After scoping the vast terrain of new media ventures, our class of 14 students focused in on 11 experiments we believe represent journalism’s most noteworthy steps forward. None are guaranteed to succeed, but after research, debate, and a final vote of the class, we chose these as the ones most worth watching.

Quartz’s code for confirmation

Perhaps one of the simplest but most effective experiments around today is Quartz’s coded confirmation system.

The online-only publication tested the idea in March on a story about HBO’s standalone streaming service, HBO Now. Misinformation spread on social media as the mainstream media speculated on the details. So Quartz implemented a system that separated confirmed facts from likely truths and what the team didn’t know. A brief, hard-to-miss key taught readers how to decipher the code.

The result? A lively, up-to-date report where visitors avoided journalistic jargon like “reportedly” and “said to be,” for a clean read on something that stood to cause big waves in the TV industry and their own consumption habits. As of mid-April, Quartz hasn’t applied the system, but Zach Seward, vice president and executive editor, says he hopes to use the model in the future.

It is, after all, just an experiment—Quartz’s team says it won’t become a newsroom standard. Coverage of minute-to-minute breaking news, for example, might fail practicality and ethics tests on this model. Those stories are best compiled through live blogs or stories in which new details claim space at the top of an article, says Seward. In its hbo coverage, Quartz erased previously published facts from the webpage—a move that has irked some media watchdogs when done elsewhere.

Some readers criticized the website’s willingness to mix confirmed facts with likely truths. That has increasingly been a characteristic of digital-speed journalism, though; this method merely acknowledged—and streamlined—the practice.

Ultimately, the experiment’s greatest success might be the transparency that it brought to the editorial process. “I think generally readers don’t react well to a tone that pretends to know everything when that is obviously not the case,” says Seward.

What it needs to succeed: A redesign of the coding key.

What might make it fail: Sing it on the wrong stories; reader confusion.

—Jack Murtha

Vox’s card stacks

Even in this digital era, it’s hard to beat flashcards as a way to learn new material. That idea still holds true at Vox.com.

Called Vox Cards, these interlinked pages are the building blocks of the site. The cards describe complex topics, as a way for busy people to stay on top of various ongoing news stories.

Want to know more about Passover? There’s a stack for that. The same goes for domestic stories, like insider Washington policies, and international issues, such as the Eurozone crisis.

The stacks cater to Vox’s general-interest audience. While the whole site explains the news, the cards bring in a format that’s different from other listicles—they’re like miniature current events lessons. And design-wise, the layout is simple and uncluttered.

The stacks are indeed reminiscent of physical index cards. But if it’s educational, it’s mostly for a grown-up audience. When the site launched in 2014, it included stacks explaining federal taxes, immigration, board games—and Game of Thrones. A lot of handy visuals are scattered throughout the different stacks. That includes charts illustrating the Ebola epidemic, maps depicting Israeli and the Palestinian territories, and stock photos to illustrate a stack on Mars exploration.

What it needs to succeed: Stories continue to develop, so there’s a need to stay on top of the content. Otherwise, the repository of information won’t be very useful.

What might make it fail: There’s a need to balance profitability, but the wrong type of advertising might take this product off-course.

—Kay Nguyen

Snapchat’s Discover feature

In January, Snapchat unveiled a new feature called Discover, a huge step for the still-young company—and possibly for the publishing industry. Snapchat’s estimated base of more than 100 million active monthly users lured major news outlets into partnerships with the chance to build a young following where millennials already spend much of their time.

Users access Discover through a small purple button in the top right corner of the app. From there, they can choose between 12 branded channels that display content from legacy media organizations like cnn and National Geographic, or digital heavyweights like Vice and Yahoo News. It’s all there—photos, videos, text, news quizzes—and a lot of it is solid content.

“It really reflects the importance of trying to reach new audiences and being open to new ways of doing so, because things are changing very quickly and we’re in a very dynamic landscape right now,” says Rajiv Mody, National Geographic’s vice president of social media. It’s not hard to see why Nat Geo, which launched its print magazine in 1888, hopped on board Discover: The company is a veteran of reinvention, and it’s lauded for its photography, a favorite in the Snapchat universe.

Most exciting is the experiment’s ability to allow social-media-hungry youth to bump into news. Fusion’s Kevin Roose wrote in February that Discover was racking up “millions of views per day, per publisher.”

