Sign up for The Media Today, CJR’s daily newsletter.

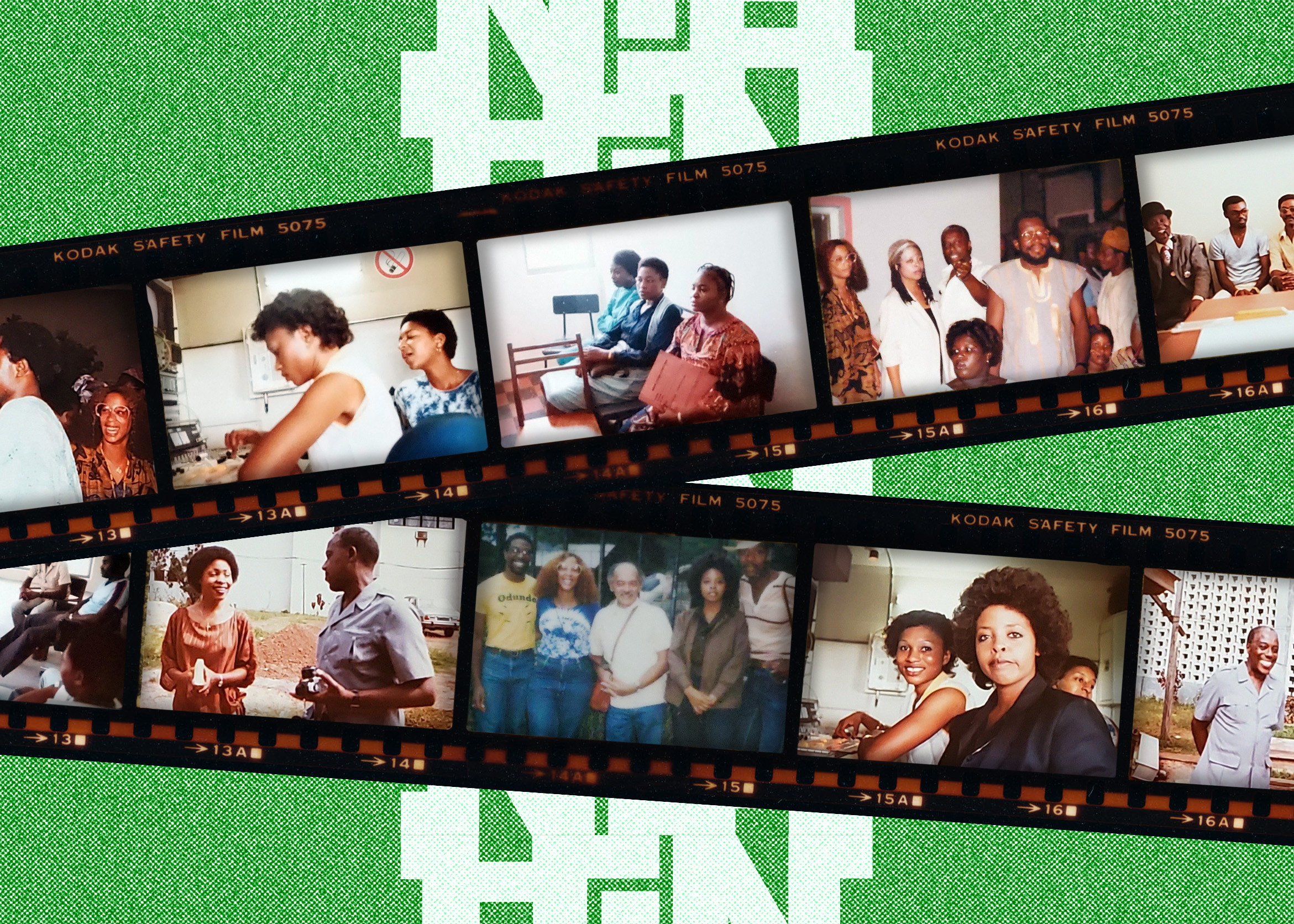

This week, Feven Merid writes about Jacaranda Nigeria Limited, a group of Black journalists who traveled from the United States to Nigeria in the early eighties. Shehu Shagari, the first president of Nigeria to have been elected under an American-style constitution, hired Jacaranda to upgrade the Nigerian Television Authority, the country’s state-owned broadcaster. When the team arrived, they had high hopes of training investigative reporters, improving the NTA’s production value, and building “a premier news service that could effectively push back against Western narratives of Nigeria and Africa as a whole,” Merid writes. The staff of Jacaranda—many of whom had been hired to predominantly white newsrooms after the release of the Kerner Report—were also happy to have found an escape from the persistent racism they’d experienced in their careers back home. But their journey did not go as planned.

I hope you’ll read the piece, which tells a vivid story of the past that feels strikingly relevant today—as American journalism continues its struggle with racism, and Nigerians prepare to head to the polls in a presidential election that could determine the fate of their press. Here, Feven fills us in on some of the background.

BM: How did you learn about the existence of Jacaranda Nigeria Limited?

