Sign up for The Media Today, CJR’s daily newsletter.

Videos and photos are ubiquitous, but there’s one place in America where cameras are rarely seen: courtrooms. Federal courts are mostly off limits, and state and local court policies vary, so media outlets historically have hired artists to illustrate major trials. But news budget cuts and increasing courtroom camera access are making these artists a vanishing breed of journalist.

A recent donation of 95 courtroom drawings to the Library of Congress has made the library the nation’s largest repository of such art. The donation is marked by an exhibit through late October. The gift comes from Los Angeles attorney Thomas Girardi, whose most famous case is probably the contaminated-water suit that inspired the movie Erin Brockovich. Three courtroom artists—Aggie Kenny, Bill Robles, and Elizabeth Williams—approached the library in 2015 about acquiring images of major trials the three of them had covered. Girardi agreed to fund (for an undisclosed amount) the purchase of the new illustrations.

TRENDING: Graphic reveals how much local news is suffering

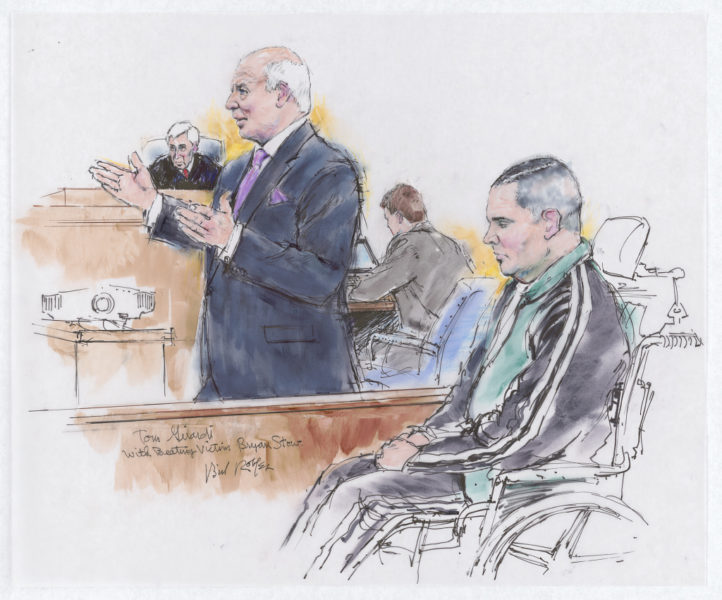

Many of them appeared in the 2014 book The Illustrated Courtroom: 50 Years of Court Art by Williams and Sue Russell. Girardi appears in one of the courtroom drawings in the show.

Tom Girardi with beating victim Bryan Stow, by Bill Robles.

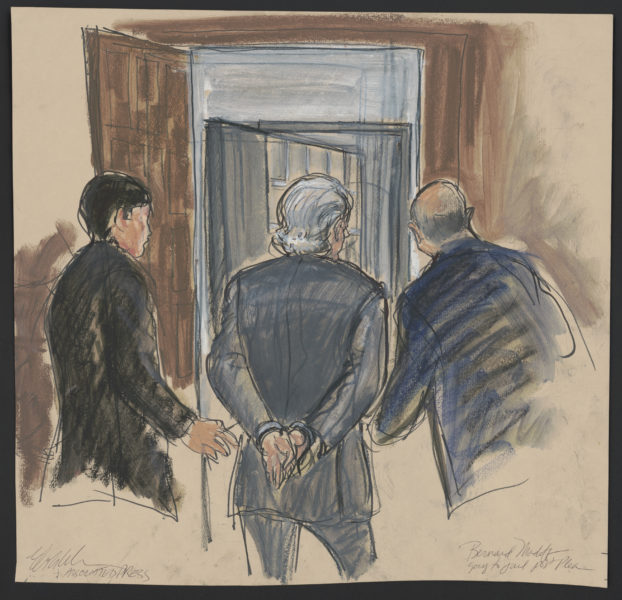

The 98 works in the exhibit, Drawing Justice: The Art of Courtroom Illustration, cover trials from 1964 to the present, including high-profile cases such as Charles Manson, Bernie Madoff, and John Gotti. An interactive video station lets visitors see the drawings as they were used in news broadcasts.

Bernie Madoff, by Elizabeth Williams.

This is the first major show on courtroom drawings in North America, says Sara Duke, curator of applied and graphic art in the library’s prints and photographs division. She tells CJR she views courtroom illustrators as “visual journalists.”