But there are a few pitfalls. For one, critics have said certain channels focus more on strengthening the brand than quality reporting. And companies must make a compromise when they opt to host their content on Snapchat’s platform. While they control their channels, the setup keeps viewers from quickly jumping to their websites. So, they also have to split ad revenues.

Still, Discover seems to be a win-win for Snapchat and its media partners. And for Snapchat users, it’s just, well, easy. “You walk away from watching one of our editions and you really have a very comprehensive sense of six things that people are talking about today,” says Tony Maciulis, Yahoo Studios’ head of news. “We can do quality storytelling on other platforms by simply speaking to the audience there in the way that they’re accustomed to using that technology.”

What it needs to succeed: High-quality content and the continued attention of Snapchat users.

What might make it fail: Brand promotion dressed as news and the app’s easily overlooked button that takes users to Discover.

—Jack Murtha

This American Life‘s spin-off Serial

No spoilers here: Serial was the most talked about piece of journalism in 2014. The podcast, a This American Life spin-off, took a riveting look into the case of Adnan Syed, who is currently serving time for the murder of his former girlfriend, Hae-Min Lee. It smashed all sorts of records for podcasts—the latest download count, according to Serial’s producer Dana Chivvis, is a whopping 80 million. It became the type of cultural phenomenon usually reserved for hit television shows.

But Serial wasn’t just popular; it was a fine piece of journalism. Over the course of 12 episodes, it told the story of the murder, of Syed, of all the intrigues and mysteries surrounding the case, and told it week-by-week, like an old-time radio serial. While that is not new, it felt new because of the devotion to high journalistic quality.

“The medium feels more participatory because the person’s voice is in our ears,” said Katy Waldman, co-host of Slate’s Serial Spoiler Special, itself a popular podcast.

That was the most important part of the experiment. Host Sarah Koenig told the listener everything—all her reporting steps, her entire thought process. Serial was a combination of the reporter’s story and the character’s story; it’s something that journalism would be wise to do more often.

“The original idea for Serial was for us to produce the show as we were reporting it,” Chivvis said in an email. “Sometime during edits on episode two we realized that this meant Sarah’s investigation had to be part of the story too. And in fact, her reporting became a second structure that we weaved into the story.”

We may never know if Syed committed the crime, but we do know this: Serial’s success was a victory for thoughtful, investigative journalism, revealing that what’s old might really be new.

What it needs to succeed: Great, complicated, intriguing cases with lots of drama. Time and resources for reporting.

What might make it fail: Listeners getting tired of podcasts.

—Jeremy Fuchs

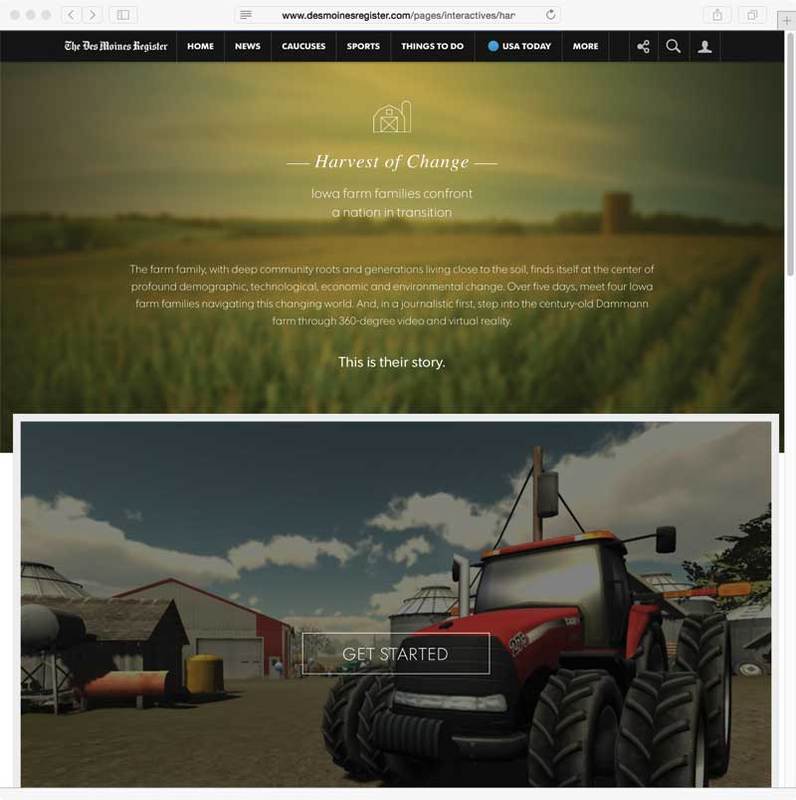

The Des Moines Register‘s virtual reality experiment

In late September, The Des Moines Register became one of the first newspapers in the world to try virtual reality.

