Sign up for The Media Today, CJR’s daily newsletter.

In the early 2010s, a top-secret source inside Danish military intelligence approached a TV journalist in a frosty parking lot and handed her an envelope; inside were photos that appeared to show the CIA illegally rendering Afghan prisoners in orange jumpsuits through an air base in Greenland, an autonomous territory of Denmark. After airing a story, the journalist was visited at home by two sinister-looking men claiming to be police officers, before her apartment was ransacked; she was later charged with disseminating state secrets; in a bid to strengthen her story, she finally persuaded her source to go public, but he dropped out after his superiors threatened to trash his reputation in the press; eventually, he killed himself. The full story didn’t get out—but it did prompt the Danish prime minister to visit Greenland. She would eventually offer policy concessions, but not before a fiery meeting with her Greenlandic counterpart, who raised the thorny history of Danish colonization. “Don’t expect me not to tell you the truth when you are a guest in my house,” he said.

None of this actually happened—it was the plot of an episode of Borgen, a Danish political drama that became an unexpected international hit. Recently, of course, a very real crisis involving the US, Denmark, and Greenland has been in the news: Donald Trump—whose proposal to acquire Greenland during his first term was largely laughed off by an incredulous US news media—has returned to the idea, and this time, far fewer people are laughing. Last month, Trump described Greenland as vital for US national security—among other things, Arctic ice is receding as the planet warms, opening up the region as a theater of great-power competition—and refused to rule out taking it by force. (The country is also rich in mineral reserves, most of which are untapped.) Meanwhile, his son Don Jr. briefly landed in Nuuk, the capital; he was ostensibly there for tourism and to shoot video for a media project, but he also staged a MAGA photo op with free beer and reportedly made some eyebrow-raising remarks, including accusing Danes of racism toward Greenlanders, the majority of whom are Inuit. That made for front-page news in Denmark, even though Greenlanders have been saying the same thing for decades, Angunnguaq Larsen, a local resident, told a reporter from The Guardian—one of many from Western media to have descended on Greenland of late as a global media storm has engulfed the territory. “That’s hypocrisy.”

