Sign up for The Media Today, CJR’s daily newsletter.

Earlier this month, Jacob L. Nelson wrote in a piece for CJR about how the American Jewish press has interpreted changes within the community precipitated by Hamas attacking Israel on October 7, 2023, and Israel’s bombardment of Gaza that followed. He described a period of fragmentation, with American Jews critical of Israel moving decisively away from a mainstream establishment that no longer felt like their political home. Meanwhile, some Jewish groups previously aligned with progressive coalitions have found themselves feeling betrayed by former allies who refused to denounce the murder of civilians on October 7. The war in Gaza, Nelson wrote, “did not create a rift so much as intensify an existing one.”

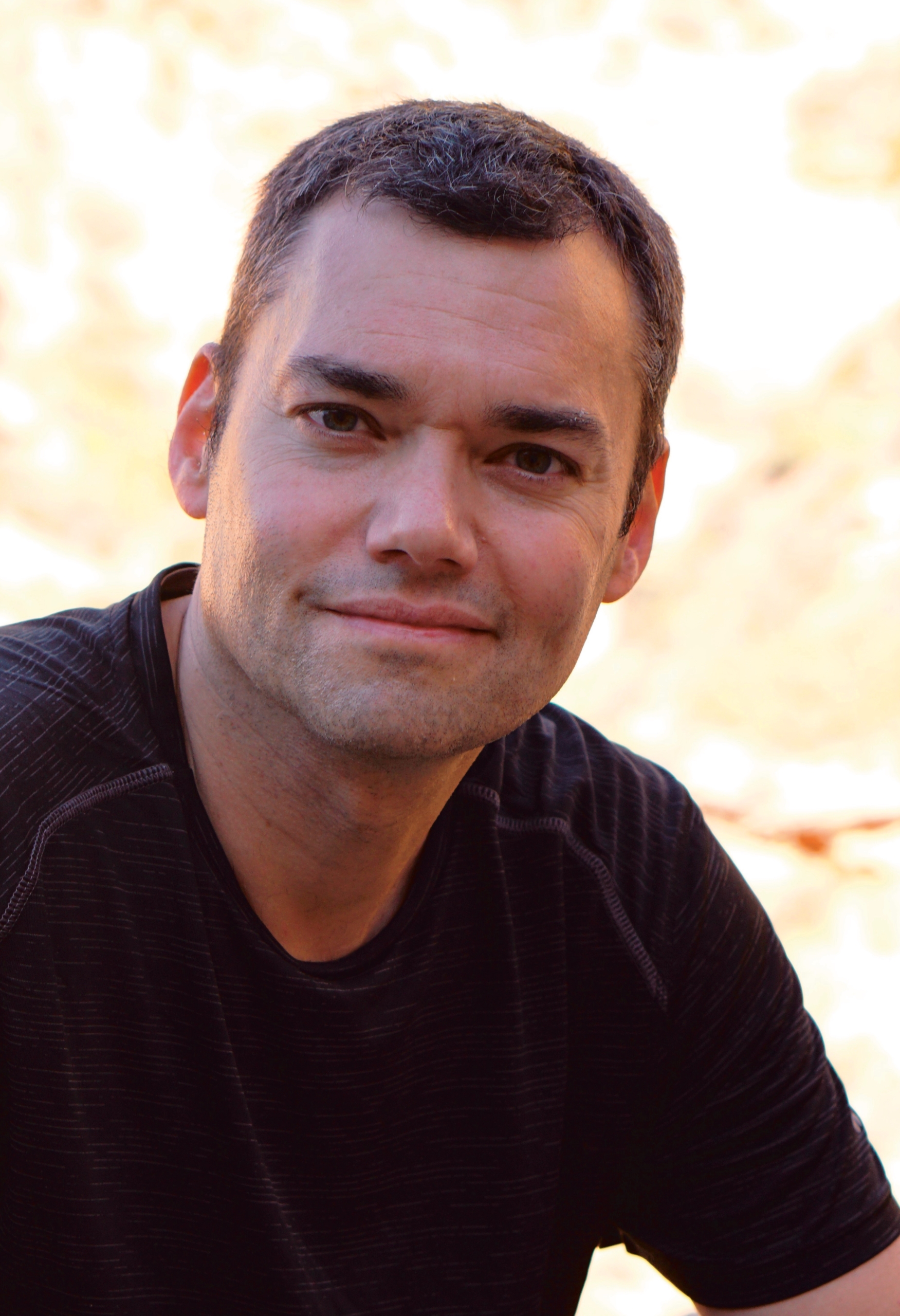

Over the past fifteen months, Peter Beinart has found himself struggling to bridge this very divide. Beinart, a former editor of the New Republic who has written for the New York Times, The Atlantic, and Israel’s Haaretz (among many other publications), currently teaches journalism and political science at the City University of New York and serves as editor at large for Jewish Currents, which describes itself as “a magazine committed to the rich tradition of thought, activism, and culture of the Jewish left.” After undergoing a political transformation of his own, Beinart has become known in recent years for his critique of Israel’s ongoing military occupation of the West Bank and Gaza, and of the politics of Jewish supremacy. My introduction to his work was a 2021 article in Jewish Currents in which he argued against de jure Jewish statehood and in favor of a binational, one-state solution in Palestine and Israel.

Beinart is also a strictly observant Jew. As the war in Gaza unfolded, he told me, “it was surreal to feel just horrified day after day by what I was seeing and then to see the organized Jewish community reacting with support.” Beinart saw something deeply wrong with the emphasis on Jewish victimhood and with the idea that the incursion into Gaza was an act of Jewish self-defense: “It struck me as having the effect of giving people a set of rhetorical strategies to allow them not to feel, and to allow them not to see,” he said. And so he wrote a book, Being Jewish After the Destruction of Gaza: A Reckoning, which came out yesterday. In it, he argues that Jewish safety should not—indeed, cannot—come at the expense of Palestinian dignity. “We must now tell a new story,” he writes in the book’s prologue. “Its central element should be this: We are not history’s permanent virtuous victims.” Beinart and I spoke in advance of the release of the book about the politics of word choice, writing for a skeptical audience, and the Palestinian texts that have shaped his thinking. Our conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