FM: I learned about it through working on our Beyond Atonement project. I was a fellow at the time. I went through CJR’s archives from the eighties and nineties to write about how we covered race and racism during that time period. I found this article from 1982 about the ways in which Black journalists and media workers in television news, at the big networks—CBS, ABC—and also at their local affiliates, were being marginalized. They were being shut out of opportunities to progress into more senior editorial roles where they could better address the racist practices of TV news. One of the journalists interviewed for the article was a CBS reporter named Randy Daniels. At the very end of the article Daniels briefly recounts how he left CBS and recruited twenty or so Black journalists, producers, directors, and engineers from the big networks to also leave their jobs and go work on television news in Nigeria. It was the last paragraph of the article, and there was nothing else about it—even the name of Daniels’s company wasn’t mentioned. I looked through the archives to see if there was anything that followed up on it, because I wanted to know what ended up happening, but I couldn’t find much of anything on it there or anywhere else. So I decided to report the story myself.

When Jacaranda took flight to Nigeria, it was 1982. The Black journalists who made the trip had chosen to abandon their jobs in predominantly white newsrooms. What did you learn about the context they left behind?

It can sort of be categorized under two things: racist management practices and racist coverage. But of course, one feeds into the other. Black people were not part of the pipeline that led from entry-level roles to more senior positions like producer, editor, news director—the people who had the final say on how to frame and broadcast a story. At CBS, for instance, of the two hundred and sixty-five producers there at the time, only twelve were Black. The numbers were similar at the other major networks. That lack of integration had consequences on how networks covered things and subjected Black employees to a lot of hardship. This was at a time when television news was reaching its height of influence and warping public perception in profoundly harmful ways, in news stories like the Central Park Five case and the video footage of Rodney King being beaten, which exploited Black trauma. Despite the Kerner Report urging integration a little over a decade prior, Black- and Latino-focused news segments were relegated to weekend “ghetto hours”—an industry term at the time. Television’s situation is unique compared to the print and radio press because of TV’s outsize influence on the public’s views and narratives. All the major television networks were exclusively owned by white men and operated at their discretion.

One of the people you spent the most time talking with for this piece was Barbara Lamont, who told you that when she was starting out in journalism, “nobody ever talked to minorities or women on the air.” What was her experience like, as she progressed in her career? What led her to join up with Jacaranda?

Barbara Lamont transitioned from being a jazz singer to a reporter. While she was learning how to be a journalist, and about the industry as a whole, the press was being charged by the government to integrate. So she was forging a career in an industry that had been segregated since its inception and thus hostile to nonwhite people. She produced good work, she ended up writing a book, and she took on more gigs as opportunities arose, eventually moving from local New York stations to network news at CBS. But she was still being shut out in a lot of ways. Her news editors questioned her ability to accurately report on the news because she was Black. She was being paid significantly less. Certain beats, like business news, were completely off limits. Ten years into her career, she was being rejected for jobs that she was qualified for. Meanwhile, she watched her white colleagues be elevated through a pipeline that she was not really a part of. She was navigating all of this as pragmatically as possible. Something she said to me several times when discussing her news career was what her mom would tell her, which was, essentially, “Barbara, if they got a problem with you, it’s their problem, not yours.” She had to keep going, and when Jacaranda came around, she actually didn’t feel as sentimental about it as the other members. Daniels offered her what would be her most senior job yet—and better pay—and so it made a lot of sense for her.

Jacaranda’s mission was to train and upgrade the Nigerian Television Authority, the country’s state-owned national broadcaster. At the start, the group believed they would be mentoring members of the Nigerian press on how to conduct interviews, capture important events on film, and improve the technical quality of newscasts. How did their expectations start to unravel?

Things started to unravel on the newsgathering side. They were training people on what information to collect and from whom, the important things to include in a news story. When that attention would inevitably turn toward government happenings, they faced a lot of pushback in terms of anything that portrayed the government in a bad light. From the beginning, they were not consulting with NTA trainees much on the actual content of the news but how to produce it well. But ultimately for journalists it is impossible to separate the how-to skills of reporting from the content.

In many ways, the members of Jacaranda had as much to learn as their trainees, as they became familiar with Nigeria’s government and its culture. What are some things that surprised the group?

Nigerian culture was new to a majority of the group, and so there was that aspect of cultural exchange. On another level there was sort of a reality check. Many members of the Jacaranda team were in their youth, or young adults, during the civil rights movement in the United States and had experienced how, by the eighties, despite some material gains, much of the momentum had faded away. Nigeria appealed to them in this sense of it being a homecoming to an ancestral land where there would be a shared sense of identity. Some had Pan-African ideals about unity among Black people globally. It was kind of a shock to many when they learned that much of what they believed wasn’t actually the case. The Jacaranda group was acknowledged as American first and foremost; they were even called the word for white (or Europeanized foreigner): oyinbo. It was kind of a crash course in the way that Blackness as an identity in America doesn’t translate to Nigeria, a Black country with a vast range of ethnicities, languages, cultures, and religions. They learned more about Nigeria’s complex relationship to the slave trade and its legacy. They also witnessed firsthand the effects of British colonialism on Nigeria’s development and the political and social circumstances that challenged many Nigerians in their day-to-day lives.

