Sign up for The Media Today, CJR’s daily newsletter.

The best culture writers move beyond a piece of art or entertainment to examine larger trends—the power of Michelle Obama’s image, the fetishization of the “cool girl,” the oversexualization of the black male body. They use a cultural moment—an awards ceremony, a new Netflix miniseries, an album release—to discuss what it really means to be human.

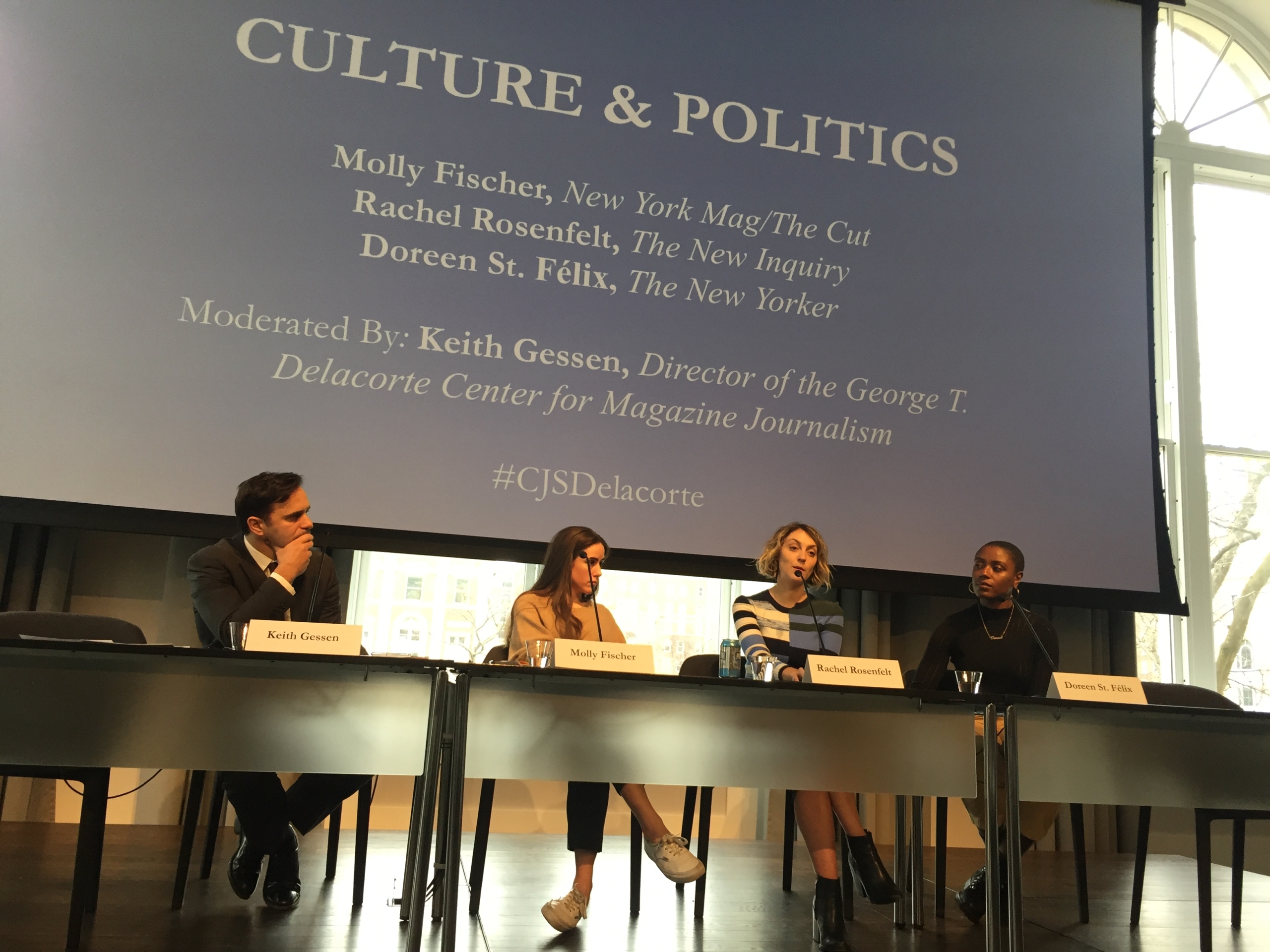

Today, what it means to be human in America has a lot to do with the experience of living under Trump. But that doesn’t mean the culture beat must be dominated by coverage of him. This was just one of the topics at a half-day conference on the intersection of politics and magazines on Friday, organized by the George T. Delacorte Center for Magazine Journalism at Columbia’s Graduate School of Journalism. The panel, “The Culture Front,” dove deep into the effect of Trump—as well as movements like #MeToo—on cultural criticism with Molly Fischer, features editor New York magazine’s The Cut; Rachel Rosenfelt, founding editor of The New Inquiry and now publisher of The New Republic; Doreen St. Félix, staff writer at The New Yorker; and moderator Keith Gessen, Columbia’s Delacorte professor of magazine journalism and a founding editor of n+1 magazine.

Trending: From Russia to flyover country, Sarah Kendzior might be the voice we need

Even in the culture beat, there’s pressure to Trumpify everything—to make connections between his presidency and whatever you’re covering, according to St. Félix. Trump has become the center of gravity. There’s a tendency to “stretch [the story] in order for it, like saran wrap, to fit what people want,” she says. When she sits down to write, St. Félix pushes back on that urge and asks herself, “What is the irreducible truth? What is the actual way these two things are interacting?” She applies that framework to everything she drafts, like her piece on Eminem’s freestyle response to Trump’s rise. The Trump connection is obvious—Eminem’s single, “The Storm,” was a clear takedown of the president. But St. Félix doesn’t simplify the relationship between the performer and subject. Instead, she imbues her piece with greater context, specifically the rapper’s historical and present-day influence on the “angry white man.” “His immersion in black Detroit, and, as he grew increasingly famous, his association with black men—Dr. Dre, 50 Cent, and the group he mentored, D12—dredged traditional fears to the surface. He was a vicious interlocutor, a disruptor of modern whiteness,” she writes.