YRG: Over the past fifteen months, the media has struggled with the fact that, when it comes to contested narratives, even the use of certain words can be loaded—for example, “terrorist” versus “militant” versus “fighter.” How did you navigate that in writing this book?

PB: I try to avoid words that are going to lose people, [where] the particular definition isn’t necessarily that important, but they signal you are anti-Israel and therefore I don’t trust you and I’m not going to listen any further, whether that term is “apartheid” or “settler colonialism” or “genocide.” I would actually defend particular definitions of all of those terms for certain things that Israel does, but I avoid them generally because I think it’s more effective to lay out the facts as I see them: in the West Bank, Jews and Palestinians live alongside one another, but Israeli Jews have citizenship and the right to vote in the state that controls that area; they live under civil law and they have freedom of movement. Palestinians don’t have those things. I think that constitutes apartheid, but I think it’s more effective to say, You can call that what you want, but do you think that’s an equal legal system? Similarly, on the question of genocide: we know that [in Gaza] Israel has destroyed most of the hospitals, most of the schools, most of the agriculture, most of the buildings; that people have been displaced multiple times and that the number of people, including the number of children, who have died, is well in excess of many of what we would consider the most horrifying conflicts of the twenty-first century. If you don’t want to call that genocide, don’t call it genocide. But what do you think of that state of affairs?

In the book you talk a lot about the strength that comes from ordering your life around community, but you also describe the dangers of the kind of defensive tribalism that the Jewish community has, in many ways, assumed. Has the press, both Jewish and otherwise, contributed to this dynamic? Have you seen this change at all over time?

It’s no surprise that Palestinians have not had much of a voice in the American discourse about Israel and Palestine. It was in 1982 that Edward Said famously said Palestinians lack permission to narrate; I think in the mainstream American press, to a large degree, they still lack permission to narrate. I think what has changed is that the press is fragmented, with the rise of social media, and that there is now a wing of Americans—younger, more on the left—who do hear Palestinian voices more because Palestinians have used social and alternative media.

