Sign up for The Media Today, CJR’s daily newsletter.

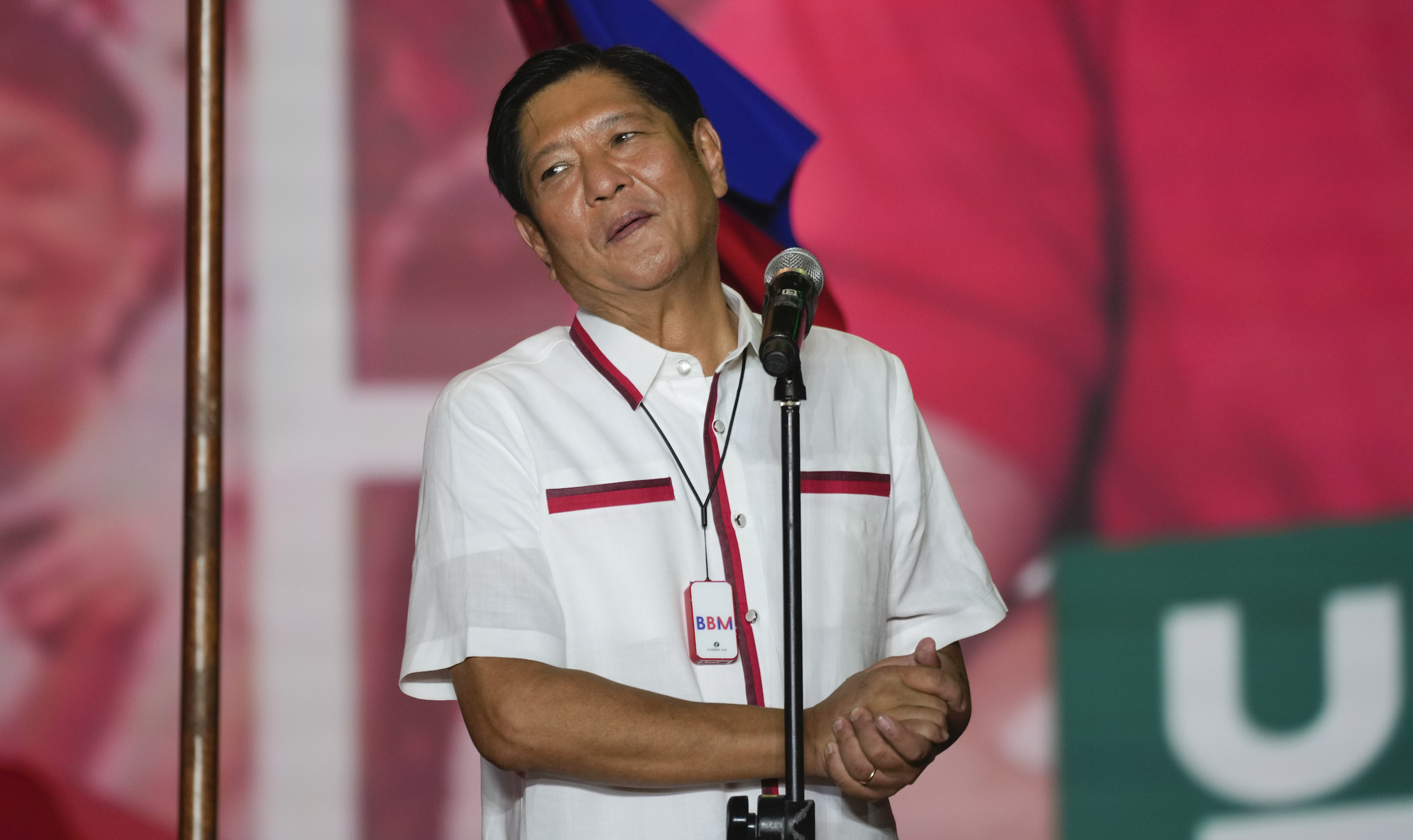

The Philippines will soon have a new president, and it looks like his name will be Ferdinand Marcos—not the country’s former dictator, who died in exile in 1989, but his namesake son, who also goes by “Bongbong.” The count continues—and claims of irregularities, including ballot tampering, have flooded in—but preliminary election results show Marcos with a clear lead over his opponent, Leni Robredo, the current vice president. Rodrigo Duterte, the current president, backed Marcos; Duterte’s daughter Sara ran for vice president on Marcos’s ticket and looks set to win as well. The two families have “effectively formed a dynasty cartel” that could share power for decades to come, Aries Arugay, a political science professor, told the New York Times. “The Philippines is heading more and more toward an electoral autocracy.”