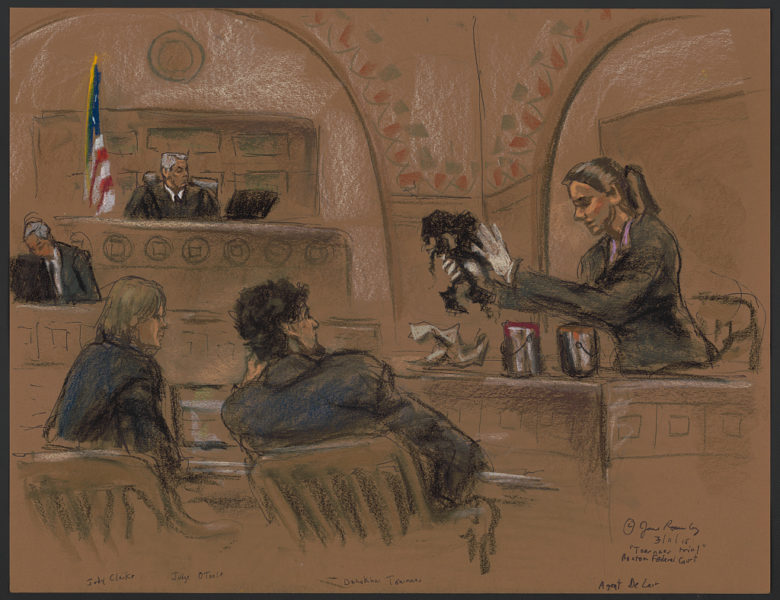

“There are definitely fewer courtroom artists working today than there once were,” artist Gary Myrick tells CJR. Almost all state courts now allow cameras, and news budget cuts have also played a role, leading to use of pooled artists or no artists. New York-based artist Jane Rosenberg, who has covered high-profile trials such as the 1993 World Trade Center bombing case, the John Gotti trial, and Martha Stewart’s securities fraud trial for clients such as NBC, CBS, Fox News, ABC, and CNN, told CJR there were probably 17 artists working in New York in the 1980s, working for TV stations, networks, magazines, and papers. Now there might be five, she says.

Tsaernaev Trial, by Jane Rosenberg.

In Los Angeles, there were seven courtroom artists when Bill Robles started out in 1970, he told KNBC in a 2015 interview. Now two or three artists routinely work trials there, according to the KNBC story.

Most courtroom artists have always been freelancers. There is no central agency or association for news organizations to find artists. The artists have taken different paths to their work. Duke concluded that “a lot of them fell into it.”

TRENDING: A new Meryl Streep, Tom Hanks movie has former New York Times journalists pretty ticked off

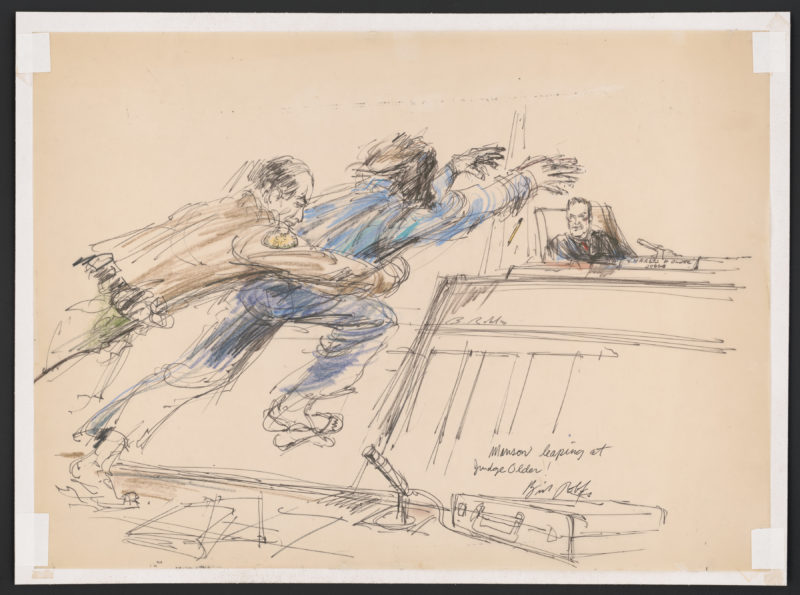

Robles was an ad illustrator, but he was always interested in news, he said at a panel discussion at the exhibit’s opening. He contacted CBS News and convinced them to let him cover the Charles Manson trial in 1970. “I had never set foot in a courtroom before in my life,” he added. On October 5, Manson tried to stab the judge with a pencil. Robles’ image of that incident was the lead story on Walter Cronkite’s broadcast that night. It freezes the action, with a bailiff tackling Manson and the pencil flying in the air.

