Sign up for The Media Today, CJR’s daily newsletter.

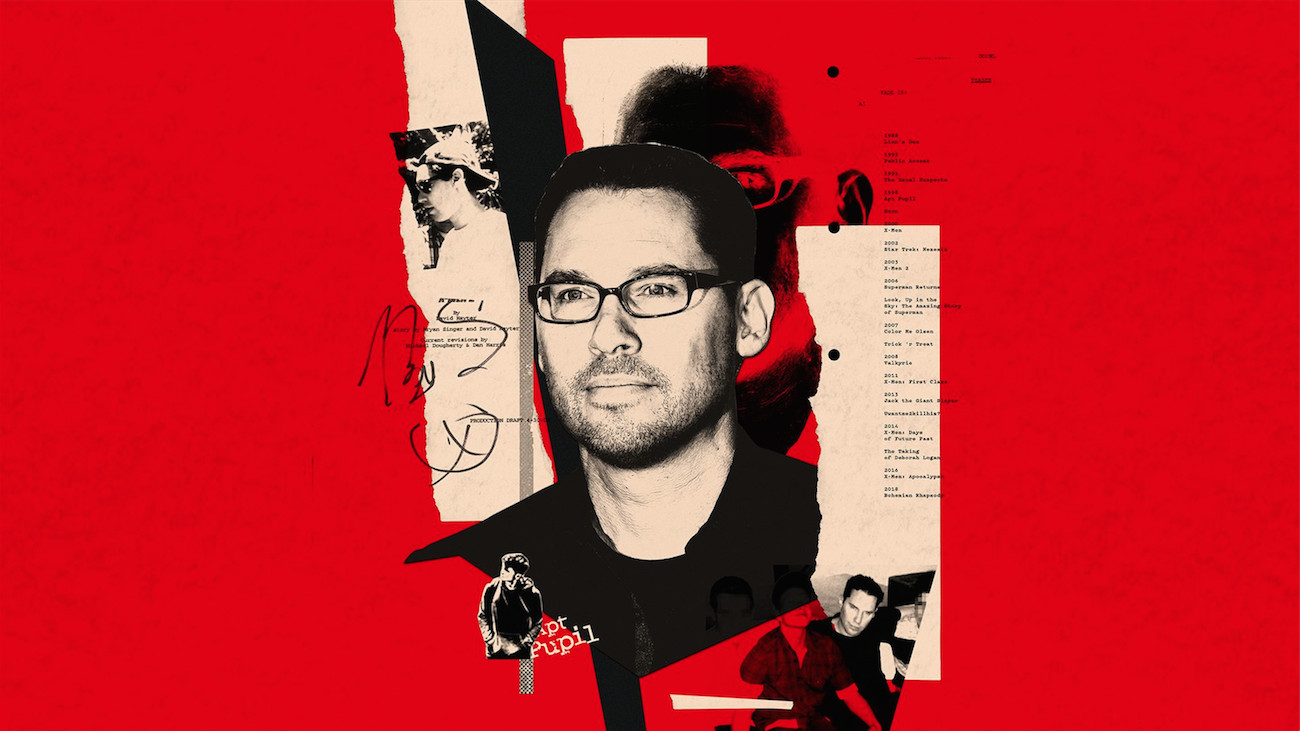

On February 11, news broke that Millennium Films was delaying Bryan Singer’s Red Sonja, which was to begin production this year. This was, on the face of it, a remarkable turn of events. Singer’s Queen biopic, Bohemian Rhapsody, had just been nominated for five Oscars. It performed exceedingly well at the box office, as is usually the case with Singer’s movies; all told, they’ve grossed more than a billion dollars.

Yet halting Red Sonja came as the result of an extraordinary revelation: in late January, The Atlantic had published a story by Alex French and Maximillian Potter, unearthing allegations of predatory behavior against Singer, who had already been subject to sexual assault lawsuits in 2014 and 2017. French and Potter quoted a man who said Singer fondled his genitals during the production of 1998’s Apt Pupil, when the accuser was 13 years old.

While journalists reading the story were as riveted by the disclosures as anybody else, they also had an insider-media question: Why had the story run in The Atlantic at all? French and Potter are on the masthead of Esquire—French is a writer at large, Potter is the editor at large—leaving many to question why that magazine had taken a pass. In a joint statement, they said that, in fact, the story had originally been Esquire’s. It had even gone through fact checking and legal vetting by Hearst, Esquire’s publisher. But Hearst executives killed the story, French and Potter said, and they weren’t told why. (Hearst executives didn’t respond to repeated requests for comment. Jay Fielden, Esquire’s editor in chief, declined to comment.)

