. “In China, that is a big sin,” Cheng said. “What seems innocuous to us here…is not in China.”

ICYMI: The toll on the press so far in Israel, Gaza, and Lebanon

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.