Sign up for The Media Today, CJR’s daily newsletter.

Last night, President Biden finally addressed the nation on his decision to drop out of the presidential race and endorse his vice president, Kamala Harris. “I’ve decided the best way forward is to pass the torch to a new generation,” he said. “I know there was a time and a place for long years of experience in public life. There’s also a time and a place for new voices, fresh voices—yes, younger voices. And that time and place is now.”

Biden, of course, wasn’t talking about his presence on social media, where younger voices like to make themselves heard. But he could have been. In the past, his more online supporters have done their best to create memes that might go viral, whether it’s Joe eating an ice cream with his sunglasses on or Joe behind the wheel of his yellow Corvette giving a thumbs-up sign. For CJR’s recent Election Issue, Linda Kinstler wrote about the young activists behind an organization called the Center for New Liberalism, one of whom created several “Dark Brandon” memes depicting Biden as a kind of superhero shooting lasers from his eyes. The name Brandon is a reference to an incident in 2021 in which the crowd at a NASCAR event yelled “Fuck Joe Biden!” but a reporter misheard it as “Let’s go, Brandon!” The phrase was quickly adopted by right-wing accounts as a coded line of attack, but the Dark Brandon meme co-opted that, and Biden’s campaign—and even the official White House account on X—went on to share it.