ICYMI: Reporter behind controversial BuzzFeed scoop speaks

Recently, I spoke to French and Potter about the genesis of their story, their months of reporting, and the back story behind Hearst’s decision not to publish. “Here’s what I can say,” Potter told me. “I genuinely, wholeheartedly believe, if I got hit by a bus tomorrow, and had to talk to the Big Guy, and he asked me, ‘Hey, do you know why they killed this piece?,’ I’d say, ‘No.’”

The story began in late 2017, when Michael Hainey, Esquire’s editorial director, assigned Potter and French to dig into rumors about pedophiles in Hollywood. Shortly afterward, the two began reporting, and soon after that, they began hearing about Bryan Singer.

THE MOMMIES

Potter: We did our first of many trips to LA, and around the country, on January 16, 2018. Alex and I rented an Airbnb in Venice Beach for a little over a week.

We start reporting on this initial subject matter. Many of our sources are mentioning Bryan Singer, and his connections—or perceived connections—to what we’re reporting. We end up coming upon sources that Alex lovingly dubbed The Mommies.

French: Paula Dorn and Anne Henry were school teachers who had been stage moms. In the early 2000s, their kids were navigating Hollywood, trying to book gigs. They started a non-profit whose mission was educating parents on the business realities of having your kids work in Hollywood: how do agents work, how do guilds work. It’s stuff nobody ever teaches you.

In 2003, one of them was on eBay, and started seeing these headshots of kids they knew, on sale for 50 bucks a pop. They started digging around, and noticed all the buyers and sellers were connected. They found this message board called Boys On Your Screen. The threads ranged from boy actor birthday wishes to discussions about which kids were sprouting pit hair. In that moment, their mission flipped. They went from talking to parents about show business to tracking pedophiles in Hollywood.

Potter: They laid out what they believed to be a matrix of affiliated and loosely affiliated pedophiles and alleged pedophiles in Hollywood. And they had Bryan as a critical cog in the wheel of the machinery. They even had a diagram.

I walked out of there thinking, based upon what they laid out, they were cuckoo for cocoa puffs.

French: Maybe this is why our relationship works, because I had the exact opposite reaction. I felt like, if even a portion of what they were saying was true, then Oh, my God. They were talking about some of these convicted pedophiles used big LA acting and modeling conventions as recruiting grounds. They talked at some length about Digital Entertainment Network, aka DEN.

DEN

Potter: After The Mommies, we were very interested in DEN. I said to Alex, “Wait a minute. I think this DEN thing is what I was hearing about 20 years ago in LA [when Potter worked at a film magazine, Premiere] that I dismissed as fantastical horse shit.”

French: Two things happen. On the last day of the trip, Max turned up this lawyer in Encino who says he represented somebody—he wouldn’t say who—in some litigation related to DEN. So we called the lawyer, who says he’ll help us out. We get in the car. I’m driving. Max puts in his headphones, and calls up another source as we’re driving through Topanga Canyon.

Potter: One of my early stories for Premiere was a front-of-the-book dispatch from a movie set. They would send some knucklehead reporter to the set of a movie for a couple days, and you would find some kisses and cupcakes story about how the movie was getting made. You’d write it, then Premiere would sit on it until the release of the movie.

They sent me to the set of Apt Pupil. I spent two or three days there. Shortly thereafter, a handful of minors end up filing civil complaints against Singer and other producers and production entities as co-defendants, alleging they were, in layman’s terms, bullied into stripping and felt uncomfortable, and sexually harassed.

That was pretty big news. So there I am. I’m supposed to do this kisses and cupcakes story when it became a different sort of a piece. It became something of a curtain raiser on what appeared to be a civil litigation moving into court or settlement of some kind.

When I wrote that piece, it was moving toward something, and that was it. I never knew what happened. Now we’re in the car 20-plus years later, we’ve left The Mommies, we’re on the way to an attorney in Encino, and I say to Alex, “You know what? I don’t know what the fuck happened to those lawsuits.”

