Sign up for The Media Today, CJR’s daily newsletter.

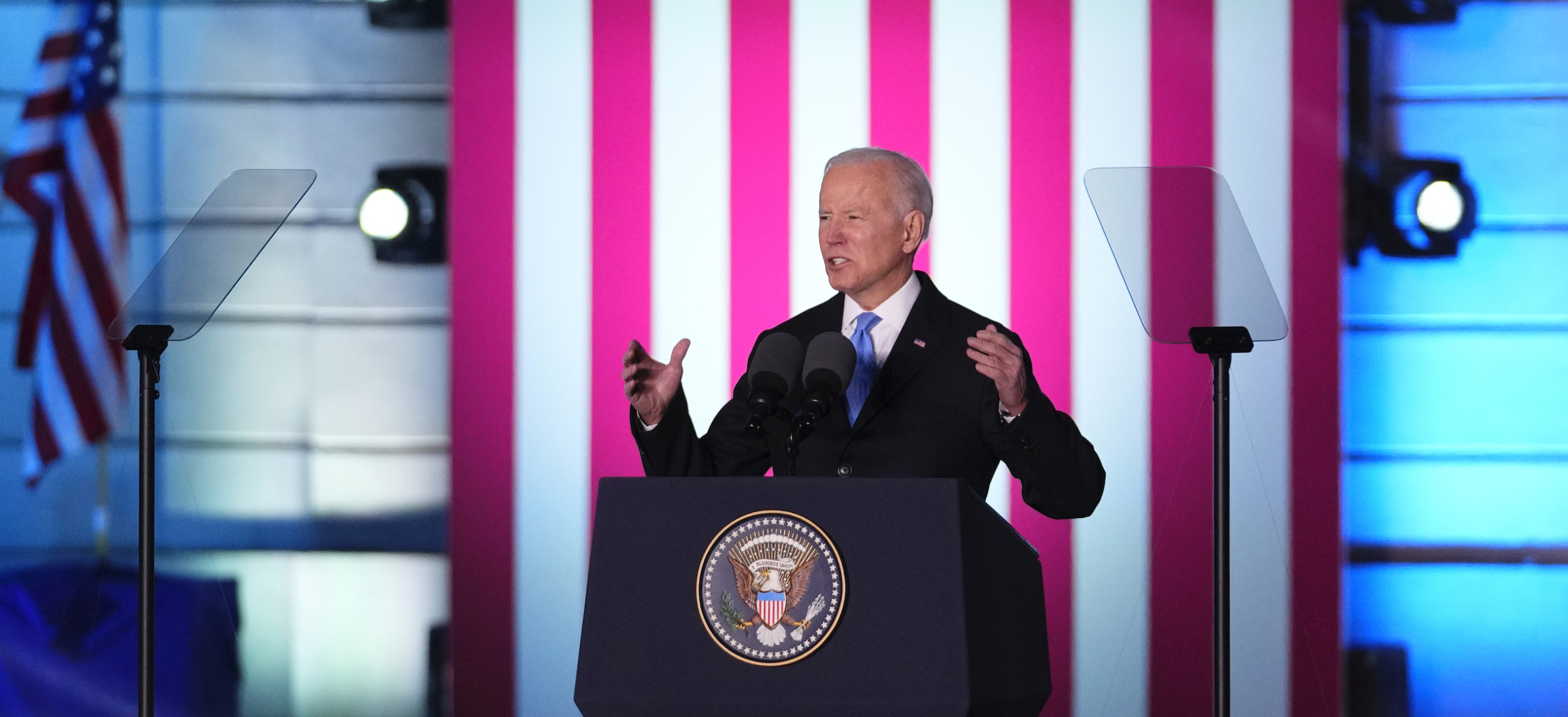

“Nine unscripted words.” Those three words (or similar) were scripted by multiple major news outlets over the weekend to refer to a statement that President Biden made about Vladimir Putin—“For God’s sake, this man cannot remain in power”—at the end of a major speech about Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Biden’s apparent call for regime change has since dominated coverage of his speech despite the insistence of blindsided administration officials—and, as of yesterday, Biden himself—that regime change is not US policy. Another word, one commonly associated with Biden over the years, has recurred in coverage, too: the notion that he had just committed a “gaffe.”