The Iowa publication partnered with Gannett Digital (part of parent company Gannett) to create “Harvest of Change,” an immersive project that allows viewers to experience the economic and demographic change impacting Iowa’s farms. On the Oculus Rift virtual reality headset, or regular internet browsers, users navigate the sixth-generation Dammann family-owned farm, grappling with technology, genetically modified crops, and economic changes.

The project is a component of a print series divided into five categories: aging, culture, immigration, technology, and globalization.

Gannett elevated “Harvest of Change” into a virtual-reality experience by recreating the farm in a videogame-like world and incorporating 3D videos that users can find as they explore. The company also hired Total Cinema 360, a New York production company specializing in virtual reality.

This seems like an unexpected move, as the median age of the newspaper’s readers is 52, and many live in rural areas.

“We pride ourselves on being innovative at the Register, and it’s because of that reputation that Gannett Digital approached us about partnering on a virtual reality project,” said Amaile Nash, the paper’s executive editor and vice president for audience engagement. Nash also said the response has been massive, from national media to farmers.

The team behind “Harvest of Change” deserves a lot of credit for taking on virtual reality so early in the technology’s history. The graphics have the look and feel of a videogame, with blue floating icons that viewers can click to reveal videos, information and quotes from farmers. It’s still a novelty and the presentation is a great draw to get eyeballs on well-produced videos about serious topics like agriculture, something the media industry has long struggled to achieve.

Nuggets of information are, however, far and few between. Most of the time, users are maneuvering through a quiet farm with little character interaction. It can feel a little bland.

Virtual reality has yet to go mainstream. But if predictions from other technologists are correct, The Des Moines Register may be one of the pioneers.

What it needs to succeed: Oculus Rift in more households and desire for immersive experiences as a way to acquire news.

What might make it fail: Not enough integration of reporting and interactivity. Right now, users may be more preoccupied with the graphics, instead of being focused on the story.

—Alexandra Hoey

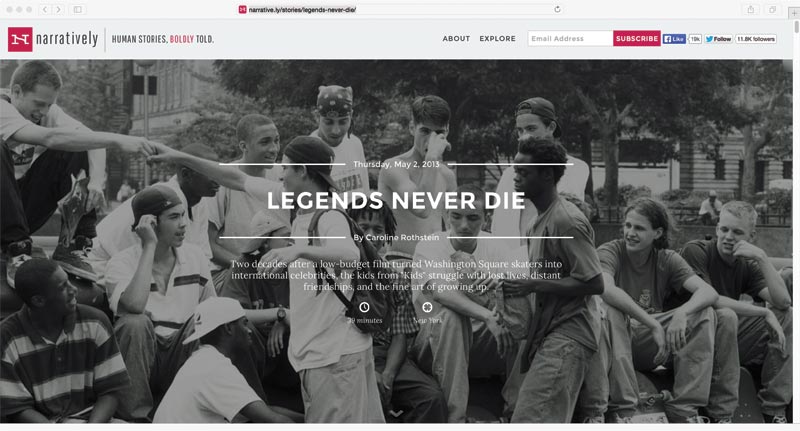

Narratively’s bet on longform

In the past, it was thought that publishing long stories was a feature of the print era, that digital readers were only looking for short, pithy posts. But that conventional wisdom has given way to a new sense that longform is actually well-suited to digital media—there are no space limitations, for starters. A number of sites have become home to such storytelling, and one of the most notable platforms is Narratively.

The site is experimental in its approach to delivering stories. It picks a different theme each week, publishing one in-depth story a day related to that theme.

The idea of Narratively, according to cofounder and editor Noah Rosenberg, is to “slow down the news cycle” and tell stories that aren’t being told elsewhere. Narratively’s tagline is, “Human stories, boldly told.”

