Sign up for The Media Today, CJR’s daily newsletter.

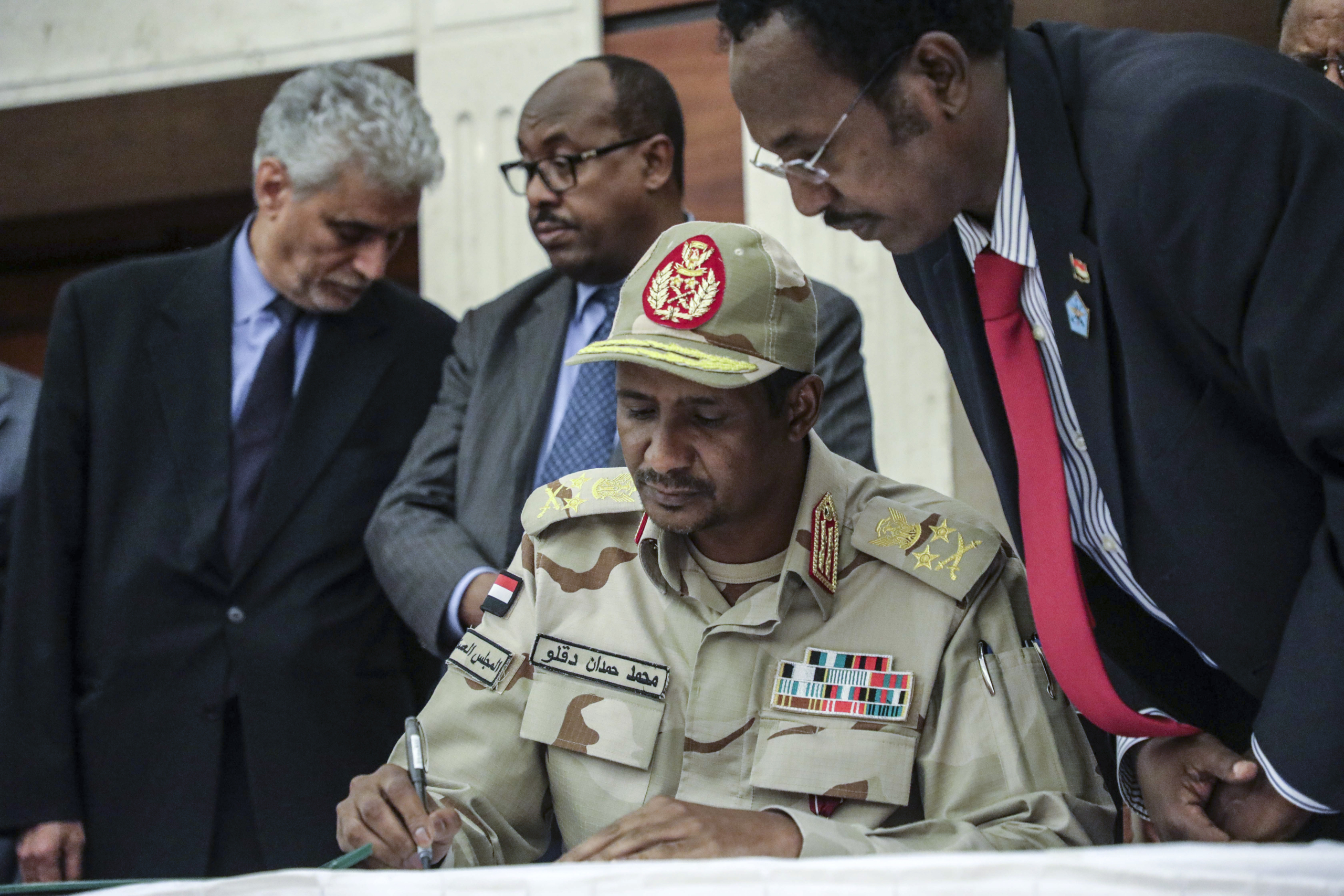

Nine months ago, Sudan’s military and the Rapid Support Forces (RSF), a powerful paramilitary group, unleashed attacks against each other in Khartoum, the capital. Ever since, a destructive civil war has played out in the country; over twelve thousand people have been killed, and more than seven million people have been displaced. The fighting, once contained to the capital and adjoining cities such as Omdurman and Bahri, has spread to different parts of the country, such as Kordofan and Darfur. Tens of thousands of people have fled into neighboring countries including South Sudan, Chad, and Egypt. In December, the RSF captured Wad Madani, a major city that had been a safe haven for thousands who fled Khartoum at the start of the war. While the Sudan Armed Forces (SAF) under General Abdel Fattah al-Burhan still control much of the country, the capture of Wad Madani was a major victory for the RSF and its leader, General Mohamed Hamdan, also known as Hemedti.

Both sides in the conflict have reportedly harassed, beaten, and shot at journalists since the fighting broke out. Many outlets have stopped operating altogether due to the violence. In October, RSF members ran over Halima Idris Salim, a reporter for the independent news site Sudan Bukra, with their car, killing her. In December, the Sudanese Journalists Syndicate reported that the RSF is now using the country’s state television headquarters—which the group has controlled since fighting began—as a detention facility.