This framing, and the broader media furor around Biden’s apparently off-the-cuff comment, seemed to irk a variety of Biden allies, outside observers, and media critics, who variously argued, among other things, that Biden knew exactly what he was doing (even if some of his aides didn’t like it); that he clearly wasn’t actually advocating regime change as a matter of US policy; that his remarks pale in comparison with Trump’s past “gaffes,” not that the media ever used that word to describe them; that it’s hypocritical for the media to call for Biden to take a tougher stance toward Putin then chide him for doing so; and that the focus on the last nine words overshadowed the highly consequential substance of Biden’s speech, which was about the global battle between democracy and autocracy. Lionel Barber, the former editor of the Financial Times, called for some media “perspective,” characterizing Biden’s remark as a “one-day story” whereas “Putin’s barbaric, unprovoked war against Ukraine goes on and on”; Terrell Jermaine Starr, a high-profile US journalist who is covering the war from the ground, argued that “the only people who give a damn about what Biden said are media snobs who are out of touch with most people who aren’t in their comfortable cafes and aren’t ducking bombs.” Others argued simply that what Biden said about Putin not remaining in power was true. “It was no gaffe. Biden is 100% correct,” Dean Obeidallah wrote in a CNN op-ed. “All I can say in response is: Amen.”

ICYMI: Mali banned two French broadcasters. What does that have to do with Russia’s war in Ukraine?

In the past, I, too, have regularly been annoyed by media coverage of “gaffes,” not least Biden’s. Often, such framing has been telling of a shallow media obsession with what Serious People consider to be smart political strategy—or the “cult of the savvy,” as the media professor Jay Rosen has called it. This worldview makes message discipline a central standard by which politicians ought to be judged, an area in which there does generally seem to be a double standard between coverage of most politicians and Trump, whose comments reliably drive outraged punditry but often get framed as an honest reflection of what he really thinks (despite his many lies). Obsessing over message discipline tends to relegate the substance—true or otherwise—of what has been said to secondary importance, something that we have seen already in coverage of Biden’s stance toward Ukraine. If coverage characterizing Biden’s Putin remark as a “gaffe” instinctively feels trivial, that’s because political media has a history of trivial coverage.

On this particular occasion, however, the line between words and substance strikes me as being a lot more blurry—message discipline in the middle of a war, after all, is a whole lot more consequential than message discipline in a presidential campaign. Even if he meant them, Biden’s words, on their face, were recklessly imprecise, risking the escalation of conflict with a nuclear-armed superpower whose leader is notoriously paranoid. It’s thus hard to see all the focus on Biden’s comments as contrived. The broader, pro-democracy message in his speech was indeed consequential, but this, too, has received media attention, and if the Putin comment overshadowed it, then that’s Biden’s fault more than anyone else’s. Indeed, if Putin’s continued rule is at odds with global democracy, so is one country’s leader appearing to call for regime change in another—especially given America’s history of fomenting regime change overseas.

The problem with the “gaffe” coverage, as I see it, has more been one of contrasts. In recent weeks, commentators from across the media spectrum have criticized coverage of the administration’s generally cautious war policy for being excessively hawkish, with critics often pointing to instances of reporters pressing officials on why they aren’t doing more to stop Russia when the more in question would constitute a dangerous military escalation. The critics have often pointed specifically to questions asked at recent press conferences held by Jen Psaki, the White House press secretary, that were clipped and shared by Ryan Grim, of The Intercept. At one of them, Psaki frustratedly told a reporter that she’d addressed a question about a possible transfer of MiG fighter jets “approximately 167 times.” The reporter replied, “Well, here’s 168.”

Adam Johnson, a progressive writer, called such questions an example of “one of the key features of American journalism: the Faux Adversarial Reporter,” whereby journalists “are able to serve the power centers of our permanent national security state while looking like they’re actually taking on power by grilling an elected leader from the right.” Mehdi Hasan, a host on MSNBC, said he worries that many journalists have a “bias, unwitting even, towards conflict, and combat, and confrontation—escalation,” while only more rarely asking about the prospects for peace. (Grim asked about diplomatic efforts at one of the pressers from which he shared footage, and other reporters have asked about it, too.) Politico’s Jack Shafer wrote that the tone of many of the Psaki questions sounded like advocacy, part of his broader case that journalists “love war.” (“Accusing journalists of loving war is a little like accusing windshield wipers of loving rain,” he clarified.) Writing for the libertarian magazine Reason, Fiona Harrington echoed Johnson: “In the name of balanced national security coverage,” Harrington wrote, journalists are “mercilessly hounding officials who dare to convey the dangers of intervention.”

