Sign up for The Media Today, CJR’s daily newsletter.

In late July 2013, three journalists at The Guardian, under orders from British authorities, bore down with grinders and drills on computer hard drives containing documents stolen by US intelligence contractor Edward Snowden. The government agents stood by as metal dust spewed and newsroom cameras recorded the historic scene.

The files contained information on massive US and British electronic surveillance programs designed to spy on terrorists and ordinary citizens by collecting their personal data. The paper had been publishing the information for a month, refusing government demands to stop, when the authorities showed up.

They had prepared for the state’s strong-armed tactics by giving copies of some files to their would-be collaborators in the United States, The New York Times, where the government doesn’t practice prior censorship. But as the Times prepared to publish, former executive editor Jill Abramson told me recently, she sought answers to a critical question: Is the Pentagon Papers’ Supreme Court decision against prior censorship iron-clad?

Her friend and First Amendment expert Bruce Birenboim felt the law was on Abramson’s side. “There is a very heavy presumption against prior restraint under the First Amendment,” Birenboim and an associate wrote in a 30-page memo. Legal action after publication couldn’t be ruled out, but unless the information truly exposed the United States to immediate and irreparable harm, it was unlikely.

That chain of events in 2013—Abramson’s question, the lawyers’ answer, and the Times’ decision to publish—symbolizes the profound and lasting impact of a body of work that won The New York Times the Pulitzer for Public Service in 1972.

This heroic act of journalism, and the legal ruling it forced the US Supreme Court to make, still stand today as the most powerful legal and moral weapon in the American media’s battle against government secrecy. Whereas Britain and most other countries reserve the right to censor the news, American courts took that option off the table almost 45 years ago, after weighing the role of the media in American life versus the government’s desire to keep national security programs secret.

Over the past year, in The Washington Post alone, the words “covert” and “clandestine” were used approximately 450 times.

“The guarding of military and diplomatic secrets at the expense of informed representative government provides no real security for our Republic,” Justice Hugo Black wrote in his opinion. “The Framers of the First Amendment, fully aware of both the need to defend a new nation and the abuses of the English and Colonial governments, sought to give this new society strength and security by providing that freedom of speech, press, religion, and assembly should not be abridged.”

To ordinary journalists, the value of secret war documents leaked by Daniel Ellsberg in the fury over the Vietnam War is more basic. “They established the understanding you could publish anything you could lay your hands on and no one could stop you,” says Marcus Brauchli, former executive editor of The Washington Post and managing editor of The Wall Street Journal.

That is one effect of the Pentagon Papers. In legal spheres, there is no doubting the impact this fearless journalism had on a covert plan to fight a controversial war. As a reporter for the Post, I have benefited from its protections many times.

But did the Pentagon Papers actually help curtail government secrecy? There, the news is not so good.

President George W. Bush, for example, chose to deploy classified units from the CIA, NSA, and the military to go after those responsible for the September 11 attacks, thus ensuring that the public would know very little about how this global war was fought. President Barack Obama expanded these covert units and increased both the pace of operations and the secret universe in which they are conceived, planned, executed, and evaluated.

This penchant for operating on “the dark side,” as then Vice President Dick Cheney so famously announced on television five days after the attacks, led to the creation of an alternative, secret geography within the United States. It is now inhabited by more than three million federal employees and one million private contractors, all with security clearances.

Meanwhile, the government is applying ever more strident measures to stop national security reporters from doing our jobs. Individuals are shamed as traitors. Lives are crushed so the government can send a message. Thomas Drake, who shared unclassified facts about NSA waste with a Wall Street Journal reporter, had his life upended after he was indicted on espionage and other charges, only to see the Justice Department drop the case on the eve of trial four years later.

New York Times reporter James Risen famously spent seven years resisting court efforts to force him to identify confidential sources, only not for the many front-page exposés he wrote about current CIA and NSA programs. They went after him for a chapter in his book about a 10-year-old CIA effort against Iran. Abramson believes the intelligence community was out to avenge Risen’s newspaper work.