Charles Manson, by Bill Robles.

Marilyn Church and Elizabeth Williams began as fashion illustrators, drawing clothing on models for fashion designers, ads, and publications. The speed needed for fashion illustration came in handy when covering trials, Church said at the panel discussion. A friend suggested she try courtroom illustration and she attended a trial in Queens, New York, for a week. She took the resulting drawings to TV stations and papers in New York. WABC hired her, and she later worked for ABC, CNN, and The New York Times.

Williams was trying to make ends meet as an artist in Los Angeles and a professor suggested she try courtroom sketches. She developed an ongoing relationship with CNBC and the Associated Press.

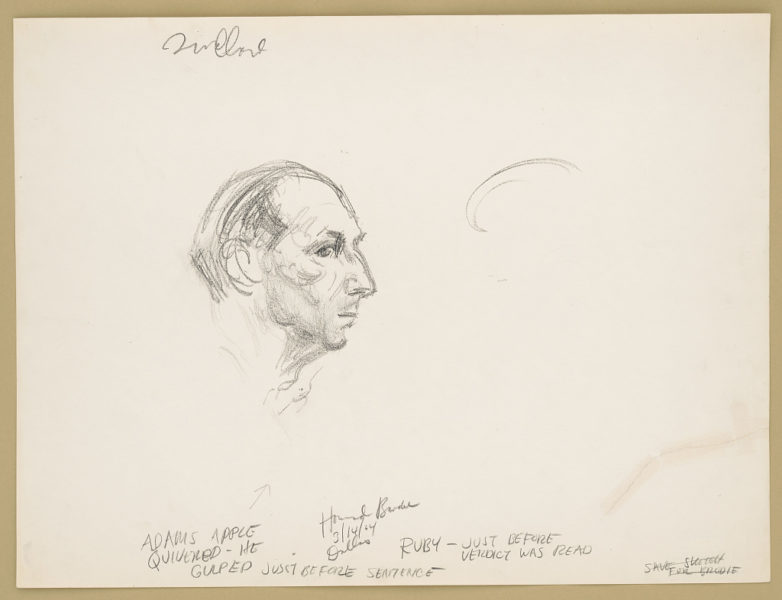

Howard Brodie, one of the first artists to work for TV, was a newspaper illustrator who called an Army buddy who was a CBS executive, the exhibit says. Cameras were not allowed at Jack Ruby’s 1964 trial for killing Lee Harvey Oswald, so Brodie was assigned to cover it.

Jack Ruby before verdict, by Howard Brodie.

Most courtroom artists are reluctant to discuss pay. Church said New York media often pay $350 to $500 per assignment. A Midwestern-based artist cited a figure at the low end of that range for his work, whether for local or national clients. Artists usually retain copyright to their work.

While courtroom sketch artists must work quickly, they use different media (pencil, pen, watercolor, markers, and more) and have different styles. Robles provides detailed drawings of people, with almost no background, which he calls a “vignette style.”

O.J. Simpson during 1996 civil trial, by Bill Robles.

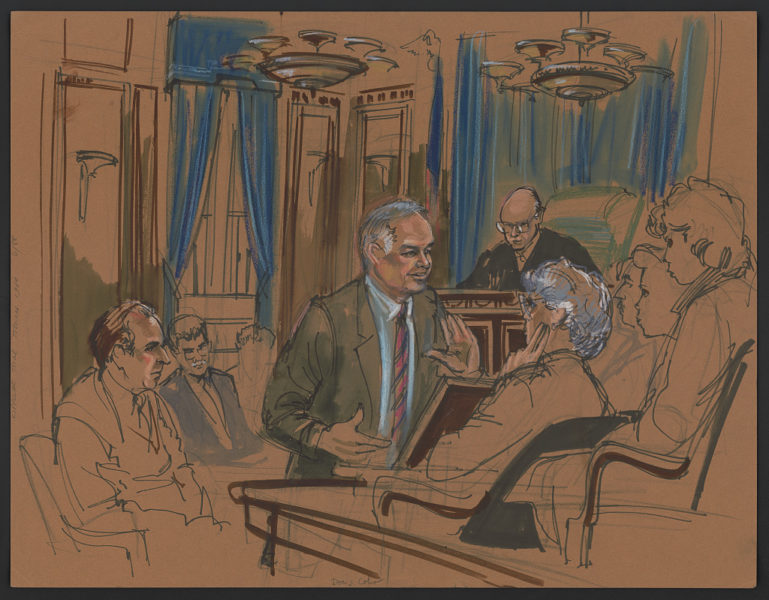

A 1988 Church image of a lawyer talking to a jury focuses on the lawyer. His clothes and face are in color. Everyone else is just a sketch.