In June, after the war began, I spoke with Hiba Morgan, Al Jazeera’s Sudan correspondent. We discussed the context for the fighting, which followed a thwarted transition to democracy and a coup; the coverage of it; and what might happen next. Since then, international media focus on the conflict has waned despite the violence not letting up; indeed, various commentators have dubbed it a “forgotten war.” Last week, I reconnected with Morgan to discuss what has contributed to this loss of attention, how best to communicate the civilian toll, and the challenges that she and other journalists are facing nine months into the war. Our conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

FM: The last time we spoke, around eight hundred civilians were reported killed and about a million displaced. Now over twelve thousand deaths have been reported and over seven million have been displaced. What are your observations on how media coverage and international attention have kept up with all of this?

HM: When you look at what’s been happening around the world, especially in Gaza and Israel, attention has naturally been diverted. But even before that, we saw less media coverage. It’s partly because there are no international journalists in the capital, Khartoum [or] in areas of conflict like Darfur, like Kordofan. It’s not been easy for us to move around Khartoum. On the side of the government or the army, you need an escort for your safety. There’s also tension and anger from civilians; when they see a camera they don’t necessarily welcome you. You need to make sure that you have a security escort so that you are protected in public places. Even people in places like Darfur and Kordofan cannot film because of concerns for their own safety, because of a lack of network [connection] and electricity. All of that has led to the diversion of attention.

Even if there were journalists on the ground—and there was network [connection], and people were allowed to film what was happening in front of them—I’m not sure that that would have changed anything. Sometimes, it’s an issue of how much certain parts of the world matter to you. And I think Sudan, generally speaking, even before the conflicts, has fallen under really low priority.

In addition to the on-the-ground fighting, international actors have taken sides in this war—the RSF has reportedly received support from Russia’s mercenary Wagner Group and the United Arab Emirates, while the SAF has been backed by Egypt. Has enough coverage been devoted to the geopolitics contributing to this conflict?

I don’t think so. I know for a fact, for example, that the RSF is being backed by the UAE, but you don’t hear that a lot; there are only a couple of articles on [it]: one in the Wall Street Journal, one in the New York Times. I think it’s because people—media houses and countries that have influence—don’t want to stir up regional tensions. And there is the belief, politically speaking, of some diplomats that if you act under the table as opposed to outright calling out the backers, you’re likely to reach an easier solution.

At the start of the conflict, the RSF took control of the headquarters of the Sudan Broadcasting Corporation. Now it’s being reported that the RSF has been selling off its broadcasting equipment and using the buildings as a detention facility. Can you talk more about that?

It’s funny that you bring up the state television, because a couple of days ago I was speaking to someone—a civilian—who was detained there. He drew this little map; I wouldn’t say he was the best artist, but he was able to give me a good impression of where the entrance was, and the offices that were turned into the detention centers, and the rooms used for the commander’s office. Whenever he would draw another detention office or part of the building, it was just more and more shocking—the number of sections that have been turned into detention cells that, he said, hold about twenty-five to thirty people in a room. I also heard from many colleagues and friends [about equipment being sold]. One of them called me and said, “I saw something that very much looks like it’s from the state television’s facilities that has been brought out and sold, and for super cheap as well.”

The state television had its issues, but they were working to build it out during and after the revolution [in 2019, when Omar al-Bashir, the long-standing dictator, was overthrown]. Knowing that engineers, journalists, editors have put so much effort into trying to build it into a better television station, with better facilities and better broadcast capabilities, and now hearing that all these places have been turned into detention centers, it’s just surreal. It will take a lot of effort to rebuild it once the war ends. During the first days [of the war], many journalists who were working there were detained at their place of work. So it will be traumatizing for a lot of them to come back, I imagine. I don’t know how many people would be willing to go back to the place where they used to work and then later were detained.

Is the RSF trying to use the facilities in any sort of media capacity?

I think the RSF understands that it’s not television as much as social media right now. They have these little videos on social media, whether it’s on Facebook, Telegram, TikTok, X (formerly Twitter). With most of their videos, you can see that they’re tailoring them for social media. They probably have specific WhatsApp groups [where] things are picked up and then put on their pages by their official first units or comms teams. And that’s how it goes [out] really fast.

It’s typical RSF propaganda. You hear their songs, their achievements, as they would put it: We’ve been able to deliver aid to this part of Khartoum; the former regime did [such and such]. Their wording and their messaging is very clear: We are here for you; we’ve been trying to protect civilians; we’re trying to protect your democracy and your protest movements. Never mind that the protesters clearly said they didn’t want them [the RSF]. I listen sometimes to find out what they’re saying, but it’s unclear how many people listen to them.

The SAF during the first days of the war had an army spokesperson who released statements, but that has largely stopped. They’re also on social media.