So I call up someone who was connected to the plaintiffs in the Apt suit. I say, “Hey, whatever happened to those lawsuits?” He says, “Well, I can’t go into detail on it, because of NDAs, but there was a global settlement.” I was like, “Wait, what?” I tried to get him to tell me how much it was for, and he wouldn’t tell me.

Then we get to the office of the attorney in Encino, who was connected to various lawsuits filed against DEN, and he knew some of the defendants: Brock Pierce, Chad Shackley, and Marc Collins-Rector, and he knew some of the plaintiffs. We’re now in DEN-land; we’re trying to make sense of what DEN is and was. Was Singer a part of it, like The Mommies had told us, or not? How much of it is fact or fiction? We were educating ourselves, and it seemed really fucking shady. We didn’t know, at that point, if the story was DEN, Bryan Singer, or the original entity.

Reporter Maximillian Potter. Photo by Jeff Panis.

BACK HOME

Potter: Alex lives in Jersey. I live in Denver. For more than a year, we would have three to 20 phone calls a day. From the moment we got the assignment, we were in constant communication. We became one another’s closest confidants in life.

When we were back home, we pursued another thread from LA. A civil suit has been filed against Bryan by Cesar Sanchez-Guzman, who claimed Bryan raped him on a boat when he was 17. We asked ourselves, “Who’s Cesar Sanchez-Guzman?” We reach out to his attorney of record, Jeff Herman, and we start to begin to develop a rapport with him.

French: While that was going on, it can’t be understated how big #MeToo was in this moment, what a powerful force it was, culturally. Being so far away from Hollywood, Max and I felt that was going to play to our advantage. We assumed we’d be able to call some publicist or some manager, and say, “Hey, we’re reporting around this subject area,” and if people knew things, they would tell us…And that was just not what happened.

We would have a manager say, “Oh, I can give you this on background from so-and-so, but he or she doesn’t want his or her name attached to it.” Or: “There’s one person you might want to speak to,” and then that person wouldn’t want to talk. #MeToo seemed to us, throughout the process, this construct created by media people on the East Coast.

Potter: As we were learning [from the stories about Harvey Weinstein], several of the female victims, alleged and otherwise, who had come forward, had celebrity platforms. As one of our alleged child victims put it to us, they had the status and wealth to speak out. Whereas our alleged victims, these were kids who had nothing, and their lives were ruined. They had fears and anxieties, and there was no fallback for them. There was no support network. Most, if not all, came from broken homes. They had nothing. And so, when we started reaching out to them, they’re like, Hey, hold on here.

SINGER’S BOYS

French: The first person we talked to who was intimately involved with Singer was Bret Skopek. As Bryan put it, Bret was Bryan’s “favorite late-night snack” for a couple years, starting in 2013. He’d met Bryan at a party and they became a late-night hookup thing. I think Bret felt used and abused, and he was willing to talk.

He was 18 or 19 when a lot of this stuff happened. For Max and me, it was the first confirmation that the stuff about twink parties that you hear about, or that you read about being reported, there’s actually something to that. You talk to somebody who’s there, who’s seen it, who’s lived it. It confirmed the validity of the other reporting.

Along the way, I spoke to another journalist who had worked that beat years before, and he said, “There’s another guy that I never wrote about, that you should talk to.” That source ending up leading us to one of the aliases in the story, “Ben.” He’d been homeless for a while. He had some experiences with Singer as a teenager. I began the weeks-long or months-long process of trying to get in touch with him. I’d heard he was living in a car in Arizona. We didn’t know how to track him down.

Then we got in touch with Jeff Herman [the lawyer who had represented a client in a previous suit against Singer]. There were a couple of weeks of negotiations about having a conversation with Jeff. We ended up flying down to Boca. It was March 29, over spring break.

Most of that conversation with Jeff was off the record, but he agreed to connect us with two clients: Cesar Sanchez-Guzman and a guy we’d never heard of named Victor Valdovinos.

I try to say as little as possible during these interviews. On my laptop, covering the little camera hole, I have this little piece of tape that says, “Say less.” You try to be as gentle as you can. You allow the person who’s reliving this thing to fill up the silence and tell their story. In instances where it would get hard for them to talk, in instances where people are making allegations of sexual assault, your job is to investigate the story as thoroughly as you can and make sure that the allegation that they’re making is credible. At the same time, I’m also a human being, you know? So you try to stay as detached and objective as you can, but also reassure them that I’m here. I’m listening.

Potter: Meanwhile, we’re feverishly tracking down ‘Ben’ [a pseudonym].