Narratively doesn’t break news or run its stories under loud headlines. The site allows its 2,000 contributors to work on stories they wouldn’t necessarily be able to write for other publications, such as narrative-driven features or first-person essays. While the site does pay its contributors, rates can be meager, making it a good platform for passion projects or more creatively written stories about writers’ day-to-day work. Its features have taken readers to an abandoned coal town in Pennsylvania and illustrated “how a pimply Canadian farm boy rose to conquer the runways of Paris and Milan.”

“At Narratively, we can inject life into these projects that contributors have dedicated their time to, and in some cases a huge part of their careers to, but have never seen daylight,” Rosenberg says.

There is a relatively rigorous editorial process: Pitches are called for two to three months in advance, and two editors are assigned to each piece. Shirking the news cycle has been advantageous in this sense, as the site’s evergreen stories get more time for editing and its publication schedule can be rearranged.

One breakout story, “Legends Never Die” by Caroline Rothstein, chronicles the lives of the actors who starred in the 1995 cult film classic, Kids. Rothstein analyzed the impact the movie had on their lives, later producing a documentary on the same topic.

In 2012, Rosenberg led a Kickstarter campaign that raised nearly $54,000 to launch Narratively. But in order to create enough revenue to finance journalism, its contributors also produce branded content for various clients. The construct poses obvious questions regarding editorial independence. But thus far, Rosenberg says, there hasn’t been any overlap between contributors’ journalism and the branded content they produce for clients.

“We are very careful about which contributors are working on which creative products,” Rosenberg says. “We’ll never have a contributor working on two related things because we treat them as two very different parts of what we do.”

When a branded content project is big enough, editorial staff members are brought on to help. But the two types of work are typically separated.

“The big vision is as we grow we would love to have a separate division to work on that,” he adds.

It is, of course, difficult to ignore the fact that Narratively will soon have to answer the question faced by many other outlets—how to be both relevant and sustainable, and how to balance storytelling with branded content.

This is something Rosenberg and his team are fully aware of.

“The important thing is maintaining the editorial integrity, so we are careful about what branded content we produce,” said Rosenberg.

What it needs to succeed: Continuous supply of solid content.

What might make it fail: Short attention spans and the perception that marketing is affecting editorial content.

—Tariro Mzezewa

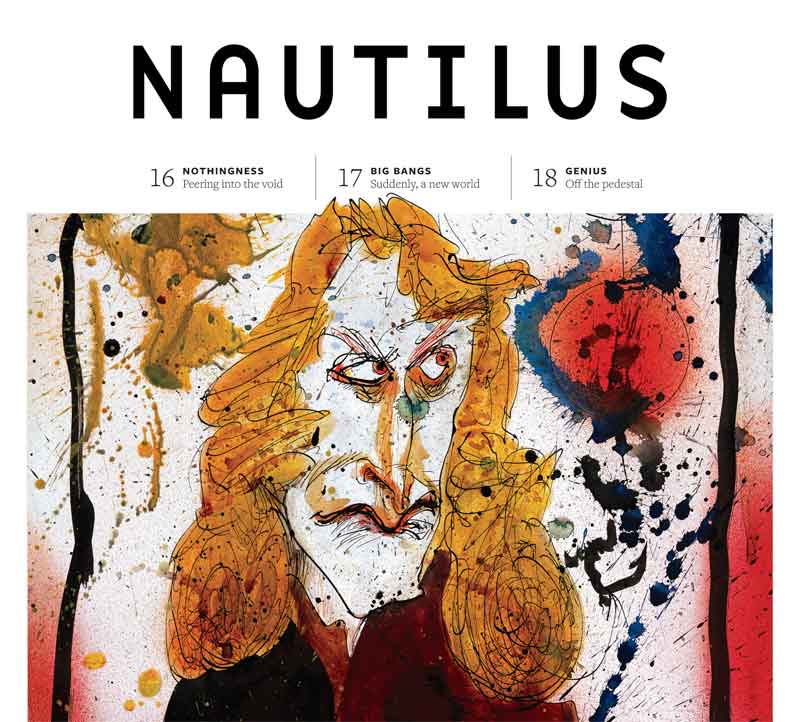

Nautilus‘ striking illustrations

How do you get children to read books that might otherwise seem unapproachable? Apparently, the well-known answer to that question can also be applied to a sophisticated science magazine like Nautilus: include captivating illustrations.