This is an ominous prospect for journalists in the country, who were already working in perilous conditions. When I last wrote at length about press freedom in the Philippines, nearly two years ago, the prominent journalist Maria Ressa and a former colleague at Rappler, her news site, had just been convicted of cyber-libel after retroactively fixing a typo in an article published before the cyber-libel law was even in effect—a significant development in Duterte’s broader war against the press. Since then, Ressa, who has appealed her conviction, and her site have faced a further barrage of legal complaints, while Rappler and other newsrooms have faced cyberattacks. In the same period, no fewer than six journalists have been shot dead, one of them by soldiers at a military checkpoint—part of a much broader pattern of murders in the Duterte era. The Philippines remains high on the Committee to Protect Journalists’ impunity index of countries where the killings of journalists have gone unsolved. Late last year, Ressa and the crusading Russian editor Dmitry Muratov shared the Nobel Peace Prize as representative examples of the threats facing journalists worldwide.

ICYMI: The ongoing information war over Ukraine

In addition to Rappler, Duterte waged war on ABS-CBN, the Philippines’ biggest broadcaster, with allied lawmakers forcing it off air two years ago this week after refusing to renew its license. The network had gone dark once before—in 1972, when Marcos Sr. declared martial law shortly before his mandated term was set to expire. He alleged that ABS-CBN was in cahoots with communists and arrested Geny Lopez, the network’s president, on charges of conspiring to assassinate him. And such tactics were not reserved for ABS-CBN. The Marcos Sr. regime squelched the independent-media landscape, shuttering some outlets and placing others under pliant ownership; many journalists were thrown in jail, while some foreign correspondents were expelled or denied visas. Toward the end of the Marcos Sr. era, independent outlets—led by smaller papers that kept running and were dismissed by Marcos Sr. as the “mosquito press”—started to reassert themselves. In 1986, as a popular uprising swept Marcos Sr. and his family out of power, “many of the key street battles centered on radio and television stations,” CPJ has reported, with the regime collapsing after it “lost control of its main television station, Channel 4.”

The younger Marcos served as governor of Ilocos Norte province under his father’s dictatorship, and was also named chair of a national satellite-communications company; after going into exile alongside his father, Marcos returned to the Philippines, becoming governor of Ilocos Norte again in the nineties before serving as a national lawmaker. According to Rappler, Marcos shied away from the press as governor, with surrogates, including a sometime radio broadcaster, speaking on his behalf. His approach, it seems, did not change as a presidential candidate, with Marcos avoiding debates and routinely dodging reporters on the campaign trail (Rappler’s Lian Buan says that a Marcos guard manhandled her as she tried to ask a question); at his first press conference, in late April, his campaign controlled access and screened questions in advance. (He did sit for an interview with CNN, during which he denied dodging scrutiny and said he would engage directly with the press if elected.) According to Buan, the campaign gave privileged access to friendly media figures, including influencers and vloggers.

Reporters who were able to ask tough questions of Marcos were often trolled on social media; after Howard Johnson, a BBC correspondent, asked Marcos if he could be “a good president if you don’t answer serious questions,” he found himself on the receiving end of death threats and claims of foreign meddling. This all reflects a continuation of Duterte’s tactics. The outgoing president leveraged online troll farms to spread lies and pound on his critics; Marcos has denied doing likewise, but has, in reality, been a huge recent beneficiary of disinformation in a country that is very online. Much of this has cast the dictatorship as a golden age, whitewashing its rampant human rights abuses and corruption—a narrative that has taken root not just on Facebook, the locus of Duterte’s viral power, but across Wikipedia, YouTube, and TikTok, where footage of Marcos Sr. and his wife, Imelda, has been glamorized and set to modern music; in one viral challenge, users have recorded older relatives bopping to an old martial anthem. As the Washington Post’s Regine Cabato and Shibani Mahtani have noted, TikTok is not only harder to moderate than text-centric platforms, like Facebook, but has a younger user base with no direct memories of the dictatorship.