French: He had been around DEN. He knew all the players, and he provided a pretty clear window into West Hollywood at that time. And he’d had sexual experiences with Singer when he was 17 or 18. ‘Ben’ helped us corroborate other allegations and other details that we were getting from different sources.

Potter: ‘Ben’ had two sexual experiences that he can recall with Bryan, and would tell you, as he told us, he would classify that predatory.

French: Still, even with Ben, Cesar, and Victor in hand, I’m not sure we felt then that we had a story yet. The feeling between the two of us was pretty steadfastly, If there’s three, could there be more?

LATE APRIL

Potter: Around that same time, we each found a cache of new documents that would prove valuable in that they would both lead to another series of sources that would steer us toward, in the sources’ respective opinions, several potential other alleged victims.

That started another wave. This is a lot of names, a lot of potential alleged victims. That led to other potential alleged victims, which lead us to Eric and Andy.

We got an email from Singer’s attorney: I hear you guys are working on a story that may address my client, Bryan Singer. At the time he sent it, we had a reasonable idea that his client was probably going to be a part of the story, but we weren’t entirely sure what it was. We’re still looking at DEN hard, and a lot of alleged unsavory characters are coming on and off of the stage of DEN.

At this point, though, it’s clear we have what we believe to be concrete and substantial alleged victims of Bryan. We more or less write back and say, “Thanks for reaching out. We’re still reporting. We’ll get back to you when we have questions.”

ERIC AND ANDY

Potter: There’s still a shit-ton of interviews and leads being chased out from the caches of documents. Alex gets a response from his outreach to Eric and Andy, so he did phone interviews with them, separately.

French: From the first conversations, I immediately found them credible. They made allegations that were rooted in details.

Potter: They were naturally, organically, in the most uncontrived way, clearly conversant in detail with the entire framework of DEN and what Bryan’s connections were to DEN at that time. They’d say detail X, detail Y, detail Z, and in our respective heads, we’re going, “Ding! Ding! Ding! Ding! Ding!”

French: The Ferrari was another big one. Victor claimed that Bryan said, “I have a Ferrari. I’ll take you for a ride in it.” We ended up confirming with three sources that, yeah, Bryan was driving his Ferrari at the time.

WRITING

French: We start writing in August or September.

Potter: During the reporting and writing, we were very conscious of homosexuality and pedophilia as a topic. Early on, there was a couple of instances where sources we would talk with would say, almost from the jump, that we were on a gay witch hunt. They would be very animated and understandably defensive. This is a constituency of humanity that has been on the wrong end of a lot of shit. To discredit the sensitivity or their initial reaction, I think, it’s just not cool. It denies reality. So I would say, more or less, Talk to me about where you’re coming from on that. And we would talk. It would go away. There’s unsavory humans in the heterosexual community and there are unsavory humans in the homosexual community, and it is what it is.

French: The first draft took three or four weeks. We filed in about September. We were aiming for the December/January issue, which would have been on stands sometime around November.

EDITING

Potter: It was a pretty standard editing process. [Robert Scheffler, Esquire’s research editor, began the fact checking in September.]

On October 10, Alex and I went to New York to close. We spent two days in a room with Michael [Hainey, editorial director] Bruce [Handy, features editor], Bob [Shreffler], and a Hearst lawyer who had read the quote-unquote final draft. Jay [Fielden, Esquire’s editor-in-chief]…would pop in depending on where we were in our discussions.

This lawyer was really good. She was thorough. When you’re doing a piece like this, the attorney is your best friend. There’s no upside to being adversarial. The lawyer started out by saying she’d been around the block. She’s vetted pieces, and said, very politely and assertively, that if she felt like a piece wasn’t ready for publication, she would say so. She asked good questions, challenged us on sourcing. After two days, there was a debrief where Jay was present. The attorney said she didn’t see any reason why this doesn’t run, but she gave us a punch list: Dot an I; cross a T.

French: The detail about Singer grabbing his boyfriend by the hair and pulling him down the hall came in late. That was big—for me, at least. That is an animating detail about who Singer was and how people acted around him.

Potter: An eyewitness said they chalked it up to a “Bryan Singer moment.” Like it’s nothing. I said to this witness, “Dude, I gotta tell you. I got my flaws, but if I grabbed somebody by the hair and dragged him down a hallway, I’d hope someone would not say, “That’s a Max Potter moment!”