“I think they were trying to avoid a Pentagon Papers situation” by not prosecuting the Times, Risen says. The case against him was dropped last year on the eve of trial against the alleged leaker. “They decided it was easier to come after me alone, for the book.”

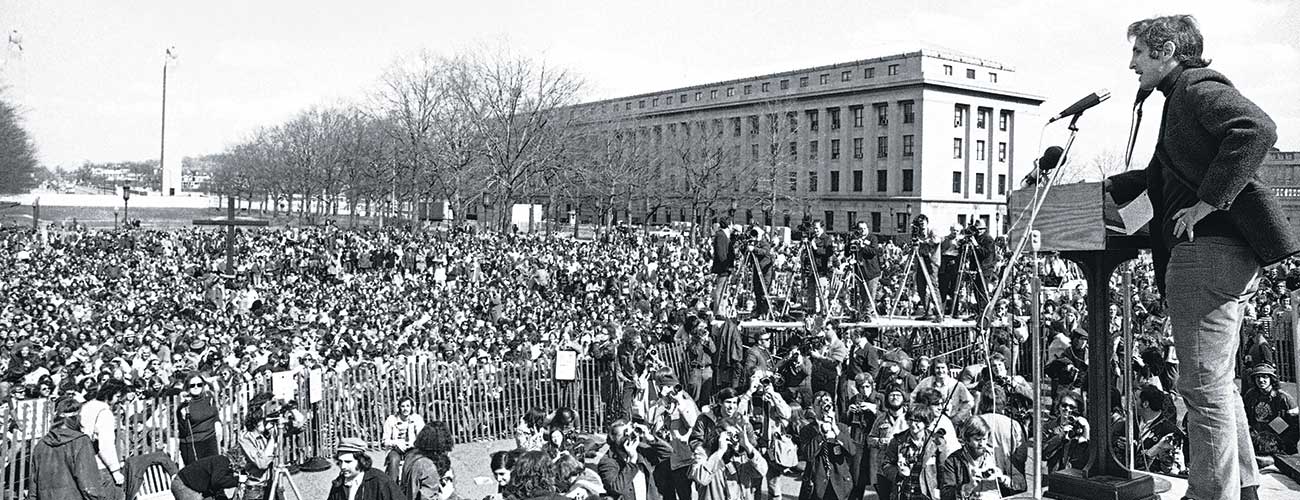

Daniel Ellsberg speaks at a press conference following publication of “The Pentagon Papers.” (Hulton Archive / Getty Images)

The Justice Department has launched dozens of leak investigations, seized reporters’ phone records, and threatened prosecutions. The department, too, has weakened some whistle-blower protections to stop employees from leaking information about government programs whose legality they question.

And yet classified programs continue to pop up in the news. Over the past year, in The Washington Post alone, the words “covert” and “clandestine” were used approximately 450 times. Most of these stories did not prompt a leak investigation because most involved some senior White House, intelligence, or defense official letting the story out. The Obama administration has continued the tradition of selective leaks, following every prior White House, including Richard Nixon’s, both before and after the top-secret Pentagon Papers made news.

Indeed, the path from Daniel Ellsberg to Edward Snowden is a twisted one, seeming to take us a long way, and yet nowhere at all.

The mildly titled “History of US Decision-Making Process on Vietnam Policy” was commissioned in June 1967 by a distressed Defense Secretary Robert McNamara. Three dozen government and contract researchers were given anonymity to work on the secret report without fear that their names would ever become public. By the end, they had produced a 3,000-page narrative of the history of US involvement in Indochina from World War II through the May 1968 Paris Peace Talks. They appended 4,000 pages of documents. They interviewed no one.

Today, reading the Pentagon Papers, as their work was short-handed, feels like reading an analysis in Foreign Policy magazine of the sprawling current wars in the Middle East and Asia. Committed then to saving South Vietnam from takeover by the Communist north, successive administrations stuck to that original goal and refused to re-evaluate it or adjust policy as events unfolded. To that end, the White House undercut emerging political solutions, intensified covert wars despite intelligence assessments they would not succeed, and backed corrupt leaders who had little popular support.