We previously discussed how vital social media platforms like WhatsApp are for civilians, who need up-to-date information for safety. As a journalist, do you find yourself taking on two distinct roles, getting out vital information while also communicating the larger acts of the war to the world?

We definitely do want to give updates on what’s happening, whether it’s brief or whether it’s through a report that we’re airing or an article. But I think it does take time to absorb what you’ve seen or heard. Sometimes, going through the footage, you realize you’ve documented some kind of crime—what could potentially be a war crime or a crime against humanity. You’re trying to figure out if your documentation is needed for accountability, for justice in the future. We’ve reached a point where we’ve realized—because this war has gone on for so long, and because it’s even in the capital itself, and because of the many horror stories that you hear—that this will require a legal action bigger than the nation can provide when it’s done; we realize that we will need external help with the amount of crimes that have happened. There are journalists that have reached the point where they know that they have to report and tell the audience and viewers what’s happening, but they’re also aware that they’re documenting what potentially are the very first accounts of war crimes and crimes against humanity that could fall under international jurisdiction.

In terms of documenting the atrocities—attacks on civilians and rampant sexual and gender-based violence—journalism can sometimes fall short of capturing the gravity of the situation. Has this been a challenge while reporting?

I think it’s always there. Even before the war, when we spoke to displaced people and refugees who had been affected by the crisis in the country, they told you their story and you ended up picking specific clips to keep it interesting. You don’t want to just make it about one person; you’re trying to portray a bigger picture there; so, out of somebody speaking to you for about twenty minutes, you end up taking only two minutes of it. But then you feel like you’re taking some originality out of the story, some of the pain from the story. It seems like you’re trying to sanitize it, in a way; that’s how I sometimes feel. The story is still the same, but there’s this feeling—for me, at least, and for some colleagues when we speak about this—that you know that you’ve not done that person justice because you’ve not portrayed the whole picture. You’ve given them less than what they deserve.

Other notable stories:

- The fallout from Donald Trump’s blowout victory in Iowa continued yesterday, as the remaining candidates in the race (mostly) turned their attention to New Hampshire, which will hold its presidential primary next week. Ron DeSantis did a town hall on CNN; Nikki Haley appeared on the same network, but said that she would not participate in a pre-primary debate with DeSantis, scheduled for tomorrow night on ABC and WMUR, unless Trump, who has skipped every debate so far, pledged to appear, too. The debate was ultimately canceled; it’s unclear if a weekend debate on CNN will go ahead either. Meanwhile, Trump was in New York to witness jury selection in a case brought against him by the advice columnist E. Jean Carroll; the jury will determine how much Trump owes Carroll after a judge found him liable for sexually abusing and defaming her.

- Fallout continued, too, from Alden Global Capital’s surprise sale of the Baltimore Sun to David D. Smith, a Maryland businessman who serves as the executive chairman of the broadcast chain Sinclair and has been linked to various conservative causes. According to the Baltimore Banner, Smith took part in a “tense, three-hour meeting” with Sun staffers during which he admitted to only rarely reading the paper, stood by past comments calling print media “so left-wing as to be meaningless dribble [sic],” refused to reassure staffers about their jobs, asked them to rank each other, and told them to “go make me some money.” Nieman Lab’s Joshua Benton asks whether Smith could be an even worse owner than Alden, which had long been thought to represent “rock bottom.”

- The Wrap’s Sharon Waxman and Alexei Barrionuevo dug into the abrupt recent resignation of Kevin Merida, the editor of the LA Times, amid reported tensions with Patrick Soon-Shiong, the paper’s owner. Merida’s departure shocked staff, Waxman and Barrionuevo report, but perhaps shouldn’t have; in interviews with half a dozen sources, “it became clear that Merida’s relationship with Soon-Shiong—though never close—had broken down irreparably by the end of last year over the owner’s interference in newsroom decisions, a lack of support for Merida’s independence as editorial leader and ongoing financial losses with no apparent plan to reverse them.”

- Recently, we wrote about a spate of arrests targeting journalists in Azerbaijan. The crackdown has since continued: this week, officials arrested Shahin Rzayev, a political reporter for JAM News, and ordered three months of pretrial detention for Elnara Gasimova, of Abzas Media, an investigative outlet that has been particularly hard hit. Meanwhile, Voice of America’s Liam Scott and Alex Gendler spoke with two journalists who have been the victims of crimes in neighboring Georgia after reporting critically on Azerbaijan, fueling concerns that the latter may be targeting critics beyond its borders.

- And the Sydney Morning Herald reported this week that the Australian Broadcasting Corporation sacked Antoinette Lattouf, a broadcaster who had posted tweets critical of Israel, last month following a coordinated letter-writing campaign from pro-Israel lobbyists. A senior ABC executive told staff that outside pressure was not to blame for Lattouf’s dismissal, but many employees were not satisfied by his explanation and have threatened to go on strike. Lattouf has filed a claim for unlawful termination.

ICYMI: Blowing hot and cold in Iowa

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.