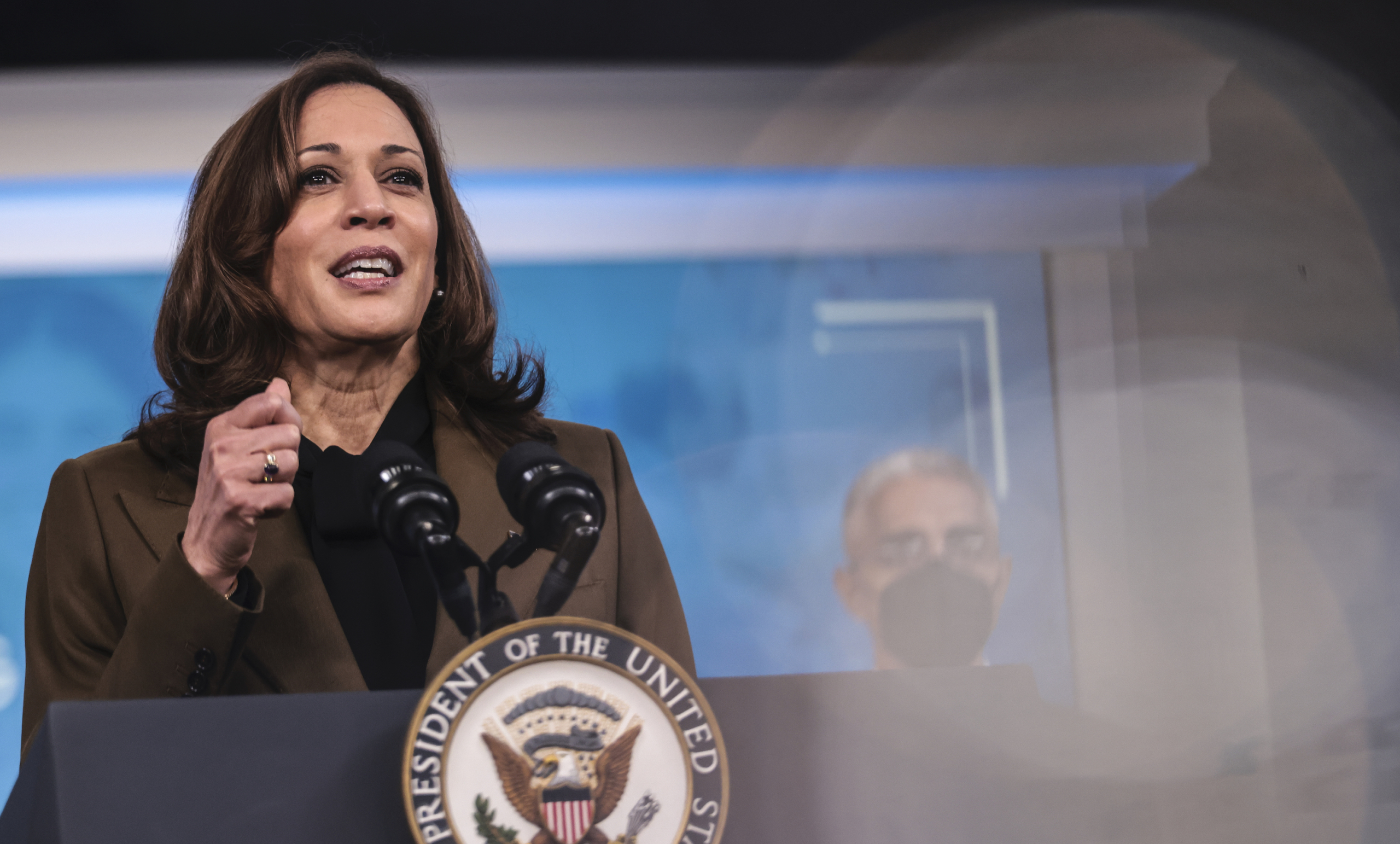

But while these memes got some traction, they didn’t appear to do much for Biden’s following among younger Democrats—at least, not enough to help. Meanwhile—and particularly after Biden bombed in the debate last month—Harris performed more convincingly in this arena, racking up millions of views with a wide range of memes: Coconut emojis. Venn diagrams. The “wheels on the bus” song. “Brat.” The term “coconut-pilled.” Unless you were a connoisseur of Harris content, these terms were likely all but meaningless to you (and may still be). But, within minutes of Biden’s announcement on Sunday that he would not seek reelection, these and other memes started to ramp up and achieve viral distribution on X and other platforms, along with video clips of Harris dancing, laughing uproariously, and pointing at the camera with her sunglasses on—many of them set to the music of Charli XCX, a popular singer and chief exponent of 2024’s “Brat Summer.”

Whether one can win the presidency on memes alone is open to debate, but if such a thing is possible, Harris has a far better chance of doing it than Biden. On the day Biden dropped out, Charlie Warzel wrote in The Atlantic about what he called the Joe Biden Theory of Attention, arguing that “It doesn’t matter what Biden says: After the debate, his brittle demeanor and bizarre slipups became a black hole,” whereby “every bit of attention was locked on his least flattering qualities.” Each public appearance seemed to involve Biden unwittingly creating an attack ad for the Trump campaign, turning Biden into what Warzel called “a self-defeating candidate—able to attract a critical mass of attention, but only in the worst way.” Harris, at least for now, seems to have no such problem; quite the opposite. Even her mistakes have been transformed into posts that make her seem relatable.

Even before Biden’s announcement, according to NBC, X listed “Kamala” among its trending topics in politics with almost two hundred thousand posts; at times “KHive”—the name sometimes given to her more vocal online supporters—made it into the top twenty topics on X. After Biden dropped out, Jared Polis, the governor of Colorado, endorsed Harris for president and added three emojis to his message: a coconut, a tree, and the American flag. EMILY’s List, a PAC dedicated to helping elect Democratic women candidates, also used the coconut and tree emojis; Brian Schatz, the senator for Hawai‘i, posted that he is “ready to help” with a photo of him climbing a real-life coconut tree. Jay Caspian Kang, a New Yorker staff writer, posted on X on Tuesday night that his entire feed was “Kamala pilled.”

For the uninitiated, the term “pilled” is a reference to The Matrix, in which Keanu Reeves’s Neo is given the choice of a red or blue pill, and chooses the former in order to see the truth (rather than the latter, which would allow him to return to blissful ignorance). The “coconut tree” meme is a reference to a speech that Harris gave in 2023, in which she recalled her mother asking her as a child: “You think you just fell out of a coconut tree?” (This, Harris explained, was a reference to the fact that people “exist in the context of all in which you live and what came before you”—a phrase that has itself become fodder for Harris-meme makers.) At the time, some observers mocked the speech as evidence of Harris’s awkwardness, and what some described as her tendency to go off-script in bizarre ways. But in the wake of Biden’s announcement, these and other examples of her distinctive rhetorical style were suddenly repurposed by many social media users in a much more positive way. As the New York Times described it: “If her jocularity—she has an outsize laugh and is known to do impressions—was once mocked, many Democrats now see that quality as a sign of vitality, in contrast to Mr. Biden’s often halting public performances.”