Launched in April 2013, Nautilus was conceived as a digital magazine (winning a 2015 National Magazine Award for its website in its first year of eligibility), but it quickly, and surprisingly, transitioned to print as well. The paper magazine has a striking design, immediately noticeable with original artwork on the front and back covers. For example, Ralph Steadman, who achieved fame for his work with Hunter S. Thompson, gave his signature touch to an illustration of Isaac Newton for the winter 2015 cover.

Novel as this approach may seem today, it draws on a model that was thought to be outdated.

“In the heyday of magazines decades ago, illustration really had a place of prominence,” explains Alissa Levin of Point Five Design, which touts Nautilus as one of its most accomplished clients. The abundance of stock material diminished demand for original artwork. “The design is very approachable and very intimate, even though the topic is really large, and I think readers crave intelligent, interesting writing.”

Although it was once more an anthology of web content, the print and online content will be more in sync as Nautilus shifts to a bimonthly schedule. Can it maintain this standard of design at that frequency? “Yes,” Levin says confidently. After all, its core product, the website, regularly features original illustration.

What it needs to succeed: Proven revenue model.

What might make it fail: More imitators may catch on to the effectiveness of a web-to-print model with strong supplementary illustrations.

—Danny Funt

Medium’s design simplicity

Blogging platforms have been around for a decade and a half, but the design of self-publishing platform Medium still stands out for its simplicity and style. If the enemy of cleanliness is clutter, then Medium’s new ornaments for posts—embedded videos, pullout quotations, audio buttons—could have risked undermining its aesthetic. Yet these additions have demonstrated that a clean layout need not be dry.

The three-year-old website, created by two co-founders of Twitter, has attracted a mix of high-end and everyman writers. While these ways of supplementing essays are not unique to Medium, it’s striking how scarcely they’re seen on traditional news websites. Two tools in particular fit this bill: embedded audio to accompany quotes, and commenting options for individual paragraphs. Both are unobtrusive inclusions that ought to become commonplace.

The metric that matters most to Medium is how long a visitor spends reading a given article. The website measures that time for each story; according to a post by the company, it believes “there are no average users, and there are no average posts.” Instead, this metric, combined with Medium’s algorithms that match users with content they’re likely to enjoy, is designed to foster great content.

The Medium model is based on quality writing, rather than nonstop, half-hearted posts. It’s not kind to search engine optimization or clickbait. With its clean, easy-to-use publishing tools, that might explain the website’s success in the world of professional and amateur writers alike. Even the late, great David Carr used Medium as the stage for his Boston University students’ work.

Like Twitter, Medium prides itself on being a stripped-down platform for communication—stripped of obstacles, though not embellishments.

What it needs to succeed: Ensuring add-ons stay useful without becoming excessive or over-complicated.

What might make it fail: The next big self-publishing platform.

