Sign up for the daily CJR newsletter.

It is winter in New Orleans, and my mother is dying. As I sit at her bedside, on the verge of being overcome with grief, I try to distract myself with work. I’ve been asked to write about the great Pulitzer Prize-winning photographer John H. White: his pictures, his legacy, and his famously unique spirit.

My mother has dementia. She and I are alone, except for her cat curled up asleep at her side. But thinking about John White makes me feel like I have company. In this dark moment, my memories of him, like the images he captured with his camera, feel like a gift.

I remember the night he touched my life. The Eddie Adams Workshop is an institution in the world of photojournalism: four days for professionals and students to meet, learn, and bond. John White, with his perfect Afro framing his ageless face and smiling eyes, has always been involved, or at least in my fading memory he always has been.

I was first invited to the workshop in the 1990s, when images were made on film and digital cameras were slightly smaller than a Smart car. At the time, I was an eager 20-something photo intern at the Los Angeles Times. John White was there, as was Gordon Parks, the legendary black photographer and filmmaker, both in the role of professional instructors. I was one of 100 young photographers hoping to learn from them.

A crowd of 10,000 cheers Elijah Muhammad at his annual Savior’s Day Message in Chicago, 1974.

I recall other young photographers of color, but as far as I can remember, I was the only black participant apart from faculty members like White and Parks. Even then, this was becoming a familiar experience. I’d find myself thinking: I must do more. I must be the best.

White, of course, came up in an even less diverse era. A preacher’s son from Lexington, North Carolina, he was born in 1945, when the idea of a black photojournalist barely existed. A teacher once told him he’d grow up to be a garbage man. As the story goes, White’s father told him it was fine to be a garbage man “as long as he was the one driving the truck.” He was taught to work hard and take pride in that work, whatever it was.

There was such violence, fear, and crime, but the exposure of images became a light that only photography could create.”

I’d heard of White before the Eddie Adams workshop. I knew he worked for the Chicago Sun-Times, where he’d won the Pulitzer for feature photography in 1982. I also knew he’d won his Prize for a collection of pictures taken over the course of a year, a rarity among photographers, who are usually honored for a single image or a photo essay or story, which involve a collection of related images. Indeed, John White is the only photojournalist in the last 100 years who has won a Pulitzer in either of the photography categories with a portfolio of one year’s work. He is also one of only six black photojournalists who have won individual Prizes.

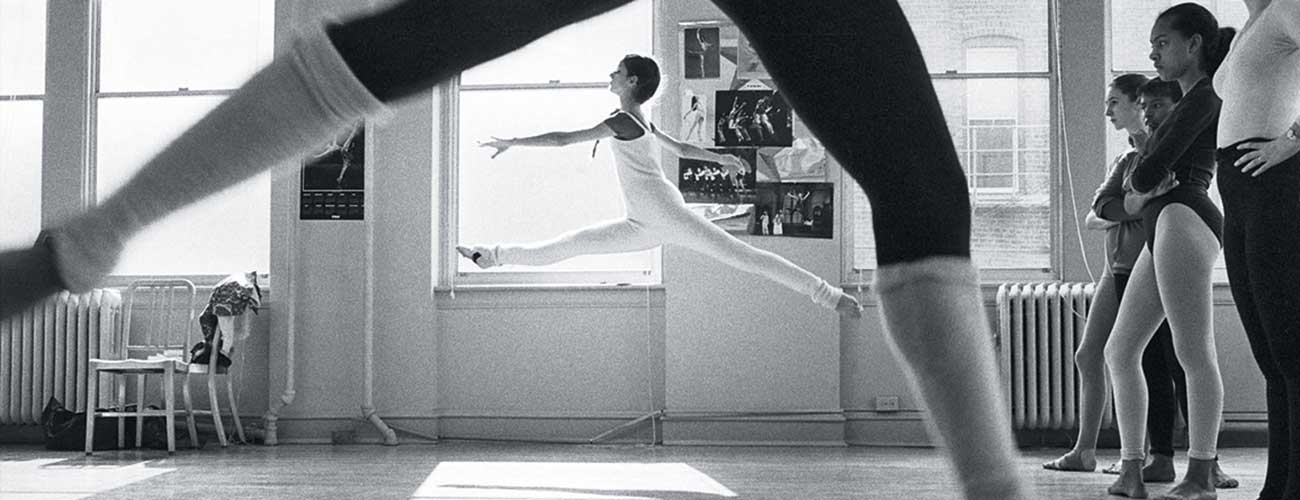

White’s winning portfolio captures his powerful and consistent vision: simple, straightforward images; beautiful use of light; muscular composition; and subversive, meaningful moments. It contains images of daily life in Chicago, from the whimsical—a dinosaur skeleton having its teeth brushed and a penguin frolicking—to a touching and sweet image of two little girls playing a single violin. Young ballerinas leap and float. A National Guard citizen-soldier trains hard. A child plays in a dilapidated hallway at the notorious Cabrini-Green public housing complex.

Girls play in the flow of a fire hydrant in the Woodlawn Community on Chicago’s South Side, 1973.

One cold autumn night, on a bus back to the Eddie Adams farm after a trip to town, I spied an empty seat next to White and grabbed it. We quickly fell into a hushed, intimate conversation, and he asked me a question I’ll never forget: “Are you a black photographer or a photographer who happens to be black?”

I remember tears welling in my eyes, and hoping that he couldn’t tell. Even back then, it was a question I asked myself often, an exercise in the emotional complexity of being black in America. I don’t recall what I said, or whether I said anything at all.