Some 37,000 US troops, 95,000 from the French colonial army, and upwards of two million Vietnamese had been killed by the time the study began. At home, the nation was engulfed in a culture war at whose core lay deep distrust of government and establishment powers writ large.

Into this fracas stepped Daniel Ellsberg, a RAND Corporation researcher and former defense official with a decade of experience evaluating US policy and the Vietnam War.

Ellsberg had met a determined Times reporter named Neil Sheehan back when Sheehan, then in his 20s, was UPI’s correspondent in Vietnam. After trying in vain to get several senators and National Security Adviser Henry A. Kissinger to pay attention to the report, Ellsberg gave it to Sheehan.

The Times spent four months digesting and summarizing the 7,000-page study. Forty-four writers, editors, and researchers analyzed the information, comparing it to public government statements and actual decisions, and then cross-referencing it with 40 books, as the Times’ Pulitzer submission described.

On June 13, 1971, without consulting or alerting the government, the paper began its series with such understatement that some involved believed readers would miss the story altogether: “Vietnam Archive: Pentagon Study Traces 3 Decades of Growing U.S. Involvement.”

The lede was equally muted:

A massive study of how the United States went to war in Indochina, conducted by the Pentagon three years ago, demonstrates that four Administrations progressively developed a sense of commitment to a non-Communist Vietnam, a readiness to fight the North to protect the South, and an ultimate frustration with this effort—to a much greater extent than their public statements acknowledged at the time.

Nixon was slow to react to the stories until he had a conversation with Secretary of State Henry Kissinger, who told him, “I’m absolutely certain that this violates all sorts of security laws.”

“People have gotta be put to the torch for this sort of thing . . . this is terrible,” Nixon fumed over the leak and the Times’ decision to publish, according to White House transcripts.

After a second day of stories, Attorney General John Mitchell sent a telegram to the Times publisher asserting that publication of the material violated the Espionage Act. He requested that the Times stop publishing any further information and return the documents to the Pentagon. The Times declined both requests.

Ellsberg had become a human thumb drive, passing out copies of the original document to still more publications with the same strategic sensibility as Snowden would display four decades later.

The complaint for a court injunction followed the next day, citing “irreparable injury to the defense interests of United States,” but with no specifics. Meanwhile, The Washington Post, smarting over the Times’ exclusive, tracked down Ellsberg as the leaker and got a copy for itself.

As Post editors and reporters scurried to prepare their own story, a fierce battle erupted between the newsroom and the paper’s reluctant attorneys. Reporters were threatening to resign. Publisher Katharine Graham sided with the newsroom, and the Post took its place beside the Times on the frontline against censorship.

Ellsberg, meanwhile, had become a human thumb drive, passing out copies of the original document to still more publications with the same strategic sensibility Snowden would display four decades later. In all, 20 newspapers published articles based on the documents. After a 15-day legal struggle that ended at the Supreme Court, the matter was settled with a 6-to-3 decision against the government.

“The dominant purpose of the First Amendment was to prohibit the widespread practice of governmental suppression of embarrassing information,” wrote Justice William O. Douglas. “A debate of large proportions goes on in the Nation over our posture in Vietnam. Open debate and discussion of public issues are vital to our National Health.”

Ellsberg was still on the hook. He turned himself in once the court lifted the injunction. He and Anthony J. Russo, a colleague who helped him copy the documents in a Hollywood ad agency office owned by his girlfriend, were charged with violating conspiracy, theft, and espionage laws.

When I read the opinion again recently, I was most struck by the court’s nod to the informal way responsible journalists and government officials had learned to deal with each other on national security matters. It was true then and still is today. Max Frankel, chief of the Times’ Washington bureau, described it best in an affidavit:

Without the use of ‘secrets’ . . . there could be no adequate diplomatic, military and political reporting of the kind our people take for granted, either abroad or in Washington. . . .