Since the war began, so many questions have been asked of so many officials that it’s hard to generalize among them; it’s also fair, essential even, to probe the administration’s policies from multiple angles. Nonetheless, in recent weeks, I’ve made similar observations to those cited above, in a manner that is not universal but also clearly goes beyond isolated examples here and there. (I would characterize more overtly bellicose war punditry as a somewhat different phenomenon; I wrote about that recently, and also in the context of the US withdrawal from Afghanistan.) At some point, asking over and over again about no-fly zones, hypothetical “red lines,” and other escalatory measures stops being elucidating, and can, as Shafer notes, start to sound like advocacy for just doing something, even if it isn’t intended that way. If a president must choose his words hyper-carefully in wartime, so must the press.

If reflexive hawkishness is a US mainstream media trend—and I believe that it is, generally speaking, even if it clearly doesn’t apply to every individual journalist—then so is coverage that takes a reflexively adversarial posture toward whatever a given politician is saying in a given moment, in the name of holding power to account. It strikes me that this impulse, too, has affected news coverage of the war so far—which brings me back around, again, to the coverage of Biden’s Putin “gaffe.” While many pundits have agreed with the remark, a good portion of the media furor has been predicated, at least implicitly, on the questionable wisdom of Biden saying something escalatory. Indeed, if his remark hadn’t risked escalation, it wouldn’t have been very newsworthy at all.

The hawkish and adversarial reflexes I mentioned here can coexist across the broad landscape of war coverage. The former is a dangerous form of bias; the latter is fine to the extent that it entails holding our leaders accountable for their words and deeds, but can also be dangerous when the logic guiding scrutiny seems to have no firmer basis than: But what about the opposite of what you just said? This is especially the case in the middle of a war, let alone one started by a nuclear power. It’s legitimate to call Biden’s Putin remark a “gaffe.” But the reason why it’s legitimate should make us think super carefully before asking for the 168th time why Ukraine doesn’t have the MiGs yet.

Below, more on the war:

- What’s “gaffe” in Russian? Predictably, the Kremlin rejected Biden’s comment, though so far, its response has been fairly muted; writing in The Atlantic, Tom Nichols went so far as to say that “the Russians seem to have taken Biden’s remarks more calmly than the American media.” Roughly the same has been true of Russian state media. Jill Dougherty, a Russia expert and former Moscow bureau chief for CNN, noted yesterday that while state media has focused on Biden’s “gaffes,” it has largely played down the regime change question, perhaps because it’s “too hot to handle.” Julia Davis, another analyst, observed that “there are less headlines about Biden’s speech in Russian media than in ours” because Russian propagandists have already “been claiming for years that the US is seeking regime change in Russia and wants to overthrow Putin.”

- More censorship: Yesterday, Volodymyr Zelensky, the president of Ukraine, gave a lengthy interview to four prominent Russian journalists: Ivan Kolpakov, of Meduza; Vladimir Solovyov, of Kommersant; Mikhail Zygar, an independent reporter; and Tikhon Dzyadko, of TV Rain, which the Kremlin recently forced off the air. Russia’s media regulator quickly warned outlets in the country not to republish the interview. “Journalists based outside Russia published it anyway. Those still inside Russia did not,” the New York Times reports. “The episode laid bare the extraordinary, and partly successful, efforts at censorship being undertaken” by Putin’s government, “along with Mr. Zelensky’s attempts to circumvent that censorship and reach the public directly.”

- Meanwhile, in Italy: On Friday, Sergey Razov, the Russian ambassador to Italy, said that he would sue La Stampa, an Italian newspaper, over an article headlined “Ukraine-Russia war: if killing Putin is the only way out.” Razov accused the paper of “soliciting and condoning a crime.” Massimo Giannini, La Stampa’s editor in chief, denied this, arguing, Politico wrote, “that the article only stated that killing the Russian president is emerging—including among governments—as a possible solution to the current crisis,” and noting that “the main thrust of the story was ‘exactly the opposite’ of what Razov said, since it concluded killing Putin would make things even worse.”