—Danny Funt

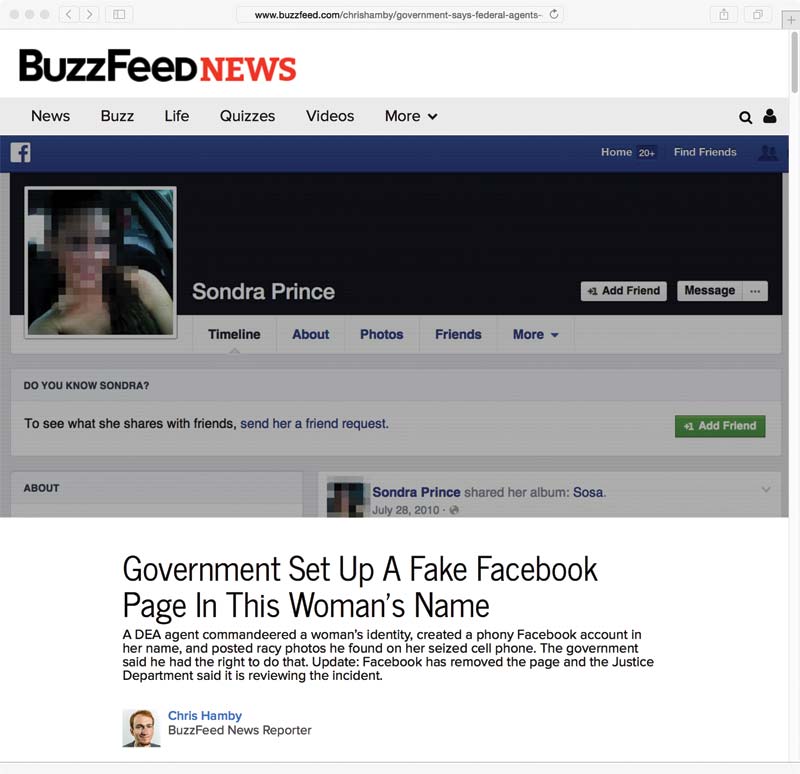

Buzzfeed’s business model

Buzzfeed was once only a phenomenally popular entertainment website that excelled in creating viral content for the social web, using lists, quizzes, and gifs to reach an audience that skewed toward young smartphone users. Then, with a huge following and growing cash flow, it decided it also wanted to be a serious news player in hard news.

That’s what sets apart BuzzFeed from many other digital media startups—it doesn’t need its news division to draw a large share of its audience. BuzzFeed’s business model—the company generated more than $100 million in revenue last year—is based on sponsored content produced by its own creative staff. Separate from the editorial staff, those workers employ the company’s social web know-how to bring brands to millions of internet users.

But whether BuzzFeed can build and maintain a coherent brand remains an open debate. Can the company balance “What Colors Are This Dress?” (a viral mega-hit) with “At Least Eight Killed After Gunmen Attack Somali Education Ministry” (hard news)? More importantly, can the latter coexist with “How Would You Die In ‘Mortal Kombat’?” (sponsored content)? For now, native ads do not appear in the News section of the site. Will it manage to keep News and Entertainment attractive to the same group of readers? What’s more, is BuzzFeed News competing with The New York Times, or is it a source of news for young people who seem almost allergic to legacy media?

This is not clear yet. On one hand, it has managed to grab a string of top talent from the Timeses and Posts of the world, who are writing well-reported articles on topics ranging from women affiliated with or affected by ISIS to the changing global market for Apple products to the ins and outs of the 2016 presidential campaign. But it’s also experimenting with delivery formats tailored to the contemporary social-mobile news consumer. Two examples are the recently launched BuzzFeed News newsletter, aimed at people who are “not necessarily news junkies,” as reporter Millie Tran wrote in a blog post; and the highly anticipated BuzzFeed News app, expected to launch this summer for iOS. The creation of an app is the latest sign that BuzzFeed News is attempting to separate its brand identity from that of the BuzzFeed mothership.

We still hear industry people saying, “BuzzFeed is not journalism.” Maybe they are the same people who claim Nespresso is not coffee.

What it needs to succeed: Entice a significant portion of its 220 million unique visitors a month to read BuzzFeed News.

What might make it fail: Not reaching sustaniable profitability—or losing credibility along the way.