Oh, and Bryan put out his own Instagram statement on October 15th, in advance of when he thought the Esquire story was going to publish.

HEARST

French: Then a week went by. We didn’t hear shit. Then we get a call on Wednesday, October 24, around 4:00. My kids had just gotten home, and I’m standing in the garage. On the other line is Jay Fielden, and he sounded so fucking confused. He had just been in a meeting at Hearst, with top executives, including Troy Young, president of Hearst Magazines, and chief content officer Kate Lewis. He did not sound like himself. It sounded like he’d been hit in the head. He didn’t know what was happening.

Potter: He was trying to be as positive and supportive as he could. He says the piece isn’t going to run in the December/January issue, and it’s not going to go online. Then he said, “But the upshot is…” Then he talked for a while. Once he got done, I said, “Jay, a few minutes ago you started to say what the upshot is. What exactly is the upshot?” He said the piece wasn’t dead. And he relayed what he believed the executives had communicated to him, which Alex and I found bizarrely contradictory.

The executives presented, essentially, two options. The first is we make Bryan Singer a blind item. I didn’t say anything. Alex didn’t say anything. The second option is to run a longer version, serialized on the web. It didn’t make any sense. The blind item idea struck me as preposterous on the face of it. I mean, why even bother? With the other idea—of running longer, as a serial on the web—I was like, “So, we identify Bryan? Or not?” It was starting to feel like a slow-walk-into-a-jog-to-a-kill, to me.

French: At one point, Jay asked if we can find more victims. “They’re looking for more presentable victims. The guys you have in your story are all troubled. They’ve had problems with drugs or alcohol. They’ve been arrested.” And we were just like, Wow.

Potter: More presentable? Of course these alleged victims had their lives turned upside down! That’s kind of the point. I told Jay I didn’t even understand what strategy or deliverables Alex and I are supposed to try to get. Because we’ve just gone from a blind item feature on Bryan Singer to a longer, serialized version. What were we supposed to do right now? So we asked for a meeting with the Hearst executives so could get some clarity.

Reporter Alex French. Photo by Larry Fink.

French: Jay comes back to us a couple days later, and says we’ve got a meeting at 3 on Halloween. I go to New York, Max attends by phone. It’s in Kate Lewis’s office, and it’s me, Bruce Handy, Michael Hainey, Helene Rubinstein, who is the managing editor, and Jay. Kate said to us, “It seems to me you’ve got a bunch of guys who had consensual sex with Bryan Singer. And they’re all troubled.” I said, “They’re all minors!”

Potter: Kate said—I’m paraphrasing—“I realize we could have an NBC-Ronan Farrow situation on our hands.” And I was like, Huh, that’s interesting! And then she said, “We could have a Weinstein-Cosby story. Or we could have UVA and Rolling Stone.” I didn’t know what to say. I mean, we had a story with over 50 sources, corroborated as much and you could corroborate it. I didn’t know how to react!

I was on the phone, pacing in my house in Denver, and I was like: I don’t even know how this conversation continues.

French: When the meeting started, I explained to Kate how the story came together. Without getting too in the weeds about identities, I said, These sources didn’t approach us—we had to find them. It was hard and it was time consuming, and we backed up their stories. I explained how all of their stories clipped together and overlapped; it was the muscle tissue that connected all of these guys and their stories. She moved on from that pretty quickly. I don’t know if she believed us.

Potter: She’d say, “Well, did you do this?” And we’d say, Yeah, we did that, and for what it’s worth, we did this, this, and this. And she’d ask, “Well, did you this?” And we’d say, Yeah, we did that and, for what it’s worth, we did this, this, and this. She asked why that wasn’t in the piece. We said we’ve been through several rounds of edits, it’s been through legal, and a myriad decisions have been made and discussed. The piece is the piece.

Kate asked us to write what she called a ‘corroboration memo.’ Bullet-pointed.

ICYMI: Reuters publishes ethically questionable story

French: Give me a short memo about why we should believe these guys you put in the story.

Potter: She wanted a memo that showed our reporting methodology. Alex and I spent the next 24 hours detailing it, without disclosing the identities of our alleged victims. How we got to each one, what we had done for corroboration. We included an excerpt of our interview transcripts with each one to demonstrate that these people were alleged victims, and they were hurting.