- Meanwhile, in California: NPR’s Chloe Veltman profiles Hromada, a tiny Ukrainian-language newspaper that launched in the Bay Area in 2017. “Hromada not only covers the news, but it also promotes fundraisers and protests against Russian aggression,” Veltman notes. Its name “means community, and it provides a way for people over here to stay connected during this difficult time.”

Other notable stories:

- Late last week, a judge threw out a lawsuit in which Felicia Sonmez, a reporter at the Washington Post, had alleged that bosses discriminated against her by barring her from writing stories about sexual assault because she had been too outspoken about her own experience as a survivor. Lawyers for the Post argued that the case should be dismissed on anti-SLAPP grounds, citing a DC law aimed at stopping frivolous lawsuits from impeding speech; the judge rejected this reasoning, stating that decisions about assigning reporters do not constitute speech, but did rule that “a news publication has a constitutionally protected right to adopt and enforce policies intended to protect public trust in its impartiality and objectivity,” and that Sonmez had not made “a plausible claim that the Post took adverse employment actions” against her. She plans to appeal.

- As he prepares to host a new show on CNN+, the CNN streaming service that launches tomorrow, Chris Wallace reflected candidly on his decision to leave Fox News last year in an interview with Michael M. Grynbaum, of the Times. “I’m fine with opinion: conservative opinion, liberal opinion. But when people start to question the truth—Who won the 2020 election? Was Jan. 6 an insurrection?—I found that unsustainable,” Wallace said. “Some people might have drawn the line earlier, or at a different point. I think Fox has changed over the course of the last year and a half. But I can certainly understand where somebody would say, ‘Gee, you were a slow learner, Chris.’”

- Also for the Times, Katherine Rosman profiled Jay Penske, a “quiet Hollywood power broker” whose Penske Media Corporation owns Rolling Stone and Variety, among other publications. “In an industry that rewards attention seekers, he stands apart because of his penchant for privacy,” avoiding red carpet events and social media and declining most interview requests, including Rosman’s. He has nonetheless become “someone to be reckoned with, a mogul who can shape perceptions of Hollywood and its players.”

- Black News Channel, a network that launched in 2020 aiming to be a voice for people of color, shut down after struggling with ratings, workplace turmoil, and its finances. The channel failed to find a buyer and is now filing for bankruptcy; according to Stephen Battaglio, of the LA Times, its closure left more than two hundred staffers, the vast majority of them people of color, out of work. They will not receive severance pay.

- For Vice, Trone Dowd examines efforts by Republican lawmakers in various states to make it more difficult for people to film police officers and publish the footage. The lawmakers said they are aiming “to protect officers’ safety and privacy—not infringe on civilians’ rights,” Dowd reports. “But experts still worry the efforts will be used to crack down on people’s ability to use their cellphones to hold police accountable.”

- Last week, an immigration court judge in Tennessee granted political asylum to Manuel Duran, a reporter who fled his native El Salvador after receiving threats connected to his work and lived in the US for years before being arrested by Immigration and Customs Enforcement in 2018 and spending more than a year behind bars. The Memphis Commercial Appeal has more. (ICYMI, Zainab Sultan profiled Duran for CJR in 2020.)

- Cheng Lei, a Chinese-Australian journalist who worked for the Chinese state broadcaster CGTN, will finally stand trial this week after nineteen months of pretrial detention. Cheng has been accused of supplying state secrets overseas; Australian diplomats have raised concerns about her treatment and asked to attend her trial, though Australia’s ABC News reports that this request is unlikely to be granted.

- In 2018, Charlie Elphicke, then a lawmaker in Britain’s Parliament, sued the Sunday Times after the paper reported on a rape allegation against him. Elphicke used British libel law to persist with his suit even after a court convicted him on sexual-assault charges, but he dropped it recently, allowing the Sunday Times to finally tell the story in full. The paper noted that the episode “shows a free press does not come cheap.”

- And, as you will undoubtedly have seen already, Will Smith smacked Chris Rock onstage at the Oscars last night. According to IndieWire’s Chris Lindahl, the Academy tried to “quash” reporters’ questions about the smack even as it “gripped the attention of the press corps, which struggled to compose itself after the incident and was frequently distracted by its fallout even while other winners were in the interview room.”

ICYMI: BuzzFeed and the demands of being public

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.