Practically everything that our Government does, plans, thinks, hears and contemplates in the realms of foreign policy is stamped and treated as secret—and then unraveled by that same Government, by the Congress and by the press in one continuing round of professional and social contacts and cooperative and competitive exchanges of information. . . .”

He went on to describe what he called a simple rule of thumb that had developed between the press, Congress, and the administration:

The Government hides what it can, pleading necessity as long as it can, and the press pries out what it can, pleading a need and right to know. Each side in this ‘game’ regularly ‘wins’ and ‘loses’ a round or two. Each fights with the weapons at its command.

When the Government loses a secret or two, it simply adjusts to a new reality. When the press loses a quest or two, it simply reports (or misreports) as best it can. Or so it has been, until this moment.

He was right. The Pentagon Papers decision tilted the power balance between the government and the media to the media’s side. The decision to publish rests with the owners and editors of US media outlets. Period.

This fact infuriates the US national security establishment to this day. How many times has a mid-level intelligence or Pentagon officer, seething over an unauthorized leak of classified information, sneered the words: “Who elected you?” in the face of a reporter seeking comment or context for a story about a secret operation or a classified policy?

More than once I’ve shot back, “The US Constitution.”

At the same time, I can’t help but imagine how the other side must feel when they compare the ad hoc backgrounds of reporters with the structured career paths, training, oaths, pledges, polygraphs, and background checks of the government’s secret keepers. Through their eyes, it must seem like a wacky system. Why should reporters have the right to publish any secrets they find when the gatekeepers of that classified information have to endure a labyrinth of security screenings?

There’s a good reason why. All governments lie and all use secrecy to cloak their wrongdoing and their poor judgments. Our protection exists to uncover this. White House aide H.R. Haldeman made the same point to President Nixon in the Oval Office the day after the Times series began.

Edward Snowden, broadcasting from Russia, appears at a teleconference on human rights in Paris, 2014. (Antoine Gyori / Corbis)

“Out of the gobbledygook, comes a very clear thing,” he told Nixon, according to tapes of the conversation. “ . . . You can’t trust the government; you can’t believe what they say; and you can’t rely on their judgment; and the—the implicit infallibility of presidents, which has been an accepted thing in America, is badly hurt by this, because it shows that people do things the President wants to do even though it’s wrong, and the President can be wrong.”

(In the same conversation, Haldeman surfaces the idea of a clandestine team to steal copies of the documents held by the Brookings Institution. The black-bag team became known as the Plumbers, the ones who gave us the Watergate break-in, which cemented the role of investigative journalism in civic life. The Plumbers also inadvertently helped Ellsberg and Russo. The judge dropped charges against the men in 1973 after learning Ellsberg’s psychiatrist’s office had been burglarized. The Plumbers, it was later discovered, were behind the late-night antics.)

With immunity from censorship enshrined in the Pentagon Papers decision, however, the media has a greater responsibility to be thoughtful about what it publishes and to give government the chance to make its case, argues Brauchli, who has confronted numerous government demands to not publish secret programs. “The scales always tip a little in the government’s favor because of its inherent information advantage, but the journalists make the call, more confident in knowing that they have given the government the opportunity to critique, analyze, refute, object to, disagree with, and explain the relevant subjects.”

But it is not as easy as you might think to act responsibly.

On at least three occasions, I’ve presented elaborate details contained in an upcoming story to intelligence officials. One time the Post hosted meetings for eight distinct intelligence and military agencies to explain our findings—only it led not to any reasonable response, but to a simple request not to publish any of it after an hour-long presentation. In these instances, I sought out confidants from the diplomatic, military, and intelligence world to help my editors and me make decisions on what would be truly damaging to publish.