For The Cut, New York’s women’s vertical, Trump’s election spurred an internal diagnostic of how it could, and would, continue to serve its readers under the presidency of a man accused of sexual assault and harassment. They settled on a nuanced, empathetic approach to the 24-hour news cycle, with an emphasis on smart and thoughtful commentary rather than “hot takes.” That approach has come into its own with #MeToo, both of which, says Fischer, are a result of Trump’s White House.

The Cut’s response to Trump and #MeToo is working. Its website now reaches 8 million monthly unique visitors—up more than 40 percent since 2016. That’s a caveat of things getting “bad,” says Fischer. “When things are terrible, they are good for for us. People look to us [women’s sites] to talk about it.” At this moment, outlets like The Cut are at the forefront of the conversation. That’s embodied by voices like Rebecca Traister, whose essays and reported features not only drive clicks and retweets, but also push forward critical conversations about identity politics, gender and the workplace, and female rage. It’s become a place where journalists like Suki Kim, who reported on sexual harassment at WNYC, and Moira Donegan, the creator of the now-infamous “Shitty Media Men” list, take their stories.

RELATED: Through radical empathy, New York‘s The Cut achieves success in the women’s media space

When Trump was elected, The New Inquiry was undergoing its own changes. The online magazine re-launched in November 2016 with a new look and senior staff, says Rosenfelt. But post-Trump, its biggest shift came in the form of technological innovation. Known for its cultural and literary criticism, The New Inquiry pivoted to software with a program called Bail Bloc, which launched late last year. The app taps into your computer’s unused power to mine cryptocurrency and then redirects those funds to make bail payments for defendants in US courts. Rosenfelt calls it “rhetorical software,” exposing “the way cryptocurrency works by flipping the way it works.”

The project stems from the “critical mass of people with specialized expertise that want to do something, but don’t want to be in those gigantic firms,” says Rosenfelt. She noticed a growing number of millennial technologists wanting to contribute to the post-Trump discourse, and Bail Bloc was a way to do just that. “It isn’t any harder than putting together an issue of the magazine,” she jokes.

Trump has become an instrument for journalists on the culture front. Now they’re grappling with how to best put that instrument to use—whether that means building an app, or rethinking their approach to writing.

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.