Sign up for The Media Today, CJR’s daily newsletter.

If you were seeking a visual metaphor to use in a cartoon about how Pat Oliphant sought out the 1967 Pulitzer for editorial cartooning, the image of him bending over to offer a view of his derriere to the Pulitzer Board would work nicely.

As he tells it, he wanted to make a point about how the Pulitzer Board’s choices in the cartoon category were more about personal politics than identifying exemplary work in this field.

Oliphant looked back at previous winners of the editorial cartooning prize and, based on that, chose from his work a submission he thought would suit the judge’s tastes and the prevailing political opinion at the time. He says now it was “one of the worst cartoons I’ve ever drawn.” It depicted the president of North Vietnam, Ho Chi Minh, holding a dead Vietnamese with the caption “They won’t get us to the conference table . . . will they?” Well, guess what? That cartoon did in fact win. (Back then it was common to award a single cartoon rather than a body of work.) Oliphant’s response to his prize was to never again enter his work and to use his status as a past winner to criticize the Pulitzer selection process well into the future.

Oliphant considered his Pulitzer-winning cartoon—submitted in an act of irreverence—“one of the worst cartoons I’ve ever drawn.”

Editorial cartoonists are often described as irreverent in their treatment of unscrupulous politicians and institutions. Oliphant was only doing what an editorial cartoonist is supposed to do—provoke, challenge, irritate, and simply piss people off in order to expose the untruths and inequities that everyone else accepts. The only difference on this occasion was that Oliphant aimed his pen at the institution that happens to award the highest honor in editorial cartooning and, for that matter, all of professional journalism.

Whatever you think of his antics, Pat Oliphant is deserving of pretty much every award you could throw at him, because of the brilliance of his concepts, of course, but also the artistry of the cartoons themselves. I know many people will argue, with validity, that the idea is much more important than the drawing. Fortunately, we don’t have to make that choice with an Oliphant cartoon. He excels at both. He instinctively knows that this is a visual medium, and when an editorial cartoon also has a strong, well-drawn image, it will pull in readers at a speed words never could. When you combine that kind of visual with a killer message, I guarantee you the cartoon will be the most potent piece on the opinion page, the element that challenges the conventional wisdom.

Pat Oliphant was born in Adelaide, Australia, where he began his newspaper career, first as a copyboy for The Adelaide News and then doing graphics for a competing paper called The Adelaide Advertiser. Before long, he was promoted to the position of editorial cartoonist. After touring the world to study cartooning, he decided in 1964 to move to the United States.

In a 2014 interview with The Atlantic, Oliphant explained what made him leave home. “I came from Australia, a country where nothing happens. Here, the place was polarized, as it tends to be all the time. And this is a happy hunting ground for cartoonists, if you’re that minded.” He first worked for The Denver Post and then, in 1975, for The Washington Star. When the Star folded, Oliphant continued to work independently while his cartoons were syndicated worldwide by Universal Press. His cartoons, paintings, and sculptures have been exhibited at the Library of Congress, the Smithsonian Institution’s National Portrait Gallery, and many other institutions throughout the US and overseas.

I became aware of Oliphant’s work years before I ever considered becoming an editorial cartoonist myself. I was studying character animation in the early 1980s at California Institute of the Arts and had no particular interest in politics, so I followed Oliphant’s work purely for the quality of his draftsmanship. While in art school and working in the animation industry for companies like Disney and various feature film houses, I scanned the newspapers for his latest creations. I marveled at his drawings of big Soviet bears and surly old men in black suits. His depictions of decrepit, lecherous Catholic priests and sadistic nuns were wonderfully irreverent, and more than once he was attacked for his commentary on the Church’s sexual abuse scandals. “The Annual Running of the Altar Boys” is an editorial cartooning classic. His drawings of chaotic battlegrounds and scenes of destruction seemed so detailed, yet upon close inspection the lines were loose and spontaneous.

As art students, we were taught that a successful drawing must be built on a firm foundation—all the shading and pretty details were superfluous if the drawing underneath wasn’t solid. We were required to take basic art classes—color and design, perspective, and figure drawing—for two years, and just one actual animation class per semester. Those foundational classes are where I truly learned to draw, and they still influence my work today. So I have a deep appreciation for the mastery within an Oliphant drawing. In geeky cartoonist terms, his drawings were so solid you could stomp on one, jump up and down, and it wouldn’t crumble.