While reporting for a 2005 story about the CIA’s secret prisons abroad, I received a phone call in my hotel room in Warsaw one morning from an official at the CIA. How she knew I was in Poland, I don’t know. The voice on the other end of the line told me my questions were upsetting senior intelligence and military officials in the Polish government. Please stop your reporting and come into CIA headquarters, she said. I told her I would come in when I was finished. (I have to admit, the large-jawed hulk driving me around became much creepier-looking after that call.)

Whereas Britain and most other countries reserve the right to censor the news, American courts took that option off the table almost 45 years ago.

When I returned, my editors and I were invited to a series of meetings that included the CIA director and the director of national intelligence. They knew by then that I had discovered a highly sensitive operation—CIA prisons around the world where alleged terrorists could be freely interrogated and even tortured without the public’s knowledge and without giving prisoners conventional legal protections. The White House tried to dissuade us from publishing anything. As in the case of the Pentagon Papers, these officials offered only the most generic reasons, without specifics: Allies won’t work with the US anymore; terrorists might retaliate and endanger US forces.

The final meeting was held in the White House between President Bush, his national security team, and the editor and publisher of the Post. They only repeated the previous requests and reasons for killing the story altogether. Executive Editor Leonard Downie pressed for specifics. He got nothing, only a hint on his way out the door.

As they were leaving, Director of National Intelligence John Negroponte, the only career diplomat in the room, put his arm around Downie: “You’re not really going to name the countries, are you?” he said, according to Downie’s recollection of events.

“Is that what you’re most concerned about?” asked Downie. Negroponte repeated the same statement.

After another day of debate, Downie had us remove the country names, but he agreed to my counter-proposal that we include “Eastern Europe” as a description. Those two words were enough to set off a series of governmental and journalistic investigations in Europe that ended several years later with the truth: Poland, Lithuania, and Romania had set up CIA secret prisons.

None were attacked by terrorists. All maintain fine relations with the United States, with some strains for reasons unrelated to my story.

James Risen and his editors at the Times held many talks with the White House before his and Eric Lichtblau’s initial warrantless wiretapping story ran in December 2005. They sought guidance on which details officials believed would truly damage national security.

Most of what they received back was hyperbole: “You’ll have blood on your hands,” the White House told them. The scare tactic worked. Times senior editors killed the story, twice, in 2004.

Risen’s sources were frustrated. They believed the program was unconstitutional and that the public deserved to know about it. After the story ran, “our sources all approved of what we did,” he said when we spoke recently. “None turned against us.”

Sometimes, reporters engage in the same types of stealthy methods as the people they cover. Barton Gellman, working for The Washington Post on the Snowden stories, had a coterie of paid and pro-bono security experts help him set up a security system to keep the NSA files secure.

He assumed that “high-end adversaries,” among them state-sponsored hackers, would attempt to steal copies. So he requested editors learn the arduous PGP key encryption system, and he used an encryption app to talk by phone. He insisted that supervisors parse out passphrases, security credentials, locks, keys, and a safe combo so no one person but him could gain access alone.

The government is applying ever more strident measures to stop national security reporters from doing our jobs. Individuals are shamed as traitors. Lives are crushed so the government can send a message.

A heavy safe sat on the first floor, behind a reinforced door with a non-standard lock and electronic access control. A video camera monitored the door.

On the seventh floor of the Post building, a safe room was set up so that a small number of reporters could view material on computers that had been freshly wiped and encrypted. Computers that could open the full archive had ports sealed with physical locks and tamper-evident covers on the screws that opened the case. When a hard drive failed, “I physically, thoroughly destroyed it,” Gellman wrote via email.

Before each story was published, he spent hours on the phone with the government, sometimes with up to a half dozen subject matter experts.

Despite his scrupulous precautions, US intelligence officials refused to set up a secure way to communicate with him about the documents. Instead, to thwart possible adversaries that might be eavesdropping, they would play a serious game of 20 Questions, with officials using copies of documents in front of them to converse.

Gellman would identify a document by title, date, and author, and particulars like “page 7, paragraph 3,” and then verbally guide intelligence officials on the other end of the line to particular passages, he says. “No, not that one, the one with the two rhyming words . . .”