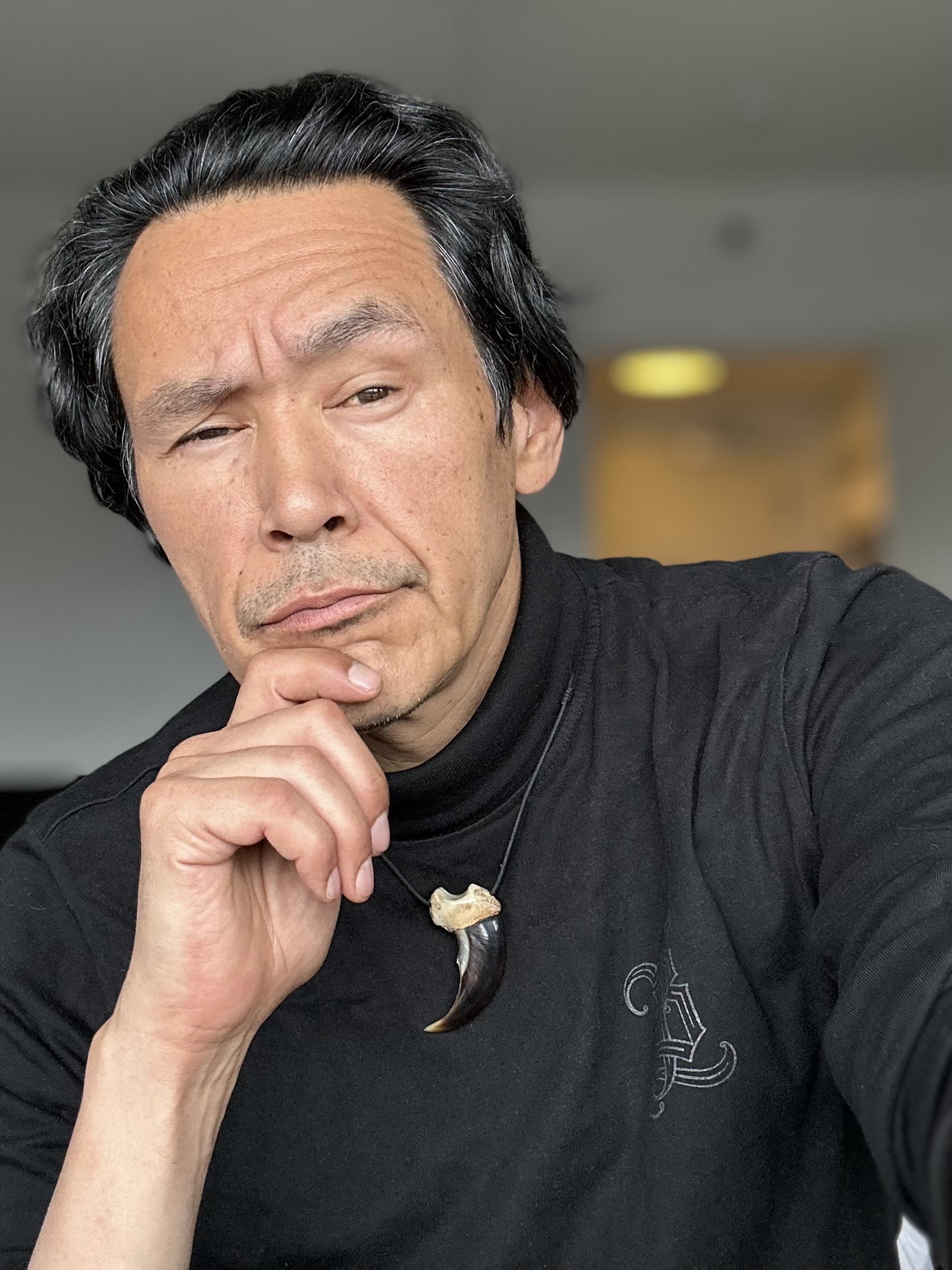

Larsen will be familiar to viewers of Borgen—he played the country’s prime minister in the 2010 episode, and reprised the role when the show returned for a slickly produced fourth season on Netflix in 2022. (His character was by now a lawmaker representing the territory in Denmark’s parliament.) That season revolved around a geopolitical scramble following the discovery of oil in Greenland, with the US, China, and Russia jostling covertly for influence in the territory and Denmark finding itself caught in the middle. If anything, the real-life crisis sparked by Trump has been much stranger. “If I had pitched this as a new season of Borgen, I think most people would say…that I was completely out of my mind and had lost my sense of reality,” Adam Price, the show’s creator, told Reuters last month. In recent days, the story has only grown more absurd. A Republican congressman introduced a bill calling for Greenland to be renamed “Red, White, and Blueland.” A satirical petition in Denmark has called for the country to “Måke Califørnia Great Ægain” by buying the state from the US.

Larsen was born and raised in Nuuk; in addition to acting, he has worked as a musician and sound engineer, and is currently teaching music in a school in Sisimiut, Greenland’s second-largest city. Last week, I called him to discuss life imitating art, but weirder; his views on how the Danish press has covered the crisis; and what advice he would offer his real-life counterpart. Our conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

JA: What was your reaction when you heard Trump starting to talk about Greenland again? Even though he’s said it before, it was not part of his election campaign last year. I think it was a surprise to a lot of people in the US when he started talking about it again after the election…

AL: Trump is quite the opposite of our prime minister, Múte Egede, who is very calm and thinks about his words. With Trump, the words just come out. I was like, Shit, man, we don’t like this man; he should just stay the fuck out of Greenland. That was my initial thought. But in these times, we are also thinking about getting independence from Denmark. Greenland has to be open to cooperation with any country. But it also has to be thought through. We know what Americans did to the Indians and to the slaves; they have a long story of colonialism and slavery. I think some people in Greenland are romanticizing America from the movies. There’s two camps here: the MAGAs and no-MAGAs. The no-MAGAs are saying, Do not let Trump into Greenland. The other side [wants] money from the States to evolve Greenland. So there’s two sides, and they’re quite harsh to each other. It’s hard to listen to them.