As Sheila Coronel, a professor at Columbia Journalism School, put it in a recent interview with GMA News, in this internet age, authoritarian leaders, and not just in the Philippines, have been able to develop new strategies for controlling the flow of information. “It’s no longer withholding of information, no longer censorship as it was during Marcos [Sr.]’s time when there were literally censors sitting in newsrooms and saying, You cannot do this,” Coronel said. “It’s no longer controlling the flow of information, but flooding the information space with so much disinformation and untruths and propaganda, so people are no longer able to discern what is fact and what is not.” Journalists, she added, get “drowned out in that deluge.”

Of course, this is not to say that old-school censorship tactics have gone away; as Coronel noted, restrictive statutes like the cyber-libel law remain a “gun in the holster” for the authorities to use. If there are chilling parallels between the rule of Marcos Sr. and the impending rule of his son, both politically and for the press, it’s also possible to see then and now as being tangled up together in an ongoing process of memory manipulation, with new technologies weaponized to rewrite old truths. As Ressa put it in a recent interview with CNN, the election result is showing “not just Filipinos but the world the impact of disinformation on a democracy.” Marcos, she added, “will determine the future of this country but simultaneously its past.”

Below, more on the Philippines and press freedom worldwide:

- The Philippines: In 2019, Ressa wrote for CJR about being targeted by Duterte. “It was the late eighties when I started my career as a journalist, covering Southeast Asia’s transition from authoritarian rule to democracy. It’s bizarre now to think of the euphoria then,” Ressa wrote. “Decades later, I’m in shock about what’s happening to my country. We are walking back to rule by hostile dictator, witnessing the erosion of our freedoms, becoming accustomed to murder. In the Philippines, 97 percent of people are on Facebook—Facebook is our internet—so as Duterte’s administration and its proxies astroturf social media with propaganda, a lie told a million times becomes the truth.”

- Sri Lanka: Amid deteriorating economic conditions and following months of massive protests that culminated in government supporters attacking their opponents this week, Mahinda Rajapaksa, the prime minister of Sri Lanka, resigned yesterday; his concession, the Times reports, “moved the protesters a step closer to their goal of ridding the government of the Rajapaksa family,” which has dominated Sri Lankan politics for years, though Mahinda’s brother Gotabaya, who has been accused of coordinating the murders of journalists, remains the president. Sri Lanka has a poor recent record on press freedom under the Rajapaksas, and numerous journalists have been arrested or injured during the recent wave of protests.

- Mexico: Yesterday, officials in the Mexican state of Veracruz announced that two local journalists, Yessenia Mollinedo Falconi and Sheila Johana García Olivera, had been fatally shot. A week and a half ago, CJR’s Paroma Soni published an exhaustive piece on the eight Mexican reporters killed so far in 2022, noting that this is already the deadliest year on record for the country’s press; since then, three more journalists have been killed, bringing the total to eleven. Last night, hundreds of journalists gathered in Mexico City to protest the killings. “It’s a whirlpool,” Griselda Triana, whose husband, Javier Valdez, was killed in 2017, told those present. “The crimes against freedom of expression keep occurring every day. We shouldn’t tolerate it.”

- Canada: In November, police in Canada arrested Amber Bracken, a photojournalist, and Michael Toledano, a documentary filmmaker, as they covered opposition to a pipeline development on Wet’suwet’en land in British Columbia. Bracken and Toledano were detained for several days and then released, and the pipeline company ultimately declined to press charges. Yesterday, The Narwhal, a nonprofit environmental-journalism outlet, reported that, shortly after their arrests, a police official claimed in an internal email that the journalists were “advocating and assisting the protesters.” Bracken told The Narwhal, “The idea that powerful people are maligning me behind my back is creepy.” ICYMI, Luke Ottenhof wrote recently for CJR about press freedom issues and land defense efforts in western Canada.