White’s question reminded me of the “double-consciousness” that W. E. B. Du Bois describes in The Souls of Black Folk. Being black in America, Du Bois writes, means living with a “sense of always looking at one’s self through the eyes of others, of measuring one’s soul by the tape of a world that looks on in amused contempt and pity. One ever feels his two-ness—an American, a Negro; two souls, two thoughts, two unreconciled strivings; two warring ideals in one dark body, whose dogged strength alone keeps it from being torn asunder.”

When I was an intern at the Times, there was only one black photographer on staff and a few photo editors of color. I sometimes felt that my race was more important than my skills. Shortly after I started there, a white reporter asked me to work with her on a story involving black teenagers in south LA. I gladly agreed and shared some of my ideas, but she told me she wasn’t looking for ideas. I want you to come with me because I know you’ll be able to calm these kids down, she said, more or less. So I went along and calmed the kids down so that she could talk to them. I made a couple decent frames, but on that story, my dreadlocks and persona were what mattered.

Abandoned housing pockmarks Chicago’s South Side; buildings are left vacant after fires, vandalism, or owners’ failure to provide basic services, 1973.

Is John White a black photographer or a photographer who happens to be black? The answer is complicated. I can only imagine looking at a newspaper today and experiencing as powerful a body of work as White’s, with an earnest visual stream of consciousness that is tightly edited and that explores a city and its people through various moods that span what it means to be alive. As then-Sun-Times Executive Vice President and Editor Ralph Otwell wrote in his 1982 letter accompanying White’s Pulitzer portfolio, his work was “as big as life itself.”

In one of White’s pictures, we travel beneath Chicago and walk the line with a worker in a subway tunnel, in awe at what men and women have created to move us to and fro. His photograph of a preemie struggling to live forces me to stare, silently offer a prayer of thanks, and then smile as I think about my little Papi at day care.

We go to jail and watch a nun minister to a captive flock. I think and feel. Those of us who believe in a higher power sense the presence of God within the picture of a baptism in the churning waters of Lake Michigan. I continue to feel.

This is life. John White reminds us that we are alive.

But there’s something else in these pictures, too, something troubling. We take a journey through the gritty, graffiti-covered world of Cabrini-Green. We feel the pressure of poverty; the history of redlining in Chicago is evident, the plight of black folk clear. Though we don’t see gangs, we feel their presence. We walk the beat with cops, and feel the intensity of their assignment, as well as concern for the young people they arrest. Yet even here, the strength of the spirit cannot be denied. Amid the poverty, there is pride—even joy.

“Photography took the handcuffs off of that place,” White told me recently. “The children could smile again, play again because of the power of journalism. There was such violence, fear, and crime, but the exposure of images became a light that only photography could create.”

One of these photos has become iconic. It captures children smiling and playing in front of a monolithic tower at Cabrini-Green. Though the building looms over him, the boy at the center of the frame is larger than life. His joy is infectious, impossible to ignore. Young black men are often viewed as threats, but this boy is palpably innocent. White chose to celebrate a black child. I believe this was an artistic decision, not a political one, but it carries a deeper social meaning.

I imagine White must have felt an added responsibility as a black photographer in Cabrini. Not to right a wrong, but to do right by the people he was photographing, as opposed to just making a good picture. In my own life, it’s moments like these when I’ve felt like a black photographer, rather than a photographer who happens to be black. You look at this world with a historical perspective, and try to give a voice to the voiceless. It’s not just an assignment or a job. It’s a sacred responsibility.

It hurts to admit that John White’s Pulitzer is much larger than the pictures for which he won. It cannot be separated from the social implications of his being black, in a field where concerns about the lack of diversity are as pressing now as ever. Take the city I call home, New Orleans, which is more than 60 percent black, with a growing Latino community and a substantial Asian population. Yet the photo staffs of our mainstream newspapers and wire services do not begin to reflect the community’s diversity.

John White didn’t dwell on the negative. When the Sun-Times laid him off in 2013, along with the rest of its photo staff, he responded with grace. “I light candles, I don’t curse the darkness,” he told The New York Times. “Even now, my colleagues are cursing the darkness. I’m lighting the candles. And I give wings to dreams, I ain’t breaking no wings. I’m not clipping any wings. Make a difference in the world. One light. One day. One image.”

My mother died on a Saturday in January. It was automatic to think of White as I mourned her. He is a deeply spiritual man, and something I read recently has taken me deeper into my meditation on his importance in my life.

“I believe in God, who made of one blood all nations that on earth do dwell,” Du Bois wrote in his essay “Credo.” “I believe that all men, black and brown and white, are brothers, varying through time and opportunity, in form and gift and feature, but differing in no essential particular, and alike in soul and the possibility of infinite development.”

Am I a black photographer or a photographer who happens to be black? I can answer White’s question now. Within my double-consciousness, I am both.

In 1997, the Los Angeles Times assigned photographer Clarence Williams to document the lives of children growing up with drug-addicted parents. Williams spent days and nights with addicts and their kids, capturing images of a mother shooting up heroin near her 3-year-old daughter and the son of a speed addict digging through a dumpster for clothes.

An image from Williams’s Pulitzer-winning series.

One afternoon, Williams was hanging out with a female speed addict. She liked to get high and clean frenetically, “like a crazy person,” Williams recalls. In a drug-induced fugue, she deposited her infant daughter on a blanket on the floor and started vacuuming. Through his camera lens, Williams saw the baby grab for the vacuum cleaner cord and bring it to her mouth. “I had no desire to take a picture of a child electrocuting herself,” he says. He put down his camera and picked up the baby. “I believe there are times when we’re in the world and we have a journalist’s hat on, and there are times when you have to take the journalist’s hat off and put on your human hat. That was a time when I had to put on my human hat.”

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.