You mention that Egede is quite considered with his words, whereas Trump just comes out and says stuff. The episodes of Borgen about Greenland are fictional, of course, but they portray a geopolitical crisis as you would expect it to unfold: everyone talks in diplomatic language, and the significant stuff plays out in the shadows. The way it’s actually playing out now feels stranger than fiction.

Yes. It’s like watching Borgen on steroids.

I saw you quoted in The Guardian. That was one of many pieces I’ve read in major international outlets recently; I know there’s been journalists from all over the world in Greenland since this story blew up again a few weeks ago. What’s that been like? Do people in Greenland find it annoying? Or do they welcome the ability to put their views out into the world?

I was in Nuuk a couple of weeks ago, just days after the bomb exploded. I haven’t seen that many journalists in Nuuk, just walking around with their selfie sticks and their GoPro cameras. We had Russian journalists in Greenland’s press meetings. We’ve never had Russians at press meetings. The interest has been enormous. YouTubers have come in; people handing out dollars in front of stores. I was like, What the fuck is going on?

We’re used to people coming to our land [and] taking our minerals, and they just export it, and get billions and billions out of it. Us Greenlanders don’t. I think there’s a time before Trump and after Trump. [Some people were thanking the Trumps] for making it clearer for other people that there is racism in Denmark against the Inuit. The difference between before Trump and after Trump is I’m talking with you.

Is there anything the international coverage has gotten particularly wrong? I saw that you said it was “hypocrisy” that it took Donald Trump Jr. making a comment about racism against Greenlanders to get it on the front page of Danish papers…

Quite a lot of people from here have criticized the Danish coverage. [Danish outlets have] hired Danish specialists about Greenland, but they’re all quite colored in how they see people in Greenland. There were many factually wrong things in the Danish coverage. It was hard to see. It was quite one-sided.

I saw something on Facebook that I wrote thirteen years ago [about the colonial way of thinking about Greenland]. But nothing happened, nothing happened, nothing happened; then Trump comes and it’s outrageous. We were trying to tell the media, or the people of Denmark, that you are racist against us, but they were like, Shut up, man, just take your grant from Denmark. [Greenland is autonomously governed but receives significant subsidies from Denmark, which has a large say in Greenland’s foreign and security policy.] In their heads we are alcoholics, we don’t work, we abuse our children, stuff like that. They have this stereotypical image of the Greenlander.

What does local media look like in Greenland? How has their coverage been?

It’s still about Trump; he’s on the news every day. [There’s a major newspaper] Sermitsiaq, and KNR [a public broadcaster]. They ask local people what they think about Trump coming to Greenland. Greenlanders are quite informed. It’s a very interesting time for Greenland. I think many people are locked into the news to see, What’s the next move?

You mentioned posting on Facebook. Greenland is a very big place with a very small population [around fifty-seven thousand people]. How does information circulate online? Is misinformation a problem?

Facebook is the way people share the news; it goes fast from East Greenland to North Greenland. I think people are very critical about what comes out; people ask, Is this real? Did you check? I check if something comes out, if it’s fake news. When I can see something is wrong, I write to [the person who shared the link], This is not true, I have to do something about it. We’re not like Americans.

In the latest season of Borgen, which is about the discovery of oil in Greenland, climate change is a huge theme. Clearly, climate change is a very big part of the current story in Greenland as well—but it feels like, in the coverage I’ve read, climate change isn’t a big part of how the story is being told. What is the role of climate change in this story? Could the media do a better job of communicating that?