Oliphant’s artwork evolved over the years. His earlier cartoons, up until the Nixon and Ford era, were more cartoony than his work today, employing the bigger heads and smaller bodies that most cartoonists favored back then. There is nothing wrong with this style, but his early work didn’t come close to the level his drawing later reached. His next phase began in 1988, when Oliphant was asked by William Christenberry to speak to his class at the Corcoran in Washington, DC. Oliphant enjoyed the artistic environment so much that he returned twice a week for several years to attend figure drawings sessions. In art, there is no better way to develop one’s drawing skills than to understand and to practice sketching the human figure. Oliphant recognized that and began an academic’s devotion to knowledge.

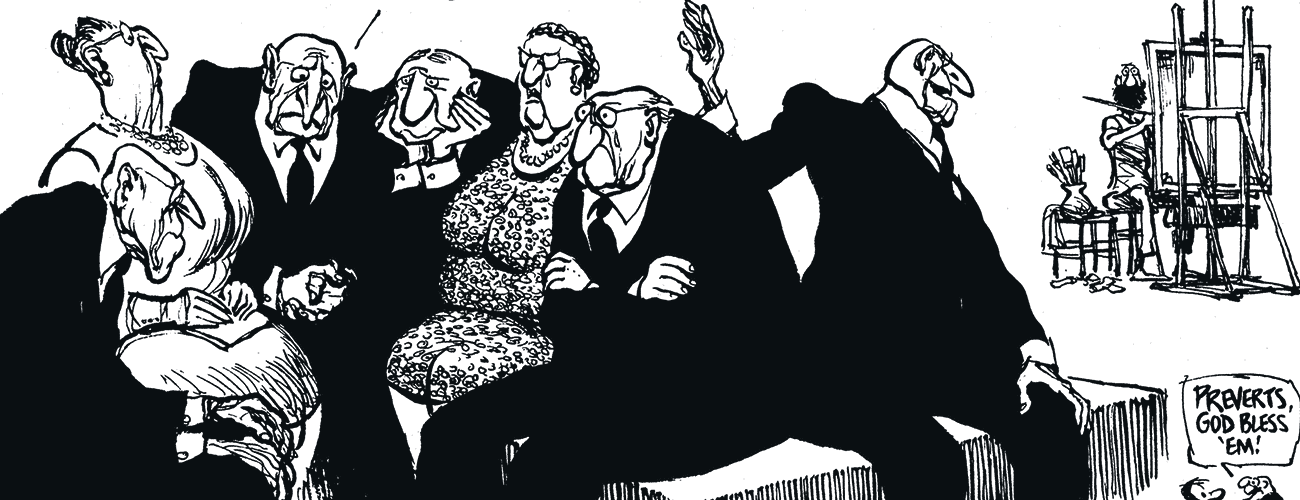

Oliphant developed a great sense of composition, and he mastered the balance of positive and negative spaces. A cartoon from 1990 about the conservative movement to defund the National Endowment for the Arts illustrates his draftsmanship through his use of solid black shapes. There are no lines indicating folds in their clothes, yet the cartoon reads perfectly as a group of men in black suits. In the hands of a lesser cartoonist, the image would look like a black blob. Oliphant’s drawing has visual depth and strength. It works.

Among the ways you can measure Oliphant’s legacy is by the number of cartoonists who have absorbed his work into their own. As with the late, great editorial cartoonist Jeff MacNelly, whose devotees have spawned the term “MacNelly clones,” there have been Oliphant imitators in the editorial cartooning profession. I’m sure some of my earlier work shows painful attempts at imitating an Oliphant-esque drawing. It all comes back to his level of draftsmanship, only that’s not something one can easily copy. As most of my colleagues would agree, there are few whose artwork comes close to Pat Oliphant’s.

So if there’s any regret on behalf of the Pulitzers in granting Pat Oliphant the award, albeit for a bad cartoon, there shouldn’t be. Consider his scheme to hoodwink the judges proof that he possesses the cheekiness that animates every great cartoonist. Consider his body of work both for his razor-sharp observations and his artistry. Taunted or not, they made the right call.

Ann Telnaes was working for Walt Disney Imagineering one day when she saw a young woman named Anita Hill being grilled on television by a line of senators fanned out in front of her. That is Telnaes’ first firm memory of what triggered her pivot from animating cartoon characters in Los Angeles to animating the political characters of Washington.

Before long, she was sending her portfolio to editorial page editors who might be looking for fresh ideas. What Telnaes had that few others did was a woman’s perspective, something still rare in the province of editorial cartooning. Today, Telnaes is only the second woman to ever win the Pulitzer Prize for editorial cartooning. Why so few women? “I believe there are more male cartoonists because there are more male editors, and people tend to hire people they’re comfortable with,” says Telnaes. “Like any other business, people mimic what they see.”

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.