Establishment Jewish perspectives are well represented in mainstream American public discourse. There’s often a centering of Jewish and Israeli humanity, which I don’t want to take for granted; I’m aware that that hasn’t always been the case, and that Jews have suffered a great deal from dehumanization. What’s bittersweet to me is the way in which empathy for our experience and our story comes at the expense of Palestinians. [When speaking about the Holocaust, many people, Jews and non-Jews, say] We will never allow this to happen to Jews again, and We support the state of Israel, and We support Jews being safe. I feel, on the one hand, grateful to live in a country that centers that narrative. It’s part of the reason I feel so comfortable as an American, even in comparison to other liberal democracies like in Europe, where I think that story may not be as central. On the other hand, it’s so clear to me that the effect of that story is to decenter a narrative in which Palestinians have been dehumanized, for which the people in power in media and government don’t feel that same sense of obligation. Or the conversation about anti-Semitism: I’m glad there is a sensitivity in American discourse to anti-Semitism. And yet I’m also appalled by the degree to which anti-Palestinian racism is simply the air that we breathe, without recognition that that should also be considered an unacceptable bigotry. I think the organized American Jewish community weaponizes that language of concern and empathy in cynical ways, and uses it as a tool to try to shut down a conversation about the rights and dignity of Palestinians.

When you write something that you anticipate might touch a nerve within your community, how do you prepare for the pushback?

Sometimes I’ll send things to friends whose politics are not mine, just to kind of get a preview of what they’re going to dislike. It can help me avoid a kind of unforced error in which I said something that didn’t come across the way I wanted it to or I didn’t anticipate some counterargument. For instance, I sent this book to a friend who said to me, You know, Peter, you’re not taking enough account of the fact that there are people who, at the end of the day, support the war, but are still deeply, deeply pained by what they see in Gaza. I thought that was a really helpful point to make, that I then tried to emphasize more. I think the other thing I do is I try in difficult moments to just sit quietly a little bit and ask, to the degree that I can, whether I think that I’m doing what God wants me to do. It doesn’t mean I can control the reaction. It just means I’m willing to accept the response.

The history of persecution has made it so there is a strong cultural taboo against speaking or writing publicly about things that are challenging within the Jewish community—as you and I are doing now. How do you respond to that critique?

The critique that essentially I’m airing dirty laundry—making Jews look bad and giving aid to people who hate Jews? I do hear that a lot. It seems to me we have a tradition of speaking really openly and often quite harshly about ourselves because we believe that actually we have a moral responsibility to try to do better in living up to the obligations of the mitzvot—commandments—however one interprets that. The other thing is that I’ve never met a Palestinian or a pro-Palestinian activist who has said to me, Gosh, I really didn’t know Israel was doing these bad things; I wasn’t really upset about it until I read you. People are seeing these things all the time, and frankly they’re often seeing them in much more unvarnished, harsher terms than I’m expressing them in. In fact, some of what I’ve heard repeatedly from Palestinian or Arab Muslim interlocutors is along the lines of: When Jews stand up for Palestinian human rights, they effectively counter anti-Semitic narratives in the Palestinian, Arab, and Muslim world because essentially they make it harder for people to conflate Israel as a state with all Jews. They send a message that this is not a tribal struggle; it’s a struggle about certain principles.

In an announcement about your book, you wrote that you hope that your readers will also seek out Palestinian authors. Can you recommend a couple of books in particular?

One book—an old book, but a classic—that had a really big impact on me is Said’s The Question of Palestine. The book helped to get Western readers to see Zionism from what Said calls “the standpoint of its victims,” which is still something that is relatively rare. The other thing that really affected me in all of Said’s writing is the ethical humanism of his perspective. He has the extraordinary capacity to critique Zionism and also understand why Zionism had an appeal to so many Jews; to understand the Jewish experience that would have led some people to embrace Zionism and also to accept the depth of the Jewish connection to what Jews call the land of Israel. I think that takes a tremendous amount of empathy: Said is writing as a Palestinian who is from a family that was dispossessed, as part of a people who are not only dispossessed, but whose dispossession is not acknowledged.