Jacaranda’s project ended with a Nigerian coup. What happened to the country’s press after that?

After the coup, the country’s television press continued to operate exclusively through the government, now under military rule. By the nineties, the government began to open up to some privatization of networks. The print press, which was already a diverse industry in terms of ownership, continued to be an avenue for dissent, but there was repression there as well—it was still a military state. Grace Nwobodo, a former NTA journalist I spoke with, brought up the case of Dele Giwa, a prolific journalist who started Newswatch magazine and was murdered by an explosive that was sent to him by mail. It’s never been determined who was responsible for the mail bomb—but it nonetheless had a chilling effect on the country’s press.

Lamont returned to the United States but did not go back to her career as a journalist. How did she feel about that?

Leaving during the coup was scary and difficult for her. When she returned to the US she was conflicted, disoriented, and she couldn’t really bring herself back to her old work environment. She focused on reconnecting with her husband and daughter. She was able to take her time and figure out her next steps. She applied for an FCC license and eventually opened up her own television station. She credits her time leading the group in Nigeria and receiving good advice from her colleagues that led her to this decision. Lamont felt relieved to exit the editorial side of journalism when she did because she felt the news business, in regards to television and radio, had begun to decline.

For CJR’s Beyond Atonement project, you explored self-conceptions of the press in the eighties and nineties by reviewing archival coverage on race and racism. You described a “diversity fatigue” workshop that took place in 1999, at which a veteran Black journalist began crying: “Over her thirty-year career in journalism, she said, she’d had the same frustrating conversations over and over again. ‘What was the point of all the struggle for integration and understanding?’ she wondered out loud, and left the room.” That was years after the Jacaranda crew left for Nigeria, and it’s been decades since. How would you characterize the nature of today’s conversations in media about integration and understanding? Are we merely repeating ourselves? Is there anything promising that we can build on?

It’s eerie to read about these things from the eighties and then the late nineties and feel like they could’ve been written today, almost word for word. Even going as far back as the late sixties with the Kerner Report, which called explicitly for the integration of newsrooms—that can still be applied to a lot of newsrooms today, especially in terms of more senior positions. These repeated cycles of harm largely come down to disproportionately white leadership and ownership. What has been promising, I think, is the collective organizing of journalists and other media workers to take part in forging better practices and working conditions in this industry. They are raising concerns over dubious coverage and troubling management practices, and they are receiving gainful employment that enables them to sustain themselves in this profession.

I think the efforts that continue to experiment and create alternatives to what already exists will always be worth building upon. The Black press is a historic example of this. Scalawag, Prism, and Capital B come to mind as modern efforts. Capital B, for example, was started by two journalists who left their respective newsroom jobs to figure out a way to report for Black communities on a local level while paying their reporters livable salaries and benefits. All three outlets report from a place that centers marginalized communities. I think it’s also worth mentioning the efforts of worker-owned media like Hell Gate and Defector, as alternatives to the traditional structural and business models that continue to fail our industry.

On February 25, Nigerians are scheduled to vote for their next president. Muhammadu Buhari, who takes power of the country at the end of your piece, is now at the end of his term limit. Leading in the polls is Peter Obi, who represents a relatively small political party—the Labour Party—and who said recently that this is an “existential election” for Nigeria, one of the “most dangerous and difficult countries for journalists” in West Africa. What is at stake for Nigeria’s journalists?

Despite the many changes the country has gone through, the press environment remains a difficult one for journalists. Government interference has persisted through periods of military rule and democracy. There’s a lot of promise in Obi’s presidential bid to upend the political establishment. In part, that could mean a new outlook for the press, including an opportunity to more freely cover politics and corruption.

Other notable stories:

- Jen Psaki, the former White House press secretary, will host a weekly MSNBC talk show starting March 19. “Inside With Jen Psaki” will air Sundays at noon, the New York Times reported, “vying for the same weekend clout as political mainstays like ‘Meet the Press’ and ‘Face the Nation.’” Psaki said that she is neither going to “gratuitously attack” nor “gratuitously applaud” Joe Biden. “If he deserves applause, I will applaud him.”

- A newspaper published by Bangladesh’s main opposition party has stopped printing after receiving a suspension order from the government. The Dainik Dinkal, a Bengali broadsheet, “has been a vital voice of the Bangladesh Nationalist party for more than three decades,” The Guardian reported. “It covers news stories that the mainstream newspapers, most of which are controlled by pro-government businesspeople, rarely do.”

- Jack Mirkinson writes that the Times is making the same mistake with its trans coverage as it did during the AIDS crisis. “The parallels between its current anti-trans coverage and its past coverage of gay rights are obvious,” Mirkinson argues in The Nation. “But the Times appears blind to them—and blind to the fact that, in its obstinance and its arrogance, it is once again placing itself in a situation that it will later regret.”

- And: “Don’t tell a reporter on a date that you’re off the record.” Politico Magazine’s survival guide to DC includes wisdom for journalists and those who wish to avoid seeing their names in print.

Read more: Jacaranda Nigeria Limited

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.