Other notable stories:

- The Pulitzer Prizes were awarded yesterday. The New York Times won in three categories, including for its coverage challenging official narratives about the civilian toll of US air strikes overseas. The Washington Post and a team from Getty Images won for their coverage of the insurrection, the latter sharing the Breaking News Photography prize with Marcus Yam, of the LA Times, for his work in Afghanistan, while a Reuters team including Danish Siddiqui, who was killed in Afghanistan last year, won for images of covid in India. Other winners included the Miami Herald, the Tampa Bay Times, the Houston Chronicle, the Kansas City Star, the Better Government Association and the Chicago Tribune, Futuro Media and PRX, Quanta Magazine, Insider, and The Atlantic, while the journalists of Ukraine were given a special citation for their war coverage.

- NPR’s David Folkenflik reports on growing calls for the New York Times to return the Pulitzer awarded to Walter Duranty, its chief correspondent in the Soviet Union, in 1932 in light of subsequent revelations that he helped cover up a devastating famine in Ukraine after the Stalin regime confiscated food; the Times has long since disavowed Duranty’s work, but the Pulitzer board has opted not to rescind his award, and doesn’t seem set to change its stance now. In other news about Ukraine, the Post launched a searchable database of verified, on-the-ground footage of the war in the country; it already contains more than two hundred videos. And the Cannes Film Festival has denied accreditation to journalists from Russian outlets that do not oppose the war.

- With the Supreme Court set to strike down Roe v. Wade, the NewsGuild-CWA, a leading media union, reiterated its position that access to abortion is a “crucial human right,” and pledged to develop “proposed contract language that provides coverage for abortion care in collective bargaining agreements so workers will be protected regardless of what the Supreme Court and state legislatures decide.” In other media-union news, the BuzzFeed News union ratified its first contract after a lengthy dispute with management. And unionized staffers at Time magazine said they will strike for the day on May 23, the launch date for the annual Time100 list, unless bosses agree to a contract by then.

- The Post published an excerpt from His Name Is George Floyd: One Man’s Life and the Struggle for Racial Justice, a biography of Floyd by the Post reporters Robert Samuels and Toluse Olorunnipa that is due out next week. The excerpt details, for the first time and based on extensive interviews with his friends, how Floyd spent the final hours of his life before Derek Chauvin, a white police officer, murdered him. “On Memorial Day 2020, Floyd left this house in Minneapolis to buy grilling supplies,” Samuels and Olorunnipa write. “He met up with his friend. Then they walked into a corner store.”

- For The Atlantic, Samhita Mukhopadhyay reflects on the impending closure of Bitch and what it says about the state of feminist media. “You’re now more likely to see pockets of feminist writing in a lot of different places across media,” she writes, but this distributed model “lacks what dedicated spaces like Bitch gave us: the conviction of being part of a community with a shared purpose, clear models for writing persuasively about feminist politics, and the unwavering coverage that a mission-driven publication can provide.”

- Last week, the News Media Alliance, traditionally a newspaper trade group, approved a merger with the Association of Magazine Media. “Industries that once seemed distinct in format, content, frequency and distribution have become much more similar in the digital era,” Poynter’s Rick Edmonds reports. “And they find common ground for lobbying,” with both pushing tech platforms to compensate publishers, and bargaining on postal rates.

- According to The Information’s Sylvia Varnham O’Regan and Jessica Toonkel, Meta, the parent company of Facebook, is considering slashing the amount of money it gives to news organizations as the company looks to cut costs and reevaluates including news in Facebook’s app. The dreaded pivot to video could make a comeback.

- According to the Daily Beast’s Noah Kirsch and Andrew Kirell, a news site called The Business of Business, which grew out of a data-crunching tech startup called Thinknum, is in turmoil after staffers “mysteriously stopped receiving their paychecks.”

- And the Times was embroiled in a two-correct-Wordle-answers controversy again, this time after trying to nix “fetus” as a solution due to its unacceptable topicality. Me neither.

ICYMI: The coverage of Rodney King and unrest in LA, thirty years on

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.