Earlier this month, Taylor Lorenz of the Washington Post compared the trend of Harris’s awkward comments being turned into viral posts portraying her as likable and relatable to the rise of what some have called “meme stocks,” a phrase that refers to shares in publicly traded companies soaring for reasons of virality unrelated to their actual financial performance. The Harris phenomenon is “absurd [and] somewhat ironic,” Lorenz wrote, but has generated “momentum that could have lasting results, boosting her standing among Democratic voters.” Posts featuring generally favorable video edits of Harris have amassed hundreds of thousands of views on TikTok and Instagram, Lorenz wrote. A thread on X compiling such clips—including the time Harris gleefully declared “I love Venn diagrams”—got more than fourteen million views.

Around the same time, Kelly Weill, an author and journalist, wrote on X that “ironic khive posting is unironically the most energized the twitter Dem electorate has been in about a year.” Weill told the Times that the explosion of Harris memes was “almost a pressure release” for progressives who have not been having a great time online of late. The fact that “there is something to joke about, that there is something to rally around, feels like optimistic energy,” Weill said. Bailey Stoltzfus, a law student in Arizona who has posted about Harris on X, told the Post that “she just has these funny relatable moments online,” adding that she is seen as “goofy [and] people characterize her as a wine aunt.”

Harris’s online currency got an even bigger boost this week when Charli XCX posted comments about how “Kamala IS brat,” a reference to her album of the same name. (Charli has described the term as referring to a person who might have “a pack of cigs, a Bic lighter, and a strappy white top with no bra,” or someone who might be “a little messy and likes to party and maybe says some dumb things sometimes.” This type of person, Charli explained, is “very honest, very blunt. A little bit volatile.”) According to the BBC, the tweet got almost nine million views in the four hours after Charli posted it; by Monday morning, Harris’s official account had changed its profile background to match the lime green of the album cover. Harris’s TikTok account also posted a video featuring the song “Femininomenon” by a different singer, Chappell Roan. That had more than twenty million views and four million likes as of Tuesday afternoon.

This might seem similar to Biden’s official accounts co-opting the Dark Brandon meme. But one key difference between Biden’s use of memes and those involving Harris, according to some social media and political analysts, is that the latter seem to be a lot more organic. In order for memes to be successful, they say, a politician can’t be seen as trying too hard to claim them, either by creating memes themselves or by being too quick or too aggressive in adopting them; the best social media assets seem to emerge more spontaneously, adopted first by supporters and only later (if at all) by the candidates themselves. Jules Terpak, a digital strategist and content creator, told the Post that the Harris videos work in part because they are “curated by voters and have an artistic touch that doesn’t go through a chain of command before being sent out.” As one user described it on X, the Biden memes were “a cynical attempt to wield Posting Energy,” whereas the memes around Harris have been “organic, understated, genuinely subversive [and tapped] into the collective Posting Consciousness.”

Phoenix Andrews, a research fellow at the University of Aberdeen and the author of a book on political fandoms, told Business Insider that Harris’s somewhat ironic fandom has been transformed into “genuine warmth.” But genuine warmth has not been the only driver. Numerous posts have compared Harris to Julia Louis-Dreyfus’s character from the TV show Veep, a sitcom about an incompetent vice president who becomes president almost by accident—a comparison that Veep’s showrunner has criticized as being uncharitable to Harris. Jessica Winter wrote in The New Yorker that the memes have also been powered by “irony-poisoned, largely unreconstructed Bernie bros” engaging in “shitposting” (though Winter described this trend as “benign”). Emma Vigeland, who cohosts a talk show called The Majority Report, posted an image of Nicole Kidman celebrating after her divorce from Tom Cruise, with the text: “Me, shedding my toxic Bernie Bro baggage and embracing the warmth of Momala’s embrace beneath the coconut tree.”

Adding to the irony is the fact that some of the most successful memes involving Harris, including those involving her coconut tree speech, were initially created as right-wing attacks against her. In December, the Republican National Committee shared a clip called “Kamala Harris Is ‘Unburdened’ by Competency,” with multiple examples of Harris referring to “what can be, unburdened by what has been”; more recently, this line, too, has been used to portray her as “a likable oddball,” in Lorenz’s words. The Harris account reposted a tweet in which a user told the Trump campaign to stop using the “unburdened” meme because “Gen Z loves it.” Katherine Haenschen, a professor at Northeastern University, told the BBC that “when your opponent says something, you just take it and you make it your thing, and then you’ve taken the power away from them.” Haenschen added that “memes matter [because they are] actually a complex way of conveying information to people.”