Jay, Michael, and Bruce loved it. We got word back that Kate was more or less impressed by the memo, and she was gonna advocate that the story run. I remember that because it was good news. And then a couple days go by.

French: It was agony.

Potter: Because what do we tell our sources, these alleged victims, if it doesn’t run? Generally speaking, every one of them conveyed that they just didn’t think this piece—their truth—was gonna run. Regardless of what the kill reasons were, they believed that—pardon the pun here—Bryan has this Keyser Söze-like power that was gonna prevent the piece from running. They had expressed this over and over. And they’re saying, “Can we trust you? Are you guys for real?” And we’re telling them, “Yeah, we have the full support of Esquire! If we thought this wasn’t gonna run, we wouldn’t be here.”

French: Days go by, and we get this call from Jay.

Potter: I was on a road trip with a buddy who was moving from Denver to San Francisco. A conference call with me, Alex, Jay, Michael, and Bruce. We had just passed Needles, California. You could immediately tell Jay was demoralized. [He] said, “I just got a call from Kate, and I got some bad news.”

He sounded like somebody had scooped the soul out of him and threw it at his feet. “Kate just told me to tell you guys that the piece is killed.”

I asked why. She said, according to one of our editors, “It just seemed like you had a bunch of guys who had consensual sex with Singer.”

French: “Yeah,” I said, “it’s called grooming.” Like, there’s a term for it.

Potter: I said to Alex, “You’re wasting your breath.” Jay said, “Alex, I’m afraid Max is right.” I knew, in my mind, that within 24 hours we were gonna have that piece on another editor in chief’s desk.

THE ATLANTIC

French: One thing I have learned with Max throughout this process is he has a really profound professional patience. We’ll get there. We’ll figure it out. But let’s pause and count to a million, and think it through. Max is better at that than anybody I’ve ever met.

The next morning, we reconvened. We talked about where the story fit. Max had this idea of The Atlantic.

Potter: I sent an email to [Atlantic editor in chief] Jeff Goldberg. It was two paragraphs, something like that; a quick thumbnail. I said, “If you want to read the piece, give me a shout. We want to move quickly.” Tuesday we’d had the call with Jay, Wednesday I had sent it to Jeff, and by Friday we’re on the phone having the conversation.

MORE EDITING, MORE LAWYERS

Potter: Denise Wills. She’s an amazing editor.

French: Total ninja.

Potter: I feel like, in pretty shitty circumstances, God did us a solid by putting us where we ended up. The other thing is, as she herself put it, Denise had the benefit of getting a piece that had already been through a couple drafts, and edited by some really smart minds at Esquire, and already through a fact check and legal vetting at Hearst. I don’t mean to diminish the work that we all put into it at that point, but it was kind of like moving seashells around on the sandcastle. The sandcastle was built.

In terms of the legal vetting, The Atlantic was even more rigorous and robust. Imagine you’re The Atlantic, and this piece comes your way and it’s been killed by Hearst executives. The Atlantic wants to be all the more prudent and thorough and rigorous, both in their fact check and in their legal vetting process. We got it, and how. It was a longer, more intense colonoscopy than at Hearst. But that’s understandable, under the circumstances.

French: They did want to know the story of why it had been killed. And we told them. Jeff Goldberg was just as incredulous as we were at what unfolded.

AFTER PUBLICATION

Potter: I gave a draft of the piece to my teenage sons to read, to get their feedback. Suffice to say, it was a moment for me.

This piece took us away from our families. We just weren’t present. If you want to talk to somebody that is understandably been pissed off and frustrated, you should interview Alex’s wife and my two sons. I don’t know how many trips we took. There were a lot. And when we were here, we weren’t here. We were present, but we weren’t present.

French: I’m a pretty reserved guy, and I have lately been prone to these bouts or spells of very intense emotion. The guys who’ve survived the abuse and some of the stuff that didn’t make it into the story really rattled me. And then, also, just sort of the emotions I had over of dealing with the situation with Hearst. It’s been a process. You’re talking to us now, three weeks out of publication to the web, and I just feel like I have an adrenaline hangover.

French: Max, if you knew then what you know now about what we’ve been through with this, and the toll that it’s taken, would you do it again?

Potter: Yes.

French: I would, too.

ICYMI: An early, unsuccessful, attempt at #MeToo in Hollywood

Correction: An earlier version of this story mischaracterized the date on which The Atlantic ran its Bryan Singer story, and misspelled Robert Scheffler’s name.

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.