Cippolone Tobacco trial, by Marilyn Church.

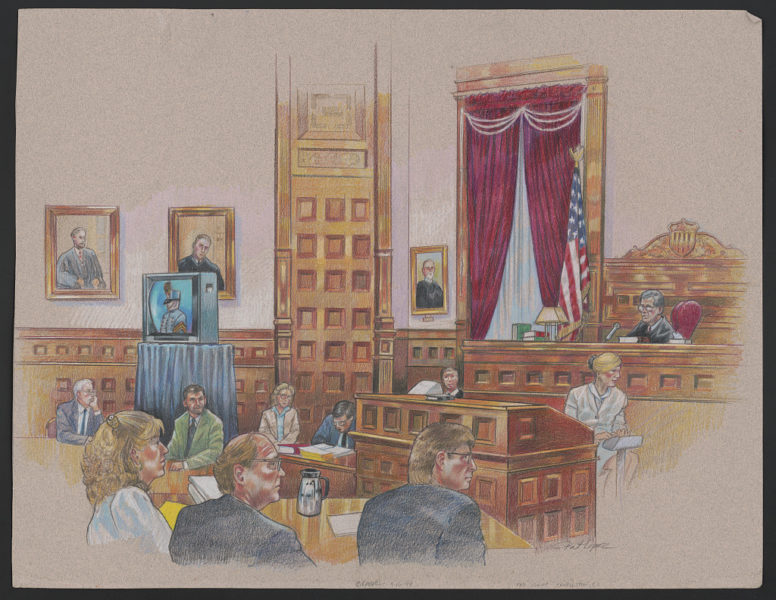

In Pat Lopez’s representational style, she often renders details of the courtroom down to the doorways and the portraits on the wall.

Citadel Federal Court in Charleston, by Pat Lopez.

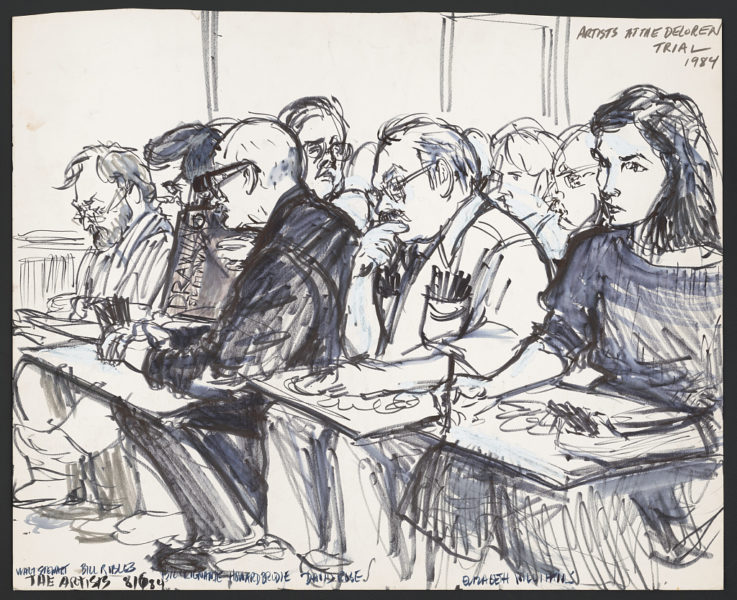

At the panel discussion, Robles said “seating is everything.” All three artists on the panel, Robles, Church, and Lopez, talked about struggling to get a good seat for a good viewpoint. An Elizabeth Williams image of six artists at the 1984 John DeLorean trial shows Howard Brodie with opera glasses attached to his glasses, so he could see better.

Artists at DeLorean trial, by Elizabeth Williams.

Drawing Justice: The Art of Courtroom Illustrations, funded by Thomas Girardi and the Swann Foundation for Caricature and Cartoon, is open until October 28. It is in the Library of Congress Thomas Jefferson Building, 10 First St., Southeast, Washington, DC. It is free and open from 8:30 am to 4:30 pm Monday through Saturday. Tickets aren’t needed. An online version of the exhibit is available here.

TRENDING: 11 images that show how the Trump administration is failing at photography

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.