Everything could be better. The climate change issue in Greenland is for real. It’s quite hard for people outside Greenland to understand how to live in Greenland. Right now, it’s quite cold. But in the summer it can get quite hot, close to twenty degrees [sixty-eight Fahrenheit]. Older people say that the climate now is different from when they were younger. We have to take care about inviting in the American mining industry. We have to be very clear that our nature doesn’t get destroyed.

You played the prime minister of Greenland on TV. Do you have any advice for your real-life counterpart right now? I read an article in The Atlantic suggesting that he seemed to be enjoying the media attention to begin with but now maybe wants it to go away…

I think he does a very good job; I wouldn’t [want to] be in his place, because he has all this responsibility. I mean, it would be fun to sit there, but he’s doing a good job, being very calm and just making sure that people feel safe. My advice for him: just continue being yourself.

Is there anything else you want to say to people in the US or outside of Greenland?

The media [should] come to our cities and talk with locals, see how they respond, instead of going to Denmark and asking experts. We are the experts here. We know our country.

Other notable stories:

- Yesterday, Trump barred an Associated Press reporter from an Oval Office media availability with Elon Musk on the grounds that the outlet’s style guide doesn’t fully reflect Trump’s recent order that the Gulf of Mexico be renamed the Gulf of America; the AP and various advocate groups blasted the move, qualifying it as a flagrant affront to the First Amendment. Inside the room, Musk took reporters’ questions for the first time since he began to gut the federal government; he said that his team is being “maximally transparent,” even though it is, in fact, operating in secrecy. (We also learned yesterday that Musk will file a financial disclosure report to the White House, but that it will not be made public.) Meanwhile, the Washington Examiner reported that Trump’s White House will not publicly release its visitor logs, either.

- The right-wing network Newsmax reported yesterday that Brendan Carr—the new chair of the Federal Communications Commission, who has already opened probes into a number of media companies—is now investigating NBCUniversal and its parent company, Comcast, as part of a broader push to curb diversity, equity, and inclusion initiatives at companies that fall under FCC jurisdiction. Meanwhile, PBS confirmed that it is disbanding its DEI office, and parting ways with the staffers who worked in it, in order to comply with Trump’s anti-DEI orders, though it pledged to continue to reflect “all of America.” It’s unclear whether NPR will follow suit—though it is apparently pushing ahead with a training session on “identity and difference.”

- In other media-jobs news, the Boston Globe’s Aidan Ryan reports on anxiety at a group of newspapers in Maine, where a nonprofit that was seen as a “godsend” when it acquired the titles in 2023 is now weighing whether to implement layoffs. Elsewhere, we noted last week that unionized journalists at New York magazine were threatening to go on strike for the first time ever—but, according to the Hollywood Reporter, that prospect has now been averted after the union reached a tentative deal with bosses on wages and AI protections. And Politico hired Kyle Blaine from CNN to serve as the first “executive producer” of its Playbook newsletter franchise.

- In 2022, Dean Baquet, then the executive editor of the New York Times, directed the paper’s employees to dial back their use of the app then still known as Twitter, for fear that it had become an echo chamber and that “off-the-cuff” posts from staff were hurting the paper’s reputation. (I wrote about the edict at the time.) A new study in the journal Journalism Studies finds, based on an analysis of nearly two hundred thousand tweets, that staff appear to have complied, tweeting less frequently and in less opinionated ways after the order. Nieman Lab’s Joshua Benton has the details.

- And Jonah Peretti, the CEO of BuzzFeed, put out a manifesto against “SNARF”—or the idea that major AI-driven social media platforms incentivize content that prioritizes “Stakes/Novelty/Anger/Retention/Fear”—and said that his company will launch its own social platform, called BF Island, in a bid to create a joyous alternative to the trend. Peretti also said that HuffPost, which BuzzFeed owns, will use “SNARF for good” while maintaining “high journalistic standards.” Last week, HuffPost laid off around a fifth of its newsroom, claiming that the cuts were financially necessary.

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.