How long this love affair will last is anybody’s guess. Lora Kelley noted in The Atlantic that social media infatuation “can curdle fast,” and quoted Caitlin Chin-Rothmann, a fellow at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, who said that Harris’s team should “keep in mind that the ‘extremely online’ population doesn’t necessarily represent the demographics or worldview of the rest of the country.” (If you think it does, I have a celebrity a cappella choir rendition of “Fight Song” to sell you.)

But, as Warzel wrote, presidential elections are to some extent attention contests—”big, dumb spectacles that, at their core, are about the most consequential of issues, but are also sometimes influenced by incredibly superficial concerns from an electorate that doesn’t always vote rationally.” And if memes are the most powerful weapon in that arena, then Harris has a lot more firepower than Biden, and possibly even more than Trump. At least for the moment.

Other notable stories:

- Yesterday, amid protests in Washington, Benjamin Netanyahu, the prime minister of Israel, addressed Congress. (Many Democratic lawmakers skipped the speech. One man who did attend: Elon Musk, the owner of X, who was invited by Netanyahu.) Biden will meet with Netanyahu today; ahead of time, a coalition of media-freedom groups urged Biden to press his counterpart “on the unprecedented number of journalists killed in the Gaza Strip and the near-total ban on international media entering the Strip.” At home, Netanyahu continues to field criticism for his treatment of the press: in a column for Haaretz, Anat Saragusti made the case that Netanyahu is trying to “destroy independent journalism” in Israel. And Arab Reporters for Investigative Journalism reconstructed an Israeli air strike that killed three journalists in Gaza in October.

- Also yesterday, federal prosecutors unsealed terrorism charges against Hadi Matar, the man who stabbed the author Salman Rushdie on stage at a New York arts festival in 2022, blinding him in one eye. Prosecutors alleged that Matar was motivated by the fatwa that Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, then Iran’s supreme leader, issued against Rushdie in 1989, and that Matar believed the fatwa had been endorsed by the leader of Hezbollah, the Lebanese militia and Iran ally. (Matar is a US-Lebanese dual citizen.) He stands accused of committing an act of terrorism in the name of Hezbollah, and of providing “personnel, specifically himself, and services” to the group in the process. (He faces separate charges of attempted murder and assault in New York State.)

- The LA Times is out with a series about the “news crisis” in California, examining how “economic forces and new technology have dramatically reduced local reporting power,” and the state’s “novel efforts” to restore it. Among the contributions, Jessica Garrison reports from Richmond, where the primary local news source is now a publication funded by the oil giant Chevron. Gustavo Arellano writes that the death of Spanish-language newspapers in the state has left a void that gets “filled with trash.” And, with state officials trying to force big tech companies to compensate news outlets, Jenny Jarvie explored the lessons from similar initiatives in Australia and Canada.

- Jim Rutenberg and Jonathan Mahler, of the New York Times, are out with an explosive story, based on sealed court records that they obtained, revealing that Rupert Murdoch is engaged in a secret, Succession-esque legal battle against three of his children over the future of his media empire. Currently, the terms of a family trust dictate that control of the empire will transfer to Murdoch’s four oldest children when he dies—but Murdoch is now trying to change the terms to ensure that Lachlan, his favored heir, will take charge and preserve the empire’s conservative orientation. The other children are fighting back.

- And Lewis H. Lapham, the longtime editor of Harper’s and founder of the eponymous Lapham’s Quarterly, has died. He was eighty-nine. In a remembrance, Harper’s quoted Lapham as saying that what annoys people about the media, “is not its rudeness or its stupidity but its sanctimony.” His life and career “were distinguished by a different approach”—one that aimed “to ask questions, not to provide ready-made answers, to say, in effect, look at this, see how much more beautiful and strange and full of possibility is the world than can be imagined by the mythographers at Time or NBC.”

ICYMI: The media historian Michael Socolow on the limits of history in this moment

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.