“They got tied up in their own regulations,” says Gellman, whose book, Dark Mirror: Edward Snowden and the American Surveillance State, will be out in September. “They can’t have classified information on an unclassified network or machine; I have no clearance (obviously), so I can’t use a classified network or machine; and they wouldn’t connect with my unclassified machine remotely (or even to the public internet) from a classified machine. Checkmate. A creative side channel was called for, but it wasn’t in their toolbox.”

It was arduous and time consuming with the competitive Guardian also on the chase. “We consulted with the government on every story, and on every fact in every story,” Gellman told a panel audience after the series ended.

And still, he confessed, “I worried all the time about where to draw the line.”

As the Snowden disclosures drew public fire, Obama appointed a commission to examine the programs he disclosed. It found that the bulk data-collecting operation “was not essential to preventing attacks” as the intelligence community had insisted. It said the NSA “should not be permitted to collect and store massive, undigested, non-public personal information about US persons for the purposes of enabling future queries and data mining for foreign intelligence purposes.”

Many factors have rattled American stability and security in recent years, but press leaks aren’t one of them. On the contrary, in the wake of Snowden’s disclosures, the government has been declassifying programs he revealed once stamped secret or top-secret. The Office of the Director of National Intelligence and NSA have published hundreds of pages of legal opinions and compliance reports on NSA programs and the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act court. The CIA declassified 499 pages of the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence’s report on CIA detentions and interrogations.

But the government has not given up its addiction to secrecy. Its latest weapon against journalists is what’s called the “insider threat” program, sold as a way to stop another Snowden but also no doubt aimed at stopping well-sourced journalists, too. Military and intelligence employees are no longer permitted to speak with reporters without prior approval, even on unclassified subjects.

All contacts with the media, even social ones, must be reported. A question on unauthorized media contact has been added to routine polygraphs, which means the only people left to carry on Max Frankel’s grand tradition are the good liars.

I’ve encountered the insider threat program twice that I know of. Two years ago, I served on the board of my daughter’s high school crew team alongside a military officer. After one meeting he pulled me aside to say he had to file a report stating that we served together and saw each other at practices and meets. He rolled his eyes.

The next encounter happened after I started teaching journalism at the University of Maryland. I was invited by the director of the honors program to speak to an undergraduate class studying national security. Days later, the director told me we might have to postpone the class until the two visiting government lecturers who led it got approval to be in the same classroom with me.

They were not covert agents, as I had hoped, just State Department lawyers.

I laughed it off, but I was disheartened. What an enormous waste of the government’s time.

Fortunately, most reporters I know continue to press on. As Adam Goldman, the intrepid Washington Post reporter and Pulitzer Prize winner, told me recently: “I’m constantly amazed by how little we know.”

In honor of the Pentagon Papers, perhaps the first item on that long list of things we still don’t know should be finding the truthful analysis of America’s war on terrorism 15 years later, with no end in sight. One hopes it sits on a secure government hard drive somewhere.

In the many years Dana Priest has been covering the intelligence world, there is one area she has mastered that never makes it into her stories: She knows practically every good garage and dark corner in Washington where one can hold a private conversation. No surveillance cameras. No likelihood of onlookers. No eavesdroppers.

With sources in the CIA, the NSA, and most other intelligence agencies, Priest is meticulous about antiseptic communication. She never puts important information in email. If she calls, it’s rarely to anyone’s office. She’s even sent handwritten letters to sources’ homes proposing a meeting.

She’s not a fan of encryption—she finds her methods more practical and better at protecting sources.

“If someone working at an intelligence agency is discovered to have encrypted email on their computer, it’s a red flag to someone in the government. They immediately become a target of suspicion,” she says.

Once a CIA source proposed to Priest that they meet at a certain suburban restaurant. But she demurred and offered the source a lesson in attentive reporting. The restaurant was an FBI watering hole and they would surely both be recognized.

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.