—André Tassinari

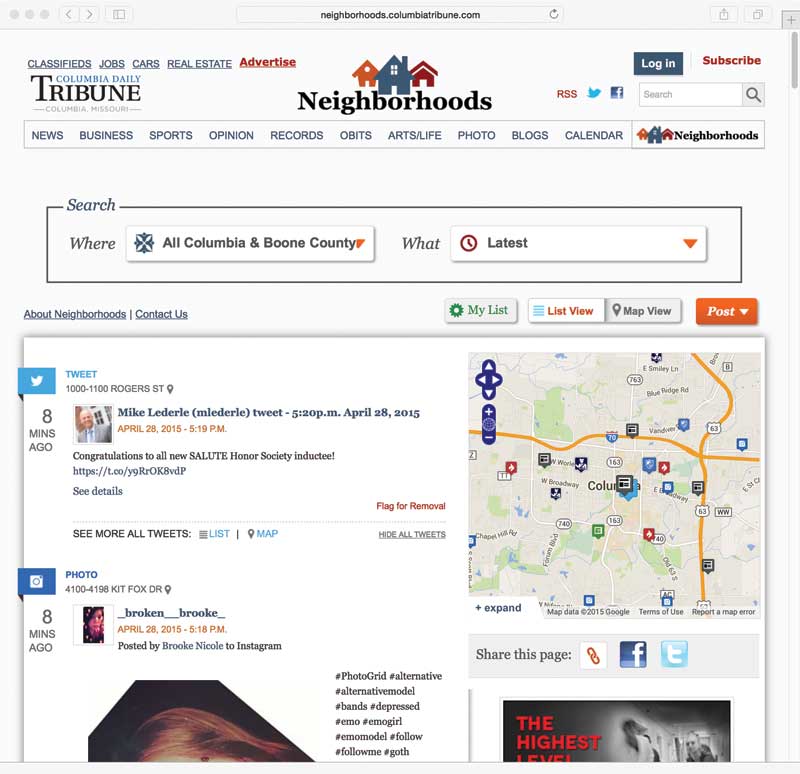

Columbia Daily Tribune‘s Neighborhoods

Online hyperlocal news? In a post-patch era, that’s not so experimental anymore. But in Missouri, the Columbia Daily Tribune has merged local and data journalism to create a tool that seems more like the product of a digital startup than a newspaper.

“Neighborhoods” is an online platform that shows all sorts of incidents, events, and public information on a map, down to the street level. Users can search geographically by neighborhood, school district, ward, zip code, or address. They can also scan for specific types of data, including police and fire activity, restaurant inspections, social-media posts, and Tribune news stories.

“You can really focus on your neighborhood where you live and see what kind of news is happening around you that really wasn’t easily accessible before—at least not presented in that kind of way,” says Andy Waters, the newspaper’s president and general manager.

The concept of Neighborhoods began more than five years ago, with the idea to place police incidents on a map. By the time it came online in March 2014, that vision had expanded to include just about any public data or geotagged social-media posts the Tribune could get its hands on. It took off quickly, with a couple thousand monthly uniques, and now draws 9,000 unique visitors each month. The growth, however modest, is encouraging for a hyperlocal news project of this caliber.

One of the project’s biggest goals was to bring more transparency to local government. Waters says that was tough at first, because public entities didn’t think the newspaper’s requests for real-time information fit the Sunshine Law. The Tribune ultimately succeeded, for the most part. Even if Neighborhoods failed, bringing to light these outdated and inaccessible public-records systems would have been a major plus for journalism.

Neighborhoods is a killer idea that has the chance to unite and inform Boone County residents. In just a couple of clicks, they can check out new businesses that are opening down the block or where to visit an open house. “It definitely stretches the definition of news,” says Waters. And that’s okay. This all-inclusive community map has the power to become a model for hyperlocal news across the country.

Right now, there’s not a lot of user-posted content on the site, though. That level of engagement needs to change. The Tribune is also in the process of figuring out how to monetize the audience it built through Neighborhoods—an all-too-important challenge that’s become all too familiar for local news.

What it needs to succeed: Monetization.

What might make it fail: Lack of user engagement and sealed public records.

—Jack Murtha

theSkimm’s news innovation

The email newsletter is back, and theSkimm is leading the way on this throwback to the internet’s early days.

theSkimm’s logo is an idealized version of its female, millennial reader—a busy, successful woman who is still staying abreast of all goings-on. She’s a skirted silhouette accessorized with pearls, pumps and perfect updo, tablet in hand. Each daily newsletter has a conversational tone that feeds subscribers the news of the day in bite-size chunks.

Like BuzzFeed, theSkimm finds an audience in a high-low, omnivorous approach to news: Topics tackled range from complicated geopolitical issues to fashion-business news. The “Skimm’d” perspective breaks down top headlines, answers a few questions, and explains each issue’s importance. Readers learn what they need to know and why they need to know it.

The newsletter’s cheeky tone extends from the subject line all the way down to the happy birthday shout-outs to readers (like Politico’s Playbook newsletter). Think of the newsletter as a morning show delivered straight to your inbox.

And like BuzzFeed, theSkimm has been incredibly successful with this approach, with reports pegging the number of subscribers at more than 1 million. This experiment has drawn the attention of tastemakers like Oprah Winfrey and Sarah Jessica Parker, and founders Danielle Weisberg and Carly Zakin landed on this year’s Forbes’ 30 Under 30 Media list. Investors have also taken note: The pair, who quit nbc News to start their business, netted $6.25 million in financing last year. Not bad for a media business whose only form of content is a daily email.

What it needs to succeed: Time will tell if the startup becomes profitable, but continuing to grow its million-plus reader base should be the top priority.

What might make it fail: theSkimm’s hallmark sauciness can sometimes veer too far toward flippant.

—Kay Nguyen

The Editors are the staffers of the Columbia Journalism Review.