Another book that had an impact on me was Ali Abunimah’s One Country. What impacted me was his effort to argue that [Palestine and Israel] could be a place of collective liberation. I think it’s so alien to mainstream Jewish discourse to imagine that a Palestinian writer would care about Jews living and thriving [with Palestinians] in one equal country. The spirit behind it was one that was helpful to me as I made a move that was scary for me, away from the idea of partition toward the idea of equality in a shared space.

Editor’s note: On Monday, Ali Abunimah, the journalist mentioned above and executive director of the online publication Electronic Intifada, was deported from Switzerland after several days in administrative detention. He had traveled to the country to give a talk. According to Reuters, Swiss police cited an entry ban as the pretext for Abunimah’s detention. He said on X after his release that he had not been presented with any charges, adding that he was questioned by Swiss defense ministry intelligence agents without a lawyer present; he suggested that he was targeted for being a journalist who has written about genocide in Palestine. Two high-profile representatives of the United Nations said that Abunimah’s detention raised serious concerns about freedom of expression.

Other notable stories:

- Yesterday, Karoline Leavitt, the new White House press secretary, hosted her first formal press briefing and indicated a desire to shake up the way such events typically work, assigning seats for representatives of the “new media”—the first questions went not to the Associated Press, as is traditional, but high-profile journalists from Axios and Breitbart—and repeatedly encouraging podcasters and online content creators to apply for credentials. (Leavitt also pledged to restore hundreds of credentials that she said were “wrongly revoked” by the Biden administration.) The briefing “reaffirmed a truism about the Trump White House: His aides perform for an ‘audience of one,’” CNN’s Brian Stelter writes (referring to Trump himself). “Leavitt seems instantly well-suited to the task,” “expertly channeling” Trump and using “many of the same rhetorical tendencies.”

- For CJR, Jim Newton, a longtime former reporter and editor at the LA Times, compared Patrick Soon-Shiong—the medical billionaire who currently owns the Times, and has recently courted controversy for sounding off about national and local politics—with the paper’s other owners down the years. Soon-Shiong “does not have a voice in civic life because he built a great newspaper. He bought a great newspaper and now thinks it gives him expertise in civic life. It doesn’t,” Newton writes. Amid the devastating recent wildfires in Los Angeles, “the city is struggling. His staff is performing nobly. He’s shrieking and posting false claims on X.” (Soon-Shiong caused controversy on X again yesterday when he endorsed Robert F. Kennedy Jr. for health and human services secretary.)

- We noted in yesterday’s newsletter that Jim Acosta, the CNN anchor and past Trump antagonist, was expected to leave the network after being moved from his time slot; he subsequently confirmed as much on air, and announced that he’s launching an independent venture on Substack. (“Don’t give in to the lies,” he said on his way out.) In other media-jobs news, a group of editors at the Wall Street Journal are reportedly out of a job following a restructuring. SiriusXM is reportedly cutting around a hundred jobs across the company. And Katrice Hardy, currently the executive editor of the Dallas Morning News, will take on the newly created role of CEO at the Marshall Project.

- Last week, eight state senators in Hawaiʻi sponsored legislation that would create a state-run Journalistic Ethics Commission with the power to investigate complaints against members of the press and impose punishments on those found to have violated ethical standards. The bill quickly set off alarm bells among journalists in Hawaiʻi, and this week, the Society of Professional Journalists—whose code of ethics is cited in the bill—came out strongly against it, describing it as “patently unconstitutional” and noting that the SPJ code is “guidance for journalists rather than rules requiring compliance.”

- And, over the weekend, an Israeli soldier struck Aaron Boxerman, a reporter for the New York Times, with the muzzle of a loaded rifle, then pointed the gun at Natan Odenheimer, a second Times reporter, even after he had identified himself as a journalist; the pair were covering a gathering at the Jerusalem home of a Hamas member who had just been freed from jail as part of the recent ceasefire deal between Israel and Hamas when the military raided the property and broke up the event. The Israeli military said that it regretted any harm to journalists and that it was investigating.

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.